Chapter 74 Care of Patients with Gynecologic Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Collaborate with members of the health care team when caring for patients with gynecologic cancers.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Identify the risk factors for gynecologic cancers.

3. Provide health teaching on community resources for patients with gynecologic health problems.

4. Describe evidence-based health promotion and maintenance measures to help prevent or early-detect gynecologic cancers.

5. Explain the psychosocial needs of patients with gynecologic health problems, including their effect on sexuality.

6. Discuss ways to help patients adapt to physical changes, including impaired sexuality, caused by gynecologic problems and their treatment.

7. Compare the pathophysiology, manifestations, and treatments of common menstrual cycle disorders.

8. Describe the mechanisms of action, side effects, and nursing implications of drug therapy for endometriosis.

9. Develop a teaching plan for a patient with a vaginal inflammation or infection.

10. Discuss common assessment findings associated with menopause.

11. Prioritize care after surgery for the woman undergoing an anterior and/or posterior repair.

12. Develop a plan of care for a patient undergoing a hysterectomy.

13. Explain the purpose of radiation and chemotherapy for patients with gynecologic cancers.

14. Provide information about complementary and alternative therapies.

15. Develop a community-based plan of care for patients with gynecologic cancers.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for the NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Endometriosis

Pathophysiology

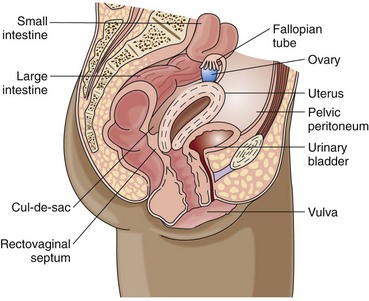

Endometriosis is endometrial (inner uterine) tissue implantation outside the uterine cavity. The tissue typically appears on the ovaries and the cul-de-sac (posterior rectovaginal wall) and less commonly on other pelvic organs and structures (Fig. 74-1). A “chocolate” cyst is an area of endometriosis on an ovary. The disease affects millions of women in the United States and Canada.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

Several resources, such as the Endometriosis Association (www.endometriosisassn.org) and RESOLVE (an organization for infertile couples) (www.resolve.org), offer information on endometriosis that is helpful for patients and caregivers.

Surgical Management

Surgical management of endometriosis for a woman who wants to remain fertile is the laparoscopic removal of endometrial implants and adhesions in a same-day surgical setting. Chapter 18 describes the general postoperative care for patients having surgery. The surgeon may use a laser to treat endometriosis by vaporizing adhesions and endometrial implants. Teach patients that temporary postoperative pain from carbon dioxide can occur in the shoulders and chest.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Pathophysiology

Normally the menstrual cycle is a series of delicately timed hormonal events regulated by hypothalamic, pituitary, ovarian, and uterine functions. Menses, the sloughing of the endometrial lining, is an expected result. DUB occurs when there is a hormonal imbalance. Generally, it happens when the ovaries fail to ovulate. This decreases progesterone production, which is needed to mature the uterine lining and prevent overgrowth. Without progesterone, prolonged estrogen stimulation causes the endometrium to grow past its hormonal support, causing disordered shedding of uterine lining. Most cases of DUB are classified into two types: anovulatory DUB (most common) and ovulatory DUB (Ayers & Montgomery, 2009). Common risk factors for DUB during the reproductive years are listed in Table 74-1.

TABLE 74-1 RISK FACTORS FOR DYSFUNCTIONAL UTERINE BLEEDING

Vulvovaginitis

Pathophysiology

Vaginal discharge and itching are two problems experienced by most women at some time in their lives. Women can suffer vaginal infections from both sexually and non–sexually transmitted sources. Gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus are sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) discussed in Chapter 76.

• Fungal (yeast) infections (Candida albicans)

• STDs (Trichomonas vaginalis)

• Postmenopausal vaginal atrophy

• Changes in the normal flora or pH (from douching)

• Chemical irritant or allergens (vaginal spray, fabric dyes, detergent) or foreign body (tampon)

• Drugs, especially antibiotics

• Immunosuppression from diabetes or human immune deficiency virus (HIV)

Primary infections that affect the vulva include herpes genitalis and condylomata acuminata (human papilloma virus, venereal warts) (see Chapter 76). Secondary infections of the vulva are caused by organisms responsible for the many types of vaginitis, including candidiasis. Pediculosis pubis (crab lice) and scabies (itch mite) are common parasitic infestations of the skin of the vulva. Other causes of vulvitis include:

• Lichen planus (thickened, leathery skin from scratching)

• Vulvar leukoplakia (postmenopausal atrophy and thickening of vulvar tissues)

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Interventions for vulvovaginitis depend on the causes and the specific vaginal infection. Proper health habits can benefit treatment. Instruct the patient to get enough rest and sleep, observe good dietary habits, exercise regularly, and use good personal hygiene. Teach her about how to manage her infection (Chart 74-1). Chart 74-2 outlines measures to help prevent further infections.

Chart 74-1 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Vaginal Infections

• Your risk for getting vaginal infections increases if you have sex with more than one person.

• When you have a vaginal infection, do not have sexual intercourse, if possible, or at least make sure that your partner wears a condom.

• Sexual partners may need to be treated for infection.

• The only way to identify what infection you have is to be examined by a health care provider and to get the results of laboratory tests.

• Take your medicine as prescribed, not just until your symptoms go away.

Chart 74-2 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Prevention of Vulvovaginitis

• Avoid wearing tight clothing, such as pantyhose or tight jeans, because they can cause chafing. You can also get hot and sweaty, which can cause an infection.

• Always wipe front to back after having a bowel movement or urinating.

• During bath or shower, cleanse inner labial mucosa with water, not soap.

• Do not douche or use feminine hygiene sprays.

• If your sexual partner has an infection of the sex organs, do not have intercourse with him or her until he or she has been treated.

• You are more likely to get an infection if you are pregnant, have diabetes, take oral contraceptive drugs, or are menopausal.

Treatment of pediculosis and scabies is used if needed and includes:

• Applying lindane (Kwell, Kwellada ![]() ) lotion, shampoo, or cream to the affected area as directed

) lotion, shampoo, or cream to the affected area as directed

• Cleaning affected clothes, bedding, and towels

• Disinfecting the home environment (lice cannot live for more than 24 hours away from the body)

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Toxic Shock Syndrome

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Within 24 hours of contact with the causative agent, the abrupt onset of a high fever, along with headache, flu-like symptoms, and severe hypotension with fainting, is often present. A sunburn-like rash with broken capillaries in the eyes and skin is another warning sign of TSS. Because not all women have all these manifestations, the criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are used to verify cases (Chart 74-3). Educate all women on the prevention of TSS (Chart 74-4).

Toxic Shock Syndrome

• Fever (temperature >102° F [38.9° C])

• Diffuse rash resembling sunburn

• Peeling of skin—primarily the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands—1 to 2 wk after onset of the illness

• Hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or orthostatic syncope)

• Involvement of three or more of these:

• Negative results for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, measles, and scarlet fever and for throat, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures

• Positive culture for Staphylococcus aureus from blood, urine, or stool

Chart 74-4 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Prevention of Toxic Shock Syndrome

• Wash your hands before inserting a tampon.

• Do not use a tampon if it is dirty.

• Insert the tampon carefully to avoid injuring the delicate tissue in your vagina.

• Change your tampon every 3 to 6 hours.

• Do not use superabsorbent tampons.

• Use sanitary napkins at night.

• Call your health care provider if you suddenly experience a high temperature, vomiting, or diarrhea.

• Do not use tampons at all if you have had toxic shock syndrome.

• Not using tampons almost guarantees that you will not get toxic shock syndrome.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pathophysiology

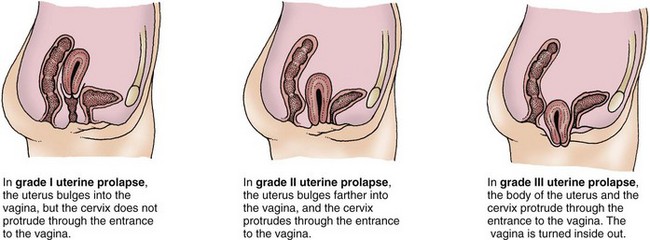

The pelvic organs are supported by a sling of muscles and tendons, which sometimes become weak and no longer able to hold an organ in place. Uterine prolapse, the most common type of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be caused by neuromuscular damage of childbirth; increased intra-abdominal pressure related to pregnancy, obesity, or physical exertion; or weakening of pelvic support due to decreased estrogen. The stages of uterine prolapse are described by the degree of descent of the uterus (Fig. 74-2) through the pelvic floor.

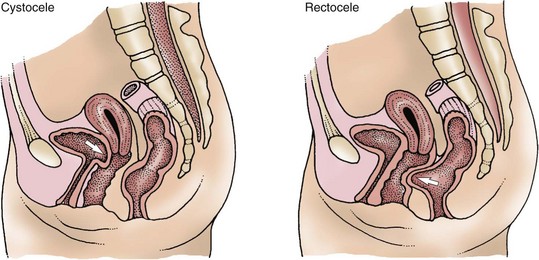

Whenever the uterus is displaced, other structures such as the bladder, rectum, and small intestine can protrude through the vaginal walls (Fig. 74-3). A cystocele is a protrusion of the bladder through the vaginal wall (urinary bladder prolapse), which can lead to stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urinary tract infections (UTIs). A rectocele is a protrusion of the rectum through a weakened vaginal wall (rectal prolapse).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

• Difficulty in emptying the bladder

• Urinary frequency and urgency

• Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (loss of urine during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as laughing, coughing, sneezing, or lifting heavy objects)

Surgical Management

Transvaginal repair for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) using surgical vaginal mesh or tape is a commonly performed minimally invasive technique. It is particularly useful for women who are very obese. Depending on the procedure that is planned, the patient has either local or general anesthesia. The surgeon creates a sling with the mesh or tape, and the woman is discharged the same day. Procedures done under local anesthesia can be done in the surgeon’s office. Over the past several years, patient report of several rare complications associated with the use of transvaginal mesh has required the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to recall at least one company’s product. These complications include vaginal erosion and severe infection (Mirsaidi, 2009).

Action Alert

Benign Neoplasms

Uterine Leiomyoma

Pathophysiology

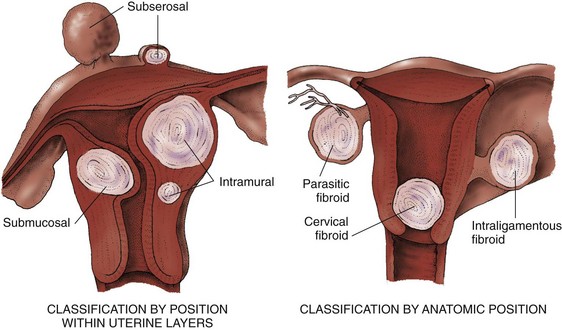

Leiomyomas, also called fibroids or myomas, are benign, slow-growing solid tumors of the uterine myometrium (muscle layer). They are classified according to their position in the layers of the uterus. The most common types are intramural, submucosal, and subserosal (Fig. 74-4).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree