M. Linda Workman

Care of Patients with Noninfectious Upper Respiratory Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

8 Prioritize nursing care needs of a patient after a nasoseptoplasty.

10 Prioritize nursing care needs of a patient with facial trauma.

11 Describe the pathophysiology and the potential complications of sleep apnea.

12 Apply knowledge of anatomy to prevent aspiration in a patient with a tracheostomy.

13 Explain the techniques for wound care and laryngectomy care.

14 Use correct technique to suction via a tracheostomy or laryngectomy tube.

15 Teach the patient and family about home management of a laryngectomy stoma or tracheostomy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Anatomic Location of Sinuses

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Clip: Stridor

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The nose, sinuses, oropharynx, larynx, and trachea are the upper airway structures. They are important for oxygenation and tissue perfusion by providing the entrance site for air. Problems of the upper airways, especially the larynx and trachea, can interfere with oxygen delivery. The upper airway structures may have specific health problems and also may be affected by other common acute and chronic disorders. Patients with upper respiratory problems are found in the community and many health care settings. The major nursing priority with disorders of the upper respiratory tract is to promote oxygenation by ensuring a patent airway.

Disorders of the Nose and Sinuses

Fracture of the Nose

Pathophysiology

Nasal fractures often result from injuries received during falls, sports activities, car crashes, or physical assaults. If the bone or cartilage is not displaced, serious complications usually do not result from the fracture and treatment may not be needed. Displacement of either the bone or cartilage, however, can cause airway obstruction or cosmetic deformity and is a potential source of infection.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Document any nasal problem, including deviation, malaligned nasal bridge, a change in nasal breathing, crackling of the skin (crepitus) on palpation, bruising, and pain. Blood or clear fluid (cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]) rarely drains from one or both nares as a result of a simple nasal fracture and, if present, indicates a more serious injury (e.g., skull fracture). CSF can be differentiated from normal nasal secretions because CSF contains glucose that will test positive with a dipstick. When CSF dries on a piece of filter paper, a yellow “halo” appears as a ring at the dried edge of the fluid. X-rays are not always useful in the diagnosis of simple nasal fractures.

Interventions

The health care provider performs a simple closed reduction (manipulation of the bones by palpation to position them in proper alignment) of the nasal fracture using local or general anesthesia within the first 24 hours after injury. After 24 hours, the fracture is more difficult to reduce because of edema and scar formation. Then reduction may be delayed for several days until edema is gone. Simple closed fractures may not need surgical intervention. Management focuses on pain relief and cold compresses to decrease swelling.

Rhinoplasty

Reduction and surgery may be needed for severe fractures or for those that do not heal properly. Rhinoplasty is a surgical reconstruction of the nose. It can be performed to repair a fractured nose and also is a common plastic surgery procedure to change the shape of the nose. The patient returns from surgery with packing in both nostrils; this packing prevents bleeding and provides support for the reconstructed nose. The gauze packing is treated with an antibiotic to reduce the risk for infection. A “moustache” dressing (or drip pad), often a folded 2 × 2 gauze pad, is usually placed under the nose (Fig. 31-1). A splint or cast may cover the nose for better alignment and protection. The nurse or patient changes the drip pad as necessary.

After surgery, observe for edema and bleeding. Check vital signs every 4 hours until the patient is discharged. The patient with uncomplicated rhinoplasty is discharged the day of surgery. Instruct him or her and the family about the routine care described below.

Instruct the patient to stay in a semi-Fowler’s position and to move slowly. Teach him or her to rest and use cool compresses on the nose, eyes, and face to help reduce swelling and bruising. If a general anesthetic was used, the patient may eat soft foods once he or she is alert and the gag reflex has returned. Urge the patient to drink at least 2500 mL/day.

To prevent bleeding, teach the patient to limit Valsalva maneuvers (e.g., forceful coughing or straining during a bowel movement), not to sniff upward or blow the nose, and not to sneeze with the mouth closed for the first few days after the packing is removed. Laxatives or stool softeners may be prescribed to ease bowel movement. Instruct the patient to avoid aspirin and other NSAIDs to prevent bleeding. Antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent infection. Recommend the use of a humidifier to prevent drying of the mucosa. Explain that edema and bruising last for weeks and that the final surgical result will be evident in 6 to 12 months.

Nasoseptoplasty

Nasoseptoplasty, or submucous resection (SMR), may be needed to straighten a deviated septum when chronic symptoms (e.g., “stuffy” nose, snoring, sinusitis) or discomfort occurs. Most adults have a slight nasal septum deviation with no symptoms. Major deviations, however, may obstruct the nasal passages or interfere with airflow and sinus drainage. The deviated section of the cartilage and bone is removed as an ambulatory surgical procedure. The amount resected depends on the deformity. Newer surgical procedures for a severely deviated septum include actual removal of part of the septal cartilage. The cartilage is then straightened separate from the body (extracorporeal) and then replaced into the nose along with sutures and struts for maintaining shape and position (Jang & Kwon, 2010). Nursing care is similar to that for a rhinoplasty.

Epistaxis

Pathophysiology

Epistaxis (nosebleed) is a common problem because of the many capillaries within the nose. Nosebleeds occur as a result of trauma, hypertension, blood dyscrasia (e.g., leukemia), inflammation, tumor, decreased humidity, nose blowing, nose picking, chronic cocaine use, and procedures such as nasogastric suctioning. Men usually are affected more often than women. Older adults tend to bleed most often from the posterior portion of the nose.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

The patient often reports that the bleeding started after sneezing or blowing the nose. Document the amount and color of the blood, and take the vital signs. Ask the patient about the number, duration, and causes of previous bleeding episodes. Record this information in the patient’s medical record.

Chart 31-1 lists the best practices for emergency care of the patient with a nosebleed. An additional intervention for use at home or in the emergency department is a special nasal plug that contains an agent to promote blood clotting (sold by HemCon). The plug expands on contact with blood and compresses mucosal blood vessels. This device can be removed in an hour.

Medical attention is needed if the nosebleed does not respond to these interventions. In such cases, the affected capillaries may be cauterized with silver nitrate or electrocautery and the nose packed. Anterior packing controls bleeding from the anterior nasal cavity.

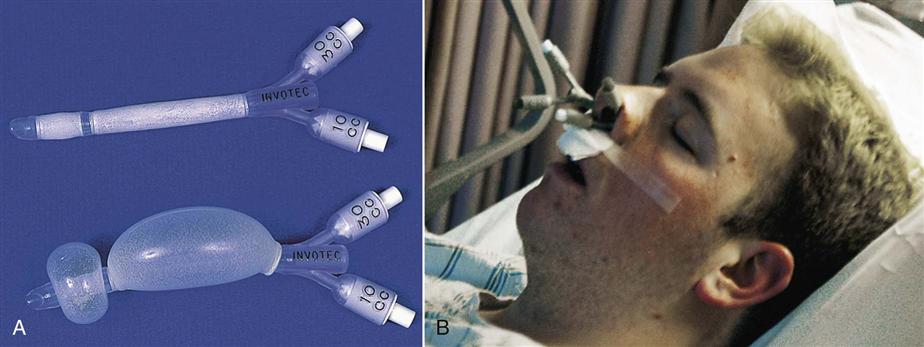

Posterior nasal bleeding is an emergency because it cannot be easily reached and the patient may lose a lot of blood quickly. Posterior packing, epistaxis catheters (nasal pressure tubes), or a gel tampon are used to stop bleeding that originates in the posterior nasal region. With packing, the health care provider positions a large gauze pack in the posterior nasal cavity above the throat, threads the attached string through the nose, and tapes it to the patient’s cheek to prevent pack movement. Epistaxis catheters look like very short (about 6 inches) urinary catheters (Fig. 31-2, A). These tubes have an exterior balloon along the tube length in addition to an anchoring balloon on the end. The tubes are inserted into both nares. The anchoring balloon is inflated first to keep the tubes in place. Then the pressure balloons are inflated carefully for both tubes at the same time to compress bleeding vessels (Fig. 31-2, B). Placement of posterior packing or pressure tubes is uncomfortable, and the airway may be obstructed if the pack slips. Most patients who have posterior nasal bleeding are hospitalized (Rushing, 2009).

Observe the patient for respiratory distress and for tolerance of the packing or tubes. Humidity, oxygen, bedrest, and antibiotics may be prescribed. Opioid drugs may be prescribed for pain. Assess patients receiving opioids at least hourly for gag and cough reflexes. Oral care and hydration are important because of mouth breathing. Use pulse oximetry to monitor for hypoxemia. The tubes or packing is usually removed after 1 to 3 days.

After the tubes or packing is removed, teach the patient and family the following interventions to use at home for comfort and safety. Petroleum jelly can be applied to the nares for lubrication and comfort. Nasal saline sprays and humidification add moisture and prevent rebleeding. Instruct the patient to avoid vigorous nose blowing, the use of aspirin or other NSAIDs, and strenuous activities such as heavy lifting for at least 1 month (Rushing, 2009).

Nasal Polyps

Nasal polyps are benign, grapelike clusters of mucous membrane and connective tissue. They often occur bilaterally and are caused by irritation to the nasal mucosa or sinuses, allergies, or infection (chronic sinusitis). Large polyps may obstruct the airway. Manifestations include obstructed nasal breathing, increased nasal discharge, and a change in voice quality.

Benign nasal polyps are managed with nasally inhaled steroids followed by surgical removal (polypectomy), with standard or laser surgery, performed under local or general anesthesia. Observe the patient for bleeding after surgery. The nostrils are usually packed with gauze for 24 hours after surgery. Polyps often recur after treatment.

Cancer of the Nose and Sinuses

Tumors of the nasal cavities and sinuses are rare and may be either benign or malignant. Malignant tumors can occur at all ages, but the peak incidence is 40 to 45 years of age in men and 60 to 65 years of age in women. Asian Americans have a higher incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer. This type of cancer is more common among people with chronic exposure to wood dusts, dusts from textiles, leather dusts, flour, nickel and chromium dust, mustard gas, and radium. Cigarette smoking along with these exposures increases the risk (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011).

The onset of sinus cancer is slow, and manifestations resemble sinusitis. Thus the patient may have advanced disease at diagnosis. Manifestations of nasal or sinus cancer include persistent nasal obstruction, drainage, bloody discharge, and pain that persists after treatment of sinusitis. Lymph node enlargement often occurs on the side with tumor mass. Tumor location is identified with x-ray, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A biopsy is performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Surgical removal of all or part of the tumor is the main treatment for nasopharyngeal cancers. It is usually combined with radiation therapy, especially intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). This type of radiation breaks up the single beam into thousands of smaller beams that allow better focus on the tumor (see Chapter 24). The specific surgery depends on tumor size, location, and degree of invasion. Problems after surgery include a change in body image or speech and altered nutrition. These problems are most common when the maxilla and floor of the nose are involved in the surgery. Patients often also have changes in taste and smell.

Provide general postoperative care (see Chapter 18), including maintaining a patent airway, monitoring for hemorrhage, providing wound care, assessing nutritional status, and performing tracheostomy care (if needed). (See Chapter 30 for tracheostomy care.) Perform careful mouth and sinus cavity care with saline irrigations using an electronic irrigation system (e.g., Waterpik, Sonicare) or a syringe. Assess the patient for pain and infection. Good nutrition is essential after surgery to promote healing. Collaborate with the dietitian to help the patient make food selections that promote healing.

Chemotherapy may be used in conjunction with surgery and radiation for some tumors. The most commonly used agents for cancer of the nose and sinuses include carboplatin, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel, and paclitaxel, although other drugs may be used depending on the features of the tumor. Chapter 24 discusses care of the patient undergoing chemotherapy.

Facial Trauma

Pathophysiology

Facial trauma is described by the specific bones (e.g., mandibular, maxillary, orbital, nasal fractures) and the side of the face involved. Mandibular (lower jaw) fractures can occur at any point on the jaw and are common facial fractures. Le Fort I is a nasoethmoid complex fracture. Le Fort II is a maxillary and nasoethmoid complex fracture. Le Fort III combines I and II plus an orbital-zygoma fracture, called “craniofacial disjunction” because the midface has no connection to the skull. The rich facial blood supply allows extensive bleeding and bruising.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The priority action to take for a patient with facial trauma is airway assessment. Manifestations of airway obstruction include stridor, shortness of breath, dyspnea, anxiety, restlessness, hypoxia, hypercarbia (elevated blood levels of carbon dioxide), decreased oxygen saturation, cyanosis, and loss of consciousness. After establishing the airway, assess the site of trauma for bleeding and possible fractures. Check for soft-tissue edema, facial asymmetry, pain, or leakage of spinal fluid through the ears or nose, indicating a temporal bone or basilar skull fracture. Assess vision and eye movement because orbital and maxillary fractures can entrap the eye. Check behind the ears (mastoid area) for extensive bruising, known as the “battle sign.” Because facial trauma can occur with spinal trauma and skull fractures, cranial computed tomography, facial series, and cervical spine x-rays are obtained.

Interventions

The priority action is to establish and maintain a patent airway. Anticipate the need for emergency intubation, tracheotomy (surgical incision into the trachea to create an airway), or cricothyroidotomy (creation of a temporary airway by making a small opening in the throat between the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage). Upon patient arrival, care focuses on establishing an airway, controlling hemorrhage, and assessing for the extent of injury. If shock is present, fluid resuscitation and identification of bleeding sites are started immediately.

Time is critical in stabilizing the patient who has head and neck trauma. Early response and treatment by special services (e.g., trauma team, maxillofacial surgeon, general surgeon, otolaryngologist, plastic surgeon, dentist) optimize the patient’s recovery.

Stabilizing the fractured segment of a jaw fracture allows the teeth to heal in proper alignment. This process involves fixed occlusion (wiring the jaws together in the mouth closed position). The patient remains in fixed occlusion for 6 to 10 weeks. Antibiotic therapy may be prescribed because of oral wound contamination. Treatment delay, tooth infection, or poor oral care may cause mandibular bone infection, which may require surgical débridement (removal of dead tissue), IV antibiotic therapy, and a longer period with the jaws in a fixed position.

More extensive jaw fractures may require open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) procedures. Compression plates and reconstruction plates with screws may be applied. Plates may be made of stainless steel, titanium, or Vitallium. If the mandibular fracture is repaired with titanium plates, teach the patient about oral care, soft-diet restrictions, and follow-up care with a dentist. These plates are permanent and do not interfere with MRI studies.

Facial fractures may be repaired with microplating surgical systems that involve bone substitutes (e.g., BoneSource). These shaping plates hold the bone fragments in place until new bone growth occurs. Bone cells grow into the bone substitute and re-matrix into a stable bone support. The plates may remain in place permanently or may be removed after healing.

Fixation methods may use resorbable devices (plates and screws) to hold tissues in place. These devices are made from a plastic-like material that retains its integrity for about 8 weeks and then slowly biodegrades. Resorbable devices are not used when the area has previously been irradiated or for patients who smoke or who have drug or alcohol dependence, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, or impaired cardiac function, all of which impair healing.

Inner maxillary fixation (IMF) is another method of securing a mandibular fracture. The bones are realigned and then wired in place with the bite closed. Nondisplaced aligned fractures can be repaired in a clinic or office using local dental anesthesia. General anesthesia is used to repair displaced or complex fractures or fractures that occur with other facial bone fractures.

After surgery, teach the patient about oral care with an irrigating device, such as a Waterpik or Sonicare. If the patient has inner maxillary fixation, teach self-management with wires in place, including a dental liquid diet. If the patient vomits, watch for aspiration because of the patient’s inability to open the jaws to allow ejection of the emesis. Teach him or her how to cut the wires if emesis occurs. Instruct the patient to keep wire cutters with him or her at all times in case this emergency arises. If the wires are cut, instruct him or her to return to the surgeon for rewiring as soon as possible to reinstitute fixation.

Nutrition is important and difficult for a patient with fractures because of oral fixation, pain, and surgery. Collaborate with the dietitian for patient teaching and support.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Pathophysiology

Sleep apnea is a breathing disruption during sleep that lasts at least 10 seconds and occurs a minimum of 5 times in an hour. Although sleep apnea can have a neurologic origin, the most common form occurs as a result of upper airway obstruction by the soft palate or tongue. Factors that contribute to sleep apnea include obesity, a large uvula, a short neck, smoking, enlarged tonsils or adenoids, and oropharyngeal edema (Berry, 2008). Men are affected more often than women, and the risk increases with age (Townsend-Roccichelli et al., 2010).

During sleep, the muscles relax and the tongue and neck structures are displaced. As a result, the upper airway is obstructed but chest movement is unimpaired. The apnea increases blood carbon dioxide levels and decreases the pH. These blood gas changes stimulate neural centers. The sleeper awakens after 10 seconds or longer of apnea and corrects the obstruction, and respiration resumes. After he or she goes back to sleep, the cycle begins again, sometimes as often as every 5 minutes (Berry, 2008).

This cyclic pattern of disrupted sleep prevents the deep sleep needed for best rest. Thus the person may have excessive daytime sleepiness, an inability to concentrate, and irritability.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Patients are often unaware that they have sleep apnea. The disorder should be suspected for any person who has persistent daytime sleepiness or reports “waking up tired,” particularly if he or she also snores heavily. Other manifestations include irritability and personality changes. Sleep apnea may be verified by family members who observe the problem when the person sleeps on his or her back. A complete health assessment should be performed when excessive daytime sleepiness is a problem.

The most accurate test for sleep apnea is polysomnography (PSG) performed during an overnight sleep study. The patient is directly observed while wearing a variety of monitoring equipment, including an electroencephalograph (EEG), an electrocardiograph (ECG), a pulse oximeter, and an electromyograph (EMG). This test determines the depth of sleep, type of sleep, respiratory effort, oxygen saturation, and muscle movement.

Interventions

A change in sleeping position or weight loss may reduce or correct mild sleep apnea. Position-fixing devices may prevent subluxation of the tongue and neck structures and reduce obstruction. Severe sleep apnea requires nonsurgical or surgical methods to prevent obstruction.

A common method to prevent airway collapse is the use of noninvasive, positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV) to hold open the upper airways. A nasal mask or full-face mask delivery system allows mechanical delivery of either bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), autotitrating positive airway pressure (APAP), or nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). With BiPAP, a machine delivers a set inspiratory positive airway pressure at the beginning of each breath. As the patient begins to exhale, the machine delivers a lower end expiratory pressure. These two pressures hold open the upper airways. With APAP, the machine adjusts continuously, resetting the pressure throughout the breathing cycle to meet the patient’s needs. Nasal CPAP delivers a set positive airway pressure continuously during each cycle of inhalation and exhalation. For any positive-pressure ventilation through a facemask during sleep, a small electric compressor is required. Proper fit of the mask over the nose and mouth or just over the nose is key to successful treatment (see Fig. 30-9 in Chapter 30). Although noisy, these methods are accepted by most patients after an adjustment period.

One drug has been approved to help manage the daytime sleepiness associated with sleep apnea. Modafinil (Attenace, Provigil) is helpful for patients who have narcolepsy (uncontrolled daytime sleep) from sleep apnea by promoting daytime wakefulness. This action does not treat the cause of sleep apnea.

Surgical intervention may involve a simple adenoidectomy, uvulectomy, or remodeling of the entire posterior oropharynx (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty [UPP]). Both conventional and laser surgeries are used for this purpose (Robinson et al., 2009). A tracheostomy may be needed for very severe sleep apnea that is not relieved by more moderate interventions.

Disorders of the Larynx

Vocal Cord Paralysis

Vocal fold (cord) paralysis may result from injury, trauma, or diseases that affect the larynx, laryngeal nerves, or vagus nerve. Prolonged intubation with an endotracheal (ET) tube may cause temporary or permanent paralysis. Paralysis may occur in patients with neurologic disorders. Damage to the vagus nerve (by chest injury), brain, or brainstem may lead to nerve dysfunction. The laryngeal nerves may be damaged from trauma or disorders that involve the chest, esophagus, or thyroid. Paralysis of both vocal cords may result from direct injury, stroke involving the brainstem, or total thyroidectomy.

Vocal fold paralysis may affect both cords or only one. When only one vocal cord is involved (most common), the airway remains patent but the voice is affected. Manifestations of open bilateral vocal cord paralysis include hoarseness; a breathy, weak voice; and aspiration of food. Bilateral closed vocal cord paralysis causes airway obstruction and is an emergency if the symptoms are severe and the patient cannot compensate. Stridor is the major manifestation.

Securing an airway is the main intervention. Place the patient in a high-Fowler’s position to aid in breathing and proper alignment of airway structures. Assess for airway obstruction.

Various surgical procedures can improve the voice. One simple procedure for open vocal cord paresis involves injecting polytef (Teflon) into the affected cord so it enlarges toward the unaffected cord. This technique improves closure during speaking and eating.

The patient with open cord paralysis is at risk for aspiration because the airway is open during swallowing. Teach him or her to hold the breath during swallowing to allow the larynx to rise, close, and push food back into the esophagus. Teach the patient to tuck the chin down and tilt the forehead forward during swallowing. Indications of aspiration include immediate coughing on swallowing of liquids or solids, a “wet”-sounding voice, and “tearing up” or watery eyes on swallowing. Chest x-rays are used to diagnose aspiration pneumonia.

Vocal Cord Nodules and Polyps

Nodules are enlarged, fibrous tissues caused by infectious processes or overuse of the voice. They often occur where the vocal cords touch during speech. People most affected are those who often speak loudly, such as teachers, coaches, sports fans, and singers.

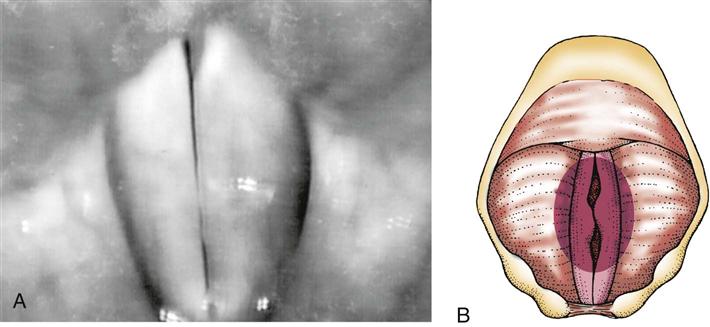

Polyps are edematous masses that occur most often in smokers and people with allergies. Vocal cysts also may occur. Nodules and polyps are painless. The main manifestation is painless hoarseness because of the loss of coordinated vocal cord closure (Fig. 31-3).

Management of cord nodules or polyps focuses on patient education. Instruct the patient about smoking cessation and the importance of voice rest. Treatment includes not speaking, especially not whispering, and avoiding heavy lifting. Stool softeners are used to avoid bearing down during elimination, which closes the glottis. Humidifying the air soothes the cords and prevents overdrying. Speech and language therapy is used to help the patient learn to reduce speech intensity and may make surgery unnecessary.

If hoarseness is not relieved by voice rest or speech and language therapy, the surgeon may remove the nodules or polyps using laryngoscopy. Laser and surgical resection are used to remove the membrane of the affected cord. If both cords are involved, one cord is usually allowed to heal before the other cord is resected. Before these ambulatory surgical procedures, teach the patient about the care techniques needed for after surgery.

After surgery, the patient must maintain complete voice rest for about 14 days to promote healing. Chart 31-2 lists methods for nonverbal communication. Teach about alternative methods of communication such as a slate, picture board, pen and paper, alphabet board, or programmable speech-generating device (Rodriguez & Rowe, 2010). Place a sign on the patient’s door, over the bed, and on the intercom system to help implement voice rest.

Laryngeal Trauma

Laryngeal trauma occurs with a crushing or direct blow injury, fracture, or injury induced by prolonged endotracheal intubation. Manifestations include difficulty breathing (dyspnea), inability to produce sound (aphonia), hoarseness, and subcutaneous emphysema (air present in the subcutaneous tissue). Bleeding from the airway (hemoptysis) may occur, depending on the location of the trauma. The health care provider performs a direct visual examination of the larynx by laryngoscopy or fiberoptic laryngoscopy to determine the extent of the injury.

Management of patients with laryngeal injuries consists of assessing the airway and monitoring vital signs (including respiratory status and pulse oximetry) every 15 to 30 minutes. Maintaining a patent airway is a priority. Apply oxygen and humidification as prescribed to maintain adequate oxygen saturation. Manifestations of respiratory difficulty include tachypnea, nasal flaring, anxiety, sternal retraction, shortness of breath, restlessness, decreased oxygen saturation, decreased level of consciousness, and stridor.

Surgical intervention is needed for lacerations of the mucous membranes, cartilage exposure, and cord paralysis. Laryngeal repair is performed as soon as possible to prevent laryngeal stenosis and to cover any exposed cartilage. An artificial airway may be needed.

Other Upper Airway Disorders

Upper Airway Obstruction

Pathophysiology

Upper airway obstruction is a life-threatening emergency in which airflow is interrupted through the nose, mouth, pharynx, or larynx. Early recognition is essential to prevent complications, including respiratory arrest. Causes of upper airway obstruction include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree