Chapter 62 Care of Patients with Problems of the Biliary System and Pancreas

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Collaborate with health care team members to provide care for patients with pancreatic disorders.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Teach people about health promotion practices to prevent gallbladder disease.

3. Teach people about health promotion practices to prevent pancreatitis.

4. Identify community-based resources for patients with pancreatic disorders.

5. Describe the psychosocial needs of patients with pancreatic cancer and their families.

6. Assess patient and family response to a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

7. Identify risk factors for gallbladder disease.

8. Interpret diagnostic test results associated with gallbladder disease.

9. Compare postoperative care of patients undergoing a traditional cholecystectomy with that of patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

10. Compare and contrast the pathophysiology of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

11. Interpret laboratory test results associated with acute pancreatitis.

12. Interpret common assessment findings associated with acute and chronic pancreatitis.

13. Prioritize nursing care for patients with acute pancreatitis and patients with chronic pancreatitis.

14. Explain the use and precautions associated with enzyme replacement for chronic pancreatitis.

15. Develop a postoperative plan of care for patients having a Whipple procedure.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy; Gallbladder Removal

Answers for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The biliary system (liver and gallbladder) and pancreas secrete enzymes and other substances that promote food digestion in the stomach and small intestine. When these organs do not work properly, the person has impaired digestion, which may result in inadequate nutrition. Collaborative care for patients with problems of the biliary system and pancreas includes the need to promote nutrition for healthy cellular function. This chapter focuses on problems of the gallbladder and pancreas. Liver disorders were described in Chapter 61.

Gallbladder Disorders

Cholecystitis

Pathophysiology

Cholecystitis is an inflammation of the gallbladder that affects many people, most commonly in affluent countries. It may be either acute or chronic, although most patients have the acute type. Over 500,000 surgeries for this health problem are done in the United States each year (Comstock, 2008).

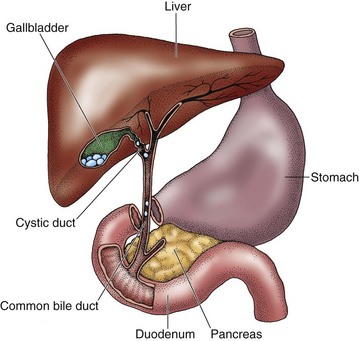

Acute Cholecystitis

Two types of acute cholecystitis can occur: calculous and acalculous cholecystitis. The most common type is calculous cholecystitis, in which chemical irritation and inflammation result from gallstones (cholelithiasis) that obstruct the cystic duct (most often), gallbladder neck, or common bile duct (choledocholithiasis) (Fig. 62-1). When the gallbladder is inflamed, trapped bile is reabsorbed and acts as a chemical irritant to the gallbladder wall; that is, the bile has a toxic effect. Reabsorbed bile, in combination with impaired circulation, edema, and distention of the gallbladder, causes ischemia and infection. The result is tissue sloughing with necrosis and gangrene. The gallbladder wall may eventually perforate (rupture). If the perforation is small and localized, an abscess may form. Peritonitis, infection of the peritoneum, may result if the perforation is large.

Gallstones are composed of substances normally found in bile, such as cholesterol, bilirubin, bile salts, calcium, and various proteins. They are classified as either cholesterol stones or pigment stones. Cholesterol calculi form as a result of metabolic imbalances of cholesterol and bile salts. They are the most common type found in people in the United States. Pigmented stones are associated with cirrhosis of the liver (McCance et al., 2010).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

A familial or genetic tendency appears to play a role in the development of cholelithiasis, but this may be partially related to familial nutrition habits (excessive dietary cholesterol intake) and sedentary lifestyles. Genetic-environment interactions may contribute to gallstone production (Attasaranya et al., 2008).

Cholelithiasis is seen more frequently in obese patients, probably as a result of impaired fat metabolism or increased cholesterol. The risk for developing gallstones increases as people age. Patients with diabetes mellitus are also at increased risk because they usually have higher levels of fatty acids (triglycerides). American Indians have a higher incidence of the disease than other groups, which may be due to the higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and obesity in this population (McCance et al., 2010). Risk factors for cholecystitis are listed in Table 62-1.

TABLE 62-1 RISK FACTORS FOR CHOLECYSTITIS

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Patients with acute cholecystitis present with abdominal pain, although clinical manifestations vary in intensity and frequency (Chart 62-1).

Cholecystitis

• Episodic or vague upper abdominal pain or discomfort that can radiate to the right shoulder

• Pain triggered by a high-fat or high-volume meal

• Feeling of abdominal fullness

• Rebound tenderness (Blumberg’s sign)

• Jaundice, clay-colored stools, dark urine, steatorrhea (most common with chronic cholecystitis)

Critical Rescue

Diagnostic Assessment

When the cause of cholecystitis or cholelithiasis is not known or the patient has manifestations of biliary obstruction (e.g., jaundice), an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed. Some patients have the less invasive and safer magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can be performed by an interventional radiologist. For this procedure, the patient is given oral or IV contrast material (gadolinium) before having a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Daniak et al., 2008). Before the test, ask the patient about any history of urticaria (hives) or other allergy. Gadolinium does not contain iodine, which decreases the risk for an allergic response. Chapter 55 discusses these tests in more detail.

Surgical Management

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

The laparoscopic procedure (often called a “lap chole”) is commonly done on an ambulatory care basis in a same-day surgery suite. The surgeon explains the procedure. The nurse answers questions and reinforces the physician’s instructions. Reinforce what to expect after surgery, and review pain management, deep-breathing exercises, and incentive spirometry use. There is no special preoperative preparation other than the routine preparation for surgery under general anesthesia described in Chapter 16. An IV antibiotic is usually given immediately before or during surgery.

During the surgery, the surgeon makes a very small midline puncture at the umbilicus. Additional small incisions may be needed, although single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) using a flexible endoscope can be done (Binenbaum et al., 2009). The abdominal cavity is insufflated with 3 to 4 L of carbon dioxide. Gasless laparoscopic cholecystectomy using abdominal wall lifting devices is a more recent innovation in some centers. This technique results in improved pulmonary and cardiac function. A trocar catheter is inserted, through which a laparoscope is introduced. The laparoscope is attached to a video camera, and the abdominal organs are viewed on a monitor. The gallbladder is dissected from the liver bed, and the cystic artery and duct are closed. The surgeon aspirates the bile and crushes any large stones and then extracts the gallbladder through the umbilical port.

Action Alert

A newer procedure is natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for removal of or repair of organs. Surgery can be performed on many body organs through the mouth, vagina, and rectum. For removal of the gallbladder, the vagina is used most often in women because it can be easily decontaminated with Betadine or other antiseptic and allows easy access into the peritoneal cavity. The surgeon makes a small internal incision through the cul-de-sac of Douglas between the rectum and uterine wall to access the gallbladder. The main advantages of this procedure are the lack of visible incisions and minimal, if any, postoperative complications (Navarra et al., 2010).

Traditional Cholecystectomy

The surgical nurse provides the usual preoperative care and teaching in the operating suite on the day of surgery (see Chapter 16). The surgeon removes the gallbladder through an incision and explores the biliary ducts for the presence of stones or other cause of obstruction. If the common bile duct is explored, the surgeon may insert a T-tube drain to ensure patency of the duct, although this is not done commonly today. Trauma to the common bile duct stimulates inflammation, which can slow bile flow and contribute to bile stasis. In addition, the surgeon usually inserts a drainage tube such as a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain. This tube is placed in the gallbladder bed to prevent fluid accumulation. The drainage is usually serosanguineous (serous fluid mixed with blood) and is stained with bile in the first 24 hours after surgery. Antibiotic therapy is given to prevent infection.

Patient care for a patient who has had a traditional open cholecystectomy is similar to the care for any patient who has had abdominal surgery under general anesthesia as described in Chapter 18. Postoperative incisional pain after a traditional cholecystectomy is controlled with opioids using a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. Encourage the patient to use coughing and deep-breathing exercises when pain is controlled and the incision is splinted.

Action Alert

Although PCS occurs in a small number of patients, patients who have it are usually discouraged that they have pain after already having surgery to cure it (Comstock, 2008). Causes of PCS are listed in Table 62-2. Management depends on the exact cause but usually involves the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to find the cause of the problem and repair it. This procedure and related nursing care are described in Chapter 55. Collaborative care includes pain management, antibiotics, nutrition and hydration therapy (possibly short-term parenteral nutrition), and control of nausea and vomiting.

TABLE 62-2 CAUSES OF POSTCHOLECYSTECTOMY SYNDROME

Physiological Integrity

A. Turn the client on the right side to help the flow of bile into the drainage bag.

B. Check that the nasogastric tube is connected to low intermittent suction.

C. Document the client’s use of the patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump.

D. Monitor the client’s oxygen saturation level via pulse oximetry.

Cancer Of The Gallbladder

Pathophysiology

Primary cancer of the gallbladder is rare and is more common in women than in men. Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer of the gallbladder account for the majority of the cases. The tumor tends to begin in the inner layer (mucosa) of the gallbladder wall. It then grows outward to include the entire gallbladder before it begins to metastasize (spread) to close organs like the liver, small intestine, and pancreas. These rare cancers appear more frequently in patients with pre-existing chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. They also tend to occur more often in American Indians than in any other group, but the reason for this finding is not known (McCance et al., 2010).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Interventions

Nursing care is similar to that for patients who have a cholecystectomy (see p. 1319) or Whipple procedure (see p. 1331), depending on the extent of disease. These procedures are described elsewhere in this chapter. Teach terminally ill patients and their families about end-of-life care and available hospice services (see Chapter 9).

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy alone are not effective for gallbladder cancer. However, they may be given as adjunctive procedures with surgery or instead of surgery in patients who are not surgical candidates to shrink the tumor. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy that is much more advanced and intense than regular radiation is used. Chemotherapy with 5-fluorourical (5-FU), doxorubicin, and mitomycin may be effective in reducing tumor size. Chapter 24 describes in detail the care of the patient receiving radiation and chemotherapy.

Pancreatic Disorders

Acute Pancreatitis

Pathophysiology

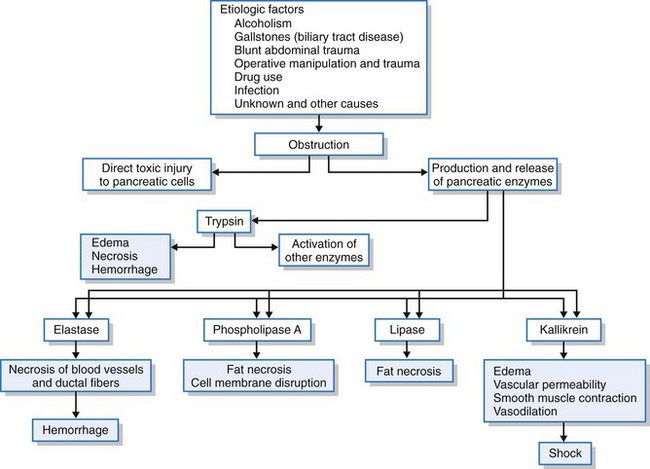

The pancreas is unusual in that it functions as both an exocrine gland and an endocrine gland. The primary endocrine disorder is diabetes mellitus and is discussed in Chapter 67. The exocrine function of the pancreas is responsible for secreting enzymes that assist in the breakdown of starches, proteins, and fats. These enzymes are normally secreted in the inactive form and become activated once they enter the small intestine. Early activation (i.e., activation within the pancreas rather than the intestinal lumen) results in the inflammatory process of pancreatitis. Direct toxic injury to the pancreatic cells and the production and release of pancreatic enzymes (e.g., trypsin, lipase, elastase) result from the obstructive damage. After pancreatic duct obstruction, increased pressure may contribute to ductal rupture allowing spillage of trypsin and other enzymes into the pancreatic parenchymal tissue. Autodigestion of the pancreas occurs as a result (Fig. 62-2). In acute pancreatitis, four major pathophysiologic processes occur: lipolysis, proteolysis, necrosis of blood vessels, and inflammation.

The inflammatory stage occurs when leukocytes cluster around the hemorrhagic and necrotic areas of the pancreas. A secondary bacterial process may lead to suppuration (pus formation) of the pancreatic parenchyma or the formation of an abscess. (See discussion of Pancreatic Abscess on p. 1328.) Mild infected lesions may be absorbed. When infected lesions are severe, calcification and fibrosis occur. If the infected fluid becomes walled off by fibrous tissue, a pancreatic pseudocyst is formed. (See discussion of Pancreatic Pseudocyst on p. 1329.)

Complications of Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis may result in severe, life-threatening complications (Table 62-3). Jaundice occurs from swelling of the head of the pancreas, which slows bile flow through the common bile duct. The bile duct may also be compressed by calculi (stones) or a pancreatic pseudocyst. The resulting total bile flow obstruction causes severe jaundice. Intermittent hyperglycemia occurs from the release of glucagon, as well as the decreased release of insulin due to damage to the pancreatic islet cells. Total destruction of the pancreas may occur, leading to type 1 diabetes.

TABLE 62-3 POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

• Pancreatic infection (causes septic shock) • Hemorrhage (necrotizing hemorrhagic pancreatitis [NHP]) Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|