Chapter 31 Care of Patients with Noninfectious Upper Respiratory Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Supervise care delegated to licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs) or nursing assistants to patients who have risk factors for airway obstruction.

2. Act as a patient advocate for patients receiving oxygen or who have tracheostomies.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Assess the patient for risk factors for head and neck cancer.

4. Teach people how to avoid common risk factors for head and neck cancer.

5. Support the patient and family in coping with changes in breathing status and the need for a laryngectomy.

6. Use an appropriate nonverbal form of communication for a patient with a laryngectomy.

7. Perform a focused upper respiratory assessment and re-assessment to determine adequacy of oxygenation and tissue perfusion.

8. Prioritize nursing care needs of a patient after a nasoseptoplasty.

9. Recognize manifestations and care needs of a patient with an anterior nosebleed and of a patient with a posterior nosebleed.

10. Prioritize nursing care needs of a patient with facial trauma.

11. Describe the pathophysiology and the potential complications of sleep apnea.

12. Apply knowledge of anatomy to prevent aspiration in a patient with a tracheostomy.

13. Explain the techniques for wound care and laryngectomy care.

14. Use correct technique to suction via a tracheostomy or laryngectomy tube.

15. Teach the patient and family about home management of a laryngectomy stoma or tracheostomy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Anatomic Location of Sinuses

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Disorders of the Nose and Sinuses

Fracture of the Nose

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Rhinoplasty

Reduction and surgery may be needed for severe fractures or for those that do not heal properly. Rhinoplasty is a surgical reconstruction of the nose. It can be performed to repair a fractured nose and also is a common plastic surgery procedure to change the shape of the nose. The patient returns from surgery with packing in both nostrils; this packing prevents bleeding and provides support for the reconstructed nose. The gauze packing is treated with an antibiotic to reduce the risk for infection. A “moustache” dressing (or drip pad), often a folded 2 × 2 gauze pad, is usually placed under the nose (Fig. 31-1). A splint or cast may cover the nose for better alignment and protection. The nurse or patient changes the drip pad as necessary.

Action Alert

Nasoseptoplasty

Nasoseptoplasty, or submucous resection (SMR), may be needed to straighten a deviated septum when chronic symptoms (e.g., “stuffy” nose, snoring, sinusitis) or discomfort occurs. Most adults have a slight nasal septum deviation with no symptoms. Major deviations, however, may obstruct the nasal passages or interfere with airflow and sinus drainage. The deviated section of the cartilage and bone is removed as an ambulatory surgical procedure. The amount resected depends on the deformity. Newer surgical procedures for a severely deviated septum include actual removal of part of the septal cartilage. The cartilage is then straightened separate from the body (extracorporeal) and then replaced into the nose along with sutures and struts for maintaining shape and position (Jang & Kwon, 2010). Nursing care is similar to that for a rhinoplasty.

Epistaxis

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Chart 31-1 lists the best practices for emergency care of the patient with a nosebleed. An additional intervention for use at home or in the emergency department is a special nasal plug that contains an agent to promote blood clotting (sold by HemCon). The plug expands on contact with blood and compresses mucosal blood vessels. This device can be removed in an hour.

Chart 31-1 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Emergency Care of a Patient with an Anterior Nosebleed

• Maintain Standard Precautions or Body Substance Precautions.

• Position the patient upright and leaning forward to prevent blood from entering the stomach and possible aspiration.

• Reassure the patient and attempt to keep him or her quiet to reduce anxiety and blood pressure.

• Apply direct lateral pressure to the nose for 10 minutes, and apply ice or cool compresses to the nose and face if possible.

• If nasal packing is necessary, loosely pack both nares with gauze or nasal tampons.

• To prevent rebleeding from dislodging clots, instruct the patient to not blow the nose for 24 hours after the bleeding stops.

• Seek medical assistance if these measures are ineffective or if the bleeding occurs frequently.

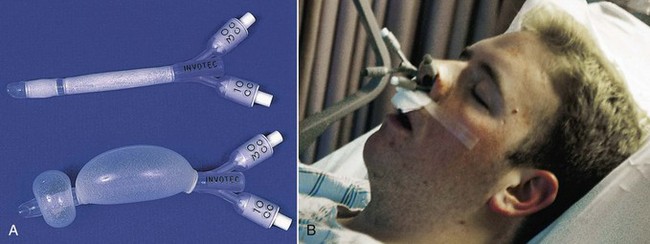

Posterior nasal bleeding is an emergency because it cannot be easily reached and the patient may lose a lot of blood quickly. Posterior packing, epistaxis catheters (nasal pressure tubes), or a gel tampon are used to stop bleeding that originates in the posterior nasal region. With packing, the health care provider positions a large gauze pack in the posterior nasal cavity above the throat, threads the attached string through the nose, and tapes it to the patient’s cheek to prevent pack movement. Epistaxis catheters look like very short (about 6 inches) urinary catheters (Fig. 31-2, A). These tubes have an exterior balloon along the tube length in addition to an anchoring balloon on the end. The tubes are inserted into both nares. The anchoring balloon is inflated first to keep the tubes in place. Then the pressure balloons are inflated carefully for both tubes at the same time to compress bleeding vessels (Fig. 31-2, B). Placement of posterior packing or pressure tubes is uncomfortable, and the airway may be obstructed if the pack slips. Most patients who have posterior nasal bleeding are hospitalized (Rushing, 2009).

After the tubes or packing is removed, teach the patient and family the following interventions to use at home for comfort and safety. Petroleum jelly can be applied to the nares for lubrication and comfort. Nasal saline sprays and humidification add moisture and prevent rebleeding. Instruct the patient to avoid vigorous nose blowing, the use of aspirin or other NSAIDs, and strenuous activities such as heavy lifting for at least 1 month (Rushing, 2009).

Cancer of the Nose and Sinuses

Tumors of the nasal cavities and sinuses are rare and may be either benign or malignant. Malignant tumors can occur at all ages, but the peak incidence is 40 to 45 years of age in men and 60 to 65 years of age in women. Asian Americans have a higher incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer. This type of cancer is more common among people with chronic exposure to wood dusts, dusts from textiles, leather dusts, flour, nickel and chromium dust, mustard gas, and radium. Cigarette smoking along with these exposures increases the risk (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011).

Surgical removal of all or part of the tumor is the main treatment for nasopharyngeal cancers. It is usually combined with radiation therapy, especially intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). This type of radiation breaks up the single beam into thousands of smaller beams that allow better focus on the tumor (see Chapter 24). The specific surgery depends on tumor size, location, and degree of invasion. Problems after surgery include a change in body image or speech and altered nutrition. These problems are most common when the maxilla and floor of the nose are involved in the surgery. Patients often also have changes in taste and smell.

Provide general postoperative care (see Chapter 18), including maintaining a patent airway, monitoring for hemorrhage, providing wound care, assessing nutritional status, and performing tracheostomy care (if needed). (See Chapter 30 for tracheostomy care.) Perform careful mouth and sinus cavity care with saline irrigations using an electronic irrigation system (e.g., Waterpik, Sonicare) or a syringe. Assess the patient for pain and infection. Good nutrition is essential after surgery to promote healing. Collaborate with the dietitian to help the patient make food selections that promote healing.

Chemotherapy may be used in conjunction with surgery and radiation for some tumors. The most commonly used agents for cancer of the nose and sinuses include carboplatin, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel, and paclitaxel, although other drugs may be used depending on the features of the tumor. Chapter 24 discusses care of the patient undergoing chemotherapy.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Pathophysiology

Sleep apnea is a breathing disruption during sleep that lasts at least 10 seconds and occurs a minimum of 5 times in an hour. Although sleep apnea can have a neurologic origin, the most common form occurs as a result of upper airway obstruction by the soft palate or tongue. Factors that contribute to sleep apnea include obesity, a large uvula, a short neck, smoking, enlarged tonsils or adenoids, and oropharyngeal edema (Berry, 2008). Men are affected more often than women, and the risk increases with age (Townsend-Roccichelli et al., 2010).

During sleep, the muscles relax and the tongue and neck structures are displaced. As a result, the upper airway is obstructed but chest movement is unimpaired. The apnea increases blood carbon dioxide levels and decreases the pH. These blood gas changes stimulate neural centers. The sleeper awakens after 10 seconds or longer of apnea and corrects the obstruction, and respiration resumes. After he or she goes back to sleep, the cycle begins again, sometimes as often as every 5 minutes (Berry, 2008).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Interventions

A common method to prevent airway collapse is the use of noninvasive, positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV) to hold open the upper airways. A nasal mask or full-face mask delivery system allows mechanical delivery of either bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), autotitrating positive airway pressure (APAP), or nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). With BiPAP, a machine delivers a set inspiratory positive airway pressure at the beginning of each breath. As the patient begins to exhale, the machine delivers a lower end expiratory pressure. These two pressures hold open the upper airways. With APAP, the machine adjusts continuously, resetting the pressure throughout the breathing cycle to meet the patient’s needs. Nasal CPAP delivers a set positive airway pressure continuously during each cycle of inhalation and exhalation. For any positive-pressure ventilation through a facemask during sleep, a small electric compressor is required. Proper fit of the mask over the nose and mouth or just over the nose is key to successful treatment (see Fig. 30-9 in Chapter 30). Although noisy, these methods are accepted by most patients after an adjustment period.

Surgical intervention may involve a simple adenoidectomy, uvulectomy, or remodeling of the entire posterior oropharynx (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty [UPP]). Both conventional and laser surgeries are used for this purpose (Robinson et al., 2009). A tracheostomy may be needed for very severe sleep apnea that is not relieved by more moderate interventions.

Disorders of the Larynx

Vocal Cord Nodules and Polyps

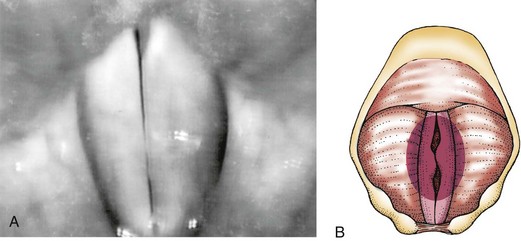

Polyps are edematous masses that occur most often in smokers and people with allergies. Vocal cysts also may occur. Nodules and polyps are painless. The main manifestation is painless hoarseness because of the loss of coordinated vocal cord closure (Fig. 31-3).

After surgery, the patient must maintain complete voice rest for about 14 days to promote healing. Chart 31-2 lists methods for nonverbal communication. Teach about alternative methods of communication such as a slate, picture board, pen and paper, alphabet board, or programmable speech-generating device (Rodriguez & Rowe, 2010). Place a sign on the patient’s door, over the bed, and on the intercom system to help implement voice rest.

Chart 31-2 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Communicating with a Patient Who Is Unable to Speak

• Assess the patient’s reading skills and cognition.

• Determine in what language (languages) the patient is most fluent.

• Collaborate with a speech and language pathologist.

• If the patient requires vision-enhancing devices or hearing-enhancing devices, be sure these are available and in use.

• Provide the patient with a variety of techniques to practice before verbal skills are lost to determine with which one(s) the patient feels most comfortable. These may include:

• Reinforce to the patient the technique for esophageal speech presented by the speech and language pathologist, and provide the time for practice.

• Use a normal tone of voice to talk with the patient (unless hearing is a pre-existing problem, a change in the ability to speak does not interfere with the patient’s ability to hear).

• Ensure that the call-light board at the nurses’ station indicates a non-speaking patient.

• Teach the patient to make noise to indicate immediate attention is needed at the bedside when he or she signals by call light. Such noises can include tapping the siderail with a spoon, making clicking noises with the tongue, using a bell, or working a noisemaker. Be sure that whatever method is selected is listed on the call-light board.

• When face-to-face with the patient:

• If writing is selected as the method to communicate, assess whether the patient is right-handed or left-handed and ensure appropriate writing materials are within reach. Use the other arm for IV placement.

• Ensure the preferred method of communication is documented in the patient record and is communicated to all care providers.

• Encourage the family to work with the patient in the use of the selected method.

• Provide praise and encouragement.

• Do not avoid talking with the patient.

Other Upper Airway Disorders

Upper Airway Obstruction

Pathophysiology

• Tongue edema (surgery, trauma, angioedema as an allergic response to a drug)

• Tongue occlusion (e.g., loss of gag reflex, loss of muscle tone, unconsciousness, coma)

• Peritonsillar and pharyngeal abscess

• Facial, tracheal, or laryngeal trauma

• Burns of the head or neck area

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree