M. Linda Workman

Care of Patients with Infectious Respiratory Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

10 Perform focused respiratory assessment and re-assessment.

11 Recognize manifestations of infectious respiratory diseases.

14 Administer oxygen therapy to the patient with hypoxemia, and evaluate the response.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Tuberculosis

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenge and Decision-Making Challenge Questions

Audio Clip: High- and Low-Pitched Crackles

Audio Clip: High- and Low-Pitched Wheezes

Audio Clip: Stridor

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Concept Map: Community-Acquired (CA) Bacterial Pneumonia

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Disorders of the Nose and Sinuses

Rhinitis

Pathophysiology

Rhinitis, an inflammation of the nasal mucosa, is a common problem of the nose and often also involves the sinuses. It can be caused by infection (viral or bacterial) or contact with allergens. Often an allergic rhinitis will make the mucous membranes more susceptible to invasion, and then infection accompanies the allergy. Regardless of the cause, rhinitis is uncomfortable.

Allergic rhinitis, often called hay fever or allergies, is triggered by hypersensitivity reactions to airborne allergens, especially plant pollens or molds. Some episodes are “seasonal” because they recur at the same time each year and last a few weeks. Perennial rhinitis occurs either intermittently with no seasonal pattern or continuously whenever the person is exposed to an offending allergen such as dust, animal dander, wool, or foods (e.g., seafood). Rhinitis also occurs as a “rebound” nasal congestion from overuse of nose drops or sprays (rhinitis medicamentosa) and chronic nasal inhalation of cocaine.

Acute viral rhinitis (coryza, or the common cold) is caused by any of over 200 viruses. It spreads from person to person by droplets from sneezing or coughing and by direct contact. Colds are most contagious in the first 2 to 3 days after symptoms appear. Colds are self-limiting unless a bacterial infection occurs at the same time. Complications occur most often in immunosuppressed people and older adults, especially if they live or work in crowded conditions or in group settings.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

In both acute and chronic allergic rhinitis, the presence of the allergen causes a release of histamine and other mediators from white blood cells (WBCs) in the nasal mucosa. These mediators bind to blood vessel receptors, causing local blood vessel dilation and capillary leak, leading to local edema and swelling. Manifestations include headache, nasal irritation, sneezing, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea (watery drainage from the nose), and itchy, watery eyes.

Viral or bacterial invasion of the nasal passages causes the same local tissue responses as allergic rhinitis. Often the patient also has systemic manifestations, including a sore, dry throat and a low-grade fever.

Management of the patient with any type of rhinitis focuses on symptom relief and patient education. Teach him or her about correct use of the drug therapy prescribed.

Drug therapy, including antihistamines and decongestants, is prescribed but must be used with caution in the older adult because of side effects such as vertigo, hypertension, and urinary retention. Antihistamines, leukotriene inhibitors, and mast cell stabilizers block the chemicals released by WBCs from binding to receptors in nasal tissues or reduce the amount of mediator present, preventing local edema and itching. Decongestants constrict blood vessels and decrease edema. Antipyretics are given if fever is present. Antibiotics are prescribed only when a bacterial infection accompanies rhinitis. Rhinitis caused by overuse of nose drops or sprays is treated by discontinuing the drug. Steroid nasal sprays may be used to decrease the rebound nasal congestion during the first week after discontinuing the drug (Regan, 2009).

Complementary and alternative therapies may be used to decrease the severity of acute viral rhinitis for some people early in the course of the problem. Common agents used for this purpose are echinacea, large doses of vitamin C, and zinc preparations such as COLD-EEZE or Zicam. These products may help increase nonspecific immune function.

Supportive therapy can increase the patient’s comfort and help prevent spread of the infection. Instruct the patient about the importance of rest (8 to 10 hours a day) and fluid intake of at least 2000 mL/day unless other health problems require fluid restriction. Humidifying the air helps relieve congestion. Humidity can be increased with a room humidifier or by breathing steamy air in the bathroom after running hot shower water.

Teach patients to reduce the risk for spreading colds by thoroughly washing hands, especially after nose blowing, sneezing, coughing, rubbing the eyes, or touching the face. Other precautions include staying home from work, school, or places where people gather; covering the mouth and nose with a tissue when sneezing or coughing; disposing properly of used tissues immediately; and avoiding close contact with other people (e.g., kissing, hugging, handshaking). Stress the need to avoid close contact with people who are more susceptible to infection, such as older adults, infants, and anyone who has a chronic respiratory problem. An uncomplicated cold typically subsides within 7 to 10 days.

Sinusitis

Pathophysiology

Sinusitis is an inflammation of the mucous membranes of one or more of the sinuses. Swelling can obstruct the flow of secretions from the sinuses, which may then become infected. The disorder often follows rhinitis. Other conditions leading to sinusitis include deviated nasal septum, nasal polyps or tumors, inhaled air pollutants or cocaine, facial trauma, nasal intubation, dental infection, or decreased immune function.

The most common organisms causing sinus infection are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Diplococcus, and Bacteroides. Sinusitis most often develops in the maxillary and frontal sinuses. Complications include cellulitis, abscess, and meningitis.

Diagnosis is made on the basis of the patient’s history and manifestations. Transillumination (reflection of light through tissues) of the affected sinus is decreased. This can be assessed by having the patient place a lighted penlight tip into the mouth and closing the lips around it in a darkened room. Non-swollen sinuses reflect light through the skin as seen as a red glow on the cheek between the eye and the lip. Sinuses that are swollen or filled with secretions have a reduced or absent glow. Other tests for sinusitis include sinus x-rays, endoscopic examination, and computed tomography (CT). Bacterial sinusitis is usually indicated by purulent drainage from one or both nares and lack of response to decongestant therapy.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assess for manifestations of sinusitis, including nasal swelling and congestion, headache, facial pressure, and pain (usually worse when the head is tilted forward or is in a dependent position). Other manifestations include tenderness to touch over the involved area, low-grade fever, cough, and purulent or bloody nasal drainage.

Nonsurgical Management

Treatment includes the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin [Amoxil]), analgesics for pain and fever (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol, Abenol ![]() , Atasol

, Atasol ![]() , Panadol]), decongestants (e.g., phenylephrine [Neo-Synephrine]), steam humidification, hot and wet packs over the sinus area, and nasal saline irrigations. Teach the patient to increase fluid intake unless another medical problem requires fluid restriction. If this treatment plan is not successful, he or she may need to be evaluated with sinus x-rays and CT scans. Surgical intervention may be needed if nonsurgical management fails to provide relief.

, Panadol]), decongestants (e.g., phenylephrine [Neo-Synephrine]), steam humidification, hot and wet packs over the sinus area, and nasal saline irrigations. Teach the patient to increase fluid intake unless another medical problem requires fluid restriction. If this treatment plan is not successful, he or she may need to be evaluated with sinus x-rays and CT scans. Surgical intervention may be needed if nonsurgical management fails to provide relief.

Surgical Management

A common procedure used for sinusitis that does not respond to drug therapy is functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS). Small endoscopes (sinoscopes) are used to first visualize the area. Instruments attached to the sinoscopes are used to open the nasal ostium and remove infected mucosa or improve the pathway for nasal drainage. A balloon catheter may also be used during FESS to change the shape of the nasal ostium to relieve obstruction and promote drainage (Regan, 2009). The procedures take only minutes, although mucosal healing may take from 4 to 6 weeks. Pain, swelling, and bleeding are much less than for more traditional sinus surgery procedures. Instruct the patient to use saline nasal sprays frequently (every 2 to 4 hours) to prevent mucosal crusting and promote healing. After more traditional nasal surgery or endoscopic surgery, the patient may have difficulty eating for a few days because of pain and swelling. Chart 33-1 describes the best practices for care after these surgeries.

Disorders of the Oral Pharynx and Tonsils

Pharyngitis

Pathophysiology

Pharyngitis, or “sore throat,” is a common inflammation of the pharyngeal mucous membranes that often occurs with rhinitis and sinusitis. It accounts for 1.2% of all office visits each year in the United States (Schappert & Rechsteiner, 2008).

Acute pharyngitis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, other organisms, trauma, dehydration, irritants, and tobacco or alcohol use. A common bacterium causing pharyngitis is group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, but most adult cases are caused by a virus (Hoyle, 2009).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

The patient with pharyngitis has throat soreness and dryness, throat pain, pain on swallowing (odynophagia), difficulty swallowing, and fever. Viral and bacterial pharyngitis are often difficult to distinguish on physical assessment. When inspecting a throat infected with either virus or bacteria, mild to severe redness may be seen with or without enlarged tonsils and with or without exudate. Ask about nasal discharge, which varies from thin and watery to thick and purulent. Enlargement of neck lymph nodes occurs with both viral and bacterial pharyngitis.

Bacterial infections are often associated with enlarged red tonsils, exudate, purulent nasal discharge, and local lymph node enlargement. Chart 33-2 compares the manifestations of viral and bacterial pharyngitis. Viral pharyngitis is contagious for 2 to 3 days. Symptoms usually subside within 3 to 10 days after onset, and the disease is usually self-limiting.

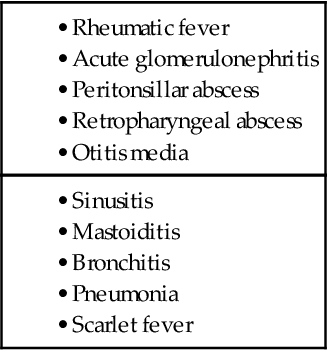

Bacterial pharyngitis caused by group A streptococcal infection can lead to serious complications (Table 33-1), including acute glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever carditis. Acute glomerulonephritis may occur 7 to 10 days after the acute infection, and rheumatic fever may develop 3 to 5 weeks after the acute infection.

Many types of rapid antigen tests (RATs) and screens for group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal antigen are available. These tests vary in specificity and sensitivity and cost about the same as a culture and sensitivity, but the results are available in less than 15 minutes. Two common tests are the Gen-Probe and the Optical Immunoassay (OIA).

In some cases, throat cultures can be important in distinguishing viral from a group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection; however, the results are not entirely accurate. False-negative cultures can occur, and 24 to 48 hours are required for results.

With either RAT or culture methods, it is essential to obtain throat specimens properly for an accurate test result. The organisms are not uniformly distributed throughout the throat and can be missed during swabbing. To obtain a specimen, rub a sterile cotton swab from a throat culture kit first over the right tonsillar area, moving across the right arch, the uvula, and then across the left arch to the left tonsillar area (Rushing, 2007). Remove the swab without touching the patient’s teeth, tongue, or gums. Place the swab back into the tube, cap it, and then crush the glass ampule in the culture tube. Send it to the laboratory as quickly as possible.

A complete blood count (CBC) is performed when the patient’s condition is severe or does not improve. Patients who need a CBC are those who have high fevers, lethargy, or manifestations of complications.

Ask about the patient’s recent contacts (within the past 10 days) with people who have been ill. Specifically ask whether he or she has been ill with symptoms of a cold or upper respiratory tract infection recently. Document any history of streptococcal infections, rheumatic fever, valvular heart disease, or penicillin allergy. Because diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) can cause pharyngitis, ask about and document whether the patient has had a diphtheria immunization.

Interventions

Most sore throats in adults are viral, do not require antibiotic therapy, and respond to supportive interventions. Teach the patient to rest, increase fluid intake, humidify the air, and use analgesics for pain. Gargling several times each day with warm saline and using throat lozenges can increase comfort.

Management of bacterial pharyngitis involves antibiotics and the same supportive care as with viral pharyngitis. For streptococcal infection, an oral penicillin or cephalosporin is prescribed. Drugs from the macrolide class (e.g., azithromycin or erythromycin) are used if the patient is allergic to penicillin.

The patient should be re-evaluated if there is no improvement in 3 days or if manifestations are still present after completion of the antibiotic course. Persistent bacterial pharyngitis may occur with immunosuppression. Any patient whose bacterial pharyngitis does not improve with antibiotics should consider human immune deficiency virus (HIV) testing.

A rare complication of pharyngitis in adults is infection of the epiglottis and supraglottic structures (epiglottitis). The epiglottis is a flaplike structure that closes over the trachea during swallowing to prevent aspiration. An inflamed epiglottis can swell and obstruct the airway, causing an emergency that inhibits oxygenation and tissue perfusion.

Teach the patient how to take his or her temperature accurately every morning and evening until the infection resolves. He or she is not contagious after 24 hours of effective antibiotic therapy. Family members or close contacts who also have a sore throat should be evaluated.

Tonsillitis

Pathophysiology

Tonsillitis is an inflammation and infection of the tonsils and lymphatic tissues located on each side of the throat. The tonsils are lymphatic tissue shaped like a small almond. They are covered by mucous membranes and have small valleys (crypts) across their surface. Tonsils filter organisms and protect the respiratory tract from infection (McCance et al., 2010).

Tonsillitis is a contagious airborne infection. Acute or chronic tonsillitis can occur in any age-group, but it is less common in adults. The disease usually lasts 7 to 10 days and often is caused by bacteria, most commonly Streptococcus. Other bacterial causes include Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pneumococcus. Viruses also cause tonsillitis. Chronic tonsillitis may result from an unresolved acute infection or recurrent infections.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Chart 33-3 lists the manifestations of acute tonsillitis. Diagnostic tests often used to rule out other causes of the sore throat and fever include a rapid antigen test (RAT), CBC, throat culture and sensitivity (C&S) studies, and Monospot test. If respiratory symptoms are present, chest x-rays may be needed. The WBC count usually is elevated in bacterial infections and normal in viral infections.

Antibiotics (usually penicillin or azithromycin) are prescribed for 7 to 10 days. Nursing priorities include teaching the patient about supportive care and stressing the importance of completing antibiotic therapy. Teach him or her to rest, increase fluid intake, humidify the air, use analgesics for pain, gargle several times each day with warm saline, and use throat lozenges.

Surgical intervention for tonsillitis may be needed for recurrent acute infections (especially group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections), chronic infections that do not respond to antibiotics, a peritonsillar abscess, and enlarged tonsils or adenoids that obstruct the airway. It is usually performed after the patient has recovered from an acute tonsillitis and no infection is present (except with an acute peritonsillar abscess). The procedure may involve complete tonsil removal (for chronic infection) or a partial tonsil removal for obstruction without infection. A variety of techniques are used to remove tonsils from adults; however, the dissection and snare technique is still the most common. The adenoids may be removed at the same time. When the patient is an adult, a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A) is usually performed with him or her under general anesthesia. After surgery, nursing interventions focus on assessing for airway clearance, providing pain relief, and monitoring for excessive bleeding.

Peritonsillar Abscess

Peritonsillar abscess (PTA) is a complication of acute tonsillitis. The infection spreads from the tonsil to the surrounding tissue, which forms an abscess. The most common cause of PTA is group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus.

Manifestations include pus behind the tonsil causing one-sided swelling with deviation of the uvula toward the unaffected side. The patient may drool, have severe throat pain radiating to the ear, have a voice change, and have difficulty swallowing. He or she may also have a tonic contraction of the muscles of chewing (trismus) and have difficulty breathing. Bad breath is present, and lymph nodes on the affected side are swollen. An intraoral or transcutaneous ultrasound may be used for diagnosis (Hoyle, 2009).

Outpatient management with antibiotic therapy and percutaneous needle aspiration of the abscess is usually needed. Acute care management may include IV opioid analgesics for severe pain and IV steroids to reduce the swelling. The patient usually improves in 36 hours. Stress the importance of completing the antibiotic regimen and of coming to the emergency department quickly if symptoms of obstruction appear (drooling and stridor). Teach him or her about comfort measures (e.g., warm saline gargles or irrigations, an ice collar, analgesics). Hospitalization is required when the airway is in jeopardy or when the infection does not respond to antibiotic therapy. Incision and drainage of the abscess and additional antibiotic therapy may be needed. A tonsillectomy may be performed to prevent recurrence.

Disorders of the Larynx and Lungs

Laryngitis

Laryngitis is an inflammation of the mucous membranes lining the larynx and may or may not include edema of the vocal cords. It can occur as a single problem or occur with upper respiratory infections. Laryngitis also can be a manifestation of other problems, such as throat or lung cancer. Common causes include exposure to irritating inhalants (e.g., chemical fumes, tobacco, alcohol, smoke), voice overuse, inhalation of fumes (e.g., glue, paint thinner, butane), or intubation. Recurrent laryngitis may be caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Assess the patient for hoarseness, dry cough, and difficulty swallowing. Complete but temporary voice loss (aphonia) also may occur. A laryngeal mirror is used by a physician or advanced practice nurse to inspect the larynx and identify inflammation, polyps, edema, or tumor. If suspicious lesions are present, an x-ray, computed tomography, or fiberoptic laryngoscopic examination may be needed. Patients who may have a disorder other than acute laryngitis are referred to an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist (otolaryngologist).

Nursing management focuses on symptom relief and prevention. Treatment consists of voice rest, steam inhalations, increased fluid intake, and throat lozenges. Antibiotic therapy and bronchodilators are prescribed when sinusitis, bronchitis, or other bacterial infection is also present. Teach the patient and family about relief measures, infection prevention, and avoidance of alcohol, tobacco, and pollutants, which can irritate the larynx.

Teach about preventive strategies such as reducing tobacco and alcohol use. Emphasize the need to avoid activities that place an added strain on the larynx, such as singing, cheering, public speaking, heavy lifting, and whispering. Speech-language therapy is used when vocal cord injury occurs with laryngitis. Further evaluation is needed for recurrent bouts of laryngitis.

Seasonal Influenza

Pathophysiology

Seasonal influenza, or “flu,” is a highly contagious acute viral respiratory infection that can occur in adults of all ages. Epidemics are common and lead to complications of pneumonia or death, especially in older adults or debilitated or immunocompromised patients. Between 5% and 20% of the U.S. population develop influenza each year, and more than 36,000 deaths per year are caused by it (Kapustin, 2008). Hospitalization may be required. Influenza may be caused by one of several virus families, referred to as A, B, and C.

The patient with influenza often has a severe headache, muscle aches, fever, chills, fatigue, and weakness. Adults are contagious from 24 hours before symptoms occur and up to 5 days after they begin. Patients who are immunosuppressed may be contagious for several weeks. Sore throat, cough, and watery nasal discharge generally follow the initial symptoms for a week or longer. Most patients feel fatigued for 1 to 2 weeks after the acute episode has resolved.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Vaccinations for the prevention of influenza are widely available. The vaccine is changed every year on the basis of which specific viral strains are most likely to pose a problem during the influenza season (i.e., late fall and winter). Usually, the vaccines contain three antigens for the three expected viral strains (trivalent influenza vaccine [TIV]). Influenza vaccinations can be taken as an IM injection (Fluviron, Fluzone) or as a live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) by intranasal spray (FluMist). An attenuated virus is a live virus that has been altered to reduce its ability to cause an infection. The intranasal vaccine is live, and some people develop influenza symptoms after its use. It is recommended only for healthy people up to 49 years of age. People recommended to be vaccinated yearly include those older than 50 years, people with chronic illness or immune compromise, those living in institutions, people living with or caring for adults with health problems that put them at risk for severe complications of influenza, and health care personnel providing direct care to patients (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010c).

Teach the patient who is sick to reduce the risk for spreading the flu by thoroughly washing hands, especially after nose blowing, sneezing, coughing, rubbing the eyes, or touching the face. Other precautions include staying home from work, school, or places where people gather; covering the mouth and nose with a tissue when sneezing or coughing; disposing properly of used tissues immediately; and avoiding close contact with other people (e.g., kissing, hugging, handshaking). Although handwashing is a good method to prevent transmitting the virus in droplets from sneezing or coughing, many people cannot wash their hands as soon as they have coughed or sneezed. The technique recommended by the CDC for controlling flu spread is to sneeze or cough into the upper sleeve rather than into the hand (CDC, 2010a). (Respiratory droplets on the hands can contaminate surfaces and be transmitted to other people.)

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Viral infections do not respond to traditional antibiotic therapy. Antiviral agents may be effective for prevention and treatment of some types of influenza. Amantadine (Symmetrel) and rimantadine (Flumadine) have been effective in the prevention and treatment of influenza A, although strains of resistant organisms are increasing. Ribavirin (Virazole) has been used for severe influenza B. Two drugs that may shorten the duration of influenza A and influenza B are zanamivir (Relenza), which is used as an oral inhalant, and oseltamivir (Tamiflu), which is an oral tablet. These drugs prevent viral spread in the respiratory tract by inhibiting a viral enzyme (neuraminidase) that allows the virus to penetrate respiratory cells. To be effective, they must be taken within 24 to 48 hours after the onset of manifestations.

Advise the patient to stay in bed for several days and increase fluid intake unless another problem requires fluid restriction. Saline gargles may ease sore throat pain. Antihistamines may reduce the rhinorrhea. Other supportive measures are the same as those for acute rhinitis.

Pandemic Influenza

Pathophysiology

Many viral infections among animals and birds are not usually transmitted to humans. A few notable exceptions have occurred when these animal and bird viruses mutated and became highly infectious to humans. These infections are termed pandemic because they have the potential to spread globally. Such pandemics include the 1918 “Spanish” influenza that resulted in at least 40 million deaths worldwide and perhaps as many as 100 million deaths. This virus, the H1N1 strain, also known as “swine flu,” mutated and became highly infectious to humans. Most recently, the 2009 H1N1 influenza A resulted in a pandemic infection that spread to 215 countries. In the United States, the number of people infected with this virus during the pandemic is estimated at 61 million, resulting in more than 12,000 deaths (CDC, 2010b). A vaccine was developed in 2009 as a single antigen (monovalent) and was administered separately from the seasonal influenza vaccine. For the 2010-2011 influenza season, the trivalent seasonal vaccine contained the H1N1 antigen.

A new avian virus is the H5N1 strain, known as “avian influenza” or “bird flu,” that has infected millions of birds, especially in Asia, and now has started to spread by human-to-human contact. World health officials are concerned that this strain could become a pandemic because humans have essentially no naturally occurring immunity to this virus. Thus the infection could lead to a worldwide pandemic with very high mortality rates.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

The prevention of a worldwide influenza pandemic of any virus is the responsibility of everyone. Health officials have been monitoring the situation with human outbreaks and with testing of both wild and domestic bird species throughout the world. Vaccines currently are available for both H1N1 and H5N1; however, the H5N1 vaccine is stockpiled and not part of general influenza vaccination. The recommended early approach to disease prevention with H5N1 is early recognition of new cases and the implementation of community and personal quarantine and social-distancing behaviors to reduce exposure to the virus.

Plans for prevention and containment in North America have been developed with the cooperation of most levels of government. When a cluster of cases is discovered in an area, the stockpiled vaccine is to be made available for immunizations. Because vaccination with this vaccine is a two-step process with the first IM injection followed 28 days later by a second IM injection, additional prevention measures are needed.

The antiviral drugs oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) should be widely distributed. These drugs are not likely to prevent the disease but may reduce the severity of the infection and reduce the mortality rate. The infected patients should be cared for in strict isolation. All nonessential public activities in the area should be stopped. These include public gatherings of any type, attendance at schools, religious services, shopping, and many types of employment. People should stay home and use their emergency preparedness supplies (food, water, and drugs) they have stockpiled for at least 2 weeks (see Chapter 12). Travel to and from the affected area should be stopped.

Urge all people to pay attention to public health announcements and early warning systems for disease outbreaks. Teach them the importance of starting prevention behaviors immediately upon notification of an outbreak. Teach all people to have a minimum of a 2-week supply of all their prescribed drugs and at least a 2-week supply of nonperishable food and water for each member of the household. They should also have a battery-powered radio (and batteries) to keep informed of updates in an active prevention situation. See Chapter 12 for more information on items to have ready in the home for disaster preparedness. An influenza pandemic is a disaster, and containing it requires the cooperation of all people.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Care of the patient with avian influenza focuses on supporting the patient and preventing spread of the disease. Both are equally important. The initial manifestations of avian influenza are similar to other respiratory infections—cough, fever, and sore throat. These progress rapidly to shortness of breath and pneumonia. In addition, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and bleeding from the nose and gums occur. Ask any patient with these symptoms if he or she has recently (within the past 10 days) traveled to areas of the world affected by H5N1. If such travel has occurred, coordinate with the health care team to place the patient in an airborne isolation room with negative air pressure. These precautions remain until the diagnosis of H5N1 is ruled out or the threat of contagion is over. Diagnosis is made based on clinical manifestations and positive testing. The most rapid test currently approved for testing of H5N1 is the AVantage A/H5N1 Flu Test. It can detect a specific protein (NS1), which indicates the presence of H5N1, from nasal or throat swabs in less than 40 minutes.

When providing care to the patient with avian influenza, personal protective equipment is essential. Coordinate the protection activity by ensuring that anyone entering the patient’s room for any reason wears a fit-tested respirator or a standard surgical mask (“Lessons Learned,” 2010). Use other Airborne Precautions and Contact Precautions as described in Chapter 25. Teach others to self-monitor for disease symptoms, especially of respiratory infection, for at least a week after the last contact with the patient. Use the antiviral drug oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza) within 48 hours of contact with the infected patient. All health care personnel working with patients suspected of having avian influenza are recommended to receive the vaccine in the recommended two-step process.

No effective treatment for this infection currently exists. Antibiotics and antiviral drugs cannot kill the virus or prevent its replication. Interventions are supportive to allow the patient’s own immune system to fight the infection. Oxygen is given when hypoxia or breathlessness is present. Respiratory treatments to dilate the bronchioles and move respiratory secretions are used. If hypoxemia is not improved with oxygen therapy, intubation and mechanical ventilation may be needed. Antibiotics are used to treat a bacterial pneumonia that may occur with H5N1.

In addition to the need for respiratory support, the patient with H5N1 may have severe diarrhea and need fluid therapy. The Transmission Precautions may prevent the use of a scale to determine fluid needs by weight changes. Monitor the patient’s hydration status, and carefully measure intake and output. The type of fluid therapy varies with the patient’s cardiovascular status and the osmolarity of the blood. The two most important areas to monitor during rehydration are pulse rate and quality and urine output.

Pneumonia

Pathophysiology

Pneumonia is an excess of fluid in the lungs resulting from an inflammatory process. The inflammation is triggered by many infectious organisms and by inhalation of irritating agents. Infectious pneumonias are categorized as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) or health care–associated pneumonia (known as HAP or HAI), depending on where the patient was exposed to the infectious agent (Dobbins & Howard, 2011). HAPs are more likely to be resistant to some antibiotics than are CAPs.

The inflammation occurs in the interstitial spaces, the alveoli, and often the bronchioles. The process begins when organisms penetrate the airway mucosa and multiply in the alveoli. White blood cells (WBCs) migrate to the area of infection, causing local capillary leak, edema, and exudate. These fluids collect in and around the alveoli, and the alveolar walls thicken. Both events seriously reduce gas exchange and lead to hypoxemia, interfering with oxygenation and possibly leading to death. Red blood cells (RBCs) and fibrin also move into the alveoli. The capillary leak spreads the infection to other areas of the lung. If the organisms move into the bloodstream, sepsis results; if the infection extends into the pleural cavity, empyema (a collection of pus in the pleural cavity) results.

The fibrin and edema of inflammation stiffen the lung, reducing compliance and decreasing the vital capacity. Alveolar collapse (atelectasis) further reduces the ability of the lung to oxygenate the blood moving through it. As a result, arterial oxygen levels fall, causing hypoxemia.

Pneumonia may occur as lobar pneumonia with consolidation (solidification, lack of air spaces) in a segment or an entire lobe of the lung or as bronchopneumonia with diffusely scattered patches around the bronchi. The extent of lung involvement after the organism invades depends on the host defenses. Bacteria multiply quickly in a person whose immune system is compromised. Tissue necrosis results when an abscess forms and perforates the bronchial wall.

Etiology

Pneumonia develops when the immune system cannot combat the virulence of the invading organisms. Organisms from the environment, invasive devices, equipment and supplies, staff, or other people can invade the body. Risk factors are listed in Table 33-2. Pneumonia can be caused by bacteria, viruses, mycoplasmas, fungi, rickettsiae, protozoa, and helminths (worms). Noninfectious causes of pneumonia include inhalation of toxic gases, chemical fumes, and smoke and aspiration of water, food, fluid, and vomitus.

TABLE 33-2