Chapter 57 Care of Patients with Esophageal Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Explain the importance of collaborating with the health care team when providing care to patients with esophageal health problems that impair swallowing or limit nutrition.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Teach the patient and family about lifestyle changes to decrease gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and the discomfort of hiatal hernias.

3. Describe special considerations for the older adult with GERD.

4. Identify the need for psychosocial support to patients and their families through diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer.

5. Evaluate the impact of esophageal cancer on the patient’s nutritional status, including the risk for aspiration.

6. Perform focused assessments for patients with esophageal health problems.

7. Apply knowledge of pathophysiology to anticipate complications of GERD.

8. Plan how to teach patients with GERD about drug therapy.

9. Develop a teaching plan for the patient and family about postoperative care after esophageal surgery.

10. Apply knowledge of pathophysiology to recognize complications of esophageal surgical procedures.

11. Plan community-based care for patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Pathophysiology

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common upper GI disorder in the United States. It occurs most often in middle-aged and older adults but can affect people of any age. GERD occurs as a result of reflux (backward flow) of GI contents into the esophagus. The incidence of GERD is increasing throughout the world (Chait, 2010).

Reflux produces symptoms by exposing the esophageal mucosa to the irritating effects of gastric or duodenal contents, resulting in inflammation. A person with acute symptoms of inflammation is often described as having reflux esophagitis, which may be mild or severe (McCance et al., 2010).

The most common cause of GERD is excessive relaxation of the LES, which allows the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acidic gastric contents. Nighttime reflux tends to cause prolonged exposure of the esophagus to acid because the supine position decreases peristalsis and the benefit of gravity. Although controversial, Helicobacter pylori may contribute to reflux as well (McCance et al., 2010).

Gastric distention caused by eating very large meals or delayed gastric emptying predisposes the patient to reflux. A number of individual factors, including certain foods and drugs, influence the function of the LES (Table 57-1). Smoking and alcohol also weaken the tone of the LES.

TABLE 57-1 FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO DECREASED LOWER ESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER PRESSURE

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of reflux vary in severity, depending on the patient (Chart 57-1). Dyspepsia, also known as “heartburn,” and regurgitation are the main symptoms of GERD. The pain is described as a substernal burning sensation that tends to move up and down the chest in a wavelike fashion. Because heartburn might not be viewed as a serious concern, patients may delay seeking treatment. If the heartburn is severe, the pain may radiate to the neck or jaw or may be referred to the back. The pain typically worsens when the patient bends over, strains, or lies down. Patients may come to the emergency department (ED) fearing that they are having a myocardial infarction (“heart attack”).

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

• Whether dysphagia occurs when ingesting solids, liquids, or both

• Whether dysphagia is intermittent or occurs with each swallowing effort

Considerations For Older Adults

In the older adult, the incidence of heartburn decreases in those with gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). Instead, the more severe complications of the disease are more frequent in this population, including atypical chest pain; ear, nose, and throat infections; and pulmonary problems, such as aspiration pneumonia, sleep apnea, and asthma. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal erosions are also more common in older adults. The cause for these differences is not known (Chait, 2010).

Diagnostic Assessment

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is useful in diagnosing or evaluating reflux esophagitis or in monitoring complications such as Barrett’s esophagus. This test requires the use of moderate sedation during the procedure, and patients must have someone accompany them home after recovery. During the procedure, tissue samples can be obtained for biopsy and strictures can be dilated (see Chapter 55).

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

The purpose of treatment for GERD is to relieve symptoms, treat esophagitis, and prevent complications such as strictures or Barrett’s esophagus. For most patients, GERD can be controlled by nutrition therapy, lifestyle changes, and drug therapy. The most important role of the nurse is patient and family education. Teach the patient that GERD is a chronic disorder that requires ongoing management. The disease should be treated more aggressively in older adults (Chait, 2010).

Nonpharmacologic Interventions.

The control of GERD involves lifestyle changes to promote health and control reflux (Chart 57-2). Teach the patient to elevate the head by 6 to 12 inches for sleep to prevent nighttime reflux. This can be done by placing blocks under the head of the bed or by using a large, wedge-style pillow instead of a standard pillow.

Chart 57-2 Patient And Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Health Promotion and Lifestyle Changes to Control Reflux

• Eat four to six small meals a day.

• Limit or eliminate fatty foods, coffee, tea, cola, and chocolate.

• Reduce or eliminate from your diet any food or spice that increases gastric acid and causes pain.

• Limit or eliminate alcohol and tobacco.

• Do not snack in the evening, and take no food for 2 to 3 hours before you go to bed.

• Eat slowly and chew your food thoroughly to reduce belching.

• Remain upright for 1 to 2 hours after meals, if possible.

• Elevate the head of your bed 6 to 12 inches using wooden blocks, or elevate your head using a foam wedge. Never sleep flat in bed.

• If you are overweight, lose weight.

• Do not wear constrictive clothing.

• Avoid heavy lifting, straining, and working in a bent-over position.

• Chew “chewable” antacids thoroughly, and follow with a glass of water.

Obese patients often have obstructive sleep apnea, as well as GERD. Those who receive continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment report improved sleeping and decreased episodes of reflux at night. See Chapter 31 for a discussion of CPAP.

Drug Therapy.

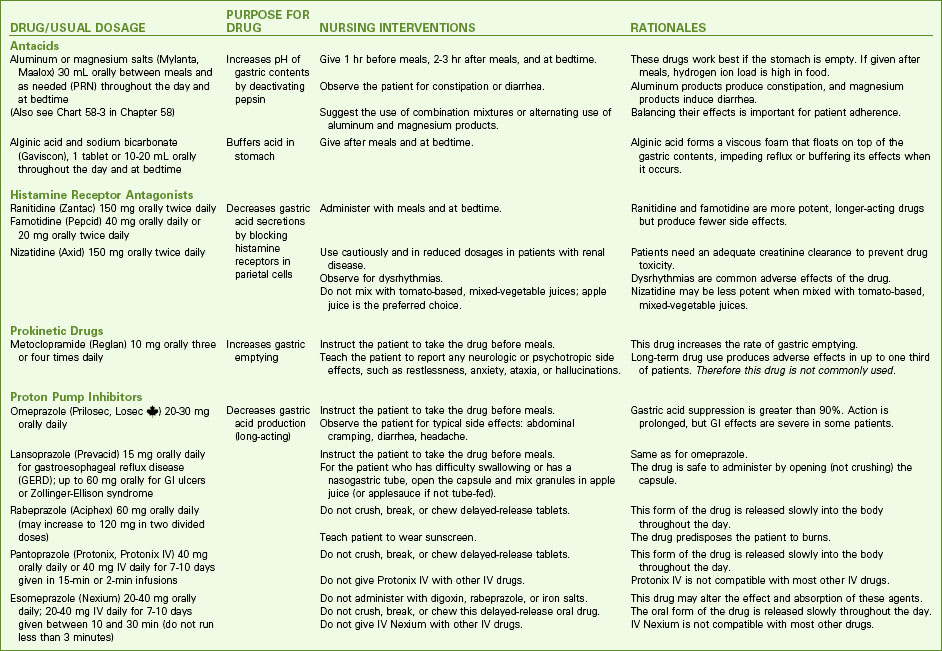

Drug therapy for GERD management includes three major types—antacids, histamine blockers, and proton pump inhibitors. These drugs have one or more of these functions (Chart 57-3):

Research has also found that long-term use of proton pump inhibitors may increase the risk for hip fracture, especially in older adults. PPIs can interfere with calcium absorption and protein digestion and therefore reduce available calcium to bone tissue. Decreased calcium makes bones more brittle and likely to fracture, especially as people age (Chait, 2010).

Physiological Integrity

Endoscopic Therapies.

In the Stretta procedure, the physician applies radiofrequency (RF) energy through the endoscope using needles placed near the gastroesophageal junction. The RF energy decreases vagus nerve activity, thus reducing discomfort for the patient. This nonsurgical procedure has also been approved for patients with Barrett’s esophagus (Bulsiewicz & Shaheen, 2011).

In the gastroplication procedure, the physician tightens the LES through the endoscope using sutures near the sphincter. Chart 57-4 outlines discharge instructions for endoscopic therapies.

Chart 57-4 Patient And Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Postoperative Instructions for Patients Having Endoscopic Therapies for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (e.g., Stretta Procedure)

• Remain on clear liquids for 24 hours after the procedure.

• After the first day, consume a soft diet, such as custard, pureed vegetables, mashed potatoes, and applesauce.

• Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin for 10 days.

• Continue drug therapy as prescribed, usually proton pump inhibitors.

• Use liquid medications whenever possible.

• Do not allow nasogastric tubes for at least 1 month because the esophagus could be perforated.

• Contact the health care provider immediately if these problems occur:

The advantages of endoscopic therapies compared with surgery include:

• Use of light or moderate sedation (rather than general anesthesia)

• Ambulatory care procedure (rather than an inpatient stay)

• Short procedure (45 minutes versus several hours)

• 1 to 2 days absence from work (rather than 2 to 3 weeks)

• No antibiotics and lower complication rate, including fewer deaths

Hiatal Hernia

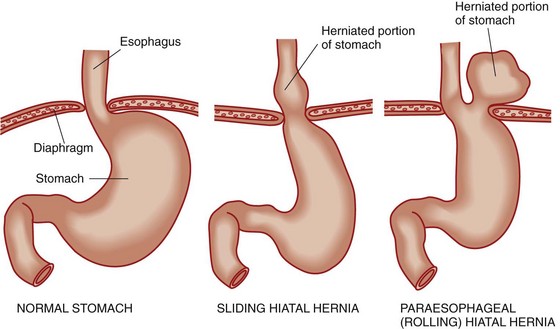

Hiatal hernias, also called diaphragmatic hernias, involve the protrusion of the stomach through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm into the chest. The esophageal hiatus is the opening in the diaphragm through which the esophagus passes from the thorax to the abdomen. Most patients with hiatal hernias are asymptomatic, but some may have daily symptoms similar to those with GERD (McCance et al., 2010).

Pathophysiology

The two major types of hiatal hernias are sliding hernias and paraesophageal (rolling) hernias. Sliding hernias are the most common type. The esophagogastric junction and a portion of the fundus of the stomach slide upward through the esophageal hiatus into the chest, usually as a result of weakening of the diaphragm (Fig. 57-1). The hernia generally moves freely and slides into and out of the chest during changes in position or intra-abdominal pressure. Although volvulus (twisting) and obstruction do occur rarely, the major concern for a sliding hernia is the development of esophageal reflux and its complications (see Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease section earlier in this chapter). The development of reflux is related to chronic exposure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to the low pressure of the thorax, which significantly reduces the effectiveness of the LES. Symptoms associated with decreased LES pressure are worsened by positions that favor reflux, such as bending or lying supine. Coughing, obesity, and ascites also increase reflux symptoms.

FIG. 57-1 A comparison of the normal stomach and sliding and paraesophageal (rolling) hiatal hernias.

With rolling hernias, also known as paraesophageal hernias, the gastroesophageal junction remains in its normal intra-abdominal location but the fundus (and possibly portions of the stomach’s greater curvature) rolls through the esophageal hiatus and into the chest beside the esophagus (see Fig. 57-1). The herniated portion of the stomach may be small or quite large. In rare cases, the stomach completely inverts into the chest. Reflux is not usually present because the LES remains anchored below the diaphragm. However, the risks for volvulus (twisting), obstruction (blockage), and strangulation (stricture) are high. The development of iron deficiency anemia is common because slow bleeding from venous obstruction causes the gastric mucosa to become engorged and ooze. Significant bleeding or hemorrhage is rare.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Ask the patient if he or she has heartburn, regurgitation (backward flow of food into the throat), pain, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and eructation (belching). Assess general physical appearance and nutritional status. Note the location, onset, duration, and quality of pain, as well as factors that relieve it or make it worse. The primary symptoms of sliding hiatal hernias are associated with reflux. Auscultate the lungs because pulmonary symptoms similar to asthma may be triggered by episodes of aspiration, particularly at night. A detailed history is crucial in attempting to differentiate angina from noncardiac chest pain caused by reflux. Symptoms resulting from hiatal hernia typically worsen after a meal or when the patient is in a supine position (Chart 57-5).

Hiatal Hernias

| Sliding Hiatal Hernias | Paraesophageal Hernias |

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|