Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Inflammatory Intestinal Disorders

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

8 Differentiate common types of acute inflammatory bowel disease.

9 Develop a collaborative plan of care for the patient who has appendicitis and peritonitis.

10 Discuss the common causes of gastroenteritis.

12 Identify priority problems for patients with ulcerative colitis.

13 Explain the purpose of and nursing implications related to drug therapy for patients with IBD.

14 Plan priority postoperative care for a patient undergoing surgery for IBD.

15 Develop a hospital discharge teaching plan for patients having surgery for IBD.

16 Explain the role of nutrition therapy in managing the patient with diverticular disease.

17 Describe the comfort measures that the nurse can use for the patient with anal disorders.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Inflammatory bowel health problems affect the small intestine, large intestine (colon), or both. Together, these organs are called the intestinal tract. Continued digestion of food and absorption of nutrients occur primarily in the small intestine (bowel) to meet the body’s needs for energy. Water is reabsorbed in the large intestine to help maintain a fluid balance and promote the passage of waste products. When the intestinal tract and its nearby structures become inflamed, digestion and nutrition may be inadequate to meet a patient’s needs.

Acute Inflammatory Bowel Disorders

Appendicitis, gastroenteritis, and peritonitis are the most common acute inflammatory bowel problems. These disorders are potentially life threatening and can have major systemic complications if not treated promptly.

Appendicitis

Pathophysiology

Appendicitis is an acute inflammation of the vermiform appendix that occurs most often among young adults. It is the most common cause of right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain. The appendix usually extends off the proximal cecum of the colon just below the ileocecal valve. Inflammation occurs when the lumen (opening) of the appendix is obstructed (blocked), leading to infection as bacteria invade the wall of the appendix. The initial obstruction is usually a result of fecaliths (very hard pieces of feces) composed of calcium phosphate–rich mucus and inorganic salts. Less common causes are malignant tumors, helminthes (worms), or other infections.

When the lumen is blocked, the mucosa secretes fluid, increasing the internal pressure and restricting blood flow, resulting in pain. If the process occurs slowly, an abscess may develop, but a rapid process may result in peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum). All complications of peritonitis are serious. Gangrene can occur within 24 to 36 hours, is life threatening, and is one of the most common indications for emergency surgery. Perforation may develop within 24 hours, but the risk rises rapidly after 48 hours. Perforation of the appendix also results in peritonitis with a temperature of greater than 101° F (38.3° C) and a rise in pulse rate.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History taking and tracking the sequence of symptoms are important because nausea or vomiting before abdominal pain can indicate gastroenteritis. Abdominal pain followed by nausea and vomiting can indicate appendicitis. Ask about risk factors such as age, familial tendency, and intra-abdominal tumors. Classically, patients with appendicitis have cramplike pain in the epigastric or periumbilical area. Anorexia is a frequent symptom with nausea and vomiting occurring in many cases.

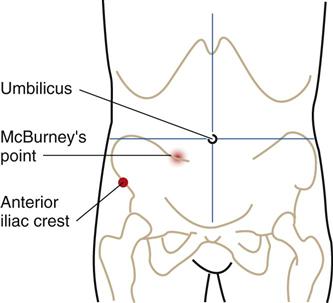

Perform a complete pain assessment. Initially, pain can present anywhere in the abdomen or flank area. As the inflammation and infection progress, the pain becomes more severe and steady and shifts to the RLQ between the anterior iliac crest and the umbilicus. This area is referred to as McBurney’s point (Fig. 60-1). Abdominal pain that increases with cough or movement and is relieved by bending the right hip or the knees suggests perforation and peritonitis. An advanced practice nurse or other health care provider assesses for muscle rigidity and guarding on palpation of the abdomen. The patient may report pain after release of pressure. This is referred to as “rebound” tenderness.

Laboratory findings do not establish the diagnosis, but often there is a moderate elevation of the white blood cell (WBC) count (leukocytosis) to 10,000 to 18,000/mm3 with a “shift to the left” (an increased number of immature WBCs). A WBC elevation to greater than 20,000/mm3 may indicate a perforated appendix. An ultrasound study may show the presence of an enlarged appendix. If symptoms are recurrent or prolonged, a computed tomography (CT) scan can be used for diagnosis and may reveal the presence of a fecalith.

Interventions

All patients with suspected or confirmed appendicitis are hospitalized and examined by a surgeon. When the diagnosis is not clear, the health care team observes the patient before surgical exploration.

Nonsurgical Management

Keep the patient with suspected or known appendicitis on NPO to prepare for the possibility of emergency surgery and to avoid making the inflammation worse.

Surgical Management

Surgery is required as soon as possible. An appendectomy is the removal of the inflamed appendix by one of several surgical approaches. Uncomplicated appendectomy procedures are usually done via laparoscopy. A laparoscopy is a minimally invasive surgical (MIS) procedure with one or more small incisions near the umbilicus through which a small endoscope is placed. Patients having this type of surgery for appendix removal have few postoperative complications. A newer procedure known as natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) (e.g., transvaginal endoscopic appendectomy) does not require an external skin incision. In this procedure, the surgeon places the endoscope into the vagina or other orifice and makes a small incision to enter the peritoneal space. Patients having any type of laparoscopic procedures are typically discharged the same day of surgery with less pain and few complications after discharge. Most patients can return to usual activities in 1 to 2 weeks.

If the diagnosis is not definitive but the patient is at high risk for complications from suspected appendicitis, the surgeon may perform an exploratory laparotomy to rule out appendicitis. A laparotomy is an open surgical approach with a larger abdominal incision for complicated or atypical appendicitis or peritonitis.

Preoperative teaching is often limited because the patient is in pain or may be transferred quickly to the operating suite for emergency surgery. The patient is prepared for general anesthesia and surgery, as described in Chapter 16. After surgery, care of the patient who has undergone an appendectomy is the same as that required for anyone who has received general anesthesia (see Chapter 18).

If peritonitis or abscesses are found, wound drains are inserted and a nasogastric tube may be placed to decompress the stomach and prevent abdominal distention. Administer IV antibiotics and opioid analgesics as prescribed. Help the patient out of bed on the evening of surgery to help prevent respiratory complications, such as atelectasis. He or she may be hospitalized for as long as 3 to 5 days and return to normal activity in 4 to 6 weeks.

Peritonitis

Peritonitis is a life-threatening, acute inflammation of the visceral/parietal peritoneum and endothelial lining of the abdominal cavity. Primary peritonitis is rare and indicates the peritoneum is infected via the bloodstream. This problem is not discussed here.

Pathophysiology

Normally the peritoneal cavity contains about 50 mL of sterile fluid (transudate), which prevents friction in the abdominal cavity during peristalsis. When the peritoneal cavity is contaminated by bacteria, the body first begins an inflammatory reaction walling off a localized area to fight the infection. This local reaction involves vascular dilation and increased capillary permeability, allowing transport of leukocytes and subsequent phagocytosis of the offending organisms. If this walling off process fails, the inflammation spreads and contamination becomes massive, resulting in diffuse (widespread) peritonitis.

Peritonitis is most often caused by contamination of the peritoneal cavity by bacteria or chemicals. Bacteria gain entry into the peritoneum by perforation (from appendicitis, diverticulitis, peptic ulcer disease) or from an external penetrating wound, a gangrenous gallbladder, bowel obstruction, or ascending infection through the genital tract. Less common causes include perforating tumors, leakage or contamination during surgery, and infection by skin pathogens in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Common bacteria responsible for peritonitis include Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Pneumococcus, and Gonococcus. Chemical peritonitis results from leakage of bile, pancreatic enzymes, and gastric acid.

When diagnosis and treatment of peritonitis are delayed, blood vessel dilation continues. The body responds to the continuing infectious process by shunting extra blood to the area of inflammation (hyperemia). Fluid is shifted from the extracellular fluid compartment into the peritoneal cavity, connective tissues, and GI tract (“third spacing”). This shift of fluid can result in a significant decrease in circulatory volume and hypovolemic shock. Severely decreased circulatory volume can result in insufficient perfusion of the kidneys, leading to kidney failure with electrolyte imbalance. Assess for clinical manifestations of these life-threatening problems.

Peristalsis slows or stops in response to severe peritoneal inflammation, and the lumen of the bowel becomes distended with gas and fluid. Fluid that normally flows to the small bowel and the colon for reabsorption accumulates in the intestine in volumes of 7 to 8 L daily. The toxins or bacteria responsible for the peritonitis can also enter the bloodstream from the peritoneal area and lead to bacteremia or septicemia (bacterial invasion of the blood).

Respiratory problems can occur as a result of increased abdominal pressure against the diaphragm from intestinal distention and fluid shifts to the peritoneal cavity. Pain can interfere with respirations at a time when the patient has an increased oxygen demand because of the infectious process.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Ask the patient about abdominal pain, and determine the character of the pain (e.g., cramping, sharp, aching), location of the pain, and whether the pain is localized or generalized. Ask about a history of a low-grade fever or recent spikes in temperature.

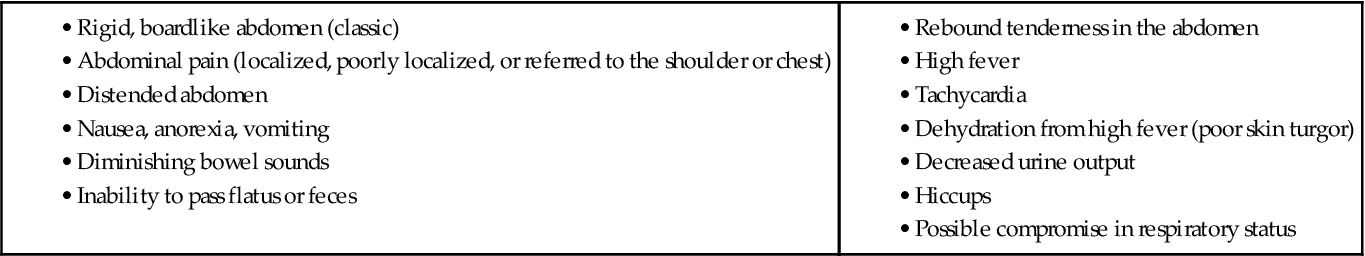

Physical findings of peritonitis (Chart 60-1) depend on several factors: the stage of the disease, the ability of the body to localize the process by walling off the infection, and whether the inflammation has progressed to generalized peritonitis. The patient most often appears acutely ill, lying still, possibly with the knees flexed. Movement is guarded, and he or she may report and show signs of pain (e.g., facial grimacing) with coughing or movement of any type. During inspection, observe for progressive abdominal distention, often seen when the inflammation markedly reduces intestinal motility. Auscultate for bowel sounds, which usually disappear with progression of the inflammation.

The cardinal signs of peritonitis are abdominal pain and tenderness. In the patient with localized peritonitis, the abdomen is tender on palpation in a well-defined area with rebound tenderness in this area. With generalized peritonitis, tenderness is widespread.

White blood cell (WBC) counts are often elevated to 20,000/mm3 with a high neutrophil count. Blood culture studies may be done to determine whether septicemia has occurred and to identify the causative organism to enable appropriate therapy. The health care provider requests laboratory tests to assess fluid and electrolyte balance and renal status, including electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. Oxygen saturation and end–carbon dioxide monitoring may be obtained to assess respiratory function and acid-base balance.

Abdominal x-rays can assess for free air or fluid in the abdominal cavity, indicating perforation. The x-rays may also show dilation, edema, and inflammation of the small and large intestines. An abdominal sonogram may be useful in locating the problem.

Interventions

Patients with peritonitis are hospitalized because of the severe nature of the illness. If complications are extensive, the patients are often admitted to a critical care unit. Nursing interventions focus on the early identification of complications.

Nonsurgical Management

The physician prescribes IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics immediately after establishing the diagnosis of peritonitis. IV fluids are used to replace fluids collected in the peritoneum and bowel. Monitor daily weight and intake and output carefully. A nasogastric tube (NGT) decompresses the stomach and the intestine, and the patient is NPO. Apply oxygen as prescribed and according to the patient’s respiratory status and oxygen saturation via pulse oximetry. Administer analgesics, and monitor for pain control. Document pain assessments thoroughly. A surgical consultation is requested in case surgery should become necessary.

Surgical Management

Abdominal surgery is the usual treatment for identifying and repairing the cause of the peritonitis. If the patient is so critically ill that surgery would be life threatening, it may be delayed. Surgery focuses on controlling the contamination, removing foreign material from the peritoneal cavity, and draining collected fluid.

Exploratory laparotomy (surgical opening into the abdomen) or laparoscopy is used to remove or repair the inflamed or perforated organ (e.g., appendectomy for an inflamed appendix; a colon resection, with or without a colostomy, for a perforated diverticulum). Before the incision(s) is closed, the surgeon irrigates the peritoneum with antibiotic solutions. Several catheters may be inserted to drain the cavity and provide a route for irrigation after surgery.

The preoperative care is similar to that described in Chapter 16 for patients having general anesthesia. Chapter 18 describes general postoperative care for exploratory laparotomy. Multi-system complications can occur with peritonitis. Loss of fluids from the extracellular space to the peritoneal cavity, NGT suctioning, and NPO status require that the patient receives IV fluid replacement. Be sure that unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) carefully measure intake and output. Fluid rates may be changed frequently based on laboratory values and patient condition.

The patient has one or more incisions and drains. If an open surgical procedure is needed, the infection may slow healing of an incision or the incision may be partially open to heal by second or third intention. These wounds require special care involving manual irrigation or packing as prescribed by the surgeon. If the surgeon requests peritoneal irrigation through a drain, maintain sterile technique during manual irrigation. Assess whether the patient retains the fluid used for irrigation by comparing the amount of fluid returned with the amount of fluid instilled. Fluid retention could cause abdominal distention or pain.

Community-Based Care

The length of hospitalization depends on the extent and severity of the infectious process. Patients who have a localized abscess drained and who respond to antibiotics and IV fluids without multi-system complications are discharged in several days. Others may require mechanical ventilation or hemodialysis with longer hospital stays. Some patients may be transferred to a transitional care unit to complete their antibiotic therapy and recovery. Convalescence is often longer than for other surgeries because of multi-system involvement.

When discharged home, assess the patient’s ability for self-management at home with the added task of incision care and a reduced activity tolerance. Provide the patient and family with written and oral instructions to report these problems to the health care provider immediately:

• Unusual or foul-smelling drainage

• Swelling, redness, or warmth or bleeding from the incision site

• A temperature higher than 101° F (38° C)

Patients with an incision healing by second or third intention may require dressings, solution, and catheter-tipped syringes to irrigate the wound. A home care nurse may be needed to assess, irrigate, or pack the wound and change the dressing as needed until the patient and family feel comfortable with the procedure. If the patient needs assistance with ADLs, a home care aide or temporary placement in a skilled care facility may be indicated. Collaborate with the case manager (CM) to determine the most appropriate setting for seamless continuing care in the community.

Review information about antibiotics and analgesics. For patients taking oral opioid analgesics such as oxycodone with acetaminophen (Tylox, Percocet, Endocet ![]() ) for any length of time, a stool softener such as docusate sodium (Colace, Regulex

) for any length of time, a stool softener such as docusate sodium (Colace, Regulex ![]() ) may be prescribed. Older adults are especially at risk for constipation from codeine-based drugs.

) may be prescribed. Older adults are especially at risk for constipation from codeine-based drugs.

Teach patients to refrain from any lifting for at least 6 weeks. Other activity limitations are made on an individual basis with the physician’s recommendation.

Gastroenteritis

Pathophysiology

Gastroenteritis is an increase in the frequency and water content of stools and/or vomiting as a result of inflammation of the mucous membranes of the stomach and intestinal tract. It affects mainly the small bowel and can be caused by either viral or bacterial infections, which have similar manifestations. They are considered self-limiting in their course unless complications occur. All organisms implicated in gastroenteritis can cause diarrhea. However, the organisms discussed in this section have distinguishing characteristics.

Some clinicians include shigellosis when discussing gastroenteritis. Others consider shigellosis separately as a dysentery type of illness. Dysenteries affect the large bowel. Gastroenteritis affects the small bowel. Other clinicians classify infectious disease of the intestine as bacterial, viral, or parasitic, without using the term gastroenteritis.

Food poisoning is sometimes described in conjunction with gastroenteritis with specific reference to the organism causing the food poisoning. Gastroenteritis, however, differs from food poisoning with regard to transmission in the body, incubation time, and effect on immunity.

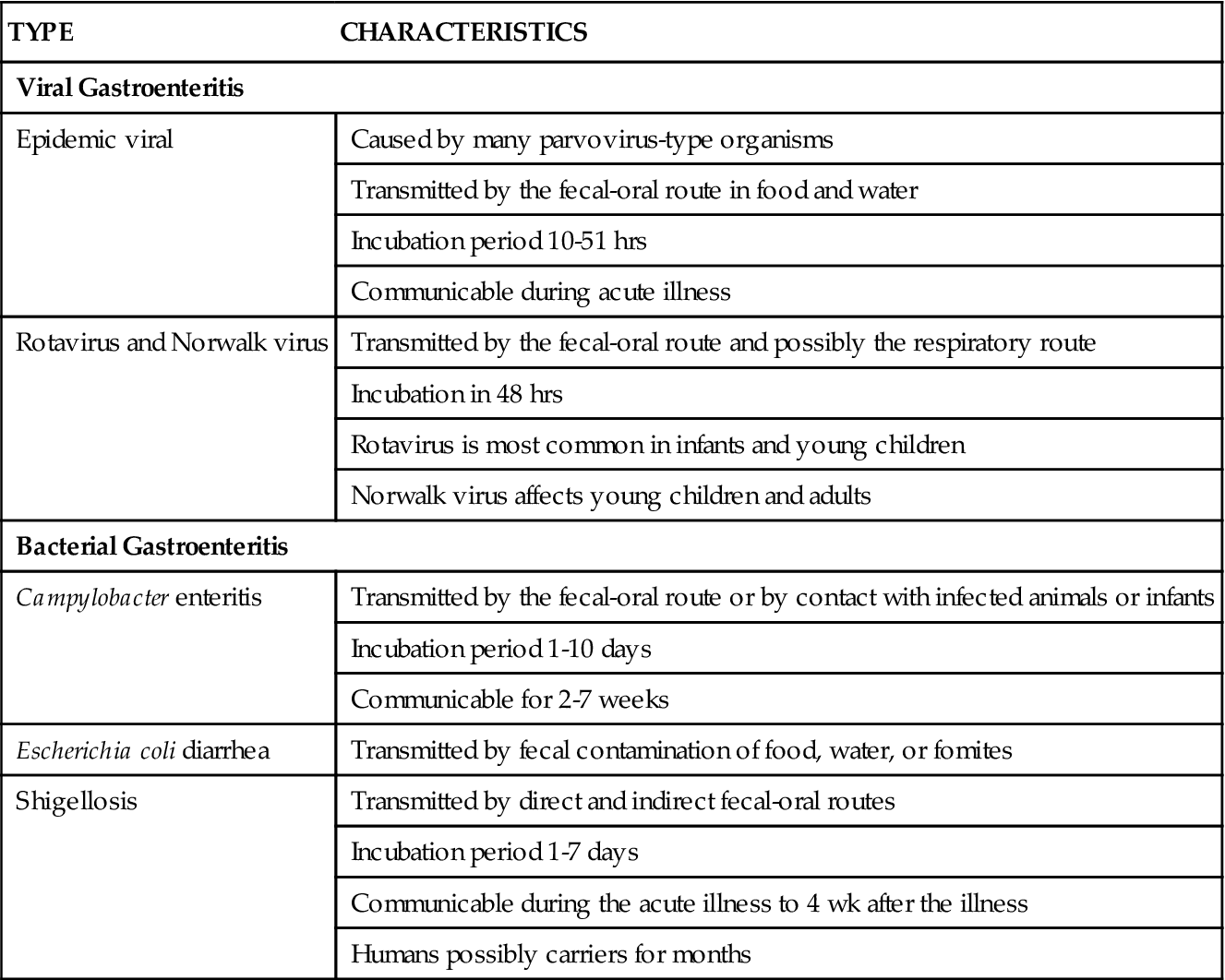

The following discussion of gastroenteritis includes the epidemic viral form and the bacterial forms (Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and shigellosis) (Table 60-1). Organisms associated with food poisoning are discussed later in this chapter.

TABLE 60-1

COMMON TYPES OF GASTROENTERITIS AND THEIR CHARACTERISTICS

| TYPE | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Viral Gastroenteritis | |

| Epidemic viral | Caused by many parvovirus-type organisms |

| Transmitted by the fecal-oral route in food and water | |

| Incubation period 10-51 hrs | |

| Communicable during acute illness | |

| Rotavirus and Norwalk virus | Transmitted by the fecal-oral route and possibly the respiratory route |

| Incubation in 48 hrs | |

| Rotavirus is most common in infants and young children | |

| Norwalk virus affects young children and adults | |

| Bacterial Gastroenteritis | |

| Campylobacter enteritis | Transmitted by the fecal-oral route or by contact with infected animals or infants |

| Incubation period 1-10 days | |

| Communicable for 2-7 weeks | |

| Escherichia coli diarrhea | Transmitted by fecal contamination of food, water, or fomites |

| Shigellosis | Transmitted by direct and indirect fecal-oral routes |

| Incubation period 1-7 days | |

| Communicable during the acute illness to 4 wk after the illness | |

| Humans possibly carriers for months | |

Infection with viral and bacterial organisms can produce GI illnesses that cause watery diarrhea. These disorders may be caused by noninflammatory, inflammatory, or penetrating mechanisms. Organisms such as enterotoxigenic E. coli can release enterotoxin (a noninflammatory toxic substance specific to the intestinal mucosa), which results in diarrhea. Shigella or Campylobacter can attach itself to mucosal epithelium without penetrating it, resulting in destruction of the intestinal villi and malabsorption. Infections that are caused by bacterial toxins reduce the absorptive capacity of the distal small bowel and proximal colon, resulting in diarrhea. Finally, the organism can penetrate the intestine, causing cellular destruction, necrosis, and a potential for ulceration. Diarrhea occurs often with white blood cells (WBCs) or red blood cells (RBCs) present in the stool.

All of these organisms are transmitted via the oral-fecal route and result in increased GI motility, with fluids and electrolytes being secreted into the intestine at rapid rates. Invading organisms more easily attach to the intestinal mucosa if the normal intestinal flora is altered. This can occur in patients who are receiving antibiotics, are malnourished, or are debilitated. Two groups of viruses, the rotaviruses (which usually affect young children) and Norwalk virus, as well as bacterial pathogens, are the most common causes of gastroenteritis. Rotaviruses can also affect older adults in group settings, such as long-term care facilities.

The three most common types of bacterial gastroenteritis are E. coli diarrhea (“traveler’s diarrhea”), Campylobacter enteritis (another “traveler’s diarrhea”), and Shigellosis (bacillary dysentery). The reservoirs of E. coli are humans, who are often asymptomatic.

Diarrhea caused by E. coli and Campylobacter occurs worldwide, commonly in epidemic outbreaks. E. coli epidemics are highest in areas of poor sanitation during warm months. Campylobacter incidence is highest during warm months. Shigellosis occurs in every age-group but most frequently in children (younger than 10 years) and older adults because of their depressed immune systems. Outbreaks of shigellosis are common in areas with crowded living conditions, such as in correctional facilities.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The patient history can provide information related to the potential cause of the illness. Ask about recent travel, especially to tropical regions of Asia, Africa, or Central or South America. Some areas of Mexico may also be the source of gastroenteritis. Newcomers (immigrants) from these countries often have gastroenteritis. Traveler’s diarrhea can begin 3 days to 2 weeks after the patient’s arrival.

The patient who has gastroenteritis usually looks ill. Nausea and vomiting can occur with all types of gastroenteritis but are usually limited to the first 1 or 2 days. Patients have diarrhea, which varies in consistency and amount with the causative organism.

In patients with epidemic viral gastroenteritis, myalgia (muscle aches), headache, and malaise are often reported. Weakness and cardiac dysrhythmias may be the result of loss of potassium (hypokalemia) from diarrhea. Monitor for and document manifestations of hypokalemia.

Diarrhea associated with epidemic viral gastroenteritis is commonly limited to 24 to 48 hours. Infection with the Norwalk virus has a rapid onset of nausea, abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea. This enteritis is usually mild. Campylobacter enteritis is a more severe disease with foul-smelling stools containing blood, which can number 20 to 30 per day for up to 7 days. E. coli gastroenteritis may or may not have blood or mucus in the stool. Diarrhea can last for up to 10 days. Shigella causes stools to have blood and mucus, which can continue for up to 5 days. Monitor for and document the number of stools daily for the patient who is hospitalized.

As part of the laboratory assessment, Gram stain of stool is usually done before culture. Cultures positive for the organism are diagnostic (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). Many WBCs on Gram stain suggest shigellosis. The presence of WBCs and RBCs in the stool may indicate Campylobacter gastroenteritis.

Interventions

For any type of gastroenteritis, encourage fluid replacement. The amount and route of fluid administration are determined by the patient’s hydration status and overall health condition.

Fluid Replacement

Teach patients to drink extra fluids to replace fluid lost through vomiting and diarrhea. Depending on the patient’s age and severity of dehydration, he or she may be admitted to the hospital for gastroenteritis or may stay in the emergency department or urgent care center until adequate hydration is restored.

Obtain a weight, orthostatic blood pressure, and other vital sign measurements at admission. IV fluids such as half-strength normal saline (0.45% sodium chloride) to replace sodium lost in vomitus, with or without potassium supplements, are infused as prescribed. Potassium is usually needed for patients with excessive diarrhea. Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, and weight. A rapid gain or loss of 1 kg (2.2 lbs) of body weight is equivalent to the gain or loss of 1 L of fluid. Advise the patient to alternate periods of rest and activity.

Depending on the type of gastroenteritis, especially if the geographic area is experiencing epidemic infections, the local health department may need to be notified. For example, it is mandatory that every case of shigellosis be reported. In some endemic areas, Campylobacter enteritis must be reported.

Drug Therapy

Drugs that suppress intestinal motility may not be given for bacterial or viral gastroenteritis. Use of these drugs can prevent the infecting organisms from being eliminated from the body. If the health care provider determines that antiperistaltic agents are necessary, an initial dose of loperamide (Imodium) 4 mg can be administered orally, followed by 2 mg after each loose stool, up to 16 mg daily.

Treatment with antibiotics may be needed if the gastroenteritis is due to bacterial infection with fever and severe diarrhea. Depending on the type and severity of the illness, examples of drugs that may be prescribed include ciprofloxacin (Cipro), levofloxacin (Levaquin), or azithromycin (Zithromax). If the gastroenteritis is due to shigellosis, anti-infective agents such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Septra DS, Bactrim DS, Roubac ![]() ) or ciprofloxacin are prescribed.

) or ciprofloxacin are prescribed.

For relatively short-term diarrhea of 24 to 48 hours’ duration, the diagnosis is based primarily on the patient’s history and clinical manifestations, not by a stool examination. When diarrhea is severe or persists for long periods, the stool is examined to determine the causative organism and to begin specific treatment. It should be determined whether the diarrhea is caused by Salmonella or by parasites because these organisms respond to specific medications (see p. 1289 in the Parasitic Infection section). Diarrhea that continues longer than 10 days, especially if associated with nocturnal diarrhea, is probably not due to gastroenteritis.

Skin Care

Frequent stools that are rich in electrolytes and enzymes, as well as frequent wiping and washing of the anal region, can irritate the skin. Teach the patient to avoid toilet paper and harsh soaps. Ideally, he or she can gently clean the area with warm water or an absorbent material, followed by thorough but gentle drying. Cream, oil, or gel can be applied to a damp, warm washcloth to remove stool that sticks to open skin. Special prepared skin wipes can also be used. Protective barrier cream can be applied to the skin between stools. Sitz baths for 10 minutes two or three times daily can also relieve discomfort.

If leakage of stool is a problem, the patient can use absorbent cotton or panty liner and keep it in place with snug underwear. For patients who are incontinent, remind unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) to keep the perineal and buttock areas clean and dry. The use of incontinent pads at night instead of briefs allows air to circulate to the skin and prevents irritation.

Teaching for Self-Management

During the acute phase of the illness, teach the patient and family about the importance of fluid replacement. Teaching the patient and family about reducing the risk for transmission of gastroenteritis is also important (Chart 60-2). Adhere to these precautions for up to 7 weeks after the illness or up to several months if Shigella was the offending organism.

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are the two most common inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) that affect adults. Comparisons and differences are listed in Table 60-2. Viral and bacterial dysenteries can cause symptoms similar to those of IBD, and other problems must be ruled out before a definitive diagnosis is made.

TABLE 60-2

DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND CROHN’S DISEASE

| FEATURE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS | CROHN’S DISEASE |

| Location | Begins in the rectum and proceeds in a continuous manner toward the cecum | Most often in the terminal ileum, with patchy involvement through all layers of the bowel |

| Etiology | Unknown | Unknown |

| Peak incidence at age | 15-25 yr and 55-65 yr | 15-40 yr |

| Number of stools | 10-20 liquid, bloody stools per day | 5-6 soft, loose stools per day, non-bloody |

| Complications | Hemorrhage Nutritional deficiencies | Fistulas (common) Nutritional deficiencies |

| Need for surgery | Infrequent | Frequent |

The approach to each patient is individualized. Encourage patients to self-manage their disease by learning about the illness, treatment, drugs, and complications.

Ulcerative Colitis

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative colitis (UC) creates widespread inflammation of mainly the rectum and rectosigmoid colon but can extend to the entire colon when the disease is extensive. Distribution of the disease can remain constant for years. UC is a disease that is associated with periodic remissions and exacerbations (flare-ups) (McCance et al., 2010). Many factors can cause exacerbations, including intestinal infections.

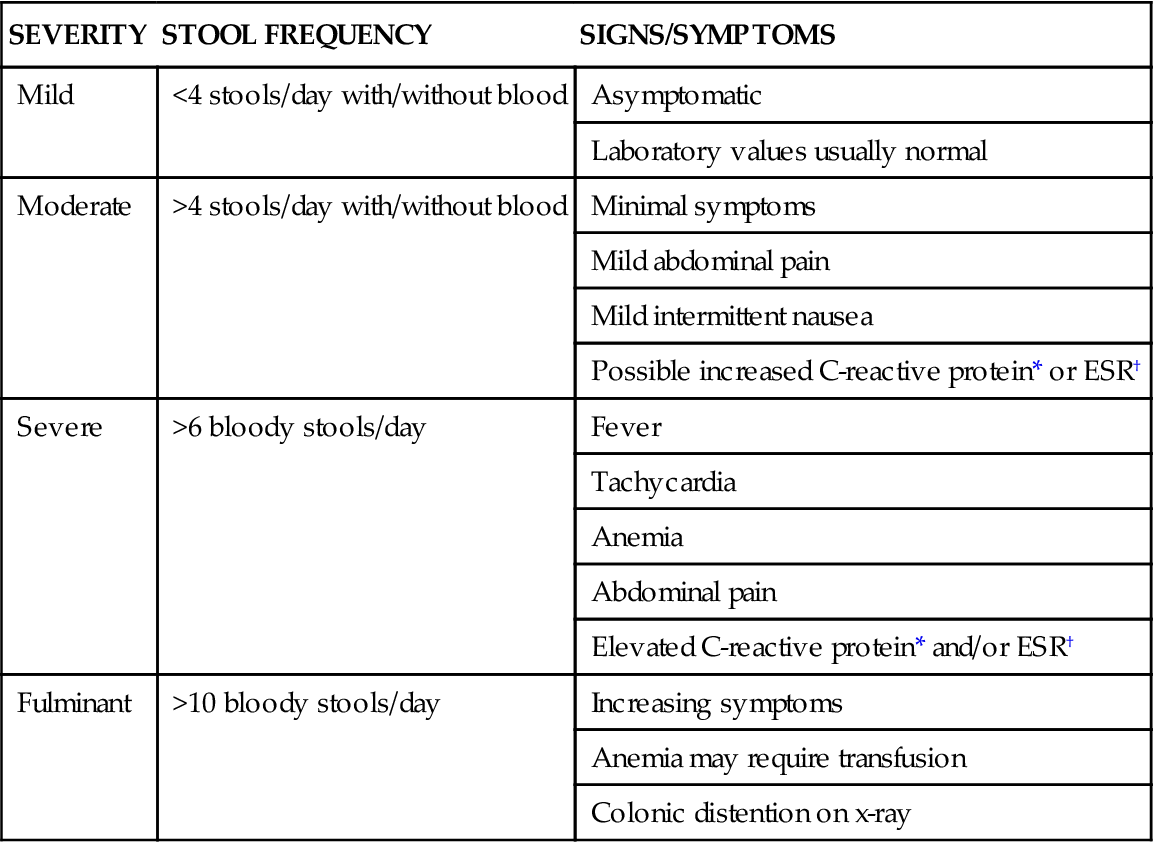

The intestinal mucosa becomes hyperemic (has increased blood flow), edematous, and reddened. In more severe inflammation, the lining can bleed and small erosions, or ulcers, occur. Abscesses can form in these ulcerative areas and result in tissue necrosis (cell death). Continued edema and mucosal thickening can lead to a narrowed colon and possibly a partial bowel obstruction. Table 60-3 lists the categories of the severity of UC.

TABLE 60-3

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGISTS CLASSIFICATION OF UC SEVERITY

| SEVERITY | STOOL FREQUENCY | SIGNS/SYMPTOMS |

| Mild | <4 stools/day with/without blood | Asymptomatic |

| Laboratory values usually normal | ||

| Moderate | >4 stools/day with/without blood | Minimal symptoms |

| Mild abdominal pain | ||

| Mild intermittent nausea | ||

| Possible increased C-reactive protein* or ESR† | ||

| Severe | >6 bloody stools/day | Fever |

| Tachycardia | ||

| Anemia | ||

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Elevated C-reactive protein* and/or ESR† | ||

| Fulminant | >10 bloody stools/day | Increasing symptoms |

| Anemia may require transfusion | ||

| Colonic distention on x-ray |

*C-reactive protein is a sensitive acute-phase serum marker that is evident in the first 6 hours of an inflammatory process.

†ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) may be helpful but is less sensitive than C-reactive protein.

Adapted from Present, D.H. (2006). Current and investigational approaches in the management of ulcerative colitis. Secaucus, NJ: Thomson Professional Postgraduate Services/Shire Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The patient’s stool typically contains blood and mucus. Patients report tenesmus (an unpleasant and urgent sensation to defecate) and lower abdominal colicky pain relieved with defecation. Malaise, anorexia, anemia, dehydration, fever, and weight loss are common. Extraintestinal manifestations such as migratory polyarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and erythema nodosum are present in a large number of patients. The common complications of UC, including extraintestinal manifestations, are listed in Table 60-4.

TABLE 60-4

COMPLICATIONS OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND CROHN’S DISEASE

| COMPLICATION | DESCRIPTION |

| Hemorrhage/perforation | Lower gastrointestinal bleeding results from erosion of the bowel wall. |

| Abscess formation | Localized pockets of infection develop in the ulcerated bowel lining. |

| Toxic megacolon | Paralysis of the colon causes dilation and subsequent colonic ileus, possibly perforation. |

| Malabsorption | Essential nutrients cannot be absorbed through the diseased intestinal wall, causing anemia and malnutrition (most common in Crohn’s disease). |

| Nonmechanical bowel obstruction | Obstruction results from toxic megacolon or cancer. |

| Fistulas | In Crohn’s disease in which the inflammation is transmural, fistulas can occur anywhere but usually track between the bowel and bladder resulting in pyuria and fecaluria. |

| Colorectal cancer | Patients with ulcerative colitis with a history longer than 10 years have a high risk for colorectal cancer. This complication accounts for about one third of all deaths related to ulcerative colitis. |

| Extraintestinal complications | Complications include arthritis, hepatic and biliary disease (especially cholelithiasis), oral and skin lesions, and ocular disorders, such as iritis. The cause is unknown. |

| Osteoporosis | Osteoporosis occurs especially in patients with Crohn’s disease. |

Etiology and Genetic Risk

The exact cause of UC is unknown, but genetic and immunologic factors have been suspected. A genetic basis of the disease has been supported because it is often found in families and twins. Immunologic causes, including autoimmune dysfunction, are likely the etiology of extraintestinal manifestations of the disease. Epithelial antibodies in the IgG class have been identified in the blood of some patients with UC (McCance et al., 2010).

With long-term disease, cellular changes can occur that increase the risk for colon cancer. Damage from proinflammatory cytokines, such as specific interleukins (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, have cytotoxic effects on the colonic mucosa (McCance et al., 2010).

Incidence/Prevalence

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects about 1.4 million people in the United States and is split about equally between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (discussed later). Peak age for being diagnosed with UC is between 30 and 40 years and again at 55 to 65 years. Women are more often affected than men in their younger years, but men have the disease more often as middle-aged and older adults (Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, 2008).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Collect data on family history of IBD, previous and current therapy for the illness, and dates and types of surgery. Obtain a nutrition history, including intolerance of milk and milk products and fried, spicy, or hot foods. Ask about usual bowel elimination pattern (color, number, consistency, and character of stools), abdominal pain, tenesmus, anorexia, and fatigue. Note any relationship between diarrhea, timing of meals, emotional distress, and activity. Inquire about recent (past 2 to 3 month) exposure to antibiotics suggesting Clostridium difficile infection. Has the patient traveled to or emigrated from tropical areas? Ask about recent use of NSAIDs that can either present with the initial diagnosis or cause a flare-up of the disease. Ask about any extraintestinal symptoms such as arthritis, mouth sores, vision problems, and skin disorders.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms vary with an acuteness of onset. Vital signs are usually within normal limits in mild disease. In more severe cases, the patient may have a low-grade fever (99° to 100° F [37.2° to 37.8° C]). The physical assessment findings are usually nonspecific, and in milder cases the physical examination may be normal. Viral and bacterial infections cause symptoms similar to those of UC.

Note any abdominal distention along the colon. Patients with fever associated with tachycardia may indicate peritonitis, dehydration, and bowel perforation. Assess for clinical manifestations associated with extraintestinal complications, such as inflamed joints and lesions inside the mouth.

Psychosocial Assessment

Many patients are very concerned about the frequency of stools and the presence of blood. The inability to control the disease symptoms, particularly diarrhea, can be disruptive and stress producing. Severe illness may limit the patient’s activities outside the home with fear of fecal incontinence resulting in feeling “tied to the toilet.” Severe anxiety and depression may result. Eating may be associated with pain and cramping and an increased frequency of stools. Mealtimes may become unpleasant experiences. Frequent visits to health care providers and close monitoring of the colon mucosa for abnormal cell changes can be anxiety provoking.

Assess the patient’s understanding of the illness and its impact on his or her lifestyle. Encourage and support the patient while exploring:

Laboratory Assessment

As a result of chronic blood loss, hematocrit and hemoglobin levels may be low, which indicates anemia and a chronic disease state. An increased WBC count, C-reactive protein, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is consistent with inflammatory disease. Blood levels of sodium, potassium, and chloride may be low as a result of frequent diarrheal stools and malabsorption through the diseased bowel (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). Hypoalbuminemia (decreased serum albumin) is found in patients with extensive disease from losing protein in the stool.

Other Diagnostic Assessment

A colonoscopy is the most definitive test for diagnosing UC. Annual colonoscopies are recommended when the patient has longer than a 10-year history of UC involving the entire colon. In some cases, a computed tomography (CT) scan may be done to confirm the disease or its complications. Barium enemas with air contrast can show differences between UC and Crohn’s disease and identify complications, mucosal patterns, and the distribution and depth of disease involvement. In early disease, the barium enema may show incomplete filling as a result of inflammation and fine ulcerations along the bowel contour, which appear deeper in more advanced disease.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with ulcerative colitis are:

Planning and Implementation

Decreasing Diarrhea and Bowel Incontinence

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The major concern for a patient with ulcerative colitis is the occurrence of frequent, bloody diarrhea and fecal incontinence from tenesmus. Therefore, with treatment, the patient is expected to have decreased diarrhea, formed stools, and control of bowel movements.

Interventions.

Many measures are used to relieve symptoms and to reduce intestinal motility, decrease inflammation, and promote intestinal healing. Nonsurgical and/or surgical management may be needed.

Nonsurgical Management.

Nonsurgical management includes drug and nutrition therapy. The use of physical and emotional rest is also an important consideration. Teach the patient to record color, volume, frequency, and consistency of stools to determine severity of the problem.

Monitor the skin in the perianal area for irritation and ulceration resulting from loose, frequent stools. Stool cultures may be sent for analysis if diarrhea continues. Have the patient weigh himself or herself one or two times per week. If the patient is hospitalized, remind unlicensed assistive personnel to weigh him or her on admission and daily and document all weights.