Chapter 56 Care of Patients with Oral Cavity Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Plan continuity of care between the hospital and community-based agencies for patients having oral surgery.

2. Identify appropriate community resources for patients with oral cavity health problems.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Teach patients ways to prevent oral cancer and maintain good oral health.

4. Develop a teaching plan for patients who have stomatitis to promote digestion and nutrition.

5. Develop a teaching plan for community-based care of patients with oral cancer.

6. Identify the patient’s response to an oral cancer diagnosis.

7. Refer patients with oral cancer to appropriate support groups.

8. Prioritize postoperative care for patients undergoing surgery for oral cancer to maintain a patent airway and prevent aspiration.

9. Describe collaborative interventions to promote nutrition for postoperative patients having extensive oral surgery.

10. Identify methods to help patients communicate effectively after oral surgery.

11. Plan care for patients who have disorders of the salivary glands.

12. State best practices for teaching or providing oral care for patients.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Keys for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Oral cavity disorders, then, can severely affect nutrition and oxygenation, as well as speech, body image, and self-esteem. Although there are many oral health problems, this chapter discusses the most common disorders. Nurses play an important role in maintaining and restoring oral health through nursing interventions, including patient and family education. Chart 56-1 lists ways to help maintain a healthy oral cavity.

Chart 56-1 Patient And Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Maintaining a Healthy Oral Cavity

• Perform self-examination of your mouth every week; report any unusual finding or any noted change.

• Be sure to eat a well-balanced diet.

• Brush and floss your teeth every day. Set a routine, and keep to it. Keeping floss where you can see it (such as on the countertop by the sink) will encourage you to stick to your routine.

• Manage your stress as much as possible; learn how to maintain your emotional health by using healthy coping mechanisms.

• Avoid contact with agents that may cause inflammation of the mouth, such as mouthwashes that contain alcohol.

• If possible, avoid drugs that may cause inflammation of the mouth or reduce the flow of saliva.

• Be aware of any changes in the occlusion of your teeth, mouth pain, or swelling; seek medical attention promptly.

• See your dentist regularly; have problems attended to promptly.

• If you wear dentures, make sure they are in good repair and fit properly.

Stomatitis

Pathophysiology

Stomatitis is a broad term that refers to inflammation within the oral cavity and may present in many different ways. Painful single or multiple ulcerations (called aphthous ulcers or “canker sores”) that appear as inflammation and erosion of the protective lining of the mouth are one of the most common forms of stomatitis. The sores cause pain, and open areas place the person at risk for bleeding and infection. Mild erythema (redness) may respond to topical treatments. Extensive stomatitis may require treatment with opioid analgesics. Stomatitis is classified according to the cause of the inflammation. Primary stomatitis, the most common type, includes aphthous (noninfectious) stomatitis, herpes simplex stomatitis, and traumatic ulcers. Secondary stomatitis generally results from infection by opportunistic viruses, fungi, or bacteria in patients who are immunocompromised. It can also result from drugs, such as chemotherapy. (See Chapter 24 for discussion of chemotherapy-induced stomatitis.)

What Are Best Practices When Providing Oral Hygiene to Critically Ill Older Adults Who Are Orally Intubated?

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

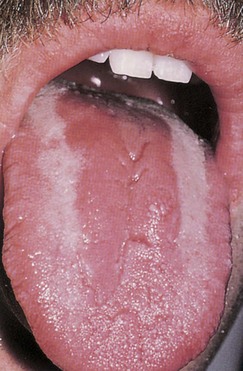

In oral candidiasis, a type of yeast infection, white plaque-like lesions appear on the tongue, palate, pharynx (throat), and buccal mucosa (inside the cheeks) (Fig. 56-1). When these patches are wiped away, the underlying surface is red and sore. Patients may report pain, but others describe the lesions as dry or hot. The older adult patient who has systemic illness or is taking antibiotics or chemotherapy is particularly susceptible to oral candidiasis.

Action Alert

Interventions

Interventions for stomatitis are targeted toward health promotion through careful oral hygiene and food selection. When providing mouth care for the patient, the nurse may delegate oral care to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). Because the accountability for the delegated task is the nurse’s, remind UAP to use a soft-bristled toothbrush or disposable foam swabs to stimulate gums and clean the oral cavity. Toothpaste should be free of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), if possible, because this ingredient has been associated with various types of stomatitis. Teach the patient to rinse the mouth every 2 to 3 hours with a sodium bicarbonate solution or warm saline solution (may be mixed with hydrogen peroxide). He or she should avoid most commercial mouthwashes because they have high alcohol content, causing a burning sensation in irritated or ulcerated areas. Health food stores sell more natural mouthwashes that are not alcohol-based. Teach the patient to check the labels for alcohol content. Frequent, gentle mouth care promotes débridement of ulcerated lesions and can prevent superinfections. Chart 56-2 lists measures for special oral care.

Chart 56-2 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Care of the Patient with Problems of the Oral Cavity

• Remove dentures if the patient has severe stomatitis or oral pain.

• Encourage the patient to perform oral hygiene or provide it after each meal and as often as needed.

• Increase mouth care to every 2 hours or more frequently if stomatitis is not controlled.

• Use a soft toothbrush or gauze for oral care.

• Encourage frequent rinsing of the mouth with warm saline or sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) solution, or a combination of these solutions.

• Teach the patient to avoid commercial mouthwashes, particularly those with high alcohol content, and lemon-glycerin swabs.

• Assist the patient in selecting soft, bland, and nonacidic foods.

• Apply topical analgesics or anesthetics as prescribed by the health care provider, and monitor their effectiveness.

Immune modulating agents that may be prescribed include:

Physiological Integrity

Oral Tumors

Oral Cancer

Prevention strategies for oral cancer include minimizing sun and tanning bed exposure, tobacco cessation, and decreasing alcohol intake. Most dentists now use digital technology instead of x-rays when performing the annual or biannual dental examination. Excessive, prolonged radiation from x-rays has been associated with head and neck cancer (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). Teach patients to follow the guidelines in Chart 56-1 to maintain oral health.

Pathophysiology

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

More than 90% of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas that begin on the surface of the epithelium. Over a period of many years, premalignant (or dysplastic) changes begin. Cells begin to vary in size and shape. Alterations in the thickness of the lining of the epithelium develop, resulting in atrophy. These tumors usually grow slowly, and the lesions may be large before the onset of symptoms unless ulceration is present. Mucosal erythroplasia is the earliest sign of oral carcinoma. Oral lesions that appear as red, raised, eroded areas are suspicious for cancer. A lesion that does not heal within 2 weeks or a lump or thickening in the cheek is a symptom that warrants further assessment (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010).

Squamous cell cancer can be found on the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, and oropharynx. The major risk factors in its development are increasing age, tobacco use, and alcohol use. Most oral cancers occur in people older than 40 years. Tobacco use in any form (e.g., smoking or chewing tobacco) can increase the risk for cancer. A person who frequently consumes alcohol and uses tobacco in any form is at the highest risk. Genetic changes in patients with oral cancer have been found, especially the mutation of the TP53 gene (McCance et al., 2010).

An increased rate of oral cancer is found in people with occupations such as textile workers, plumbers, and coal and metal workers. Additional factors, such as sun exposure, poor nutritional habits, poor oral hygiene, and infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV16) may also contribute to oral cancer (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). People with periodontal (gum) disease in which mandibular (jaw) bone loss has occurred are especially at risk for cancer of the mouth.

Mouth cancers account for about 3% of all cancers in men and 2% of all cancers in women in the United States. Over 37,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, with almost 8000 deaths (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). Most cancers occur in middle-aged and older people, although in recent years, younger adults have been affected, probably as a result of sun exposure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree