Chapter 21 Care of Patients with HIV Disease and Other Immune Deficiencies

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Use appropriate techniques to reduce the risk for infection in an immunosuppressed patient.

2. Use Standard Precautions to prevent human immune deficiency virus (HIV) transmission to you, patients, and other members of the health care team.

3. Ensure that confidentiality of HIV status is maintained by all health care team members.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

4. Teach all sexually active people to use safer sex practices.

5. Assess all patients for high-risk behaviors for HIV disease.

6. Teach family members reorientation techniques to use when the patient is confused.

7. Respect the patient’s right to inform or not to inform family members about his or her HIV status.

8. Use a nonjudgmental approach when discussing sexual practices, sexual behaviors, and recreational drug use.

9. Compare primary and secondary immune deficiencies for cause and onset of problems.

10. Explain the differences in nursing care required for a patient with a pathogenic infection versus a patient with an opportunistic infection.

11. Distinguish between the conditions of HIV infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) for clinical manifestations and risks for complications.

12. Describe the ways in which HIV is transmitted.

13. Coordinate nursing care for the patient with AIDS who has impaired gas exchange.

14. Identify teaching priorities for the HIV-positive patient receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Acquired (Secondary) Immune Deficiencies

HIV InFection and AIDS

Pathophysiology

Human immune deficiency virus (HIV) infection can progress to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which is the most common secondary immune deficiency disease in the world (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). First identified in 1981, HIV/AIDS is now a serious worldwide epidemic.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

The HIV Infectious Process

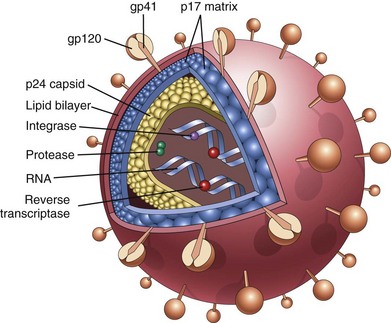

Viral particle features include an outer envelope with special “docking proteins,” known as gp41 and gp120, that assist in finding a host (Fig. 21-1). Inside, the virus has two protein coatings and the genetic material along with the enzymes reverse transcriptase (RT) and integrase. The first challenge is for the HIV particle to get inside a host cell. HIV accomplishes this task by first finding a way into the host’s bloodstream. Once in the blood, HIV “hijacks” certain cells. One of the cells that it hijacks is the CD4 T-cell, also known as the CD4 cell, helper/inducer T-cell, or T4-cell (Kaufman, 2011) (see Chapter 19). This cell directs immune system defenses and regulates the activity of all immune system cells. If HIV successfully enters a CD4 T-cell, it can then create more virus particles.

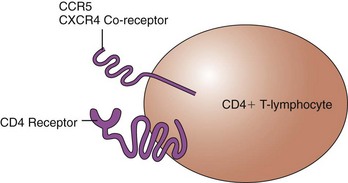

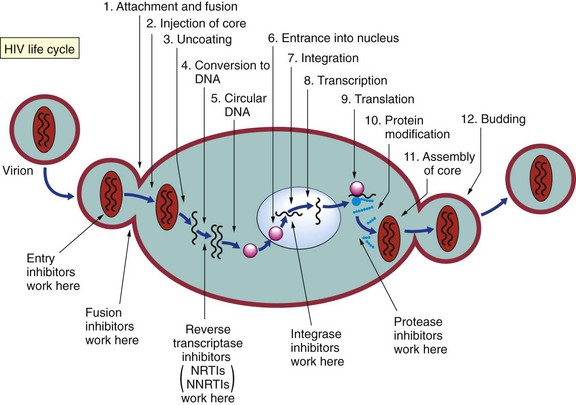

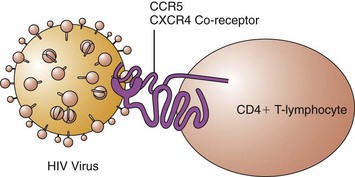

Virus-host interactions are needed for disease development. When a person is infected with HIV, the virus randomly “bumps” into many cells. The docking proteins on the outside of the virus try to find special receptors on a host cell that will allow the virus to bind and then enter the cell. The CD4+ T-cell has receptors on its surface known as CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 (Fig. 21-2). Proteins on the HIV particle surface, known as gp120 and gp41, recognize these receptors on the CD4+ T-cell. For the virus to enter this cell, both the gp120 and the gp41 must bind to the receptors. The gp120 first binds to the primary CD4 receptor, which changes its shape and allows the gp41 to bind to one of the co-receptors (either the CCR5 receptor or the CXCR4 receptor). This attachment allows the virus to then enter the CD4+ T-cell (Fig. 21-3). Viral binding to the CD4 receptor and to either of the co-receptors is needed to enter the cell. (The new drug class known as entry inhibitors works here to block the receptor and prevent the interaction needed for entry of HIV into the CD4+ T-cell.)

FIG. 21-3 The successful interaction of the HIV “docking” proteins with the CD4+ T-lymphocyte receptors.

HIV particles are made within the infected CD4+ T-cell, using all the metabolic machinery of the host. The new virus particle is made in the form of one long protein strand. The strand is clipped, using chemical enzyme scissors called HIV protease, into several small functional pieces. These pieces are formed into a new finished viral particle. (The drug class known as protease inhibitors works here to inhibit HIV protease.) Once the new virus particle is finished, it fuses with the infected cell’s membrane and then buds off in search of another CD4+ T-cell to infect (Fig. 21-4).

• Lymphocytopenia (decreased numbers of lymphocytes)

• Increased production of incomplete and nonfunctional antibodies

HIV Classification

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in a 1993 definition, classified HIV infection by correlating clinical conditions with three ranges of CD4+ T-cell counts. This classification was replaced in 2008 by defining four stages of the disease. In this new definition, laboratory confirmation of HIV infection (by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and Western blot analysis) plus CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or percentage and the presence or absence of the 26 AIDS-defining conditions (Table 21-1) determine the classification (CDC, 2008). The person with HIV infection can transmit the virus to others at all stages of disease, but the recently infected person with a high viral load and those at end stage without drug therapy can be particularly infectious.

• Stage 1 CDC Case Definition describes any patient with confirmed HIV infection and a CD4+ T-cell count of greater than 500 cells/mm3 or a CD4+ T-cell percentage of 29% or greater. A person at this stage has no AIDS-defining illnesses.

• Stage 2 CDC Case Definition describes any patient with a confirmed HIV infection and a CD4+ T-cell count between 200 and 499 cells/mm3 or a CD4+ T-cell percentage between 14% and 28%. A person at this stage has no AIDS-defining illnesses.

• Stage 3 CDC Case Definition describes any patient with a confirmed HIV infection and a CD4+ T-cell count of less than 200 cells/mm3 or a CD4+ T-cell percentage of less than 14%. A person who has higher CD4+ T-cell counts or percentages but who also has a documented AIDS-defining illness meets the requirements of Stage 3 CDC Case Definition.

• Stage 4 CDC Case Definition is used to describe any patient with a confirmed HIV infection, but no information regarding CD4+ T-cell counts, CD4+ T-cell percentages, and AIDS-defining illnesses is available.

TABLE 21-1 CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION CLASSIFICATION OF AIDS-DEFINING CONDITIONS IN ADULTS

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Recommendations and reports: Appendix A—AIDS-defining conditions. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(RR-10), 9.

Incidence/Prevalence

Since the beginning of the epidemic in the United States, more than 1.2 million cases of HIV/AIDS have been diagnosed, and more than 617,025 people have died of AIDS. Currently, more than 600,000 people in the United States are living with HIV/AIDS (CDC, 2011). This number is less than the total number of people in the United States estimated to be infected with HIV (1.1 million to 1.8 million). Worldwide, about 40 to 60 million people are currently infected with HIV, at least 30 million deaths from AIDS have occurred, and 33 million people are living with AIDS (WHO, 2010).

Most AIDS cases in North America occur among men who have had sex with other men (MSM) (53%) or individuals of either gender who have used injection drugs (16%) (CDC, 2011). The changing demographics of the infection indicate that the perception that HIV/AIDS is only a problem for homosexual white men is false (Kirton, 2011).

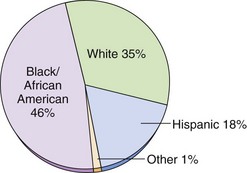

Most new HIV infections reported in the United States occur in racial and ethnic minority groups, particularly among Blacks/African Americans and Hispanics (CDC, 2011) (Fig. 21-5). These two groups show an increasing trend in HIV infection compared with a leveling off among white people. Factors that may increase the incidence of HIV infection and progression to AIDS among minority groups include:

• Fear of or lack of faith in the U.S. health care system

• Poverty and limited access to high-cost drugs

• Homophobia leading to increased bisexual activity among men of color

Considerations for Older Adults

Infection with HIV can occur at any age. Assess the older patient for risk behaviors, including a sexual and drug use history (Tangredi et al., 2008). Age-related decline in immune function increases the likelihood that the older adult will develop the infection after an HIV exposure. In the older woman, thinning of vaginal tissue as a result of decreased estrogen may increase susceptibility to all sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV infection. Cognitive deficits appear to occur earlier in the older adult with HIV (Vance, 2010).

Women are the fastest growing group with HIV infection and AIDS. In North America, about 16% of people with HIV infection are women. Twenty-five percent of newly diagnosed cases are women. In less affluent countries, 50% of cases occur in women (WHO, 2010). Risk factors are sexual exposure (75%) and injection drug use (25%). Strategies specifically targeted to reducing sexual exposures of HIV to women may help prevent an increase in HIV infection in that group. Women with HIV infection have a poorer outcome with shorter mean survival time than that of men. This outcome may be the result of late diagnosis and social or economic factors that reduce access to medical care.

AIDS is a disease with a high mortality rate. The fatality rate is at least 60% for adults and, to date, there is no cure (WHO, 2010). Thus a major focus for health care in North America and worldwide is prevention of HIV infection. For those infected with HIV, drug therapy slows disease progression and, to be effective, it must be taken as prescribed for the rest of the patient’s life.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

• Sexual: genital, anal, or oral sexual contact with exposure of mucous membranes to infected semen or vaginal secretions

• Parenteral: sharing of needles or equipment contaminated with infected blood or receiving contaminated blood products

• Perinatal: from the placenta, from contact with maternal blood and body fluids during birth, or from breast milk from an infected mother to child

Action Alert

Sexual Transmission

The CDC describes the ABC safer sex methods as A, abstinence; B, be faithful; and C, condoms (CDC, 2009b). Abstinence and mutually monogamous sex with a noninfected partner are the only absolutely safe methods of preventing HIV infection from sexual contact. Many forms of sexual expression can spread HIV infection if one partner is infected. The risk for becoming infected from a partner who is HIV positive is always present, although some sexual practices are more risky than others. The virus concentrates most heavily in blood and seminal fluid, although it is also present in vaginal secretions. Thus risk differs by gender, sexual act, and the viral load of the infected partner.

• A latex or polyurethane condom for genital and anal intercourse (Chart 21-1)

• A condom or latex barrier (dental dam) over the genitals or anus during oral-genital or oral-anal sexual contact

• Latex gloves for finger or hand contact with the vagina or rectum

Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Condom Use to Prevent Sexually Transmitted Diseases

• Use latex or polyurethane condoms rather than natural membrane condoms.

• Store condoms in a cool, dry place.

• Do not use condoms that were in damaged packages or those that show signs of age, such as those that are brittle, sticky, or discolored.

• Handle condoms carefully to avoid puncturing them.

• Put a condom on before making any genital contact.

• Hold the tip of the condom and unroll it onto the erect penis, making sure that no air is trapped in the tip. Leave space at the tip to collect semen.

• Use adequate lubrication. Use water-based lubricants only. Petroleum or oil-based lubricants such as petroleum jelly, cooking oil, shortening, and lotions can damage the condom.

• Replace a broken condom immediately. If ejaculation occurs after the condom breaks, there may be some protection in the immediate use of a spermicide.

• After ejaculation, the condom must remain on until the penis is withdrawn. While the penis is still erect, hold the condom against the base of the penis while withdrawing.

From Centers for Disease Control. (1988). Condoms for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 37(9), 133-137.

A promising area of research for prevention of sexual transmission is the use of vaginal gels that contain an antiretroviral agent (tenofovir or raltegravir). Early results indicate that if the gel is used before and after intercourse, new infections among women can be reduced by as much as 50% (Abdool Karim et al., 2010).

For those who believe they have been exposed to HIV as a result of sexual relations or other types of nonoccupational exposure, the CDC has guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis. The length and type of prophylaxis therapy depend on the nature of the exposure (Chart 21-2).

Chart 21-2 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis (nPEP) to HIV

| Recommendations for nPEP with a substantial risk for HIV exposure is a 28-day course of the preferred regimen of HAART*† | |

| NNRTI-based | Efavirenz plus either lamivudine or emtricitabine plus either zidovudine or tenofovir |

| or | |

| PI-based | Lopinavir/ritonavir plus either lamivudine or emtricitabine plus zidovudine |

| A substantial risk is exposure of any of these: | |

HAART, Highly active antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

* Either when a substantial risk has occurred and more than 72 hours has passed since the exposure or when the exposure is considered to be a negligible risk, nPEP is not recommended.

† When a substantial risk has occurred and less than 72 hours has passed since the exposure but the HIV-infection status of the source person is not known, nPEP is determined on a case-by-case basis.

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 54(RR-2), 1-27.

Transmission and Health Care Workers

Needle stick or “sharps” injuries are the main means of occupation-related HIV infection for health care workers. In addition, health care workers can be infected through exposure of nonintact skin and mucous membranes to blood and body fluids. Because of the time lag between the time of infection with HIV and the production of serum antibodies (seroconversion), infected people can test negative for HIV and still transmit the virus. The best prevention for health care providers is the consistent use of Standard Precautions for all patients as recommended by the CDC and required by The Joint Commission (TJC) (see Chapter 25). Chart 21-3 lists the recommended actions for prevention of HIV infection after a needle stick or other occupational exposure (postexposure prophylaxis [PEP]). When the source patient is known to be HIV negative, PEP is not recommended.

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Updated Public Health Service guidelines for the management of health-care worker exposure to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 54(RR-9), 1-22.

Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care: Postexposure Prophylaxis (PEP) for Occupational HIV Exposure*

| BASIC PEP† | EXPANDED PEP‡ |

|---|---|

* When PEP therapy is instituted, the recommended course is 28 days.

† Basic PEP = Two drugs: (zidovudine plus lamivudine or emtricitabine); or (stavudine plus lamivudine or emtricitabine); or (tenofovir plus lamivudine or emtricitabine).

‡ Expanded PEP = Three or more drugs: (zidovudine plus lamivudine or emtricitabine plus lopinavir/ritonavir); or (stavudine plus lamivudine or emtricitabine plus lopinavir/ritonavir); or (tenofovir plus lamivudine or emtricitabine plus lopinavir/ritonavir).

The public may be concerned about HIV transmission by health care workers. Health care workers should wear gloves when in contact with patients’ mucous membranes or nonintact skin. Infected workers with weeping dermatitis or open lesions should not perform direct care. The CDC guidelines for preventing HIV transmission by health care workers during exposure-prone invasive procedures are listed in Chart 21-4. These include any procedure in which there is a risk for broken skin injury to the health care worker and the worker’s blood is likely to make contact with the patient’s body cavity, subcutaneous tissues, or mucous membranes. The purpose of these guidelines is to reduce the risk for HIV transmission to patients.

Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Recommendations for Preventing HIV Transmission by Health Care Workers

• Workers should adhere to Standard Precautions.

• Workers with exudative lesions or weeping dermatitis should not perform direct patient care or handle patient care equipment and devices used in invasive procedures.

• Workers must follow guidelines for disinfection and sterilization of reusable equipment used in invasive procedures.

• Workers infected with HIV are not restricted from practice of non–exposure-prone procedures, as long as they comply with Standard Precautions and sterilization and disinfection recommendations.

• Workers should identify exposure-prone procedures by institutions where they are performed.

• Workers who perform exposure-prone procedures should know their HIV antibody status.

• Workers who are infected with HIV should seek advice from an expert review panel before performing exposure-prone procedures to determine under what circumstances they may continue to practice these procedures. These circumstances would include notification of prospective patients of HIV positivity.

Modified from Centers for Disease Control. (1991). Recommendations for preventing transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus to patients during exposure-prone invasive procedures. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 40(RR-8), 1-9.

Teamwork and Collaboration; Safety

Testing

Testing for HIV antibodies or other features of the virus is complex, requiring interpretation, counseling, and confidentiality. Testing plays a role in prevention because tests are a way of diagnosing HIV infection before immune changes or symptoms develop. A primary health care focus for testing is to teach those who test positive to modify their behaviors to prevent transmission to others. Therefore all sexually active people should know their HIV status. Chart 21-5 lists additional conditions for which HIV antibody testing is advised.

Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: CDC Recommendations for HIV Testing

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Modified from Centers for Disease Control. (1987). Public Health Service guidelines for counseling and antibody testing to prevent HIV infection and AIDS. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 36(31), 509-515.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

HIV disease and AIDS are a progression continuum. The patient with HIV disease may either have few manifestations and problems or may have problems that are acute rather than chronically present. As the disease progresses, however, more health problems of long duration and greater severity occur. He or she may not realize that the disease is progressing. Assess for manifestations that cluster as symptoms of disease progression and may indicate that the treatment regimen needs to be modified (Chart 21-6).