Chapter 61 Care of Patients with Liver Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Describe the need to collaborate with health care team members to provide care for patients with liver problems.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Identify community resources for patients with chronic liver disease.

3. Identify risk factors for cirrhosis and hepatitis.

4. Develop a health teaching plan for patients and families to prevent hepatitis and its spread to others.

5. Develop a health teaching plan for patients and families to prevent or slow the progress of alcohol-induced cirrhosis.

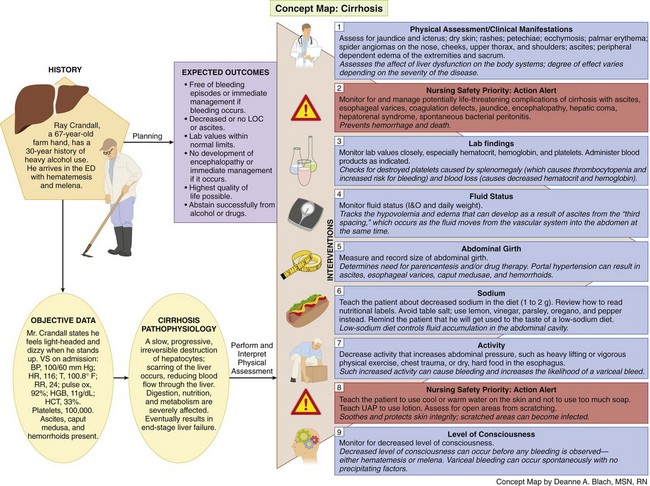

7. Explain the pathophysiology and complications associated with cirrhosis of the liver.

8. Interpret laboratory test findings commonly seen in patients with cirrhosis.

9. Analyze assessment data from patients with cirrhosis to determine priority patient problems.

10. Develop a collaborative plan of care for the patient with late-stage cirrhosis.

11. Describe the role of the nurse in monitoring for and managing potentially life-threatening complications of cirrhosis.

12. Identify emergency interventions for the patient with bleeding esophageal varices.

13. Explain the role of the nurse when assisting with a paracentesis procedure.

14. Compare and contrast the transmission of hepatitis viral infections.

15. Explain ways in which each type of hepatitis can be prevented.

16. Identify potentially life-threatening complications of liver trauma.

17. Describe treatment options for patients with cancer of the liver.

18. Describe the common complications that result from liver transplantation.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is extensive, irreversible scarring of the liver, usually caused by a chronic reaction to hepatic inflammation and necrosis. The disease typically develops slowly and has a progressive, prolonged, destructive course resulting in end-stage liver disease. The most common causes for cirrhosis in the United States are hepatitis C, alcoholism, and biliary obstruction. Worldwide, hepatitis B and hepatitis D are the leading causes. Without liver transplantation, cirrhosis is usually fatal (Kelso, 2008).

Pathophysiology

Cirrhosis is characterized by widespread fibrotic (scarred) bands of connective tissue that change the liver’s normal makeup. Inflammation caused by either toxins or disease results in extensive degeneration and destruction of hepatocytes (liver cells). As cirrhosis develops, the tissue becomes nodular. These nodules can block bile ducts and normal blood flow throughout the liver. Impairments in blood and lymph flow result from compression caused by excessive fibrous tissue. In early disease, the liver is usually enlarged, firm, and hard. As the pathologic process continues, the liver shrinks in size, resulting in decreased liver function, which can occur in weeks to years. Some patients with cirrhosis have no symptoms until serious complications occur. The impaired liver function results in elevated serum liver enzymes (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Cirrhosis of the liver can be divided into several common types, depending on the cause of the disease (McCance et al., 2010):

• Postnecrotic cirrhosis (caused by viral hepatitis [especially hepatitis C] and certain drugs or other toxins)

• Laennec’s or alcoholic cirrhosis (caused by chronic alcoholism)

• Biliary cirrhosis (also called cholestatic; caused by chronic biliary obstruction or autoimmune disease)

Complications of Cirrhosis

Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension, a persistent increase in pressure within the portal vein greater than 5 mm Hg, is a major complication of cirrhosis (Minano & Garcia-Tsao, 2010). It results from increased resistance to or obstruction (blockage) of the flow of blood through the portal vein and its branches. The blood meets resistance to flow and seeks collateral (alternative) venous channels around the high-pressure area.

Ascites and Esophageal Varices

Ascites is the collection of free fluid within the peritoneal cavity caused by increased hydrostatic pressure from portal hypertension (McCance et al., 2010). The collection of plasma protein in the peritoneal fluid reduces the amount of circulating plasma protein in the blood. When this decrease is combined with the inability of the liver to produce albumin because of impaired liver cell functioning, the serum colloid osmotic pressure is decreased in the circulatory system. The result is a fluid shift from the vascular system into the abdomen, a form of “third spacing.” As a result, the patient may have hypovolemia and edema at the same time.

Biliary Obstruction

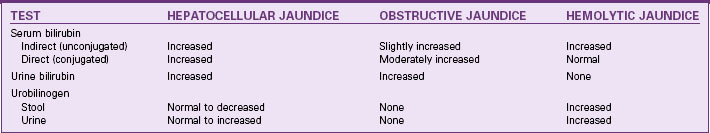

Jaundice (yellowish coloration of the skin) in patients with cirrhosis is caused by one of two mechanisms: hepatocellular disease or intrahepatic obstruction (Table 61-1). Hepatocellular jaundice develops because the liver cells cannot effectively excrete bilirubin. This decreased excretion results in excessive circulating bilirubin levels. Intrahepatic obstructive jaundice results from edema, fibrosis, or scarring of the hepatic bile channels and bile ducts, which interferes with normal bile and bilirubin excretion. Patients with jaundice often report pruritus (itching).

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy may develop slowly in patients with chronic liver disease and go undetected until the late stages. Symptoms develop rapidly in acute liver dysfunction. Four stages of development have been identified: prodromal, impending, stuporous, and comatose (Table 61-2). The patient’s symptoms may gradually progress to coma or fluctuate among the four stages.

TABLE 61-2 STAGES OF PORTAL-SYSTEMIC ENCEPHALOPATHY

| Stage I Prodromal | Stage III Stuporous |

| Stage IV Comatose | |

| Stage II Impending | |

The exact mechanisms causing hepatic encephalopathy are not clearly understood but probably are the result of the shunting of portal venous blood into the central circulation so that the liver is bypassed. As a result, substances absorbed by the intestine are not broken down or detoxified and may lead to metabolic abnormalities, such as elevated serum ammonia and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Kelso, 2008). Elevated serum ammonia results from the inability of the liver to detoxify protein by-products and is common in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. However, it is not a clear indicator of the presence of encephalopathy. Some patients may have major impairment without high elevations of serum ammonia, and elevations of ammonia can occur without evidence of encephalopathy.

Factors that may lead to hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis include:

• Hypovolemia (decreased fluid volume)

• Hypokalemia (decreased serum potassium)

• GI bleeding (causes a large protein load in the intestines)

• Drugs (e.g., hypnotics, opioids, sedatives, analgesics, diuretics, illicit drugs)

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Biliary cirrhosis occurs as a result of obstruction of the bile duct, usually from gallbladder disease or an autoimmune form of the disease called primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). Patients with PBC typically have a genetic predisposition to the disease and a positive antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) (Lindor et al., 2009). Table 61-3 summarizes known causes of liver cirrhosis.

TABLE 61-3 COMMON CAUSES OF CIRRHOSIS

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Obtain data from patients with suspected cirrhosis, including age, gender, and employment history, especially history of exposure to alcohol, drugs (prescribed and illicit), and chemical toxins. Keep in mind that all exposures are important regardless of how long ago they occurred. Determine whether there has ever been a needle stick injury. Sexual history and orientation may be important in determining an infectious cause for liver disease, because men having sex with men (MSM) are at high risk for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. People with hepatitis can develop cirrhosis (American Liver Foundation, 2011).

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

• Significant change in weight

• GI symptoms, such as anorexia and vomiting

• Abdominal pain and liver tenderness (both of which may be ignored by the patient)

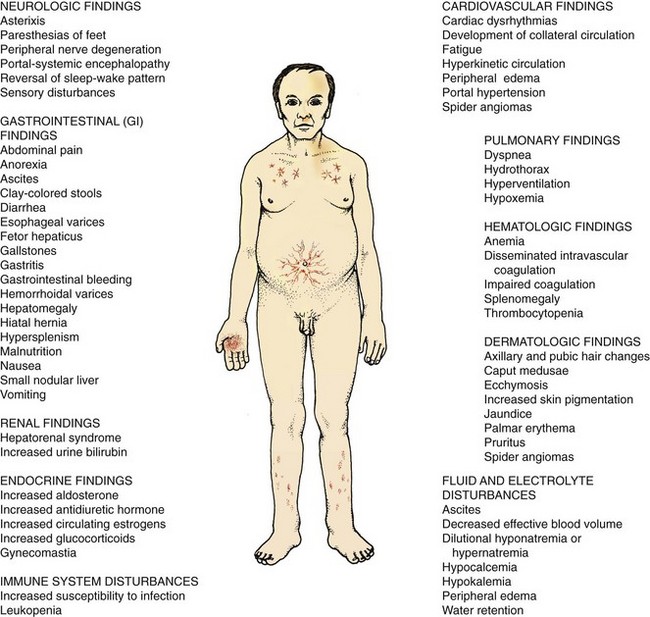

Thoroughly assess the patient with liver dysfunction or failure because it affects every body system (Fig. 61-1). The clinical picture and course vary from patient to patient depending on the severity of the disease. Assess for:

• Obvious yellowing of the skin (jaundice) and sclerae (icterus)

• Purpuric lesions, such as petechiae (round, pinpoint, red-purple lesions) or ecchymosis (large purple, blue, or yellow bruises)

• Warm and bright red palms of the hands (palmar erythema)

• Vascular lesions with a red center and radiating branches, known as “spider angiomas” (telangiectases, spider nevi, or vascular spiders), on the nose, cheeks, upper thorax, and shoulders

• Peripheral dependent edema of the extremities and sacrum

• Sicca syndrome (in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis [PBC]) (Lindor et al., 2009)

• Osteoporosis (especially in patients with PBC) (Lindor et al., 2009)

• Vitamin deficiency (especially fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K)

Abdominal Assessment

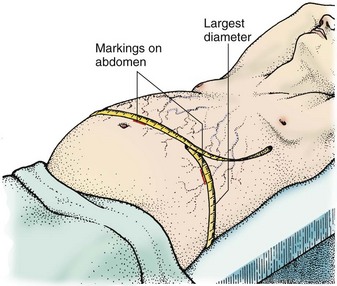

Measure the patient’s abdominal girth to evaluate the progression of ascites (Fig. 61-2). To measure abdominal girth, the patient lies flat while the nurse or other examiner pulls a tape measure around the largest diameter (usually over the umbilicus) of the abdomen. The girth is measured at the end of exhalation. Mark the abdominal skin and flanks to ensure the same tape measure placement on subsequent readings. Taking daily weights, however, is the most reliable indicator of fluid retention.

Laboratory Assessment

Laboratory study abnormalities are common in patients with liver disease (Table 61-4). Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may be elevated because these enzymes are released into the blood during hepatic inflammation. However, as the liver deteriorates, the hepatocytes may be unable to create an inflammatory response and the AST and ALT may be normal. ALT levels are more specific to the liver whereas AST can be found in muscle, kidney, brain, and heart. An AST/ALT ratio greater than 2 is usually found in alcoholic liver disease.

TABLE 61-4 ASSESSMENT OF ABNORMAL LABORATORY FINDINGS IN LIVER DISEASE

| ABNORMAL FINDING | SIGNIFICANCE |

|---|---|

| Serum Enzymes | |

| Elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | Hepatic cell destruction, hepatitis (most specific indicator) |

| Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | Hepatic cell destruction, hepatitis |

| Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | Hepatic cell destruction |

| Elevated serum alkaline phosphatase | Obstructive jaundice, hepatic metastasis |

| Bilirubin | |

| Elevated serum total bilirubin | Hepatic cell disease |

| Elevated serum direct conjugated bilirubin | Hepatitis, liver metastasis |

| Elevated serum indirect unconjugated bilirubin | Cirrhosis |

| Elevated urine bilirubin | Hepatocellular obstruction, viral or toxic liver disease |

| Elevated urine urobilinogen | Hepatic dysfunction |

| Decreased fecal urobilinogen | Obstructive liver disease |

| Serum Proteins | |

| Increased serum total protein | Acute liver disease |

| Decreased serum total protein | Chronic liver disease |

| Decreased serum albumin | Severe liver disease |

| Elevated serum globulin | Immune response to liver disease |

| Other Tests | |

| Elevated serum ammonia | Advanced liver disease or portal-systemic encephalopathy (PSE) |

| Prolonged prothrombin time (PT) or international normalized ratio (INR) | Hepatic cell damage and decreased synthesis of prothrombin |

Increased alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels are caused by biliary obstruction and therefore may increase in patients with cirrhosis (Kelso, 2008). However, alkaline phosphatase also increases when bone disease, such as osteoporosis, is present. Total serum bilirubin levels also rise. Indirect bilirubin levels increase in patients with cirrhosis because of the inability of the failing liver to excrete bilirubin. Therefore bilirubin is present in the urine (urobilinogen) in increased amounts. Fecal urobilinogen concentration is decreased in patients with biliary tract obstruction. These patients have light- or clay-colored stools.

Total serum protein and albumin levels are decreased in patients with severe or chronic liver disease as a result of decreased synthesis by the liver (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). Loss of osmotic “pull” proteins like albumin promotes the movement of intravascular fluid into the interstitial tissues (e.g., ascites). Prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) is prolonged because the liver decreases the production of prothrombin. The platelet count is low, resulting in a characteristic thrombocytopenia of cirrhosis. Anemia may be reflected by decreased red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin, and hematocrit values. The white blood cell (WBC) count may also be decreased. Ammonia levels are usually elevated in patients with advanced liver disease. Serum creatinine may be elevated in patients with deteriorating kidney function. Dilutional hyponatremia (low serum sodium) may occur in patients with ascites.

Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, an autoimmune disease, usually have high disease-specific AMA and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titers and elevated levels of immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Lindor et al., 2009).

Other Diagnostic Assessment

The physician may perform an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to directly visualize the upper GI tract and to detect the presence of bleeding or oozing esophageal varices, stomach irritation and ulceration, or duodenal ulceration and bleeding. EGD is performed by introducing a flexible fiberoptic endoscope into the mouth, esophagus, and stomach while the patient is under moderate sedation. A camera attached to the scope permits direct visualization of the mucosal lining of the upper GI tract. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) uses the endoscope to inject contrast material via the sphincter of Oddi to view the biliary tract and allow for stone removals, sphincterotomies, biopsies, and stent placements if required. These procedures are described in more detail in Chapter 55.

Physiological Integrity