Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Gynecologic Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

7 Compare the pathophysiology, manifestations, and treatments of common menstrual cycle disorders.

9 Develop a teaching plan for a patient with a vaginal inflammation or infection.

10 Discuss common assessment findings associated with menopause.

11 Prioritize care after surgery for the woman undergoing an anterior and/or posterior repair.

12 Develop a plan of care for a patient undergoing a hysterectomy.

13 Explain the purpose of radiation and chemotherapy for patients with gynecologic cancers.

14 Provide information about complementary and alternative therapies.

15 Develop a community-based plan of care for patients with gynecologic cancers.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for the NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The most common gynecologic manifestations are pain, vaginal discharge, and bleeding. Some patients also have urinary symptoms associated with their gynecologic problem. Women are often hesitant to seek medical attention for these problems because of fear of a life-threatening disease diagnosis or concern about privacy and dignity. Be sensitive to the woman’s concerns and encourage discussion about menstrual or other reproductive problems. Teach women about their bodies, and help them recognize when professional help should be sought. Teach them how to make informed decisions about treatments. Assess the effects of gynecologic disorders on sexuality in any setting. These health problems often impair sexual function and therefore can affect the woman’s relationship with her partner. Remember that sexuality affects a woman’s sense of being, self-esteem, and body image.

Endometriosis

Pathophysiology

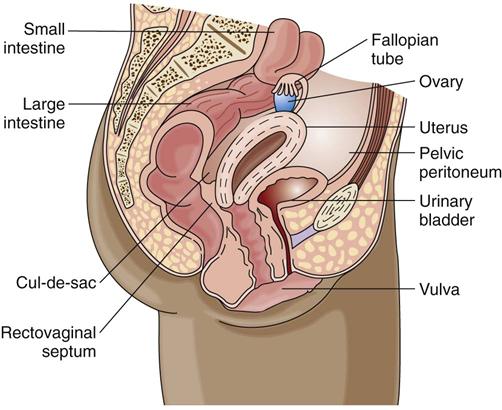

Endometriosis is endometrial (inner uterine) tissue implantation outside the uterine cavity. The tissue typically appears on the ovaries and the cul-de-sac (posterior rectovaginal wall) and less commonly on other pelvic organs and structures (Fig. 74-1). A “chocolate” cyst is an area of endometriosis on an ovary. The disease affects millions of women in the United States and Canada.

Endometriosis responds to cyclic hormonal stimulation just as if it were in the uterus. Monthly cyclic bleeding occurs at the ectopic (out of place) site of implantation, which irritates and scars the surrounding tissue. Scarring can lead to adhesions, causing infertility (inability to become pregnant). Endometriosis progresses slowly and regresses during pregnancy and at menopause. Rarely does it become cancerous.

The cause of endometriosis is unknown. One theory is that the endometrial tissue migrates directly through the fallopian tubes during menses. The tissue then implants on pelvic structures or distant organs such as lungs or heart. The formation theory suggests that endometrial tissue develops outside the uterus as a birth defect. Other theories focus on immune, genetic, and environmental factors (e.g., exposure to dioxin, a toxic chemical). Many women with endometriosis have allergies and chemical sensitivities.

The disorder is most often found in women during their reproductive years, but it can affect women into their 80s. The prevalence among infertile women is higher than it is for women who are fertile. It is also common in those whose mothers had endometriosis.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Collect a detailed history, including the woman’s menstrual history, sexual history, and bleeding characteristics. Pain is the most common symptom of endometriosis. The pain usually peaks just before the menstrual flow. It is usually located in the lower abdomen, causing many women to feel a sense of rectal pressure. The degree of pain is not related to the extent of the endometriosis but to the site. Often, women with minimal disease have more severe pain than do women with extensive disease. Other manifestations include dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), painful defecation, low backache, and infertility. GI disturbances such as nausea and diarrhea are also common. Always ask about current or past physical or sexual abuse.

A pelvic examination may reveal pelvic tenderness, tender nodules in the posterior vagina, and limited movement of the uterus. Psychosocial assessment may reveal anxiety because of uncertainty about the diagnosis. The woman may also have concerns about her self-concept if she is infertile but wants to become pregnant.

Diagnostic studies include tests to rule out pelvic inflammatory disease caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. Serum cancer antigen CA-125 helps screen for ovarian cancer but also may be positive in women with endometriosis. Transvaginal ultrasound is used to differentiate pelvic masses that might be mistaken for endometriosis.

Interventions

Hormonal and surgical management may be used, depending on the symptoms, the extent of disease, and the woman’s desire for childbearing. Collaborative care is aimed at:

Nonsurgical Management

Several resources, such as the Endometriosis Association (www.endometriosisassn.org) and RESOLVE (an organization for infertile couples) (www.resolve.org), offer information on endometriosis that is helpful for patients and caregivers.

Disease management depends of the patient’s symptoms, severity, and preference for treatment. Menstrual cycle control using oral contraceptives or progestins, such as oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera, Medroxyhexal, Alti-MPA ![]() Novo-Medrone

Novo-Medrone ![]() ) and norethindrone acetate (Aygestin, Norlutate

) and norethindrone acetate (Aygestin, Norlutate ![]() ), may be prescribed. Injectable forms of progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera), may be more convenient because these drugs are taken every 2 weeks or monthly.

), may be prescribed. Injectable forms of progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera), may be more convenient because these drugs are taken every 2 weeks or monthly.

Continuous low-level heat using wearable heat packs may provide temporary pain relief. Relaxation techniques, yoga, massage, and biofeedback may decrease muscle tissue hypoxia and hypertonicity and relieve ischemia by increasing blood flow to the affected areas. Calcium and magnesium may also relieve muscle cramping for some patients.

Surgical Management

Surgical management of endometriosis for a woman who wants to remain fertile is the laparoscopic removal of endometrial implants and adhesions in a same-day surgical setting. Chapter 18 describes the general postoperative care for patients having surgery. The surgeon may use a laser to treat endometriosis by vaporizing adhesions and endometrial implants. Teach patients that temporary postoperative pain from carbon dioxide can occur in the shoulders and chest.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Pathophysiology

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) is excessive and frequent bleeding (more than every 21 days). It is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after ruling out anatomic or systemic conditions such as drug therapy or disease. DUB occurs most often at the beginning or end of a woman’s reproductive years—when ovulation is becoming established or when it is becoming irregular at or after menopause.

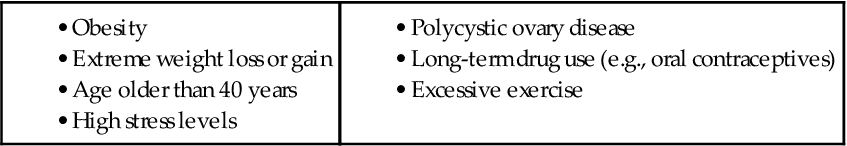

Normally the menstrual cycle is a series of delicately timed hormonal events regulated by hypothalamic, pituitary, ovarian, and uterine functions. Menses, the sloughing of the endometrial lining, is an expected result. DUB occurs when there is a hormonal imbalance. Generally, it happens when the ovaries fail to ovulate. This decreases progesterone production, which is needed to mature the uterine lining and prevent overgrowth. Without progesterone, prolonged estrogen stimulation causes the endometrium to grow past its hormonal support, causing disordered shedding of uterine lining. Most cases of DUB are classified into two types: anovulatory DUB (most common) and ovulatory DUB (Ayers & Montgomery, 2009). Common risk factors for DUB during the reproductive years are listed in Table 74-1.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

When interviewing a woman with DUB, take a complete menstrual history. Ask about illnesses, changes in weight or nutritional intake, exercise, drug ingestion, and whether she has pain.

Assess for symptoms of anemia or systemic disease, such as:

The health care provider inspects the external genitalia and does a bimanual pelvic examination, Papanicolaou test, and rectal examination to identify infections, lesions, or tenderness. Vaginal specimens are also tested for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as that caused by chlamydia. Women at high risk for endometrial cancer should also have an endometrial biopsy. Risk factors are described later in this chapter.

A complete blood count determines if the patient is anemic. Depending on the patient’s history and physical examination, thyroid-stimulating hormone and reproductive hormone levels may be evaluated.

Transvaginal ultrasound may reveal leiomyomas (fibroids) and measure an excessively thick endometrium. Sonohysterography uses vaginal ultrasound to visualize the uterus after 5 to 10 mL of sterile saline is infused through the cervix, thus outlining the inner uterine cavity.

Interventions

Management of the patient often includes nonsurgical and surgical interventions. When nonsurgical treatment is not effective, surgery may be performed.

Nonsurgical Management

As with endometriosis, hormone manipulation is usually the treatment of choice for women with anovulatory DUB. The drugs used depend on the severity of bleeding and age of the patient. Progestin or combination hormone therapy (estrogen and progestin) is indicated when bleeding is heavy and acute. For nonemergent bleeding, contraceptives (oral or patch) provide the progestin (artificial progesterone) needed to stabilize the endometrial lining. Progestin-only pills (e.g., norethindrone [Aygestin, Norlutate ![]() ]) or long-acting progestins (e.g., injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo-Provera]) are preferable for women older than 35 years who smoke or are at risk for thrombophlebitis. Some cases are managed with injectable leuprolide (Lupron), a gonadotropin-releasing (GR) hormone analog, to reduce the follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormone levels to cause amenorrhea. This drug has many potent side and adverse effects and is not used as frequently today.

]) or long-acting progestins (e.g., injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo-Provera]) are preferable for women older than 35 years who smoke or are at risk for thrombophlebitis. Some cases are managed with injectable leuprolide (Lupron), a gonadotropin-releasing (GR) hormone analog, to reduce the follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormone levels to cause amenorrhea. This drug has many potent side and adverse effects and is not used as frequently today.

Explain the desired effects and the side effects of these drugs, and evaluate the woman’s knowledge of the effects, dosage, and schedule. Be sure to remind her to take the drug exactly as prescribed and to not skip a dose or run out of it. If bleeding worsens, teach the patient to call her health care provider immediately.

Surgical Management

Removal of the built-up uterine lining, called endometrial ablation, stops the blood flow to fibroids that are causing excessive bleeding. This is a safe alternative for women who do not respond to medical management. Other invasive options include uterine artery embolization, dilation and curettage, and hysterectomy. A hysterectomy is performed only after other treatments have failed. (Hysterectomy is discussed under Surgical Management on p. 1619 of the Uterine Leiomyoma section.)

Vulvovaginitis

Pathophysiology

Vaginal discharge and itching are two problems experienced by most women at some time in their lives. Women can suffer vaginal infections from both sexually and non–sexually transmitted sources. Gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus are sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) discussed in Chapter 76.

Vulvovaginitis is inflammation of the lower genital tract resulting from a disturbance of the balance of hormones and flora in the vagina and vulva. It may be characterized by itching, change in vaginal discharge, odor, or lesions. The most common causes include:

• Fungal (yeast) infections (Candida albicans)

• STDs (Trichomonas vaginalis)

• Postmenopausal vaginal atrophy

• Changes in the normal flora or pH (from douching)

• Chemical irritant or allergens (vaginal spray, fabric dyes, detergent) or foreign body (tampon)

• Drugs, especially antibiotics

• Immunosuppression from diabetes or human immune deficiency virus (HIV)

Primary infections that affect the vulva include herpes genitalis and condylomata acuminata (human papilloma virus, venereal warts) (see Chapter 76). Secondary infections of the vulva are caused by organisms responsible for the many types of vaginitis, including candidiasis. Pediculosis pubis (crab lice) and scabies (itch mite) are common parasitic infestations of the skin of the vulva. Other causes of vulvitis include:

• Lichen planus (thickened, leathery skin from scratching)

• Vulvar leukoplakia (postmenopausal atrophy and thickening of vulvar tissues)

Some women may have an itch-scratch-itch cycle, in which the itching leads to scratching, which causes excoriation that then must heal. As healing takes place, itching occurs again. If the cycle is not interrupted, the chronic scratching may lead to the white, thickened skin of lichen planus. This dry, leathery skin cracks easily, increasing the woman’s risk for infection.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assess for vulvovaginitis by asking questions about the symptoms, assisting with a pelvic examination, and obtaining vaginal smears for laboratory testing. Inquire about symptoms of itching and burning sensation. Erythema (redness), edema, and superficial skin ulcers also may be present. Use a nonjudgmental approach and provide reassurance during the assessment because the patient may be embarrassed or afraid to discuss her symptoms. Encourage her to talk about her problem and its effect on her sexual health.

Interventions for vulvovaginitis depend on the causes and the specific vaginal infection. Proper health habits can benefit treatment. Instruct the patient to get enough rest and sleep, observe good dietary habits, exercise regularly, and use good personal hygiene. Teach her about how to manage her infection (Chart 74-1). Chart 74-2 outlines measures to help prevent further infections.

Nursing interventions to relieve itching include applying wet compresses, sitz baths for 30 minutes several times a day, and using topical drugs such as estrogens and lidocaine. Encourage the removal of any irritant or allergen, such as changing detergents.

Treatment of pediculosis and scabies is used if needed and includes:

• Applying lindane (Kwell, Kwellada ![]() ) lotion, shampoo, or cream to the affected area as directed

) lotion, shampoo, or cream to the affected area as directed

• Cleaning affected clothes, bedding, and towels

• Disinfecting the home environment (lice cannot live for more than 24 hours away from the body)

Toxic Shock Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) was first recognized in 1980 when it was found to be related to menstruation and tampon use. Other conditions associated with TSS include surgical wound infection, nonsurgical infections, and gynecologic surgeries. Use of internal contraceptives has also been linked to this health problem.

In infection related to menstruation, menstrual blood provides a growth medium for Staphylococcus aureus (or, less frequently, Streptococcus). Exotoxins produced from the bacteria cross the vaginal mucosa to the bloodstream via microabrasions from tampon insertion or prolonged use. A small number of TSS cases are fatal. Extensive public education has led to a decreased number of women having the infection.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Within 24 hours of contact with the causative agent, the abrupt onset of a high fever, along with headache, flu-like symptoms, and severe hypotension with fainting, is often present. A sunburn-like rash with broken capillaries in the eyes and skin is another warning sign of TSS. Because not all women have all these manifestations, the criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are used to verify cases (Chart 74-3). Educate all women on the prevention of TSS (Chart 74-4).

Treatment includes removal of the infection source, such as a tampon; restoring fluid and electrolyte balance; drugs to manage hypotension; and IV antibiotics. Other measures may include transfusions to reverse low platelet counts and corticosteroids to treat skin changes.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pathophysiology

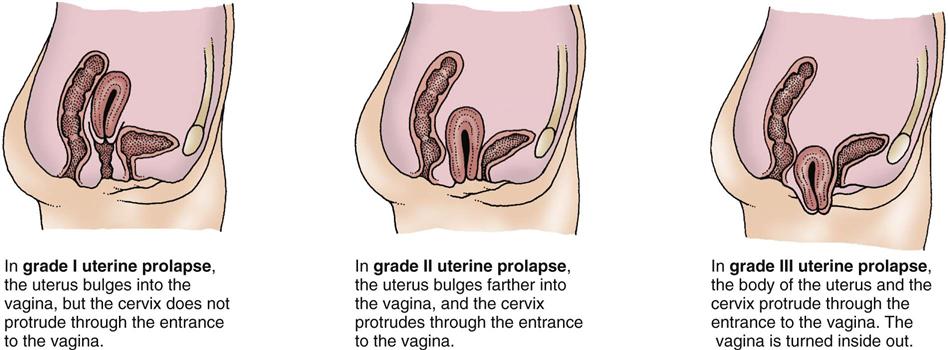

The pelvic organs are supported by a sling of muscles and tendons, which sometimes become weak and no longer able to hold an organ in place. Uterine prolapse, the most common type of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be caused by neuromuscular damage of childbirth; increased intra-abdominal pressure related to pregnancy, obesity, or physical exertion; or weakening of pelvic support due to decreased estrogen. The stages of uterine prolapse are described by the degree of descent of the uterus (Fig. 74-2) through the pelvic floor.

Whenever the uterus is displaced, other structures such as the bladder, rectum, and small intestine can protrude through the vaginal walls (Fig. 74-3). A cystocele is a protrusion of the bladder through the vaginal wall (urinary bladder prolapse), which can lead to stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urinary tract infections (UTIs). A rectocele is a protrusion of the rectum through a weakened vaginal wall (rectal prolapse).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Assessment findings for patients with a suspected uterine prolapse include the patient’s feeling as if “something is falling out,” dyspareunia (painful intercourse), backache, and a feeling of heaviness or pressure in the pelvis. A pelvic examination may reveal a protrusion of the cervix when the woman is asked to bear down. Listen to her concerns, and note signs of depression from having long-term symptoms.

Ask the patient about manifestations that may indicate that she has a cystocele. These signs and symptoms may include:

A pelvic examination reveals a large bulge of the anterior vaginal wall when the woman is asked to bear down. Diagnostic tests include cystography (to show the presence of bladder herniation), measurement of residual urine by bladder ultrasound, and urine culture and sensitivity testing. Radiographic imaging of urinary anatomy and voiding function is useful in determining the degree of cystocele.

Rectocele assessment usually includes symptoms of constipation, hemorrhoids, fecal impaction, and feelings of rectal or vaginal fullness. A vaginal and rectal examination may show a bulge of the posterior vaginal wall when the woman is asked to bear down.

Interventions

Interventions are based on the degree of the POP. Conservative treatment is preferred over surgical treatment when possible.

Nonsurgical Management

Teach women to improve pelvic support and tone via pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs, or Kegel exercises). Space-filling devices such as pessaries or spheres can be worn in the vagina to elevate the uterine prolapse. Intravaginal estrogen therapy may be prescribed for the postmenopausal woman to prevent atrophy and weakening of vaginal walls. Women with bladder symptoms may benefit from bladder training and attention to complete emptying. Management of a rectocele focuses on promoting bowel elimination. The health care provider usually prescribes a high-fiber diet, stool softeners, and laxatives.

Surgical Management

Surgery may be recommended for severe symptoms. Address the fears and concerns of the patient and her family. The least invasive procedure is usually used.

Transvaginal repair for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) using surgical vaginal mesh or tape is a commonly performed minimally invasive technique. It is particularly useful for women who are very obese. Depending on the procedure that is planned, the patient has either local or general anesthesia. The surgeon creates a sling with the mesh or tape, and the woman is discharged the same day. Procedures done under local anesthesia can be done in the surgeon’s office. Over the past several years, patient report of several rare complications associated with the use of transvaginal mesh has required the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to recall at least one company’s product. These complications include vaginal erosion and severe infection (Mirsaidi, 2009).

Patients who choose to have the procedure may return to usual activities, including driving, 2 weeks after surgery. Teach them to avoid sexual intercourse for at least 6 weeks or as the surgeon recommends.

Alternatives to minimally invasive surgery are open surgical techniques. An anterior colporrhaphy (anterior repair) tightens the pelvic muscles for better bladder support. A vaginal surgical approach is used and may be done as a laparoscopic-assisted procedure. Nursing care for a woman undergoing an anterior repair is similar to that for a woman undergoing a vaginal hysterectomy.

After surgery, instruct the patient to limit her activities. Teach her to avoid lifting anything heavier than 5 pounds, strenuous exercises, and sexual intercourse for 6 weeks. For discomfort, tell her to use heat either as a moist heating pad or warm compresses applied to the abdomen. A hot bath may also be helpful. Sutures do not need to be removed because some are absorbable and others will fall out as healing occurs. Tell the woman to notify her health care provider if she has signs of infection, such as fever, persistent pain, or purulent, foul-smelling discharge. Encourage her to keep her follow-up appointment after surgery.

Posterior colporrhaphy (posterior repair) reduces rectal bulging. If both a cystocele and a rectocele are present, an anterior and posterior colporrhaphy (A&P repair) is performed.

The nursing care after a posterior repair is similar to that after any rectal surgery. After surgery, a low-residue (low-fiber) diet is usually prescribed to decrease bowel movements and allow time for the incision to heal. Instruct the patient to avoid straining when she does have a bowel movement so that she does not put pressure on the suture line. Bowel movements are often painful, and she may need pain medication before having a stool. Provide sitz baths or delegate this activity to unlicensed nursing personnel to relieve the woman’s discomfort. Health teaching for the patient undergoing a posterior repair is similar to that for the patient undergoing an anterior repair.

Vaginal hysterectomy may accompany any uterine prolapse repair surgery unless the woman wants children or more children. This procedure is described on p. 1619.

Benign Neoplasms

Ovarian Cyst

Functional ovarian cysts can occur in a woman of any age but are rare after menopause. Other cysts and tumors of the ovaries are not related to the menstrual cycle but arise from ovarian tissue. Primary assessment involves pelvic examination and transvaginal ultrasound. Further testing with computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or laparoscopic biopsy to rule out cancer may be indicated. Some ovarian cysts disappear over time, and others cause discomfort for a prolonged period. Laparoscopic surgery to remove the cyst or ovary may be needed.

Uterine Leiomyoma

Pathophysiology

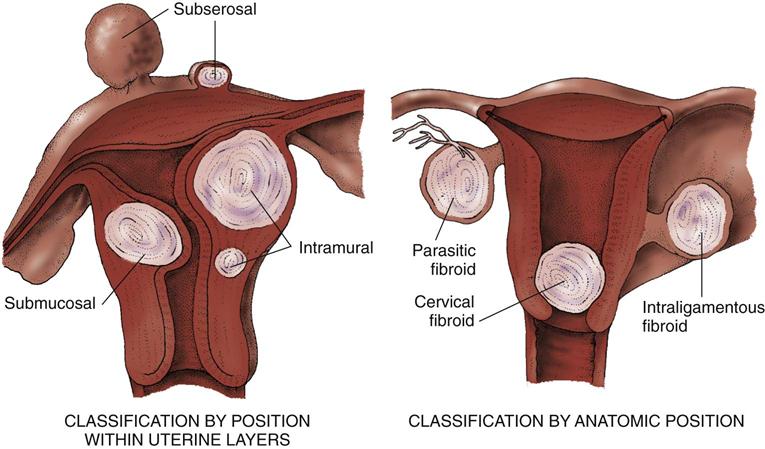

Leiomyomas, also called fibroids or myomas, are benign, slow-growing solid tumors of the uterine myometrium (muscle layer). They are classified according to their position in the layers of the uterus. The most common types are intramural, submucosal, and subserosal (Fig. 74-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree