Chapter 25 Care of Patients with Infection

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Explain the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hand hygiene recommendations for health care workers.

2. Describe infection control methods, such as hand hygiene and Transmission-Based Precautions.

3. Apply current principles of infection prevention and control.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

6. Identify patients most at risk for infection, including older adults.

7. Provide information to patient and family about drug therapy for infections.

8. Identify common clinical manifestations of infectious diseases.

9. Interpret laboratory test findings related to infections and infectious diseases.

10. Evaluate nursing interventions for management of the patient with an infection.

11. Explain why multidrug-resistant organisms are increasing.

12. Identify common emerging diseases and their basic clinical management.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview of the Infectious Process

Transmission of Infectious Agents

Transmission of infection in health care requires three factors:

Host factors influence the development of infection (Table 25-1). Host defenses provide the body with an efficient system for protection against pathogens. Breakdown of these defense mechanisms may increase the susceptibility (risk) of the host for infection.

TABLE 25-1 HOST FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE DEVELOPMENT OF INFECTION

| HOST FACTOR | INCREASED RISK FOR INFECTION |

|---|---|

| Natural immunity | Congenital or acquired immune deficiencies |

| Normal flora | Alteration of normal flora by antibiotic therapy |

| Age | Infants and older adults |

| Hormonal factors | Diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid therapy, and adrenal insufficiency |

| Phagocytosis | Defective phagocytic function, circulatory disturbances, and neutropenia |

| Skin/mucous membranes/normal excretory secretions | Break in skin or mucous membrane integrity; interference with flow of urine, tears, or saliva; interference with cough reflex or ciliary action; changes in gastric secretions |

| Nutrition | Malnutrition or dehydration |

| Environmental factors | Tobacco and alcohol consumption and inhalation of toxic chemicals |

| Medical interventions | Invasive therapy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and steroid therapy; surgery |

Immunity is resistance to infection; it is usually associated with the presence of antibodies or cells that act on specific microorganisms. Passive immunity is of short duration (days or months) and either natural by transplacental transfer from the mother or artificial by injection of antibodies (e.g., immunoglobulin). Active immunity lasts for years and is natural by infection or artificial by stimulation of the body’s immune defenses (e.g., vaccination). Chapter 19 discusses the immune system and immunity in detail.

Environmental factors can also influence patients’ immune status and thus their susceptibility to or ability to fight infection. Examples include alcohol consumption, nicotine use, inhalation of bone marrow–suppressing toxic chemicals, and certain vitamin deficiencies. Malnutrition, especially protein-calorie malnutrition, places patients at increased risk for infection. Diseases such as diabetes mellitus also predispose a patient to infection. Older adults have decreased immune systems, as well as other physiologic changes that make them very susceptible to infection (Chart 25-1).

Chart 25-1 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult

Factors That May Increase Risk for Infection in the Older Patient

| Factor | Aging-Associated Changes or Conditions |

Microorganisms can gain direct access to the bloodstream, especially when invasive devices or tubes are used. The incidence of bloodstream infections (BSIs) continues to increase in hospitals throughout the United States. Central venous catheters (CVCs) are a primary cause of these infections (see Chapter 15 for more discussion of CVC-related BSIs). In the community setting, biting insects can inject organisms into the bloodstream, causing infection (e.g., Lyme disease, West Nile viral encephalitis).

Indirect transmission may involve contact with infected secretions or droplets. Droplets are produced when a person talks or sneezes; the droplets travel short distances. Susceptible hosts may acquire infection by contact with droplets deposited on the nasal, oral, or conjunctival membranes. Therefore the CDC recommends that staff stay at least 3 feet (1 m) away from a patient with droplet infection (Siegel et al., 2007). An example of droplet-spread infection is influenza. Unlike airborne droplet nuclei, discussed later, droplets do not stay suspended in the air.

Preventing the spread of microbes that are transmitted by the airborne route requires the use of special air handling and ventilation systems in an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR). M. tuberculosis and the varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox) are examples of airborne agents that require one of these systems. In addition to the AIIR, respiratory protection using certified N95 or higher level respirator masks is recommended for health care personnel entering the patient’s room (Siegel et al., 2007). The N95 rating means that at least 95% of the inhaled air is filtered.

Physiologic Defenses for Infection

Inflammation is another important nonspecific defense mechanism for preventing the spread of infection. It occurs when tissue becomes damaged. Damaged cells release enzymes, and polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes (neutrophils) are attracted to the infected site from the bloodstream. One important substance, histamine, increases the permeability of the capillaries in inflamed tissues, thus allowing fluid, proteins, and white blood cells to enter an inflamed area. Other enzymes activate fibrinogen, which causes leaked fluid to clot and prevents its flow away from the damaged site into unaffected tissue, essentially “walling off” the inflamed tissue. The process of phagocytosis disposes of the invading microorganism and often dead tissue. If inflammation is caused by infection, the end products of inflammation form pus, which is then absorbed or exits the body through a break in the skin. Chapter 19 discusses the process of inflammation in more detail.

Specific defense responses to specific microorganisms are provided by the antibody- and cell-mediated immune systems. The antibody-mediated immune system produces antibodies directed against certain pathogens. These antibodies inactivate or destroy invading microorganisms as well as protect against future infection from that microorganism. Resistance to other microorganisms is mediated by the action of specifically sensitized T-lymphocytes and is called cell-mediated immunity. The components of the immune system work both independently and together to protect against infection. Chapter 19 describes the function of the immune system in detail.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Infection Control in Inpatient Health Care Agencies

Infections occur most often in high-risk patients, such as older adults and those who have inadequate immune systems (immunocompromised). Implement interventions to prevent infection and detect signs and symptoms as early as possible. Chart 25-2 summarizes nursing interventions for infection prevention and control.

Chart 25-2 Best Practices for Patient Safety and Quality Care

The Patient at Risk for Infection

• Assess patients for risk for infections.

• Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection.

• Monitor laboratory tests results, such as cultures and white blood cell (WBC) count and differential.

• Screen all visitors for infections or infectious disease.

• Inspect skin and mucous membranes for redness, heat, pain, swelling, and drainage.

• Promote sufficient nutritional intake, especially protein for healing.

• Encourage fluid intake to treat fever.

• Teach the patient and family the signs and symptoms of infections and when to report them to the health care provider.

• Teach the patient and family how to avoid infections in health care agencies and the community.

Infection acquired in the inpatient health care setting (not present or incubating at admission) is termed a health care–associated infection (HAI). When occurring in a hospital setting, they are sometimes referred to as hospital-acquired infections, but the former term is more accurate. HAIs can be endogenous (from a patient’s flora) or exogenous (from outside the patient, often from the hands of health care workers, tubes, or implants). Therefore use of the less popular term nosocomial infection does not imply that an infection was caused by health care (or poor health care delivery) but only that it occurred while receiving health care. HAIs, including surgical-site infections (SSIs), occur in 1 in 20 inpatients yearly, causing increased health care costs and many deaths (see discussion of SSIs in Chapter 18). These infections tend to occur most often because health care workers do not follow basic infection control principles, especially aseptic technique and injection practices (Siegel et al., 2007).

Infection control within a health care facility is designed to reduce the risk for HAIs and thus reduce morbidity and mortality, as recommended in The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs). This expected outcome is consistent with the desire for health care facilities to create a culture of safety within their environments (see Chapter 1). Infection control and prevention is a collaborative effort and includes:

• Facility- and department-specific infection control policies and procedures

• Community and interdisciplinary collaboration

• Product evaluation with an emphasis on quality and cost savings

• Bioengineering for designing health care facilities that help control the spread of infections

Methods of Infection Control

Health care workers’ hands are the primary way in which infection is transmitted from patient to patient or staff to patient. Hand hygiene refers to both handwashing and alcohol-based hand rubs (ABHRs) (“hand sanitizers”). There is a lack of rigorous evidence linking which specific hand hygiene recommendations best prevent health care–associated infections (HAIs) (Backman et al., 2008).

In 2002, the CDC released a document entitled “CDC Hand Hygiene Recommendations.” These recommendations are summarized in Chart 25-3. Handwashing is still an important part of hand hygiene, but it is recognized that in some health care settings, sinks may not be readily available. Despite years of education, health care workers often find it difficult to leave the patient care setting to wash their hands and do not perform hand hygiene on a consistent basis.

Chart 25-3 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Hand Hygiene

• When hands are visibly soiled or contaminated with proteinaceous material or are visibly soiled with blood or other body fluids, wash hands with soap and water.

• If hands are not visibly soiled, use an alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) for decontaminating hands or wash hands with soap and water.

• Use either ABHR or wash with soap and water (decontaminate hands) before having direct contact with patients.

• Decontaminate hands before donning sterile gloves to perform a procedure, such as inserting an invasive device (e.g., indwelling urinary catheter).

• Decontaminate hands after contact with a patient’s intact skin (e.g., taking a pulse) or with body fluids or excretions/secretions.

• Decontaminate hands after removing gloves.

• Decontaminate hands after contact with inanimate objects (including medical equipment) in the immediate vicinity of the patient.

Action Alert

The CDC guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2002) also address the issue of artificial fingernails, which have been linked to a number of outbreaks due to poor fingernail health and hygiene. The guidelines recommend that artificial fingernails and extenders not be worn while caring for patients at high risk for infections, such as those in ICUs or operating suites. Most health care agencies have banned artificial nails for all health care workers providing direct patient care and require that natural nails be short and without nail polish.

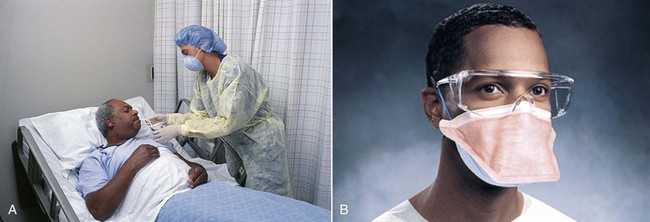

Personal protective equipment (PPE) refers to the use of gloves, isolation gowns, face protection (masks, goggles, face shields), and respirators with N95 or higher filtration (Fig. 25-1).

Action Alert

Adequate staffing of nurses is an essential method for preventing infection (Stone et al., 2008). In addition to a ratio of one infection control practitioner (ICP) to 100 occupied acute care beds, nurse staffing is critical. The CDC recommends that two methods to ensure adequate infection control (IC) be implemented (Siegel et al., 2007). First, an infection control nurse liaison should be designated on every unit of an inpatient facility. This nurse is responsible for implementing new IC policies, increasing staff IC compliance through education, and collaborating with the facility’s ICP to monitor for infections. Second, bedside nurse staffing should consists of full-time nurses assigned regularly to the unit rather than float, pool, or agency nurses. Studies have found that infection rates increase when float, pool, or agency nurses are substituted for full-time, regular staff (Siegel et al., 2007).

Patient placement has been used as a way to reduce the spread of infection. Some studies have suggested that private patient rooms help decrease infections. However, the CDC has not mandated that all patients, even those with infections, have a private room. The CDC does recommend that private rooms always be used for patients on Airborne Precautions and those in a protective environment (PE). A PE is architecturally designed and structured to prevent infection from occurring in patients who are at extremely high risk, such as those having stem cell therapy. The CDC also prefers private rooms for patients who are on Contact and Droplet Precautions (Siegel et al., 2007). Many hospitals are increasing their number of private rooms, and some are becoming totally private-room facilities. Large health care systems often have biomedical engineers to assist in designing the best environment to reduce the spread of infection, including ventilation systems and physical layout.

Infection control principles for patient transport include limiting movement to other areas of the facility, using appropriate barriers like covering infected wounds, and notifying other departments or agencies who are receiving the patient about the necessary precautions (Siegel et al., 2007). Complete and accurate hand-off communication between agencies is also very important to prevent the spread of infection, according to The Joint Commission’s NPSGs.

Safe and Effective Care Environment

A. “I will wash my hands after direct client care.”

B. “I will wear gloves when emptying the Foley bag.”

C. “I don’t need to wash my hands if I wear gloves.”

D. “I will use a hand sanitizer when I can’t wash my hands.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree