Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Noninflammatory Intestinal Disorders

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

7 Develop a teaching-learning plan for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

8 Differentiate the most common types of hernias.

9 Develop a plan of care for a patient undergoing a minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair.

10 Identify risk factors for CRC.

11 Interpret assessment findings for patients with CRC.

12 Explain the role of the nurse in managing the patient with CRC.

13 Develop a perioperative plan of care for a patient undergoing a colon resection and colostomy.

14 Explain the differences between small-bowel and large-bowel obstructions.

15 Develop a plan of care for a patient with an intestinal obstruction to promote elimination.

16 Describe the postoperative care for a patient having a hemorrhoid surgical procedure.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Nasogastric Tube Placement

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Concept Map Creator

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Intestinal health problems may be inflammatory or noninflammatory. This chapter describes those disorders that are noninflammatory in origin. Noninflammatory intestinal problems often cause rectal bleeding, changing bowel patterns, and abdominal pain. If not diagnosed and managed early, some intestinal problems can lead to inadequate absorption of vital nutrients and therefore affect the need for nutrition and elimination.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional GI disorder that causes chronic or recurrent diarrhea, constipation, and/or abdominal pain and bloating. It is sometimes referred to as spastic colon, mucous colon, or nervous colon (Fig. 59-1). IBS is the most common digestive disorder seen in clinical practice and may affect as many as one in five people in the United States.

In most patients, no actual pathophysiologic bowel changes occur. However, microscopic inflammatory changes have recently been found in some patients with the disease due to bacterial overgrowth and subsequent infection.

In patients with IBS, bowel motility changes and increased or decreased bowel transit times result in changes in the normal bowel elimination pattern to one of these classifications: diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), alternating diarrhea and constipation (IBS-A), or a mix of diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M). Symptoms of the disease typically begin to appear in young adulthood and continue throughout the patient’s life.

The etiology of IBS remains unclear. Recent research suggests that a combination of environmental, immunologic, genetic, hormonal, and stress factors play a role in the development and course of the disease. Examples of environmental factors include foods and fluids like caffeinated or carbonated beverages and dairy products. Infectious agents have also been identified. Several recent studies have found that patients with IBS often have small-bowel bacterial overgrowth, which causes bloating and abdominal distention. Multiple normal flora and pathogenic agents have been identified, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kerckhoffs et al., 2011). Other researchers believe that these agents are less causative and serve as measurable biomarkers for the disease (Malinen et al., 2010).

Immunologic and genetic factors have also been associated with IBS, especially cytokine genes, including pro-inflammatory interleukins (IL) such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha (Barkhordari et al., 2010). These findings may provide the basis of targeted drug therapy for the disease.

In the United States, women are two times more likely to have IBS than men. This difference may be the result of hormonal differences. However, in other areas of the world, this distribution pattern may not occur. For example, researchers found that there is not a female predominance for the disease in Asian countries (Gwee et al., 2010).

Considerable evidence relates the role of stress and mental or behavioral illness, especially anxiety and depression, to IBS. Many patients diagnosed with IBS meet the criteria for at least one primary mental health disorder. Some researchers suggest that psychosocial problems may be a cause for IBS (Nicholl et al., 2008). However, the pain and other chronic symptoms of the disease may lead to secondary mental health disorders. For example, when diarrhea is predominant, patients fear that there will be no bathroom facilities available and can become very anxious. The long-term nature of dealing with a chronic disease for which there is no cure can lead to secondary depression in some patients.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Ask the patient about a history of weight change, fatigue, malaise, abdominal pain, changes in the bowel pattern (constipation, diarrhea, or an alternating pattern of both) or consistency of stools, and the passage of mucus. Patients with IBS do not usually lose weight. Ask whether the patient has had any GI infections. Collect information on all drugs the patient is taking, because some of them can cause symptoms similar to those of IBS. Ask about the nutrition history, including the use of caffeinated drinks or beverages sweetened with sorbitol or fructose, which can cause bloating or diarrhea.

The course of the illness is specific to each patient. Most patients can identify factors that cause exacerbations, such as diet, stress, or anxiety. Food intolerance may be associated with IBS. Dairy products (e.g., lactose intolerance), raw fruits, and grains can contribute to bloating, flatulence (gas), and abdominal distention.

A flare-up of worsening cramps, abdominal pain, and diarrhea and/or constipation may bring the patient to the health care provider. One of the most common concerns of patients with IBS is pain in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. Assess the location, intensity, and quality of the pain. Some patients have internal visceral (organ) hypersensitivity that can cause or contribute to the pain. Nausea may be associated with mealtime and defecation. The constipated stools are small and hard and are generally followed by several softer stools. The diarrheal stools are soft and watery, and mucus is often present in the stools. Patients with IBS often report belching, gas, anorexia, and bloating.

The patient generally appears well, with a stable weight, and nutritional and fluid status are within normal ranges. Inspect and auscultate the abdomen. Bowel sounds vary but are generally within normal range. With constipation, bowel sounds may be hypoactive; with severe diarrhea, they may be hyperactive.

Routine laboratory values (including a complete blood count [CBC], serum albumin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], and stools for occult blood) are normal in IBS. Some health care providers request a hydrogen breath test (Lindberg, 2009). When small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth or malabsorption of nutrients is present, excess hydrogen is produced. Some of this hydrogen is absorbed into the bloodstream and travels to the lungs where it is exhaled. Patients with IBS often have an increased amount of hydrogen during exhalation.

Teach the patient that he or she will need to be NPO (may have water) for at least 12 hours before the hydrogen breath test. At the beginning of the test, the patient blows into a hydrogen analyzer. Then, small amounts of test sugar are ingested, depending on the purpose of the test, and additional breath samples are taken every 15 minutes for 1 hour or longer. If lactose tolerance is evaluated, lactose is ingested. If bacterial overgrowth is tested, lactulose is given (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Interventions

The patient with IBS is usually cared for in an ambulatory care setting and learns self-management strategies. Interventions include health teaching, drug therapy, and stress reduction. Some patients also use complementary and alternative therapies. A holistic approach to patient care is essential for positive outcomes (Bengtsson et al., 2010).

Keeping a symptom diary in which the patient records potential triggers and bowel habits for a period of time can assist in identifying triggers for disease symptoms. Assist patients to identify and avoid specific foods that they cannot tolerate. These foods may include caffeine, alcohol, egg, wheat products, beverages that contain sorbitol or fructose, and other gastric irritants. Milk and milk products should be avoided if lactose intolerance is suspected. In this case, teach patients to use lactose-free or soy products as substitutes. Patients who are lactose intolerant need to increase intake of calcium-rich, lactose-free foods or take a calcium supplement because they are at high risk for osteoporosis.

Dietary fiber and bulk help produce bulky, soft stools and establish regular bowel habits. The patient should ingest about 30 to 40 g of fiber each day. Eating regular meals, drinking 8 to 10 cups of liquid each day, and chewing food slowly help promote normal bowel function. If needed, collaborate with the dietitian to help the patient and family with meal planning.

Drug therapy depends on the predominant symptom of IBS. The health care provider may prescribe bulk-forming or antidiarrheal agents and/or newer drugs to control symptoms.

For the treatment of constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C), bulk-forming laxatives, such as psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid (Metamucil), are generally taken at mealtimes with a glass of water. The hydrophilic properties of these drugs help prevent dry, hard, or liquid stools. Lubiprostone (Amitiza) is a new oral drug available for women with IBS-C. The drug is not effective for men. Lubiprostone is classified as a locally acting chloride channel activator that increases intestinal chloride without affecting intestinal sodium and potassium concentrations. Teach the patient to take the drug with food and water.

Diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) may be treated with antidiarrheal agents, such as loperamide (Imodium), and psyllium (a bulk-forming agent). Alosetron (Lotronex), a selective serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, may be used with caution in women with IBS-D as a last resort when they have not responded to conventional therapy. Patients taking this drug must agree to report symptoms of colitis or constipation early because it is associated with potentially life-threatening bowel complications.

Many patients with IBS who have bloating and abdominal distention without constipation have success with rifaximin (Xifaxan), an antibiotic that works locally with little systemic absorption (Pimental et al., 2011). Although the drug has been approved for “traveler’s diarrhea” and other illnesses, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved its use for patients with IBS.

A newer group of drugs called muscarinic-receptor antagonists also inhibit intestinal motility. Some of these agents have been approved for people with overactive bladders but have not yet received FDA approval for IBS. Examples in this group currently undergoing clinical trials are darifenacin (Enablex) and fesoterodine (Toviaz).

For IBS in which pain is the predominant symptom, tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline (Elavil) have also been successfully used. It is unclear whether their effectiveness is due to the antidepressant or anticholinergic effects of the drugs. If patients have postprandial (after eating) discomfort, they should take these drugs 30 to 45 minutes before mealtime.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

For patients with increased intestinal bacterial overgrowth, recommend daily probiotic supplements. Probiotics have been shown to be effective for reducing bacteria and successfully alleviating GI symptoms of IBS (Lyra et al., 2010). There is also evidence that peppermint oil capsules may be effective in reducing symptoms for patients with IBS (Pirotta, 2009).

Acupuncture and moxibustion (Acu-Moxa) treatment has helped some patients by reducing flatulence and bloating and improving stool consistency (Anastasi et al., 2009). Moxibustion is the use of herbs to facilitate healing. Encourage patients to try these therapies, especially if they can be reimbursed by insurance companies. Third-party payers are becoming more sensitive to the use of these proven therapies as adjuncts in holistic disease management.

Stress management is also an important part of holistic care. Suggest relaxation techniques, meditation, and/or yoga to help the patient decrease GI symptoms. If the patient is in a stressful work or family situation, personal counseling may be helpful. Based on patient preference, make appropriate referrals or assist in making appointments, if needed. The opportunity to discuss problems and attempt creative problem solving is often helpful. Teach the patient that regular exercise is important for managing stress and promoting regular bowel elimination.

Herniation

Pathophysiology

A hernia is a weakness in the abdominal muscle wall through which a segment of the bowel or other abdominal structure protrudes. Hernias can also penetrate through any other defect in the abdominal wall, through the diaphragm, or through other structures in the abdominal cavity.

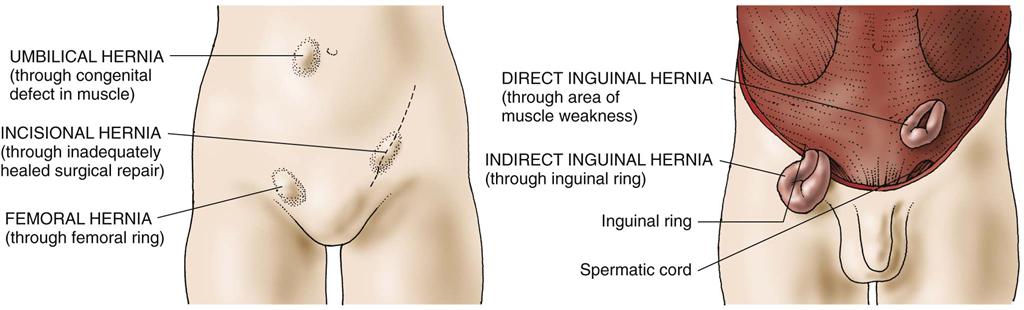

The most common types of abdominal hernias (Fig. 59-2) are indirect, direct, femoral, umbilical, and incisional.

• Direct inguinal hernias, in contrast, pass through a weak point in the abdominal wall (Fig. 59-3).

Hernias may also be classified as reducible, irreducible (incarcerated), or strangulated. A hernia is reducible when the contents of the hernial sac can be placed back into the abdominal cavity by gentle pressure. An irreducible (incarcerated) hernia cannot be reduced or placed back into the abdominal cavity. Any hernia that is not reducible requires immediate surgical evaluation.

A hernia is strangulated when the blood supply to the herniated segment of the bowel is cut off by pressure from the hernial ring (the band of muscle around the hernia). If a hernia is strangulated, there is ischemia and obstruction of the bowel loop. This can lead to necrosis of the bowel and possibly bowel perforation. Signs of strangulation are abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, pain, fever, and tachycardia.

The most important elements in the development of a hernia are congenital or acquired muscle weakness and increased intra-abdominal pressure. The most significant factors contributing to increased intra-abdominal pressure are obesity, pregnancy, and lifting heavy objects.

Indirect inguinal hernias, the most common type, are most common in men because they follow the tract that develops when the testes descend into the scrotum before birth. Direct hernias occur more often in older adults. Femoral and adult umbilical hernias are most common in obese or pregnant women. Incisional hernias can occur in people who have undergone abdominal surgery.

Defects in the muscle wall result from weakened collagen or widened spaces at the inguinal ligament. These muscle weaknesses can be inherited or acquired as part of the aging process. Increases in intra-abdominal pressure as a result of pregnancy, obesity, abdominal distention, ascites, heavy lifting, or coughing can contribute to their occurrence.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Even though the muscle weakness cannot be prevented, exercises can strengthen muscles. Obesity is considered a contributing factor because it causes increased intra-abdominal pressure. Weight control helps decrease the likelihood of hernias by decreasing pressure on the abdominal muscles. Heavy lifting and straining also increase intra-abdominal pressure and should be avoided.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The patient with a hernia typically comes to the health care provider’s office or the emergency department with a report of a “lump” or protrusion felt at the involved site. The development of the hernia may be associated with straining or lifting.

Perform an abdominal assessment inspecting the abdomen when the patient is lying and again when he or she is standing. If the hernia is reducible, it may disappear when the patient is lying flat. The advanced practice nurse or other health care provider asks the patient to strain or perform the Valsalva maneuver and observes for bulging. Auscultate for active bowel sounds. Absent bowel sounds may indicate obstruction and strangulation, which is a medical emergency!

To palpate an inguinal hernia, the health care provider gently examines the ring and its contents by inserting a finger in the ring and noting any changes when the patient coughs. The hernia is never forcibly reduced; that maneuver could cause strangulated intestine to rupture.

If a male patient suspects a hernia in his groin, the health care provider has him stand for the examination. Using the right hand for the patient’s right side and the left hand for the patient’s left side, the examiner pushes in the loose scrotal skin with the index finger, following the spermatic cord upward to the external inguinal cord. At this point, the patient is asked to cough, and any palpable herniation is noted.

Interventions

The type of treatment selected depends on patient factors such as age, as well as the type and severity of the hernia.

Nonsurgical Management

If the patient is not a surgical candidate, often an older adult with multiple health problems, the health care provider may prescribe a truss for an inguinal hernia, most often for men. A truss is a pad made with firm material. It is held in place over the hernia with a belt to help keep the abdominal contents from protruding into the hernial sac. If a truss is used, it is applied only after the physician has reduced the hernia if it is not incarcerated. The patient usually applies the truss upon awakening. Teach him to assess the skin under the truss daily and to protect it with a light layer of powder.

Surgical Management

Most hernias are inguinal. Surgical repair of a hernia is the treatment of choice. Surgery is usually performed on an ambulatory care basis for patients who have no pre-existing health conditions that would complicate the operative course. In same-day surgery centers, anesthesia may be regional or general and the surgery is typically laparoscopic. More extensive surgery, such as a bowel resection or temporary colostomy, may be necessary if strangulation results in a gangrenous section of bowel. Patients undergoing extensive surgery are hospitalized for a longer period.

A minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair (MIIHR) through a laparoscope, also called herniorrhaphy, is the surgery of choice. A conventional open herniorrhaphy may be performed when laparoscopy is not appropriate. Patients having minimally invasive surgery (MIS) recover more quickly, have less pain, and develop fewer postoperative complications compared with those having the conventional surgery.

In addition to patient education about the procedure, the most important preoperative preparation is to teach the patient to remain NPO for the number of hours before surgery that the surgeon specifies. If same-day surgery is planned, remind the patient to arrange for someone to take him or her home and be available for the rest of the day at home. For patients having an open surgical approach, provide general preoperative care as described in Chapter 16.

During an MIIHR, the surgeon makes several small incisions, identifies the defect, and places the intestinal contents back into the abdomen. During a traditional herniorrhaphy, the surgeon makes an abdominal incision to perform this procedure. When a hernioplasty is also performed, the surgeon reinforces the weakened outside abdominal muscle wall with a mesh patch.

The patient who has had MIIHR is discharged from the surgical center in 3 to 5 hours, depending on recovery from anesthesia. Teach him or her to rest for several days before returning to work and a normal routine. Caution patients who are taking oral opioids for pain management to not drive or operate heavy machinery. Teach them to observe incisions for redness, swelling, heat, drainage, and increased pain and promptly report their occurrence to the surgeon. Remind patients that soreness and discomfort rather than severe, acute pain are common after MIS. Be sure to make a follow-up telephone call on the day after surgery to check on the patient’s status.

General postoperative care of patients having a hernia repair is the same as that described in Chapter 18 except that they should avoid coughing. To promote lung expansion, encourage deep breathing and ambulation. With repair of an indirect inguinal hernia, the physician may suggest a scrotal support and ice bags applied to the scrotum to prevent swelling, which often contributes to pain. Elevation of the scrotum with a soft pillow helps prevent and control swelling.

In the immediate postoperative period, male patients who have had an inguinal hernia repair may experience difficulty voiding. Encourage them to stand to allow a more natural position for gravity to facilitate voiding and bladder emptying. Urine output of less than 30 mL per hour should be reported to the surgeon. Techniques to stimulate voiding such as allowing water to run may also be used. A fluid intake of at least 1500 to 2500 mL daily prevents dehydration and maintains urinary function. A “straight” or intermittent catheterization is required if the patient cannot void.

Most patients have uneventful recoveries after a hernia repair. Surgeons generally allow them to return to their usual activities after surgery, with avoidance of straining and lifting for several weeks while subcutaneous tissues heal and strengthen.

Provide oral instructions and a written list of symptoms to be reported, including fever, chills, wound drainage, redness or separation of the incision, and increasing incisional pain. Teach the patient to keep the wound dry and clean with antibacterial soap and water. Showering is usually permitted in a few days.

Colorectal Cancer

Pathophysiology

Colorectal refers to the colon and rectum, which together make up the large intestine, also known as the large bowel. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is cancer of the colon or rectum and is a major health problem worldwide. In the United States, it is one of the most common malignancies.

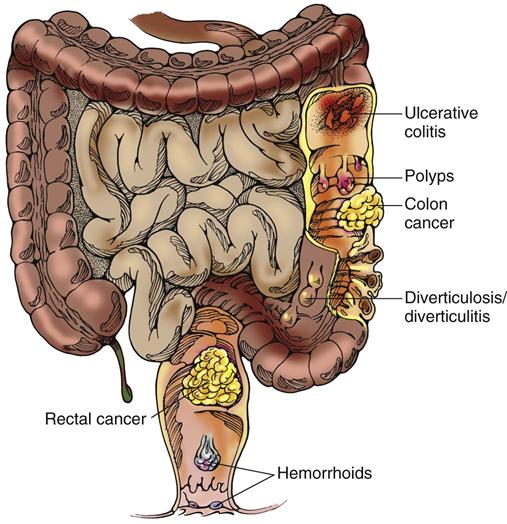

Most CRCs are adenocarcinomas, which are tumors that arise from the glandular epithelial tissue of the colon. They develop as a multi-step process, resulting in a number of molecular changes, such as loss of key tumor suppressor genes and activation of certain oncogenes that alter colonic mucosa cell division. The increased proliferation of the colonic mucosa forms polyps that can transform into malignant tumors. Most CRCs are believed to arise from adenomatous polyps that present as a visible protrusion from the mucosal surface of the bowel (McCance et al., 2010).

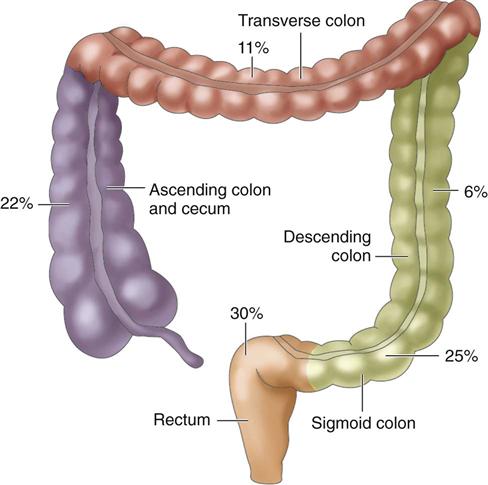

Tumors occur in different areas of the colon, with about two thirds occurring within the rectosigmoid region. The percentages in Fig. 59-4 indicate an increased incidence of cancer in the proximal sections of the large intestine over the past 35 years.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) can metastasize by direct extension or by spreading through the blood or lymph. The tumor may spread locally into the four layers of the bowel wall and into neighboring organs. It may enlarge into the lumen of the bowel or spread through the lymphatics or the circulatory system. The circulatory system is entered directly from the primary tumor through blood vessels in the bowel or via the lymphatics. The liver is the most frequent site of metastasis from circulatory spread. Metastasis to the lungs, brain, bones, and adrenal glands may also occur. Colon tumors can also spread by peritoneal seeding during surgical resection of the tumor. Seeding may occur when a tumor is excised and cancer cells break off from the tumor into the peritoneal cavity. For this reason, special techniques are used during surgery to decrease this possibility.

Complications related to the increasing growth of the tumor locally or through metastatic spread include bowel obstruction or perforation with resultant peritonitis, abscess formation, and fistula formation to the urinary bladder or the vagina. The tumor may invade neighboring blood vessels and cause frank bleeding. Tumors growing into the bowel lumen can gradually obstruct the intestine and eventually block it completely. Those extending beyond the bowel wall may place pressure on neighboring organs (uterus, urinary bladder, and ureters) and cause symptoms that mask those of the cancer. Chapter 23 discusses cancer pathophysiology in more detail.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

The major risk factors for the development of colorectal cancer (CRC) include being older than 50 years, genetic predisposition, personal or family history of cancer, and/or diseases that predispose the patient to cancer such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis (McCance et al., 2010). Only a small percentage of colorectal cancers are familial and transmitted genetically.

The role of infectious agents in the development of colorectal and anal cancer continues to be investigated. Some lower GI cancers are related to Helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus bovis, JC virus, and human papilloma virus (HPV) infections.

There is also strong evidence that long-term smoking, increased body fat, physical inactivity, and heavy alcohol consumption are risk factors for colorectal cancer (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010). A high-fat diet, particularly animal fat from red meats, increases bile acid secretion and anaerobic bacteria, which are thought to be carcinogenic within the bowel. Diets with large amounts of refined carbohydrates that lack fiber decrease bowel transit time.

Incidence/Prevalence

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer death in the United States (ACS, 2010). It is not common before 40 years of age, but the incidence in younger adults is slowly increasing, most likely due to increases in HPV infections (Stubenrauch, 2010). The overall incidence of CRC has decreased over the past 10 years, most likely as a result of increased cancer screenings. The disease is most common in African Americans, and their survival rate is lower than that of Euro-Americans (Caucasians). The possible reasons for this difference include less use of diagnostic testing (especially colonoscopy), decreased access to health care, cultural beliefs, and lack of education about the need for early cancer detection (Good et al., 2010; Hamlyn, 2008).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

People at risk can take action to decrease their chance of getting CRC and/or increase their chance of surviving it. For example, those whose family members have had hereditary CRC should be genetically tested for FAP and HNPCC. If gene mutations are present, the person at risk can collaborate with the health care team to decide what prevention or treatment plan to implement.

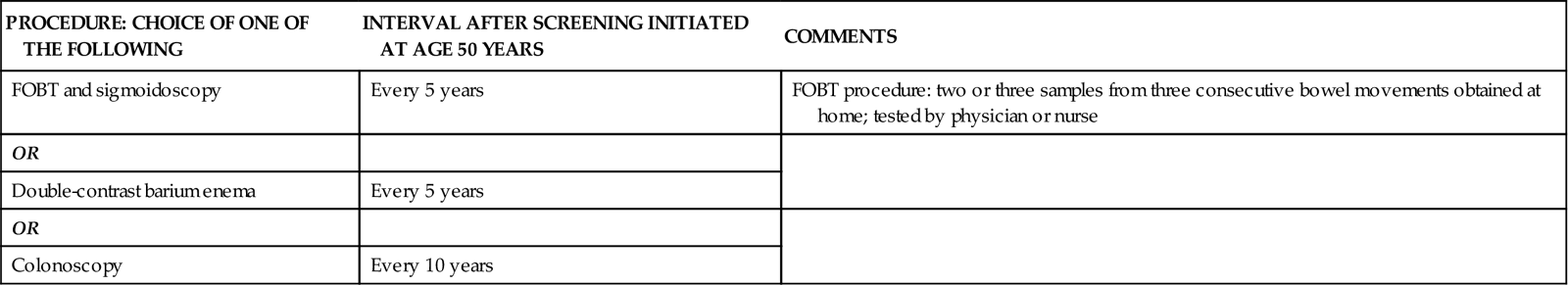

Teach people about the need for diagnostic screening. When an adult turns 40 years of age, he or she should discuss with the health care provider about the need for colon cancer screening. The interval depends on level of risk. People of average risk who are 50 years of age and older, without a family history, should undergo regular CRC screening. The screening includes fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) and colonoscopy every 10 years or double-contrast barium enema every 5 years. People who have a personal or family history of the disease should begin screening earlier and more frequently (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2008). Teach all patients to follow the American Cancer Society recommendations for CRC screening listed in Chart 59-1.

Teach patients, regardless of risk, to modify their diets as needed to decrease fat, refined carbohydrates, and low-fiber foods. Encourage baked or broiled foods, especially those high in fiber and low in animal fat. Teach people the hazards of smoking, excessive alcohol, and physical inactivity. Refer patients as needed for smoking- or alcohol-cessation programs, and recommend ways to increase regular physical exercise.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

When taking a history, ask the patient about major risk factors, such as a personal history of breast, ovarian, or endometrial cancer (which can spread to the colon); ulcerative colitis; Crohn’s disease; familial polyposis or adenomas; polyps, or a family history of CRC. Also assess the patient’s participation in age-specific cancer screening guidelines. Ask about whether the patient uses tobacco and/or alcohol. Assess the patient’s usual physical activity level.

Ask whether vomiting and changes in bowel habits, such as constipation or change in shape of stool with or without blood, have been noted. The patient may also report fatigue (related to anemias), abdominal fullness, vague abdominal pain, or unintentional weight loss. These symptoms suggest advanced disease.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of CRC depend on the location of the tumor. However, the most common signs are rectal bleeding, anemia, and a change in stool consistency or shape. Stools may contain microscopic amounts of blood that are not noticeably visible, or the patient may have mahogany (dark)-colored or bright red stools (Fig. 59-5). Gross blood is not usually detected with tumors of the right side of the colon but is common (but not massive) with tumors of the left side of the colon and the rectum.

Tumors in the transverse and descending colon result in symptoms of obstruction as growth of the tumor blocks the passage of stool. The patient may report “gas pains,” cramping, or incomplete evacuation. Tumors in the rectosigmoid colon are associated with hematochezia (the passage of red blood via the rectum), straining to pass stools, and narrowing of stools. Patients may report dull pain. Right-sided tumors can grow quite large without disrupting bowel patterns or appearance because the stool consistency is more liquid in this part of the colon. These tumors ulcerate and bleed intermittently, so stools can contain dark or mahogany-colored blood. A mass may be palpated in the lower right quadrant, and the patient often has anemia secondary to blood loss.

Examination of the abdomen begins with assessment for obvious distention or masses. Visible peristaltic waves accompanied by high-pitched or “tinkling” bowel sounds may indicate a partial bowel obstruction from the tumor. Total absence of bowel sounds indicates a complete bowel obstruction. Palpation and percussion are performed by the advanced practice nurse or other health care provider to determine whether the spleen or liver is enlarged or whether masses are present along the colon. The examiner may also perform a digital rectal examination to palpate the rectum and lower sigmoid colon for masses. Fecal occult blood screening should not be done with a specimen from a rectal examination because it is not reliable.

Psychosocial Assessment

The psychological consequences associated with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) are many. Patients must cope with a diagnosis that instills fear and anxiety about treatment, feelings that life has been disrupted, a need to search for ways to deal with the diagnosis, and concern about family. They also have questions about why colon cancer affected them, as well as concerns about pain, possible disfigurement, and possible death. In addition, if the cancer is believed to have a genetic origin, there is anxiety concerning implications for immediate family members.

Laboratory Assessment

Hemoglobin and hematocrit values are often decreased as a result of the intermittent bleeding associated with the tumor. For some patients, that may be the first indication that a tumor is present. CRC that has metastasized to the liver causes liver function tests to be elevated.

A positive test result for occult blood in the stool (fecal occult blood test [FOBT]) indicates bleeding in the GI tract. These tests can yield false-positive results if certain vitamins or drugs are taken before the test. Remind the patient to avoid aspirin, vitamin C, and red meat for 48 hours before giving a stool specimen. Also assess whether the patient is taking anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, corticosteroids, or salicylates). These drugs should be discontinued for a designated period before the test. Two or three separate stool samples should be tested on 3 consecutive days. Negative results do not completely rule out the possibility of CRC.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), an oncofetal antigen, is elevated in many people with CRC. The normal value is less that 5 ng/mL or 5 mcg/L (SI units) (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). This protein is not specifically associated with the colorectal cancer, and it may be elevated in the presence of other benign or malignant diseases and in smokers. CEA is often used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment and to identify disease recurrence.

Imaging Assessment

A double-contrast barium enema (air and barium are instilled into the colon) or colonoscopy provides better visualization of polyps and small lesions than a barium enema alone. These tests may show an occlusion in the bowel where the tumor is decreasing the size of the lumen.

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, lungs, or liver helps confirm the existence of a mass, the extent of disease, and the location of distant metastases. CT-guided virtual colonoscopy is growing in popularity and may be more thorough than traditional colonoscopy. However, treatments or surgeries cannot be performed when a virtual colonoscopy is used.

Other Diagnostic Assessment

A sigmoidoscopy provides visualization of the lower colon using a fiberoptic scope. Polyps can be visualized, and tissue samples can be taken for biopsy. Polyps are usually removed during the procedure. A colonoscopy provides views of the entire large bowel from the rectum to the ileocecal valve. As with sigmoidoscopy, polyps can be seen and removed, and tissue samples can be taken for biopsy. Colonoscopy is the definitive test for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. These procedures and associated nursing care are discussed in Chapter 55.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) include:

Planning and Implementation

The primary approach to treating CRC is to remove the entire tumor or as much of the tumor as possible to prevent or slow metastatic spread of the disease. A patient-centered collaborative care approach is essential to meet the desired outcomes.

Preventing or Controlling Metastasis

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with colorectal cancer (CRC) is expected to not have the cancer spread to vital organs. Thus the patient’s life expectancy will be increased and the quality of life will be improved. However, if metastasis is present, the desired outcome is to ensure that the patient is as comfortable as possible and pain is well-managed.

Interventions.

Although surgical resection is the primary means used to control the disease, several adjuvant (additional) therapies are used. Adjuvant therapies are administered before or after surgery to achieve a cure, if possible, and to prevent recurrence.

Nonsurgical Management.

The type of therapy used is based on the pathologic staging of the disease. Several staging systems may be used. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system uses this broad staging classification and description:

• Stage I—Tumor invades up to muscle layer

• Stage II—Tumor invades up to other organs or perforates peritoneum

• Stage III—Any level of tumor invasion and up to 4 regional lymph nodes

• Stage IV—Any level of tumor invasion; many lymph nodes affected with distant metastases

Radiation Therapy.

The administration of preoperative radiation therapy has not improved overall survival rates for colon cancer, but it has been effective in providing local or regional control of the disease. Postoperative radiation has not demonstrated any consistent improvement in survival or recurrence. However, as a palliative measure, radiation therapy may be used to control pain, hemorrhage, bowel obstruction, or metastasis to the lung in advanced disease. For rectal cancer, unlike colon cancer, radiation therapy is almost always a part of the treatment plan. Reinforce information about the radiation therapy procedure to the patient and family, and monitor for possible side effects (e.g., diarrhea, fatigue). Chapter 24 describes the general care of patients undergoing radiation therapy.

Drug Therapy.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after primary surgery is recommended for patients with stage II or stage III disease to interrupt the DNA production of cells and improve survival. The drugs of choice are IV 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) with leucovorin (LV) (folinic acid), capecitabine (Xeloda), or a combination of drugs referred to as FOLFOX. The most frequently used FOLFOX combination for metastatic CRC is 5-FU (fluorouracil), leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (Eloxatin), a platinum analog. These drugs cannot discriminate between cancer and healthy cells. Therefore common side effects are diarrhea, mucositis, leukopenia, mouth ulcers, and peripheral neuropathy.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) is the first antiangiogenesis drug to be approved for advanced CRC. This type of drug reduces blood flow to the growing tumor cells, thereby depriving them of necessary nutrients needed to grow. It is usually given in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents.

Cetuximab (Erbitux), a monoclonal antibody, may also be given for advanced disease. This drug works by blocking factors that promote cancer cell growth. Cetuximab is usually given in combination with another drug.

Intrahepatic arterial chemotherapy, often with 5-FU, may be administered to patients with liver metastasis. Patients with CRC also receive drugs for relief of symptoms, such as opioid analgesics and antiemetics.

Surgical Management.

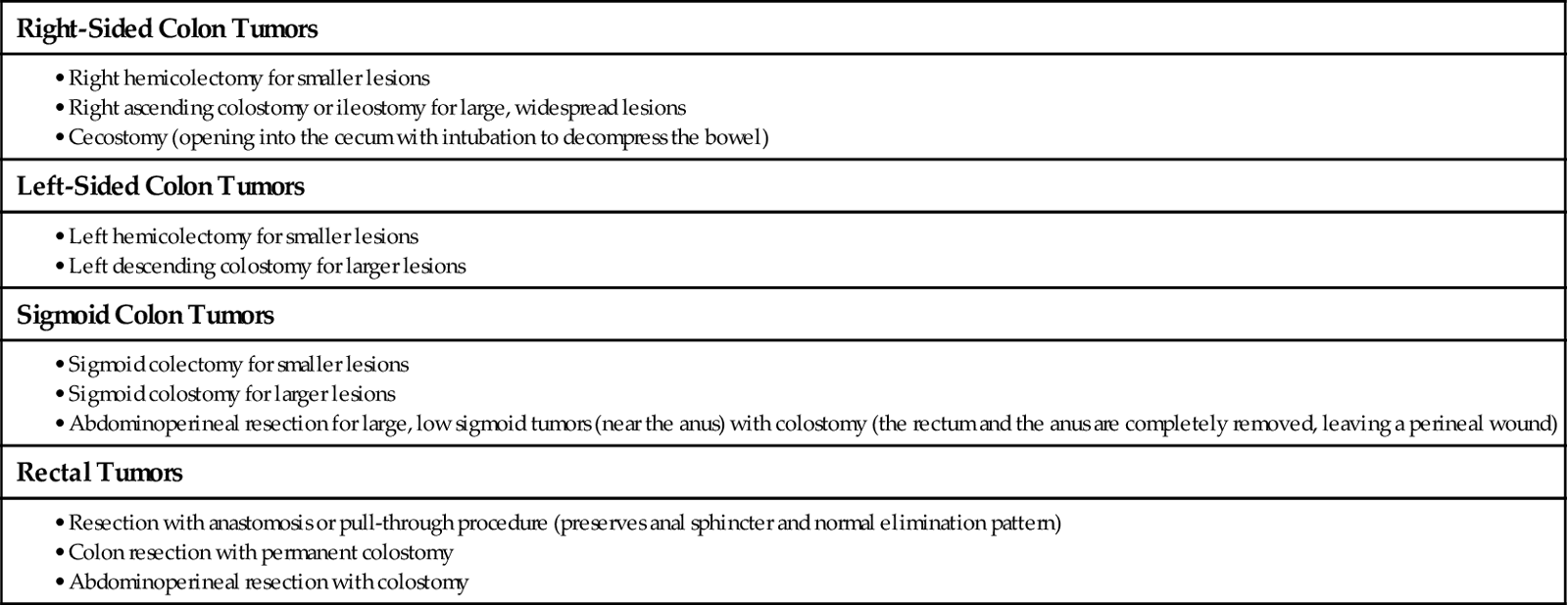

Surgical removal of the tumor with margins free of disease is the best method of ensuring removal of CRC. The size of the tumor, its location, the extent of metastasis, the integrity of the bowel, and the condition of the patient determine which surgical procedure is performed for colorectal cancer (Table 59-1). Many regional lymph nodes are removed and examined for presence of cancer. The number of lymph nodes that contain cancer is a strong predictor of prognosis. The most common surgeries performed are colon resection (removal of the tumor and regional lymph nodes) with reanastomosis, colectomy (colon removal) with colostomy (temporary or permanent) or ileostomy/ileoanal pull-through, and abdominoperineal (AP) resection. A colostomy is the surgical creation of an opening of the colon onto the surface of the abdomen. An AP resection is performed when rectal tumors are present. The surgeon removes the sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus through combined abdominal and perineal incisions.

TABLE 59-1

SURGICAL PROCEDURES FOR COLORECTAL CANCERS IN VARIOUS LOCATIONS

For patients having a colon resection, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) via laparoscopy is commonly performed today. This procedure results in shorter hospital stays, less pain, fewer complications, and quicker recovery compared with the conventional open surgical approach.

Preoperative Care.

Reinforce the physician’s explanation of the planned surgical procedure. The patient is told as accurately as possible what anatomic and physiologic changes will occur with surgery. The location and number of incision sites and drains are also discussed.

Before evaluating the tumor and colon during surgery, the surgeon may not be able to determine whether a colostomy (or less commonly, an ileostomy) will be necessary. The patient is told that a colostomy is a possibility. If a colostomy is planned, the surgeon consults a certified wound, ostomy, continence nurse (CWOCN) or an enterostomal therapist (ET) (ostomy nurse) to recommend optimal placement of the ostomy. He or she teaches the patient about the rationale and general principles of ostomy care. In many settings, the CWOCN marks the patient’s abdomen to indicate a potential ostomy site that will decrease the risk for complications such as interference of the undergarments or a prosthesis with the ostomy appliance. Table 59-2 describes the role of the CWOCN or ET.

TABLE 59-2

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT BY THE CWOCN OR ET NURSE

| Key Points of Psychosocial Assessment |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|