Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Problems of the Biliary System and Pancreas

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

7 Identify risk factors for gallbladder disease.

8 Interpret diagnostic test results associated with gallbladder disease.

10 Compare and contrast the pathophysiology of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

11 Interpret laboratory test results associated with acute pancreatitis.

12 Interpret common assessment findings associated with acute and chronic pancreatitis.

13 Prioritize nursing care for patients with acute pancreatitis and patients with chronic pancreatitis.

14 Explain the use and precautions associated with enzyme replacement for chronic pancreatitis.

15 Develop a postoperative plan of care for patients having a Whipple procedure.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy; Gallbladder Removal

Answers for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The biliary system (liver and gallbladder) and pancreas secrete enzymes and other substances that promote food digestion in the stomach and small intestine. When these organs do not work properly, the person has impaired digestion, which may result in inadequate nutrition. Collaborative care for patients with problems of the biliary system and pancreas includes the need to promote nutrition for healthy cellular function. This chapter focuses on problems of the gallbladder and pancreas. Liver disorders were described in Chapter 61.

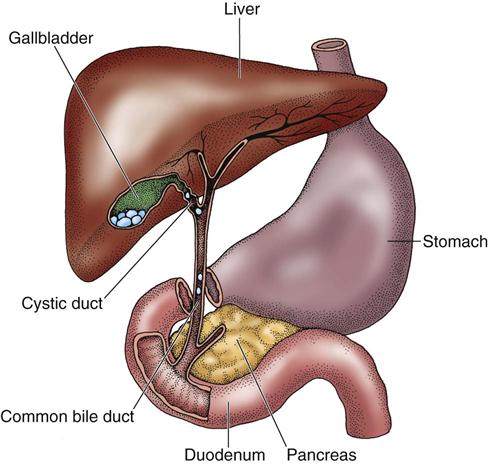

Because of the close anatomic location of these organs, disorders of the gallbladder and pancreas may extend to other organs if the primary health problem is not treated early. Inflammation is caused by obstruction (blockage) in the biliary system from gallstones, edema, stricture, or tumors. For example, gallstones in the cystic duct cause cholecystitis. Gallstones lodged in the ampulla of Vater block the flow of bile and pancreatic secretions, which can result in pancreatitis.

Gallbladder Disorders

Cholecystitis

Pathophysiology

Cholecystitis is an inflammation of the gallbladder that affects many people, most commonly in affluent countries. It may be either acute or chronic, although most patients have the acute type. Over 500,000 surgeries for this health problem are done in the United States each year (Comstock, 2008).

Acute Cholecystitis

Two types of acute cholecystitis can occur: calculous and acalculous cholecystitis. The most common type is calculous cholecystitis, in which chemical irritation and inflammation result from gallstones (cholelithiasis) that obstruct the cystic duct (most often), gallbladder neck, or common bile duct (choledocholithiasis) (Fig. 62-1). When the gallbladder is inflamed, trapped bile is reabsorbed and acts as a chemical irritant to the gallbladder wall; that is, the bile has a toxic effect. Reabsorbed bile, in combination with impaired circulation, edema, and distention of the gallbladder, causes ischemia and infection. The result is tissue sloughing with necrosis and gangrene. The gallbladder wall may eventually perforate (rupture). If the perforation is small and localized, an abscess may form. Peritonitis, infection of the peritoneum, may result if the perforation is large.

The exact pathophysiology of gallstone formation is not clearly understood, but abnormal metabolism of cholesterol and bile salts plays an important role in their formation. The gallbladder provides an excellent environment for the production of stones because it only occasionally mixes its normally abundant mucus with its highly viscous, concentrated bile. Impaired gallbladder motility can lead to stone formation by delaying bile emptying and causing biliary stasis.

Gallstones are composed of substances normally found in bile, such as cholesterol, bilirubin, bile salts, calcium, and various proteins. They are classified as either cholesterol stones or pigment stones. Cholesterol calculi form as a result of metabolic imbalances of cholesterol and bile salts. They are the most common type found in people in the United States. Pigmented stones are associated with cirrhosis of the liver (McCance et al., 2010).

Bacteria can collect around the stones in the biliary system. Severe bacterial invasion can lead to life-threatening suppurative cholangitis when symptoms are not recognized quickly and pus accumulates in the ductal system.

Acalculous cholecystitis (inflammation occurring without gallstones) is typically associated with biliary stasis caused by any condition that affects the regular filling or emptying of the gallbladder. For example, a decrease in blood flow to the gallbladder or anatomic problems such as twisting or kinking of the gallbladder neck or cystic duct can result in pancreatic enzyme reflux into the gallbladder, causing inflammation. Most cases of this type of cholecystitis occur in patients with:

Chronic Cholecystitis

Chronic cholecystitis results when repeated episodes of cystic duct obstruction cause chronic inflammation. Calculi are almost always present. In chronic cholecystitis, the gallbladder becomes fibrotic and contracted, which results in decreased motility and deficient absorption.

Pancreatitis and cholangitis (bile duct inflammation) can occur as chronic complications of cholecystitis. These problems result from the backup of bile throughout the biliary tract. Bile obstruction leads to jaundice.

Jaundice (yellow discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes) and icterus (yellow discoloration of the sclerae) can occur in patients with acute cholecystitis but are most commonly seen in those with the chronic form of the disease. Obstructed bile flow caused by edema of the ducts or gallstones contributes to extrahepatic obstructive jaundice. Jaundice in cholecystitis may also be caused by direct liver involvement. Inflammation of the liver’s bile channels or bile ducts may cause intrahepatic obstructive jaundice, resulting in an increase in circulating levels of bilirubin, the major pigment of bile.

When the concentration of bilirubin in the blood increases, jaundice can occur. In a person with obstructive jaundice, the normal flow of bile into the duodenum is blocked, allowing excessive bile salts to accumulate in the skin. This accumulation of bile salts leads to pruritus (itching) or a burning sensation. The bile flow blockage also prevents bilirubin from reaching the large intestine, where it is converted to urobilinogen. Because urobilinogen accounts for the normal brown color of feces, clay-colored stools result. Water-soluble bilirubin is normally excreted by the kidneys in the urine. When an excess of circulating bilirubin occurs, the urine becomes dark and foamy because of the kidneys’ effort to clear the bilirubin.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

A familial or genetic tendency appears to play a role in the development of cholelithiasis, but this may be partially related to familial nutrition habits (excessive dietary cholesterol intake) and sedentary lifestyles. Genetic-environment interactions may contribute to gallstone production (Attasaranya et al., 2008).

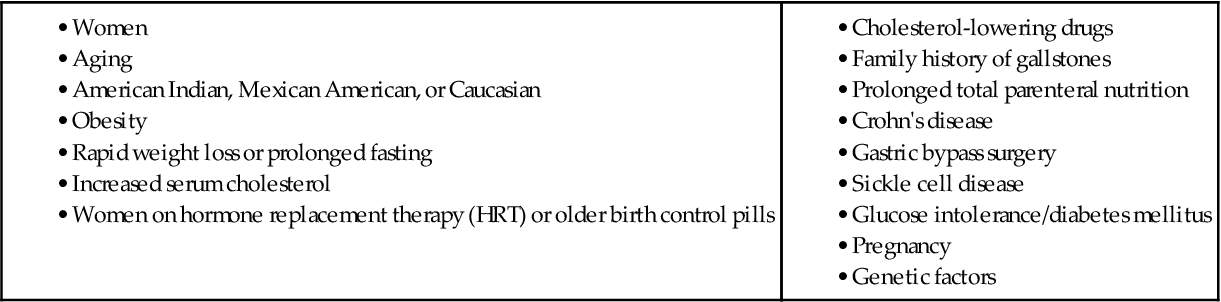

Cholelithiasis is seen more frequently in obese patients, probably as a result of impaired fat metabolism or increased cholesterol. The risk for developing gallstones increases as people age. Patients with diabetes mellitus are also at increased risk because they usually have higher levels of fatty acids (triglycerides). American Indians have a higher incidence of the disease than other groups, which may be due to the higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and obesity in this population (McCance et al., 2010). Risk factors for cholecystitis are listed in Table 62-1.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Patients with acute cholecystitis present with abdominal pain, although clinical manifestations vary in intensity and frequency (Chart 62-1).

Obtain the patient’s height, weight, and vital signs, or delegate these activities to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). Ask about food preferences, and determine whether excessive fat and cholesterol are part of the diet. Inquire if any foods cause pain. Question whether any GI symptoms occur when fatty food is eaten: flatulence (gas), dyspepsia (indigestion), eructation (belching), anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain or discomfort.

Ask the patient to describe the pain, including its intensity and duration, precipitating factors, and any measures that relieve it. Pain may be described as indigestion of varying intensity, ranging from a mild, persistent ache to a steady, constant pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant. It may radiate to the right shoulder or scapula. In some cases, the abdominal pain of chronic cholecystitis may be vague and nonspecific. The usual pattern is episodic. Patients often refer to acute pain episodes as “gallbladder attacks.”

The severe pain of biliary colic is produced by obstruction of the cystic duct of the gallbladder or movement of one or more stones. When a stone is moving through or is lodged within the duct, tissue spasm occurs in an effort to get the stone through the small duct.

Ask patients to describe their daily activity or exercise routines to determine whether they are sedentary. Question whether there is a family history of gallbladder disease. If the patient is female, ask whether she takes hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or birth control pills.

Assessment for rebound tenderness (Blumberg’s sign) and deep palpation are performed only by physicians and advanced practice nurses. To elicit rebound tenderness, the health care provider pushes his or her fingers deeply and steadily into the patient’s abdomen and then quickly releases the pressure. Pain that results from the rebound of the palpated tissue may indicate peritoneal inflammation. Deep palpation below the liver border in the right upper quadrant may reveal a sausage-shaped mass, representing the distended, inflamed gallbladder. Percussion over the posterior rib cage worsens localized abdominal pain.

In chronic cholecystitis, patients may have slowly developing symptoms and may not seek medical treatment until late symptoms such as jaundice (yellowing of the skin), clay-colored stools, and dark urine occur from biliary obstruction. Yellowing of the sclerae (icterus) and oral mucous membranes may also be present. Steatorrhea (fatty stools) occurs because fat absorption is decreased because of the lack of bile. Bile is needed for the absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins in the intestine. As with any inflammatory process, the patient may have an elevated temperature of 99° to 102° F (37.2° to 38.9° C), tachycardia, and dehydration from fever and vomiting.

Diagnostic Assessment

A differential diagnosis rules out other diseases that may cause similar symptoms, such as peptic ulcer disease, hepatitis, and pancreatitis. An increased white blood cell (WBC) count indicates inflammation. Serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may be elevated, indicating abnormalities in liver function in patients with severe biliary obstruction. The direct (conjugated) and indirect (unconjugated) serum bilirubin levels are also elevated. If the pancreas is involved, serum amylase and lipase levels are elevated.

Calcified gallstones are easily viewed on abdominal x-ray. Stones that are not calcified cannot be seen. Ultrasonography (US) of the right upper quadrant is the best diagnostic test for cholecystitis. It is safe, accurate, and painless. Acute cholecystitis is seen as edema of the gallbladder wall and pericholecystic fluid. A hepatobiliary scan can be performed to visualize the gallbladder and determine patency of the biliary system.

When the cause of cholecystitis or cholelithiasis is not known or the patient has manifestations of biliary obstruction (e.g., jaundice), an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed. Some patients have the less invasive and safer magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can be performed by an interventional radiologist. For this procedure, the patient is given oral or IV contrast material (gadolinium) before having a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Daniak et al., 2008). Before the test, ask the patient about any history of urticaria (hives) or other allergy. Gadolinium does not contain iodine, which decreases the risk for an allergic response. Chapter 55 discusses these tests in more detail.

Interventions

Most patients do not respond to nonsurgical interventions during the acute phase of cholecystitis. Surgery is the treatment of choice.

Nonsurgical Management

Many people with gallstones have no symptoms. Acute pain occurs when gallstones partially or totally obstruct the cystic or common bile duct. Most patients find that they need to avoid fatty foods to prevent further episodes of biliary colic. Withhold food and fluids if nausea and vomiting occur. IV therapy is used for hydration.

Acute biliary pain requires opioid analgesia, such as morphine or hydromorphone (Dilaudid). In the past, meperidine (Demerol) was the drug of choice because it was thought to cause fewer spasms of the sphincter of Oddi, which blocks bile flow. However, this drug breaks down into a toxic metabolite (normeperidine) and can cause seizures, especially in older adults. All opioids may cause some degree of sphincter spasm.

Ketorolac (Toradol, Acular) may be used for mild to moderate pain. The health care provider prescribes antiemetics to control nausea and vomiting. IV antibiotic therapy may also be given, depending on the cause of cholecystitis or as a one-time dose for surgery.

For some patients with small stones or for those who are not good surgical candidates, a treatment that is commonly used for kidney stones can be used to break up gallstones—extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). This procedure can be used only for patients who have a normal weight, cholesterol-based stones, and good gallbladder function. The patient lies on a water-filled pad, and shock waves break up the large stones into smaller ones that can be passed through the digestive system. During the procedure, he or she may have pain from the movement of the stones or duct or gallbladder spasms. A therapeutic bile acid, such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), may be used after the procedure to help dissolve the remaining stone fragments.

Another treatment option in people who cannot have surgery is the insertion of a percutaneous transhepatic biliary catheter to open the blocked duct(s) so that bile can flow. Catheters can be placed several ways, depending on the condition of the biliary ducts, in an internal, external, or internal/external drain. Biliary catheters usually divert bile from the liver into the duodenum to bypass a stricture. When all of the bile enters the duodenum, it is called an internal drain. However, in some cases, a patient has an internal/external drain in which part of the bile empties into a drainage bag. Patients who need this drain for an extended period may have the external drain capped. If jaundice or leakage around the catheter site occurs, teach the patient to reconnect the catheter to a drainage bag and have a follow-up cholangiogram injection done by an interventional radiologist. An external only catheter is connected either temporarily or permanently to a drainage bag. A reduction in bile drainage indicates that the drain is no longer working.

Surgical Management

Cholecystectomy is a surgical removal of the gallbladder. One of two procedures is performed: the laparoscopic cholecystectomy and, far less often, the traditional open approach cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a minimally invasive surgery (MIS), is currently the “gold standard” and is performed far more often than the traditional open approach. The advantages of MIS include:

The laparoscopic procedure (often called a “lap chole”) is commonly done on an ambulatory care basis in a same-day surgery suite. The surgeon explains the procedure. The nurse answers questions and reinforces the physician’s instructions. Reinforce what to expect after surgery, and review pain management, deep-breathing exercises, and incentive spirometry use. There is no special preoperative preparation other than the routine preparation for surgery under general anesthesia described in Chapter 16. An IV antibiotic is usually given immediately before or during surgery.

During the surgery, the surgeon makes a very small midline puncture at the umbilicus. Additional small incisions may be needed, although single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) using a flexible endoscope can be done (Binenbaum et al., 2009). The abdominal cavity is insufflated with 3 to 4 L of carbon dioxide. Gasless laparoscopic cholecystectomy using abdominal wall lifting devices is a more recent innovation in some centers. This technique results in improved pulmonary and cardiac function. A trocar catheter is inserted, through which a laparoscope is introduced. The laparoscope is attached to a video camera, and the abdominal organs are viewed on a monitor. The gallbladder is dissected from the liver bed, and the cystic artery and duct are closed. The surgeon aspirates the bile and crushes any large stones and then extracts the gallbladder through the umbilical port.

Removing the gallbladder with the laparoscopic technique reduces the risk for wound complications. Some patients have discomfort from carbon dioxide retention in the abdomen.

The patient is usually discharged from the hospital or surgery center the same day, although older and obese patients may stay overnight. Provide postoperative teaching regarding pain management, incision care, and follow-up appointments. After laparoscopic surgery, the patient can return to usual activities much sooner than those having an open cholecystectomy. Most patients are able to resume usual activities within a week.

A newer procedure is natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for removal of or repair of organs. Surgery can be performed on many body organs through the mouth, vagina, and rectum. For removal of the gallbladder, the vagina is used most often in women because it can be easily decontaminated with Betadine or other antiseptic and allows easy access into the peritoneal cavity. The surgeon makes a small internal incision through the cul-de-sac of Douglas between the rectum and uterine wall to access the gallbladder. The main advantages of this procedure are the lack of visible incisions and minimal, if any, postoperative complications (Navarra et al., 2010).

Traditional Cholecystectomy.

Use of the open surgical approach (abdominal laparotomy) has greatly declined during the past 20 years. Patients who have this type of surgery usually have severe biliary obstruction.

The surgical nurse provides the usual preoperative care and teaching in the operating suite on the day of surgery (see Chapter 16). The surgeon removes the gallbladder through an incision and explores the biliary ducts for the presence of stones or other cause of obstruction. If the common bile duct is explored, the surgeon may insert a T-tube drain to ensure patency of the duct, although this is not done commonly today. Trauma to the common bile duct stimulates inflammation, which can slow bile flow and contribute to bile stasis. In addition, the surgeon usually inserts a drainage tube such as a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain. This tube is placed in the gallbladder bed to prevent fluid accumulation. The drainage is usually serosanguineous (serous fluid mixed with blood) and is stained with bile in the first 24 hours after surgery. Antibiotic therapy is given to prevent infection.

Patient care for a patient who has had a traditional open cholecystectomy is similar to the care for any patient who has had abdominal surgery under general anesthesia as described in Chapter 18. Postoperative incisional pain after a traditional cholecystectomy is controlled with opioids using a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. Encourage the patient to use coughing and deep-breathing exercises when pain is controlled and the incision is splinted.

Antiemetics may be necessary for episodes of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Administer the antiemetic early, as prescribed, to prevent retching associated with vomiting and thus to decrease pain related to muscle straining.

Provide care for the incision, the surgical drain, and possibly a T-tube to drain bile into a drainage bag via gravity flow. The surgeon typically removes the surgical dressing and drain within 24 hours after surgery.

The patient is NPO until fully awake postoperatively. Document the patient’s level of consciousness, vital signs, and pain level. Assess the surgical incision for signs of infection, such as excessive redness or purulent drainage. Report changes to the surgeon immediately. Begin ambulation as soon as possible to prevent deep vein thrombosis and promote peristalsis.

Advance the diet from clear liquids to solid foods as peristalsis returns. The patient usually resumes solid foods and is discharged to home 1 to 2 days after surgery, depending on any complications and the patient’s general condition. In the early postoperative period, if bile flow is reduced, a low-fat diet may reduce discomfort and prevent nausea. For most patients, a special diet is not required. Advise them to eat nutritious meals and avoid excessive intake of fatty foods, especially fried food, butter, and “fast food.” If the patient is obese, recommend a weight-reduction program, such as Weight Watchers.

Teach the patient to keep the incision clean and report any changes that may indicate infection. Remind him or her to report repeat abdominal or epigastric pain with vomiting that may occur several weeks to months after surgery. These symptoms indicate possible postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS).

Although PCS occurs in a small number of patients, patients who have it are usually discouraged that they have pain after already having surgery to cure it (Comstock, 2008). Causes of PCS are listed in Table 62-2. Management depends on the exact cause but usually involves the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to find the cause of the problem and repair it. This procedure and related nursing care are described in Chapter 55. Collaborative care includes pain management, antibiotics, nutrition and hydration therapy (possibly short-term parenteral nutrition), and control of nausea and vomiting.

Cancer Of The Gallbladder

Pathophysiology

Primary cancer of the gallbladder is rare and is more common in women than in men. Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer of the gallbladder account for the majority of the cases. The tumor tends to begin in the inner layer (mucosa) of the gallbladder wall. It then grows outward to include the entire gallbladder before it begins to metastasize (spread) to close organs like the liver, small intestine, and pancreas. These rare cancers appear more frequently in patients with pre-existing chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. They also tend to occur more often in American Indians than in any other group, but the reason for this finding is not known (McCance et al., 2010).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Early symptoms, when present, develop slowly and are similar to those of chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. Assess for characteristic manifestations, which include:

A moderately tender, irregularly shaped mass may be palpated. Gallbladder cancer is typically discovered during other procedures for diagnosis of suspected cholecystitis or during cholecystectomy.

The diagnosis of gallbladder cancer is usually made by ultrasonography, but other tests can be done. Some patients have a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in which a contrast medium is injected into the bile ducts. Other more invasive tests, like endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), may be performed. Liver function studies indicate liver involvement. Two serum tests that reveal the presence of cancer cells are carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay and CA 19-9.

Interventions

The prognosis for the patient with cancer of the gallbladder is poor because it is usually diagnosed in late disease due to the lack of specific manifestations. Three treatments are used: surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Surgical intervention is either potentially curative (for an early resectable tumor) or palliative (for advanced disease with metastasis). The patient who is diagnosed with early disease has either a simple cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) or extended cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder, surrounding lymph nodes, and a small margin of the liver). For palliative surgery to extend the patient’s life or decrease discomfort, radical surgery is done.

Nursing care is similar to that for patients who have a cholecystectomy (see p. 1319) or Whipple procedure (see p. 1331), depending on the extent of disease. These procedures are described elsewhere in this chapter. Teach terminally ill patients and their families about end-of-life care and available hospice services (see Chapter 9).

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy alone are not effective for gallbladder cancer. However, they may be given as adjunctive procedures with surgery or instead of surgery in patients who are not surgical candidates to shrink the tumor. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy that is much more advanced and intense than regular radiation is used. Chemotherapy with 5-fluorourical (5-FU), doxorubicin, and mitomycin may be effective in reducing tumor size. Chapter 24 describes in detail the care of the patient receiving radiation and chemotherapy.

Pancreatic Disorders

Acute Pancreatitis

Pathophysiology

Acute pancreatitis is a serious and, at times, life-threatening inflammatory process of the pancreas. This process is caused by a premature activation of excessive pancreatic enzymes that destroy ductal tissue and pancreatic cells, resulting in autodigestion and fibrosis of the pancreas. The pathologic changes occur in different degrees. The severity of pancreatitis depends on the extent of inflammation and tissue damage. Pancreatitis can range from mild involvement evidenced by edema and inflammation to necrotizing hemorrhagic pancreatitis (NHP). NHP is diffusely bleeding pancreatic tissue with fibrosis and tissue death.

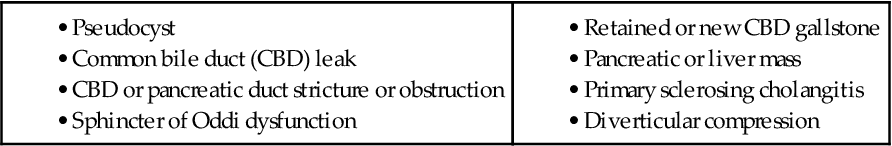

The pancreas is unusual in that it functions as both an exocrine gland and an endocrine gland. The primary endocrine disorder is diabetes mellitus and is discussed in Chapter 67. The exocrine function of the pancreas is responsible for secreting enzymes that assist in the breakdown of starches, proteins, and fats. These enzymes are normally secreted in the inactive form and become activated once they enter the small intestine. Early activation (i.e., activation within the pancreas rather than the intestinal lumen) results in the inflammatory process of pancreatitis. Direct toxic injury to the pancreatic cells and the production and release of pancreatic enzymes (e.g., trypsin, lipase, elastase) result from the obstructive damage. After pancreatic duct obstruction, increased pressure may contribute to ductal rupture allowing spillage of trypsin and other enzymes into the pancreatic parenchymal tissue. Autodigestion of the pancreas occurs as a result (Fig. 62-2). In acute pancreatitis, four major pathophysiologic processes occur: lipolysis, proteolysis, necrosis of blood vessels, and inflammation.

The hallmark of pancreatic necrosis is enzymatic fat necrosis of the endocrine and exocrine cells of the pancreas caused by the enzyme lipase. Fatty acids are released during this lipolytic process and combine with ionized calcium to form a soaplike product. The initial rapid lowering of serum calcium levels is not readily compensated for by the parathyroid gland. Because the body needs ionized calcium and cannot use bound calcium, hypocalcemia occurs.

Proteolysis involves the splitting of proteins by hydrolysis of the peptide bonds, resulting in the formation of smaller polypeptides. Proteolytic activity may lead to thrombosis and gangrene of the pancreas. Pancreatic destruction may be localized and confined to one area or may involve the entire organ.

Elastase is activated by trypsin and causes elastic fibers of the blood vessels and ducts to dissolve. The necrosis of blood vessels results in bleeding, ranging from minor bleeding to massive hemorrhage of pancreatic tissue. Another pancreatic enzyme, kallikrein, causes the release of vasoactive peptides, bradykinin, and a plasma kinin known as kallidin. These substances contribute to vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, further compounding the hemorrhagic process. This massive destruction of blood vessels by necrosis may lead to generalized hemorrhage with blood escaping into the retroperitoneal tissues. The patient with hemorrhagic pancreatitis is critically ill, and extensive pancreatic destruction and shock may lead to death. The majority of deaths in patients with acute pancreatitis result from irreversible shock.

The inflammatory stage occurs when leukocytes cluster around the hemorrhagic and necrotic areas of the pancreas. A secondary bacterial process may lead to suppuration (pus formation) of the pancreatic parenchyma or the formation of an abscess. (See discussion of Pancreatic Abscess on p. 1328.) Mild infected lesions may be absorbed. When infected lesions are severe, calcification and fibrosis occur. If the infected fluid becomes walled off by fibrous tissue, a pancreatic pseudocyst is formed. (See discussion of Pancreatic Pseudocyst on p. 1329.)

Complications of Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis may result in severe, life-threatening complications (Table 62-3). Jaundice occurs from swelling of the head of the pancreas, which slows bile flow through the common bile duct. The bile duct may also be compressed by calculi (stones) or a pancreatic pseudocyst. The resulting total bile flow obstruction causes severe jaundice. Intermittent hyperglycemia occurs from the release of glucagon, as well as the decreased release of insulin due to damage to the pancreatic islet cells. Total destruction of the pancreas may occur, leading to type 1 diabetes.

TABLE 62-3

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS