Chapter 53 Care of Patients with Musculoskeletal Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Coordinate with health care team members when planning and providing care for patients with musculoskeletal problems.

2. Teach the patient and family about home safety when the patient has a metabolic bone problem such as osteoporosis.

3. Identify community resources for patients with musculoskeletal problems that impair mobility.

4. Apply principles of infection control for patients with osteomyelitis, including Contact Precautions if needed.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

5. Develop a teaching plan for all age-groups about ways to decrease the risk for osteoporosis.

6. Perform health risk assessments for people at risk for osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

7. Assess the genetic risk for patients who have parents with muscular dystrophy.

8. Refer patients with genetic-associated diseases for genetic counseling and testing.

9. Assess the patient’s and family’s responses to a bone cancer diagnosis and treatment options.

10. Evaluate patient’s and family’s coping strategies and fears related to grief and loss before and after bone cancer surgery.

11. Educate the patient and family about common drugs used for bone diseases, such as calcium supplements and bisphosphonates.

12. Compare and contrast osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

13. Identify key features of Paget’s disease of the bone.

14. Differentiate acute and chronic osteomyelitis.

15. Prioritize care for patients with osteomyelitis.

16. Identify collaborative management options for treating patients with primary and metastatic bone cancer.

17. Describe common disorders of the foot, including hallux valgus and plantar fasciitis, that can affect mobility.

18. Explain the role of the nurse when caring for an adult patient with muscular dystrophy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Musculoskeletal disorders include metabolic bone diseases, such as osteoporosis and Paget’s disease, bone tumors, and a variety of deformities and syndromes. Older adults are at the greatest risk for most of these problems, although primary bone cancer is most often found in adolescents and young adults. As technologic advances occur and patients survive longer with primary cancers, metastatic lesions have become more prevalent among older adults. Almost all musculoskeletal health problems can cause the patient to have difficulty meeting the human need of mobility. This chapter focuses on selected disorders not covered in Chapter 20 on arthritis and other connective tissue diseases.

Metabolic Bone Diseases

Osteoporosis

Pathophysiology

Osteoporosis is a chronic metabolic disease in which bone loss causes decreased density and possible fracture. It is often referred to as a “silent disease” because the first sign of osteoporosis in most people follows some kind of a fracture. The spine, hip, and wrist are most often at risk, although any bone can fracture (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010).

Osteoporosis is a major health problem in the world. The estimated cost for osteoporosis-related health care alone in the United States is more than $18 billion each year with continual cost increases each year. By 2040, that number is expected to double or triple (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010).

Standards for the diagnosis of osteoporosis are based on BMD testing that provides a T-score for the patient. A T-score represents the number of standard deviations above or below the average BMD for young, healthy adults. Osteopenia is present when the T-score is at −1 and above −2.5. Osteoporosis is diagnosed in a person who has a T-score at or lower than −2.5. Medicare reimburses for BMD testing every 2 years in people ages 65 years and older who (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010):

• Have vertebral abnormalities

• Receive long-term steroid therapy

• Have primary hyperparathyroidism

Osteoporosis can be classified as generalized or regional. Generalized osteoporosis involves many structures in the skeleton and is further divided into two categories, primary and secondary. Primary osteoporosis is more common and occurs in postmenopausal women and in men in their seventh or eighth decade of life. Even though men do not experience the rapid bone loss that postmenopausal women have, they do have decreasing levels of testosterone (which builds bone) and altered ability to absorb calcium. This results in a slower loss of bone mass in men, especially those older than 75 years. Secondary osteoporosis may result from other medical conditions, such as hyperparathyroidism; long-term drug therapy, such as with corticosteroids; or prolonged immobility, such as that seen with spinal cord injury (Table 53-1). Treatment of the secondary type is directed toward the cause of the osteoporosis when possible.

TABLE 53-1 CAUSES OF SECONDARY OSTEOPOROSIS

AIDS, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immune deficiency virus.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Primary osteoporosis is caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Chart 53-1 lists the major factors that contribute to the development of this disease.

Chart 53-1 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Assessing Risk Factors for Primary Osteoporosis

Genetic/Genomic Considerations

The genetic and immune factors that cause osteoporosis are very complex. Strong evidence demonstrates that genetics is a significant factor, with a heritability of 50% to 90% (Chang et al., 2010). Many genetic changes have been identified as possible causative factors, but there is no agreement about which ones are most important or constant in all patients. For example, changes in the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene and calcitonin receptor (CTR) gene have been found in some patients with the disease. Receptors are essential for the uptake and use of these substances by the cells.

Hormones, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins, and other substances in the body help control osteoclasts in a very complex pathway. The recent identification of the importance of the cytokine receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), its receptor RANK, and its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG) has helped researchers understand more about the activity of osteoclasts in metabolic bone disease. Disruptions in the RANKL, RANK, and OPG system can lead to increased osteoclast activity in which bone is rapidly broken down (McCance et al., 2010).

Men also develop osteoporosis after the age of 50 because their testosterone levels decrease. Testosterone is the major sex hormone that builds bone tissue. Men are often underdiagnosed, even when they become older adults. A recent study of almost 1200 men in a VA rehabilitation center showed that screening for osteoporosis had not been conducted. As a result of bone mineral density screening, the researchers found 33 study patients who had osteoporosis and were at high risk for fractures, especially of the hip. Those who were diagnosed with the disease were the oldest patients who had a lower body mass index and weight (Swislocki et al., 2010).

Calcium loss occurs at a more rapid rate when phosphorus intake is high. (Chapter 13 describes the usual relationship between calcium and phosphorus in the body.) People who drink large amounts of carbonated beverages each day (over 40 ounces) are at high risk for calcium loss and subsequent osteoporosis, regardless of age or gender.

Incidence/Prevalence

Osteoporosis is a potential health problem for more than 44 million Americans. About 10 million people in the United States have the disease, and about 34 million people 50 years of age and older have osteopenia and are at risk for development of osteoporosis. Women remain the largest group affected by osteoporosis, although men, especially those older than 75 years, also have the disease. After the age of 50, men are at increased risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic-related fractures (Voda, 2009b).

People of all ethnic and racial backgrounds are at some degree of risk, but white, thin women are likely to get primary osteoporosis at an earlier age (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010).

Nursing home residents fall 11 times more often than their community-dwelling counterparts (Parikh et al., 2009). Yet, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) do not routinely screen residents for osteoporosis. A national study by Gloth and Simonson (2008) reported the results of osteoporosis screening for more than 34,000 SNF residents in 26 states. Over 42% of residents were categorized as having a high risk for osteoporosis and associated fractures (see the Evidence-Based Practice box on p. 1122).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) specify the need to reduce risk for harm to patients resulting from falls. People with osteoporosis are at an increased risk for fracture if a fall occurs. The World Health Organization (WHO) Fracture Risk Algorithm (FRAX) is often used to determine the patient’s risk for fractures associated with bone loss. Chapter 3 discusses falls in older adults in more detail.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

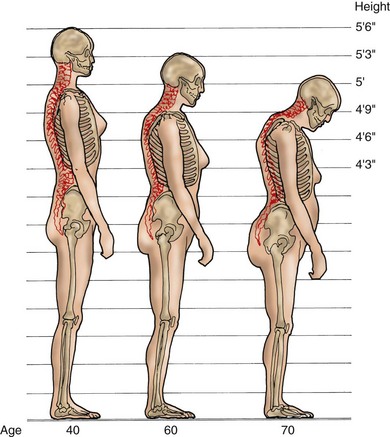

When performing a musculoskeletal assessment, inspect and palpate the vertebral column. The classic “dowager’s hump,” or kyphosis of the dorsal spine, is often present (Fig. 53-1). The patient may state that he or she has gotten shorter, perhaps as much as 2 to 3 inches (5 to 7.5 cm) within the previous 20 years. Take or delegate height and weight measurements, and compare with previous measurements if they are available.

Back pain accompanied by tenderness and voluntary restriction of spinal movement suggests one or more compression vertebral fractures, the most common type of osteoporotic fracture. Movement restriction and spinal deformity may result in constipation, abdominal distention, reflux esophagitis, and respiratory compromise in severe cases. The most likely area for spinal fracture is between T8 and L3. This problem is discussed in more detail in Chapter 54.

Laboratory Assessment

There are no definitive laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of primary osteoporosis, although a number of biochemical markers can provide information about bone resorption and formation activity. These biochemical markers are sensitive to bone changes and can be used to monitor effectiveness of treatment for osteoporosis. Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP) is found in the cell membrane of the osteoblast and indicates bone formation status. Osteocalcin is a protein substance in bone and increases during bone resorption activity. Pyridinium (PYD) cross-links are released into circulation during bone resorption. N-teleopeptide (NTX) and C-teleopeptide (CTX) are proteins released when bone is broken down. Some laboratories require a 24-hour urine collection for testing, whereas others use a double-voided specimen. Some markers, like NTX and CTX, can also be measured in the blood using immunoassay techniques. Increased levels of any of these markers indicate a risk for osteoporosis. Increased levels are found in patients with osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, and bone tumors (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Imaging Assessment

A peripheral DXA (pDXA) scan assesses BMD of the heel, forearm, or finger. It is often used for large-scale screening purposes. For example, Gloth and Simonson (2008) reported a large-scale heel BMD study for screening over 34,000 skilled nursing facility residents. The pDXA is also commonly used for screening at community health fairs and women’s health centers.

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) can also measure bone density, using either a central or peripheral technique. This procedure analyzes trabecular and cortical bone separately and is especially sensitive to changes in the vertebral column. The test is more expensive than the DXA scan and exposes the patient to more radiation; however, it is a safe screening test (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010).

Peripheral quantitative ultrasound (pQUS) is an effective and low-cost peripheral screening tool that can detect osteoporosis and predict risk for hip fracture. The heel, tibia, and patella are most commonly tested. The procedure requires no special preparation, is quick, and has no radiation exposure or specific follow-up care (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends that men older than 70 years have the pQUS as a screening tool for the disease.

Planning and Implementation

Interventions

Nutrition Therapy

A variety of nutrients are needed to maintain bone health. The promotion of a single nutrient will not prevent or treat osteoporosis. Help the patient develop a nutritional plan that is most beneficial in maintaining bone health; the plan should emphasize fruits and vegetables, low-fat dairy and protein sources, increased fiber, and moderation in alcohol and caffeine (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010).

Lifestyle Changes

Hospitals and long-term care facilities have risk management programs to assess for the risk for falls. For those patients at high risk, communicate this information to other members of the health care team, using colored armbands or other easy-to-recognize methods (National Patient Safety Goals). Chapter 3 discusses fall prevention in health care agencies and at home in more detail.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Drug Therapy

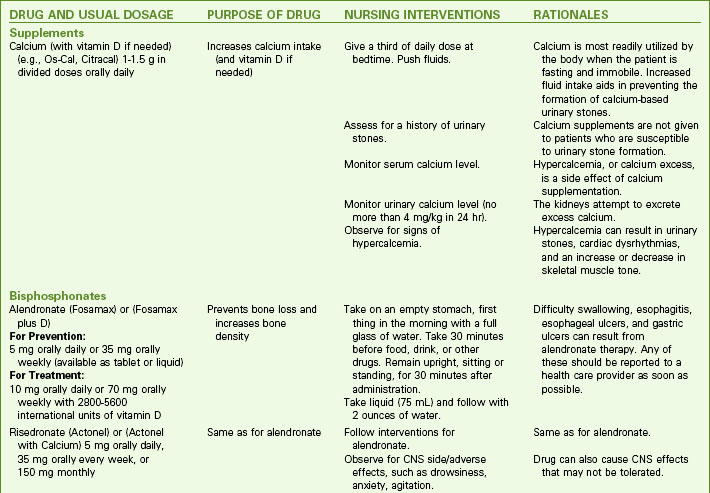

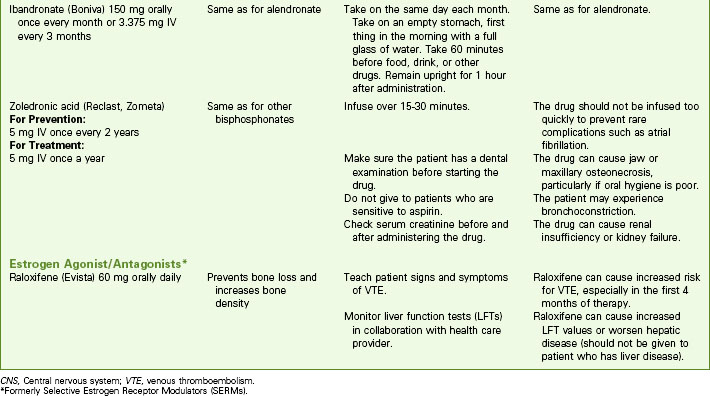

The health care provider may prescribe calcium and vitamin D supplements, bisphosphonates, or estrogen agonist/antagonists (formerly called selective estrogen receptor modulators), or a combination of several drugs to treat or prevent osteoporosis (Chart 53-2). Estrogen and combination hormone therapy are not used solely for osteoporosis prevention or management because they can increase other health risks such as breast cancer and myocardial infarction (Woman’s Health Initiative, 2005).

Calcium and Vitamin D

Remind patients to take these supplements under the supervision of a health care provider. Hypercalcemia (excess serum calcium) can cause serious damage to the urinary system and other body systems. Teach patients to drink plenty of fluids to prevent urinary or renal calculi (stones). Chapter 13 describes the clinical manifestations of hypercalcemia.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates (BPs) slow bone resorption by binding with crystal elements in bone, especially spongy, trabecular bone tissue. They are the most common drugs used for osteoporosis, but some are also approved for Paget’s disease and hypercalcemia related to cancer. Three FDA-approved BPs—alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), and risedronate (Actonel)—are commonly used for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010). These drugs are available as oral preparations, with ibandronate (Boniva) also available as an IV preparation.

Drug Alert

Drug Alert

The most recent additions to the bisphosphonates are IV zoledronic acid (Reclast) and IV pamidronate (Aredia). For management of osteoporosis, Reclast is needed only once a year and Aredia is given every 3 to 6 months. Both drugs have been linked to a complication called jaw osteonecrosis (jaw bone death) in which infection and necrosis of the mandible or maxilla occur (Lee, 2009). The incidence of this serious problem is low but can be a complication of this infusion therapy.

Other Agents

Parathyroid hormone is prepared as teriparatide under the brand name Forteo and is a bone-building agent approved for treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with high risk for fracture. Teach patients to self-administer Forteo as a daily subcutaneous injection. This drug stimulates new bone formation, thus increasing BMD. Reduced risk for fracture in the spine, hip, and wrist has been reported in women, and reduced risk for hip fracture has been reported in men. Patients may experience dizziness or leg cramping as side effects of Forteo (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2010). Teach the patient to lie down if these problems occur and notify the health care provider as soon as possible.

Patient-Centered Care; Evidence-Based Practice

1. What risk factors does this patient have for osteopenia and osteoporosis?

2. What health teaching might this patient need? How can you help her plan time for increasing her physical activity level? What does current evidence show that supports your answer?

3. What actions will you take before starting her Reclast?

4. How fast will you administer the drug, and what method will you use?

Community-Based Care

Patients with osteoporosis are usually managed at home. Osteoporosis disease-management programs managed by nurse practitioners have helped diagnose and treat the disease. Greene and Dell (2010) reported that over a 6-year period, a large osteoporosis disease-management program resulted in a 263% increase in the number of DXA scans done each year, a 153% increase in the number of patients treated with drug therapy, and a 38.1% decrease in the expected hip fracture rate.

The patient with osteoporosis who has one or more fractures may be discharged to the home setting. In some instances, though, the patient is transferred to a long-term care facility for rehabilitation or permanent residence when support systems are not available. Collaborate with case managers or discharge planners to assist in preparing patients and their families for placement in long-term care facilities. Chapter 54 discusses continuing care for patients who have fractures.

Refer patients to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (www.nof.org) in the United States to provide information to patients and health care professionals regarding the disease and its treatment. The Osteoporosis Society of Canada (www.osteoporosis.ca) has similar services. Large hospitals often have osteoporosis specialty clinics and support groups for patients with osteoporosis.

Osteomalacia

Pathophysiology

Osteomalacia is frequently confused with osteoporosis because of similar characteristics shared by the two disease processes. Table 53-2 compares and contrasts osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

TABLE 53-2 DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF OSTEOPOROSIS AND OSTEOMALACIA

| CHARACTERISTIC | OSTEOPOROSIS | OSTEOMALACIA |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Decreased bone mass | Demineralized bone |

| Pathophysiology | Lack of calcium | Lack of vitamin D |

| Radiographic findings | Osteopenia, fractures | Pseudofractures, Looser’s zones, fractures |

| Calcium level | Low or normal | Low or normal |

| Phosphate level | Normal | Low or normal |

| Parathyroid hormone | Normal | High or normal |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Normal | High |

In addition to primary disease related to lack of sunlight exposure or dietary intake, vitamin D deficiency caused by various health problems may result in osteomalacia (Table 53-3). Malabsorption of vitamin D from the small bowel is a common complication of partial or total gastrectomy and bypass or resection surgery of the small intestine. Disease of the small bowel, such as Crohn’s disease, may cause decreased vitamin and mineral absorption.

TABLE 53-3 CAUSES OF OSTEOMALACIA