Donna D. Ignatavicius

Care of Patients with Arthritis and Other Connective Tissue Diseases

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3 Identify community resources to help patients achieve or maintain independence in ADLs.

4 Identify risk factors for the development of arthritis and other CTDs.

5 Teach patients how to protect and exercise their joints and conserve their energy.

6 Teach patients how to prevent Lyme disease and detect it early if it occurs.

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

9 Compare and contrast the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of OA and RA.

10 Interpret laboratory findings for patients with RA and other autoimmune CTDs.

15 Evaluate and document patient response to drug therapy.

16 Differentiate between discoid lupus erythematosus and systemic lupus erythematosus.

17 Prioritize nursing interventions for patients who have systemic sclerosis.

18 Describe the patient-centered collaborative care of gout based on knowledge of pathophysiology.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Connective tissue disease (CTD) is the major focus of rheumatology, the study of rheumatic disease. A rheumatic disease is any disease or condition involving the musculoskeletal system. In this text, CTDs are discussed separately from other musculoskeletal conditions because most CTDs are classified as autoimmune disorders. In autoimmune disease, antibodies attack healthy normal cells and tissues. For reasons that are unclear, the immune system does not recognize body cells as self and therefore triggers an immune response. The usual protective nature of the immune system does not function properly in patients with autoimmune CTDs.

Most common CTDs are characterized by chronic pain and progressive joint deterioration, which results in decreased function. Some of these disorders have additional localized clinical manifestations, whereas others are systemic. The economic and social costs of these diseases are staggering and will increase steadily as “baby boomers” continue to age. Patient care usually requires an interdisciplinary approach, including medicine, surgery, nursing, rehabilitation therapy, and/or case management.

More than 46 million people in the United States have at least one of more than 100 types of CTDs, or “arthritis.” Arthritis means inflammation of one or more joints. In clinical practice, however, arthritis is categorized as either noninflammatory or inflammatory. Noninflammatory, localized arthritis such as osteoarthritis (OA) is not systemic; OA is not an autoimmune disease. Systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are inflammatory disorders.

Osteoarthritis

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis is the most common arthritis and a major cause of disability among adults in the United States and the world. It is sometimes called osteoarthrosis or degenerative joint disease (DJD).

Osteoarthritis is the progressive deterioration and loss of cartilage in one or more joints (articular cartilage). Articular cartilage, also known as hyaline cartilage, contains 65% to 80% water. The remaining components form a matrix of:

• Proteoglycans (glycoproteins containing chondroitin, keratin sulfate, and other substances)

• Collagen (elastic substance)

As people age or experience joint trauma, proteoglycans decrease. The production of synovial fluid, which provides joint lubrication and nutrition, also declines because of the decreased synthesis of hyaluronic acid and less body fluid in the older adult.

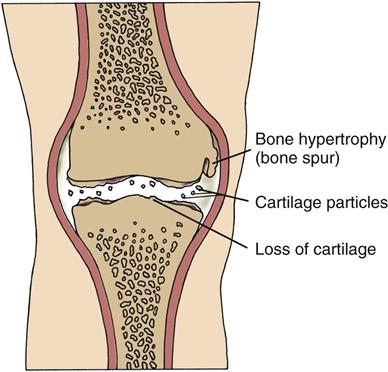

In patients of any age with OA, enzymes, such as stromelysin, break down the articular matrix. In early disease, the cartilage changes from its normal bluish white, translucent color to an opaque and yellowish brown appearance. As cartilage and the bone beneath the cartilage begin to erode, the joint space narrows and osteophytes (bone spurs) form (Fig. 20-1). As the disease progresses, fissures, calcifications, and ulcerations develop and the cartilage thins. Inflammatory cytokines (enzymes) such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) enhance this deterioration. The body’s normal repair process cannot overcome the rapid process of degeneration (McCance et al., 2010).

Eventually the cartilage disintegrates and pieces of bone and cartilage “float” in the diseased joint causing crepitus, a grating sound caused by the loosened bone and cartilage. The resulting joint pain and stiffness can lead to decreased mobility and muscle atrophy. Muscle tissue helps support joints, particularly those that bear weight (e.g., hips, knees).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

The cause of OA is a combination of many factors. For patients with primary OA, the disease may be triggered by aging, genetic changes, obesity, and/or smoking. Weight-bearing joints (hips and knees), the vertebral column, and the hands are most commonly affected, probably because they are used most often or bear the mechanical stress of body weight and many years of use.

Other factors that can lead to OA are obesity and smoking. Obesity causes joint degeneration, particularly in the knees. Smoking leads to knee cartilage loss, especially in patients with a family history of knee OA. This finding shows a gene-environment interaction in the cause of knee OA (Ding et al., 2007).

Secondary OA occurs less often than primary disease and can result from other musculoskeletal conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Trauma to the joints from excessive use or abuse also predisposes a person to OA. Certain heavy manual occupations (e.g., carpet laying, construction, farming) cause high-intensity or repetitive stress to the joints. The risk for hip and knee OA is also increased in professional athletes, especially football players, runners, and gymnasts.

In a small percentage of people, congenital anomalies, trauma, and joint sepsis can result in secondary OA. For example, injuries or joint surgeries resulting from motor vehicle crashes or falls can cause OA in later years. Certain metabolic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, Paget’s disease of the bone) and blood disorders (e.g., hemophilia, sickle cell disease) can also cause joint degeneration.

Incidence and Prevalence

The prevalence of OA varies among different populations but is a universal problem. Most people older than 60 years have joint changes that can be seen on x-ray examination, although not all of those people actually develop the disease. According to Arthritis Foundation estimates, 16 million women older than 40 years have OA compared with 11 million men. Although the cause for this difference is not known, a contributing factor is probably obesity. As women age and have children, they tend to gain more weight than men.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Based on the contributing factors for OA development, several lifestyle changes can help prevent or slow joint degeneration. These practices include:

• Stop or do not start smoking.

• Avoid or limit activities that promote stress on joints, unless absolutely necessary.

• Limit participation in recreational sports that can damage joints, such as football.

• Wear supportive shoes to prevent falls and damage to foot joints, especially metatarsal joints.

• Do not perform repetitive stress activities, such as knitting or typing, for prolonged periods.

• Avoid risk-taking activities to prevent trauma that can result in OA later in life.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Patients with OA usually seek medical attention in ambulatory care settings for their joint pain. However, you will also care for those who have OA as a secondary diagnosis in acute and chronic care facilities. Ask the patient about the course of the disease. Collect information specifically related to OA, such as the nature and location of joint pain and how much pain he or she is experiencing. Remember that older patients may underreport pain, resulting in inadequate pain management. Use a 0-to-10 scale or other assessment tool to assess pain intensity. Chapter 5 discusses pain assessment in detail.

Other questions to ask include:

• If joint stiffness has occurred, where and for how long?

• When and where has any joint swelling occurred?

• What do you do to control the pain or stiffness?

• Do you have any loss of function or difficulty in performing ADLs?

Because this disease occurs more often in older women, age and gender are important factors for the nursing history. Ask patients about their occupation, nature of work, history of trauma or falls, weight history, smoking history, and current or previous involvement in sports, because these are all risk factors for the disease. A history of obesity is significant, even for those currently within the ideal range for body weight. Document any family history of arthritis. Determine whether the patient has a current or previous medical condition that may cause joint symptoms.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

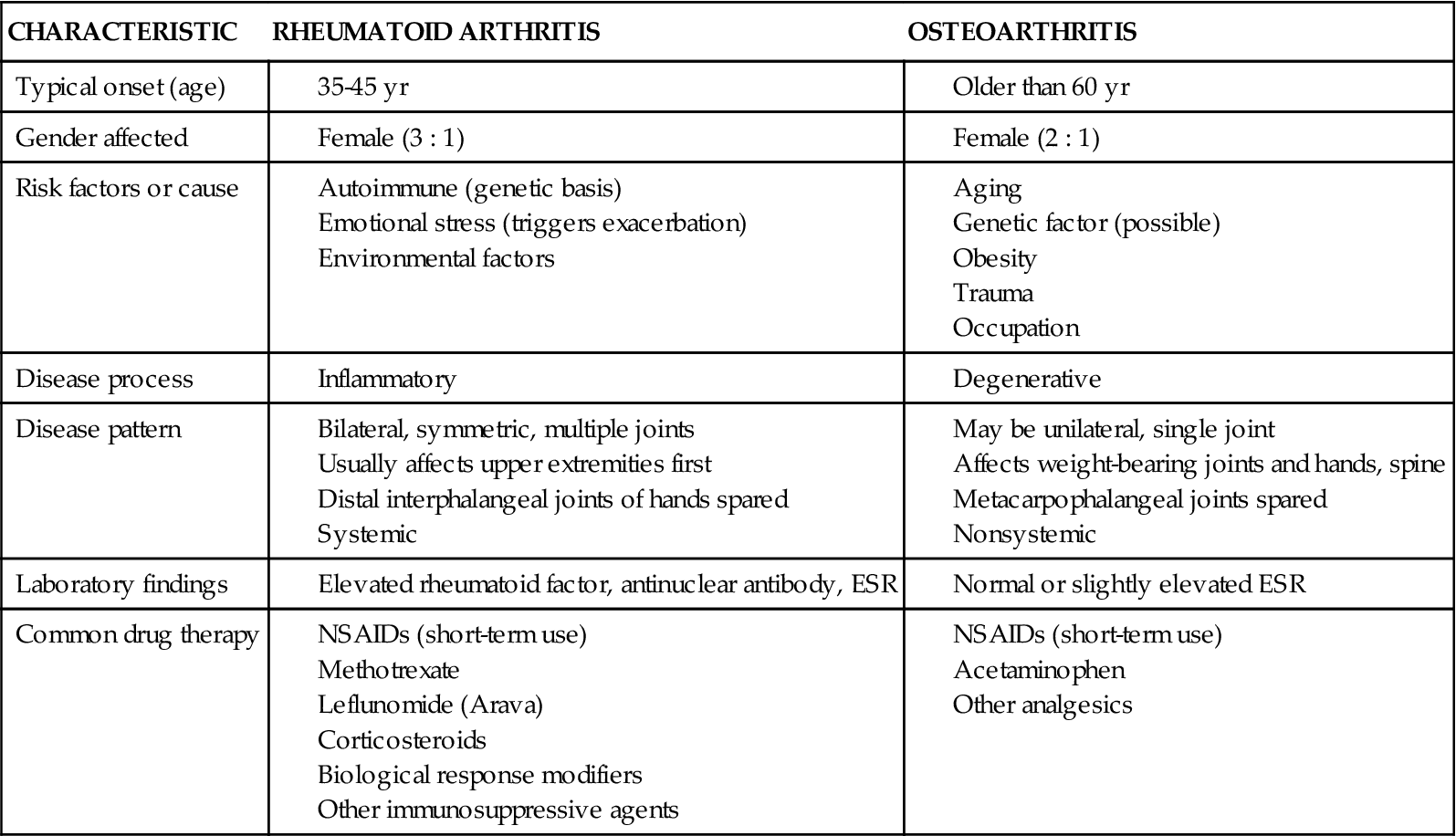

In the early stage of the disease, the clinical manifestations of OA may appear similar to those of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The distinction between OA and RA becomes more evident as the disease progresses. Table 20-1 compares the major characteristics of both diseases and their common drug therapy.

TABLE 20-1

DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS AND OSTEOARTHRITIS

| CHARACTERISTIC | RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | OSTEOARTHRITIS |

| Typical onset (age) | ||

| Gender affected | ||

| Risk factors or cause | ||

| Disease process | ||

| Disease pattern | ||

| Laboratory findings | ||

| Common drug therapy |

ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The typical patient with OA is a middle-aged or older woman who reports chronic joint pain and stiffness. Early in the course of the disease, the pain diminishes after rest and worsens after activity. Later the pain occurs with slight motion or even when at rest. Because cartilage has no nerve supply, the pain is probably caused by joint and soft-tissue involvement and by spasms of the surrounding muscles. During the joint examination, the patient may have pain or tenderness by palpation or by putting the joint through range of motion. Crepitus may be felt or heard as the joint goes through range of motion. One or more joints may be affected. The patient may also report joint stiffness that usually lasts less than 30 minutes after a period of inactivity.

On inspection, the joint is often enlarged because of bony hypertrophy. The joint feels hard on palpation. Although not common, the presence of inflammation in patients with OA indicates a secondary synovitis. About half of patients with hand involvement have Heberden’s nodes (at the distal interphalangeal [DIP] joints) and Bouchard’s nodes (at the proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joints). Although OA is not a bilateral, symmetric disease, these large bony nodes appear on both hands, especially in women. The nodes may be painful and red. Some patients experience pain in developing nodes or when nodes are palpated. These deformities tend to be familial and are often a cosmetic concern to patients.

Joint effusions (excess joint fluid) are common when the knees are involved. When trying to differentiate the presence of fluid from subcutaneous tissue, you may be able to move fluid from the infrapatellar notch (the area directly below the knee) into the suprapatellar area (directly above the knee).

Observe any atrophy of skeletal muscle from disuse. The vicious pain cycle of the disease discourages the movement of painful joints, which may result in contractures, muscle atrophy, and further pain. Loss of function may result, depending on which joints are involved. Hip or knee pain may cause the patient to limp and restrict walking distance.

Osteoarthritis (OA) can affect the spine, especially the lumbar region at the L3-4 level or the cervical region at C4-6 (neck). Compression of spinal nerve roots may occur as a result of vertebral facet bone spurs. The patient typically reports radiating pain, stiffness, and muscle spasms in one or both extremities.

Severe pain and deformity interfere with ambulation and self-care. In addition to performing a musculoskeletal assessment, collaborate with the physical and occupational therapists to conduct a functional assessment. Assess the patient’s mobility and ability to perform ADLs. Chapter 8 describes functional assessment.

Psychosocial Assessment

OA is a chronic condition that may cause permanent changes in lifestyle. An inability to care for oneself in advanced disease can result in role changes and other losses. Constant pain interferes with quality of life. Chronic pain can also affect sexuality. Patients may not have the energy for sexual intercourse or may find positioning uncomfortable (Gevirtz, 2008).

Patients with continuous pain from arthritis may develop depression or anxiety. The patient may also have a role change in the family, workplace, or both. To identify changes that have been or need to be made, ask his or her roles before the disease developed. Identify coping strategies to help live with the disease. Ask the patient about his or her expectations regarding treatment for OA.

In addition to role changes, joint deformities and bony nodules often alter body image and self-esteem. Observe the patient’s response to body changes. Does he or she ignore them or seem overly occupied with them? Ask the patients directly how they perceive their body image. Document your assessment findings in the interdisciplinary health care record per agency policy.

Laboratory Assessment

The health care provider uses the history and physical examination to make the diagnosis of OA. The results of routine laboratory tests are usually normal but can be helpful in screening for associated conditions. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) may be slightly elevated when secondary synovitis (synovial inflammation) occurs. The ESR also tends to rise with age, infection, and other inflammatory disorders.

Imaging Assessment

Routine x-rays are useful in determining structural joint changes. Specialized views are obtained when the disease cannot be visualized on standard x-ray film but is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine vertebral or knee involvement.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with osteoarthritis (OA) are:

Planning And Implementation

In 2008, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) group published evidence-based expert consensus guidelines for patients with knee and hip OA (Zhang et al., 2008). These interdisciplinary best practice guidelines have major implications for nursing care and are reflected in the following discussion.

Managing Chronic Pain

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with OA is expected to have pain control that is acceptable to the patient (e.g., at a 3 on a pain intensity scale of 0 to 10).

Interventions.

Optimal management of patients with OA requires drug therapy and nonpharmacologic measures. If these measures are ineffective, surgery may be performed to reduce pain (Zhang et al., 2008). Perform a pain assessment before and after implementing interventions.

Nonsurgical Management.

Management of chronic joint pain is difficult for both the patient and the health care professional. A combination of modalities is often used, including analgesics, rest, positioning, thermal modalities, weight control, and integrative therapies. Chapter 5 elaborates on methods of pain control for chronic pain.

Drug Therapy.

The purpose of drug therapy is to reduce pain caused by cartilage destruction, muscle spasm, and/or secondary joint inflammation. The American Pain Society recommends regular acetaminophen (Tylenol, Atasol ![]() ) as the primary drug of choice because OA is not a primary anti-inflammatory disorder.

) as the primary drug of choice because OA is not a primary anti-inflammatory disorder.

Topical drug applications may help with temporary relief of pain. Prescription lidocaine 5% patches (Lidoderm) have been approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for postherpetic neuralgia (nerve pain) but may also relieve joint pain (especially the knee) for some patients. Teach the patient to apply the patch on clean, intact skin for 12 hours each day. Up to three patches may be applied to painful joints at one time. Remind him or her that Lidoderm can cause skin irritation. Teach the patient that the lidocaine patch is contraindicated in those on class I antidysrhythmics. Topical salicylates, such as OTC Aspercreme patch, gel, or cream, are also useful for some patients as a temporary pain reliever, especially for knee pain.

If acetaminophen or topical agents do not relieve pain, the analgesic drug class of choice may be nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if the patient can tolerate them (see Chart 20-9 later in this chapter). Before beginning NSAID therapy, baseline laboratory information is obtained, including a complete blood count (CBC) and kidney and liver function tests. Celecoxib (Celebrex), a COX-2 inhibitor, is usually the first choice unless the patient has hypertension, renal disease, or cardiovascular disease.

For temporary relief of pain in a single joint, the health care provider may inject an individual joint with cortisone. Patients may have the same joint injected up to four times a year, or once every 3 months. Frequently injected joints include the knee, base of the thumb, shoulder, and trochanteric bursa, which people often call the hip.

Other agents, such as hyaluronate (Hyalgan) and hylan GF 20 (Synvisc), are specific injections for knee and hip pain associated with OA. These synthetic joint fluid implants replace or supplement the body’s natural hyaluronic acid, which is broken down by inflammation and aging.

Muscle relaxants, such as cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride (Flexeril), are sometimes given for painful muscle spasms, especially those occurring in the back from OA of the vertebral column. These drugs should be used with caution in older adults because they can cause acute confusion. Remind the patient not to drive or operate dangerous machinery when taking muscle relaxants.

Nonpharmacologic Interventions.

In addition to analgesics, many nonpharmacologic measures can be used for patients with OA, such as rest balanced with exercise, joint positioning, heat or cold applications, weight control, and a variety of complementary and alternative therapies. Several types of rest are used to treat patients with OA:

Teach the patient to position joints in their functional position. For example, when in a supine position (recumbent), he or she should use a small pillow under the head or neck but avoid the use of other pillows. The use of large pillows under the knees or head may result in flexion contractures. If needed, the legs may be elevated 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 cm) to reduce back discomfort. Remind him or her to use proper posture when standing and sitting to reduce undue strain on the vertebral column. Teach the patient to wear supportive shoes; foot insoles may be helpful to relieve pressure on painful metatarsal joints. Collaborate with the PT to plan a program for muscle-strengthening exercises to better support the joints.

Most patients apply heat or cold for temporary relief of pain, but not all patients find these modalities effective. Heat may help decrease the muscle tension around the tender joint and thereby decrease pain. Suggest hot showers and baths, hot packs or compresses, and moist heating pads. Regardless of treatment, teach him or her to check that the heat source is not too heavy or so hot that it causes burns. A temperature just above body temperature is adequate to promote comfort.

If needed, collaborate with the PT to provide special heat treatments, such as paraffin dips, diathermy (using electrical current), and ultrasonography (using sound waves). A 15- to 20-minute application usually is sufficient to temporarily reduce pain, spasm, and stiffness. Cold packs or gels that feel hot and cold at the same time may also be used.

Cold therapy has limited use for most patients in controlling pain. Cold works by numbing nerve endings and decreasing secondary joint inflammation, if present.

There is no one food that causes or cures arthritis. Instead, a well-balanced diet is recommended. Gradual weight loss for obese patients may lessen the stress on weight-bearing joints, decrease pain, and perhaps slow joint degeneration. If needed, collaborate with the registered dietitian to provide more in-depth teaching and meal planning or make referrals to community resources.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies.

A variety of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies, especially acupuncture, have been effective for some patients (see Chapter 2). Topical capsaicin products may also be used. This expensive OTC drug may work by blocking substance P, a neurotransmitter for pain. Tell the patient to expect a burning sensation for a short time after applying capsaicin. Recommend the use of plastic gloves for application. To prevent burning of eyes or other body areas, wash hands immediately after applying the substance.

Dietary supplements may complement traditional drug therapies. Glucosamine and chondroitin are widely used and are the most effective nonprescription supplements taken to decrease pain and improve functional ability (Zhang et al., 2008). These natural products are found in and around bone cartilage for repair and maintenance. Glucosamine may decrease inflammation, and chondroitin may play a role in strengthening cartilage. These supplements may be used topically or taken in oral form. If no improvement is evident in 6 months of use, they should be discontinued (Zhang et al., 2008). Chart 20-1 summarizes what you should teach your patients about glucosamine, with or without chondroitin.

Surgical Management.

Surgery may be indicated when conservative measures no longer provide pain control, when mobility becomes so restricted that the patient cannot participate in activities he or she enjoys, and when he or she cannot maintain the desired quality of life. The most common surgical procedure performed for older adults with OA is total joint arthroplasty (TJA) (surgical creation of a joint), also known as total joint replacement (TJR). Almost any synovial joint of the body can be replaced with a prosthetic system that consists of at least two parts, one for each joint surface. TJAs are expected to increase exponentially as baby boomers age over the next 20 years.

A less invasive procedure using arthroscopy may be used to remove damaged cartilage (see Chapter 52). An osteotomy (bone resection) may be performed to correct joint deformity, but this procedure is done most commonly for younger adults (Zhang et al., 2008).

Indications for Total Joint Arthroplasty.

Total joint arthroplasty is a procedure used most often to manage the pain of OA and to improve mobility, although other conditions causing cartilage destruction may require the surgery. These disorders include RA, congenital anomalies, trauma, and osteonecrosis. Osteonecrosis is bony necrosis secondary to lack of blood flow, usually from trauma or chronic steroid therapy. Hip and knee joints are most commonly replaced, but finger and wrist joint, elbow, shoulder, toe joint, and ankle replacements have been improved in the past 15 years.

Contraindications to Total Joint Arthroplasty.

The contraindications for TJA are active infection anywhere in the body, advanced osteoporosis, and rapidly progressive inflammation. An infection elsewhere in the body or from the joint being replaced can result in an infected TJA and subsequent prosthetic failure. Therefore if a patient has a urinary tract infection, for example, the physician treats the infection before surgery. Advanced osteoporosis can cause bone shattering during insertion of the prosthetic device. Severe medical problems, such as uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension, put the patient at risk for major postoperative complications and possible death.

As a group, TJAs are very successful. Many patients who have lived with chronic, unbearable pain for years and could not function independently at home or in the workplace no longer experience pain in the diseased joint. The pain relief and psychological benefit often outweigh the perioperative risks and costs, but the surgeon and patient must make that decision. When the patient is older than 85 years, this decision may become an ethical issue in addition to a physical risk and cost-versus-benefit decision.

Total Hip Arthroplasty.

The number of total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures (also known as total hip replacement [THR]) has steadily increased over the past 30 years. The first time a patient receives any total joint arthroplasty, it is referred to as primary arthroplasty. If the implant loosens, revision arthroplasty may be performed. Availability of improved joint implant materials and better custom design features allow longer life of a replaced hip. Although patients of any age can undergo THR, the procedure is performed most often in those older than 60 years. The special needs and normal physiologic changes of older adults often complicate the perioperative period and may result in additional postoperative complications.

Preoperative Care.

As with any procedure, preoperative care begins with assessing the patient’s level of understanding about the surgery and his or her ability to participate in the postoperative plan of care. The surgeon explains the procedure and postoperative expectations (including possible complications) during the office visit, but this patient education may have occurred weeks or months before the scheduled surgery. Some patients may not know what questions to ask or may forget the important information that was taught. Information may be provided in a notebook or DVD format that the patient can take home to review and share with family. This is particularly useful to patients with poor reading skills or poor memory. Written materials or other media provided in the patient’s language appropriate for the patient’s educational level are essential.

An interdisciplinary plan of care that outlines expectations during preadmission, hospitalization, and posthospitalization phases of care should be reviewed with the patient and family or significant other. Thomas and Sethares (2008) investigated the effects of preoperative interdisciplinary patient education for patients having total hip or knee arthroplasty using a large quasi-experimental design. The researchers found that postoperative patients in the intervention group had a higher knowledge level than those patients who did not receive the structured preoperative education. A study by Almada and Archer (2009) described the positive outcomes for joint arthroplasty patients who were visited by an RN before and after surgery. Part of both visits included patient and family/caregiver education.

In some hospitals or orthopedic office practices, the physical therapist (PT) may have the patient practice transfers, positioning, and ambulation. An occupational therapist (OT) may partner with the PT to assist in exercises or learning to ambulate with an assistive device, such as crutches or a walker. In a systematic review of three available studies, Barbay (2009) found that preoperative exercises for patients having hip or knee arthroplasty had some benefits in improving postoperative outcomes, but the results were inconclusive.

The OT may also help obtain assistive/adaptive equipment that will be needed after surgery. The cost of some items, such as an elevated toilet seat, is covered by Medicare and other insurers because they are essential to prevent hip dislocation. Other helpful equipment may not be paid for by third-party payers and can be purchased at local pharmacies or medical supply stores, based on the patient’s specific needs. Examples include:

All patients are also told to visit a dentist and have any necessary dental procedures done before surgery. After surgery, he or she must take extreme care not to acquire an infection that could migrate to the surgical area and cause prosthetic failure. Remind the patient to tell any future health care provider that he or she has had a THA.

In addition to usual preoperative laboratory tests, the surgeon may ask the patient with RA to have a cervical spine x-ray if he or she is having general anesthesia. Those with RA often have cervical spine disease that can lead to subluxation during intubation. Hip x-rays, computed tomography (CT) scan, and/or MRI may be done to assess the operative joint and surrounding soft tissues.

Because venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a serious postoperative complication, especially for hip surgery, the patient’s risk factors for clotting problems are assessed, including history of previous clotting, obesity, smoking, and advanced age. Drugs that increase the risks for clotting and bleeding, such as NSAIDs, vitamins C and E, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), are discontinued about a week before surgery.

Patients are also assessed for the need for possible blood transfusion after surgery. For patients who are at risk for postoperative anemia, one or more blood transfusions may be needed. Autologous (patient’s own) or banked blood can be used. If desired, the patient may donate blood several weeks before surgery to be used after surgery. This pre-deposit autologous blood donation is a safe and cost-effective blood replacement alternative for those who are undergoing elective surgeries. It also decreases the risk for blood transfusion reactions.

For some patients, the surgeon may prescribe several weeks of epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit, Eprex ![]() ) with or without iron to prevent anemia that can occur after hip or knee replacement. Epoetin alfa is recombinant human erythropoietin, a substance that is essential for developing red blood cells. This drug is particularly useful for older adults, who frequently have mild anemia before surgery.

) with or without iron to prevent anemia that can occur after hip or knee replacement. Epoetin alfa is recombinant human erythropoietin, a substance that is essential for developing red blood cells. This drug is particularly useful for older adults, who frequently have mild anemia before surgery.

Remind patients that they will likely be asked to take a shower with special antiseptic soap the night before surgery to decrease bacteria that could cause infection after surgery. Tell them to wear clean nightwear after their shower and sleep on clean linen. Review which drugs are safe to take or necessary the morning of the operation, such as antihypertensives, and which ones should be avoided. Medication should be taken with a very small amount of water.

Operative Procedures.

Similar to other orthopedic surgeries, the patient receives an IV antibiotic, usually a cephalosporin such as cefazolin (Ancef), at least 1 hour before the initial surgical incision is made or during the THA. Other drugs may be used for those who are allergic to cephalosporins.

The anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist places the patient under general or neuroaxial (epidural/spinal) anesthesia for lower extremity surgery. Neuroaxial induction reduces blood loss and the incidence of deep vein thrombosis. Intraoperative blood loss with hypotensive neuroaxial anesthesia is usually less than that with general anesthesia, thereby decreasing the need for postoperative blood transfusions.

Several types of incisions for hip replacement may be used. The more traditional 8-inch (20-cm) incision is usually longitudinal on the anterolateral thigh. The anterolateral approach results in more damage to muscle but less risk for dislocation. A posterior incision, posterolateral on the thigh and into the buttock, may be used to preserve muscle but may increase the risk for dislocation and sciatic nerve injury.

Some patients are candidates for minimally invasive surgery (MIS) using a smaller incision with special instruments to reduce muscle cutting. This newer technique cannot be used for patients who are obese or those with osteoporosis. It is done only for primary THAs, not for revision surgeries. Like those of any MIS, the benefits of minimally invasive THA are decreased soft tissue damage and postoperative pain. Patients often have a shorter hospital stay and quicker recovery. They are generally satisfied with the cosmetic appearance of the incision because there is less scarring. Postoperative complications are not as common in patients having minimally invasive (“mini”) hip replacements when compared with those having the traditional technique.

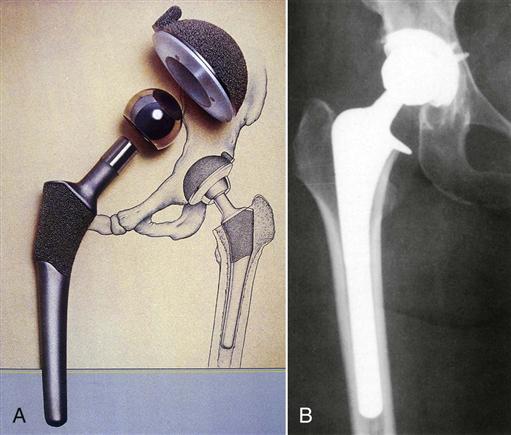

Regardless of procedure type, two components are used in the THA—the acetabular component and the femoral component (Fig. 20-2). A non-cemented prosthesis is most often used. Bone surfaces are smoothed as they are prepared to receive the artificial components. The non-cemented components are press-fitted into the prepared bone. The acetabular cup may be placed using computer assistance. If the prosthesis is cemented, polymethyl methacrylate (an acrylic fixating substance) is used. A closed wound drainage system may be placed in the wound before the surgeon closes the incision.

Considerations of a non-cemented prosthesis include protection of weight-bearing status to allow bone to grow into the prosthesis and decreased problems with loosening of the prosthesis. With a cemented prosthesis, cement can fracture or deteriorate over time, leading to loosening of the prosthesis, which causes pain and can lead to the need for a revision arthroplasty. In revision arthroplasty, the old prosthesis is removed and new components are replaced. Bone graft may be placed if bone loss is significant. Outcomes from revision arthroplasty may not be as positive as with primary arthroplasty.

Postoperative Care.

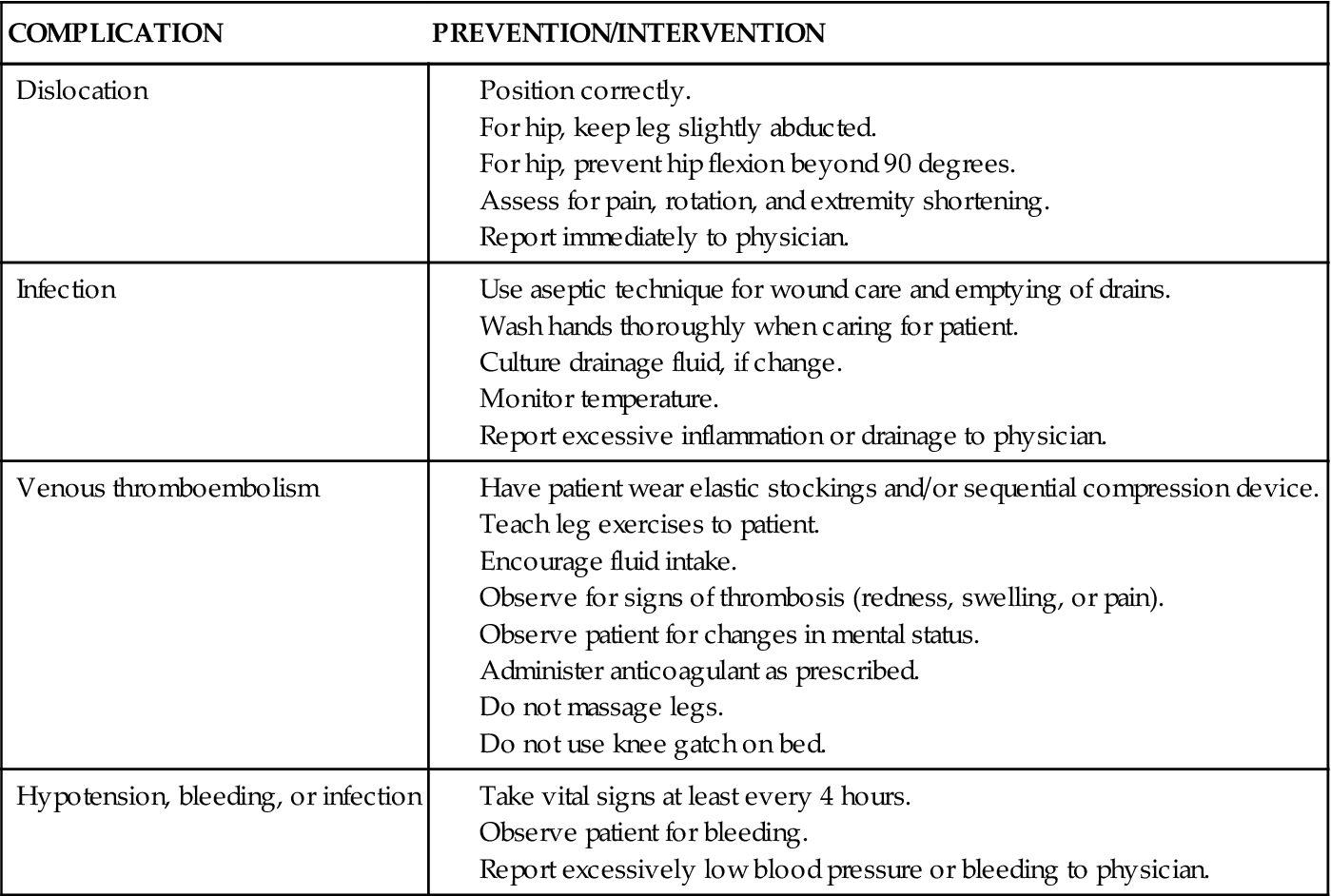

In addition to providing the routine postoperative care discussed in Chapter 18, assess for and help prevent possible postoperative complications. Table 20-2 summarizes these complications, including nursing measures for prevention, assessment, and intervention. Chart 20-2 highlights special concerns for the care of older adults in the postoperative period. Collaborate with your patient and his or her family to become safety partners to keep the patient free from harm, including complications, such as:

TABLE 20-2

NURSING INTERVENTIONS TO PREVENT COMPLICATIONS OF TOTAL JOINT ARTHROPLASTY

| COMPLICATION | PREVENTION/INTERVENTION |

| Dislocation | |

| Infection | |

| Venous thromboembolism | |

| Hypotension, bleeding, or infection |

Preventing Hip Dislocation.

A major complication of THA is subluxation (partial dislocation) or total dislocation.

In some hospitals, abduction devices with straps are placed on patients who are restless or cannot follow instructions, especially older adults with delirium or dementia. One or two regular bed pillows are used in most cases to remind patients to keep their legs abducted. For devices with straps, be sure to loosen the straps every 2 hours and check the patient’s skin for irritation or breakdown.

Place and support the affected leg in neutral rotation. Keep the patient’s heels off the bed to prevent skin breakdown, particularly older adults. The procedure for postoperative turning is controversial and specified by agency policy or surgeon preference. In most cases, you are safe to turn the patient if the pillow is in place. Some surgeons allow only turning directly onto one side or the other, depending on the surgical approach.

Teach the patient and family about other precautions to prevent dislocation as outlined in Chart 20-3. In addition to preventing adduction, remind them that the patient should avoid flexing the hips more than 90 degrees at all times. Use diagrams or demonstrate correct positioning to help reinforce this information before the patient gets out of bed (Fig. 20-3).

If the hip is dislocated, the surgeon manipulates and relocates the affected hip after the patient receives moderate sedation. The hip is then immobilized by an abduction splint or other device until healing occurs—usually in about 6 weeks.

Preventing Venous Thromboembolism.

The most potentially life-threatening complication after THA is venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Older patients are especially at increased risk for VTE because of age and decreased circulation before surgery. Obese patients and those with a history of VTE are also at high risk for thrombi. Sequential compression devices and/or antiembolism stockings are typically applied.

Anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin, Warfilone ![]() ), subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or factor Xa inhibitors, help prevent VTE. Patients are usually on anticoagulants for 3 to 6 weeks after surgery, depending on the patient’s response and risk factors. During the past 20 years, the use of LMWHs has markedly increased for patients with total hip and knee replacements. Examples include enoxaparin (Lovenox), dalteparin (Fragmin), and tinzaparin (Innohep). These drugs work to inhibit factor Xa, which is a key component in the clotting process. Given in a low prophylactic dose based on the patient’s weight, they do not significantly affect prothrombin time (PT) or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

), subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or factor Xa inhibitors, help prevent VTE. Patients are usually on anticoagulants for 3 to 6 weeks after surgery, depending on the patient’s response and risk factors. During the past 20 years, the use of LMWHs has markedly increased for patients with total hip and knee replacements. Examples include enoxaparin (Lovenox), dalteparin (Fragmin), and tinzaparin (Innohep). These drugs work to inhibit factor Xa, which is a key component in the clotting process. Given in a low prophylactic dose based on the patient’s weight, they do not significantly affect prothrombin time (PT) or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Although not as commonly seen with these drugs when compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH), thrombocytopenia (decreased platelets) can occur. Therefore monitor the patient’s complete blood count and platelet count per agency policy. Assess for bleeding, including occult blood in stool and bruising. Protamine sulfate can be given as an antidote for all heparins; however, it is not as effective for LMWH when compared with UFH. Be especially alert for signs and symptoms of neurologic dysfunction because spinal and epidural hematomas can occur in patients who received neuroaxial anesthesia.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra), a factor Xa inhibiting agent, may also be prescribed for patients undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty. Its action is similar to that of LMWHs and has no effect on coagulation tests. Like other drugs, however, the patient is at risk for bleeding. No antidote exists at this time for fondaparinux. Like LMWHs, Arixtra is given for several days with an overlap while anticoagulants begin to work. A complete discussion of nursing care associated with patients taking anticoagulants and VTE is found in Chapter 38. The Joint Commission’s VTE Core Measures are also discussed in that chapter.

Early ambulation and exercise help prevent VTE. Teach the patient about leg exercises, which should begin in the immediate postoperative period and continue through the rehabilitation period. These exercises include plantar flexion and dorsiflexion (heel pumping), circumduction (circles) of the feet, gluteal and quadriceps muscle setting, and straight-leg raises (SLRs). Teach the patient to perform gluteal exercises by pushing the heels into the bed and achieve quadriceps-setting exercises (“quad sets”) by straightening the legs and pushing the back of the knees into the bed. In addition to preventing clots, these exercises improve muscle tone, which helps restore the function of the extremity.

Preventing Infection.

Another potential complication of hip replacement is infection. Infection can occur during hospitalization or months or years later. Most infections are caused by contamination during surgery.

Monitor the surgical incision and vital signs carefully—every 4 hours for the first 24 hours and every 8 to 12 hours thereafter. Observe for signs of infection, such as an elevated temperature and excessive or foul-smelling drainage from the incision. An older patient may not have a fever with infection but, instead, may experience an altered mental state. If you suspect infection, obtain a sample of any drainage for culture and sensitivity to determine the offending organisms and the antibiotics that may be needed for treatment.

Assessing for Bleeding and Managing Anemia.

Observe the surgical hip dressing for bleeding or other type of drainage at least every 4 hours or when vital signs are taken. Empty and measure the bloody fluid in the surgical drain(s) every shift. The total amount of drainage is usually less than 50 mL/8 hr. Patients who have the minimally invasive procedure may not have a drain. The surgeon usually removes the drains and operative dressing 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Take special care when removing tape from the skin to prevent tape burns as the surgical dressing is changed, especially for older adults.

The surgeon also requests periodic hemoglobin and hematocrit (H&H) tests to assess for anemia. Although some patients receive several units of blood during surgery, the H&H levels may continue to fall; in this case, additional blood is given 1 to 2 days after surgery. Blood pressure may be lower than usual because of blood loss during surgery.

Assessing for Neurovascular Compromise.

As with other musculoskeletal surgery, monitor neurovascular assessments frequently for a possible compromise in circulation to the affected distal extremity.

In addition to implementing interventions to prevent potential postoperative complications and monitoring for early signs of complications, the interdisciplinary team plans care to manage pain, improve mobility and activity, and promote self-management.

Managing Pain.

Although hip arthroplasty is performed to relieve joint pain, patients experience pain related to the surgical procedure. Many state that their pain is different and less severe than before surgery. Immediate pain control is typically achieved by extended-release epidural morphine (EREM) or patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine or another opioid. A study by Smith-Miller et al. (2009) found that there was no difference in pain control when these two methods were compared. Chapter 5 contains information on the nursing care associated with these acute pain modalities. Keep in mind that the patient may also receive other analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic arthritic pain in other joints.

Regardless of the pain management method used, most patients do not require parenteral analgesics after the first day. Oral opioids, such as oxycodone plus acetaminophen (Percocet, Tylox), are then commonly prescribed until the pain can be controlled by NSAIDs such as ketorolac (Toradol, Acular) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Apo-Ibuprofen ![]() ).

).

Nonpharmacologic methods for acute and chronic pain control can also be used to decrease the amount of drug therapy used (see Chapter 5). A study by Thomas and Sethares (2010) found that guided imagery can be helpful in controlling pain in patients with total joint arthroplasty.

Promoting Mobility and Activity.

Depending on the time of day that the surgery is performed, the patient with a THA usually gets out of bed the night of surgery to prevent complications (e.g., atelectasis, pneumonia), especially in older adults.

Remind the patient to avoid flexing the hips beyond 90 degrees as discussed earlier (see Fig. 20-3). Raised toilet seats and reclining chairs help prevent hyperflexion of the replaced hip joint. Be sure to teach the patient to also avoid twisting the body or crossing his or her legs to prevent hip dislocation.

The surgeon, type of prosthesis, and surgical procedure determine the amount of weight bearing that can be applied to the affected leg. A patient with a cemented implant is usually allowed immediate partial weight bearing (PWB) and progresses to full weight bearing (FWB). Typically, only “toe-touch” or minimal weight bearing is permitted for patients with uncemented prostheses. When x-ray evidence of bony ingrowth can be seen, the patient can progress to PWB and then to FWB.

In collaboration with the physical therapist (PT), teach the patient how to follow weight-bearing restrictions. Most patients use a walker (may be a rolling walker), but younger adults may use crutches. They are usually advanced to a single cane or crutch if they can walk without a severe limp 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. When the limp disappears, they no longer need an ambulatory/assistive device and may be permitted to sit in chairs of normal height, use regular toilets, and drive a car.

Promoting Self-Management.

The hospital’s occupational therapy department often supplies assistive/adaptive devices to help with ADLs, especially for those having traditional surgery. Particularly important are devices designed for reaching to prevent patients from bending or stooping and flexing the hips more than 90 degrees. Extended handles on shoehorns and dressing sticks may be very useful to achieve ADL independence. Third-party payers may or may not pay for these devices, depending on the patient’s status.

For those who have traditional surgery, the length of stay in the acute care hospital is typically 3 days, but older adults or those experiencing postoperative complications may stay longer. Those who have the minimally invasive THA are discharged on the second postoperative day or the day of surgery (23-hour stay). Those patients are discharged to home on crutches to practice their own rehabilitative exercises. Most of them are able to return to work in 2 weeks. For that reason, some hospitals have started Rapid Recovery Hip Replacement programs for patients who are candidates for MIS.

Discharge for patients having traditional surgery may be to the home, a rehabilitation unit, a transitional care unit, or a skilled unit or long-term care facility for continued rehabilitation before discharge to home. The interdisciplinary team provides written instructions for posthospital care and reviews them with patients and their family members (see Chart 20-3). Be sure to provide a copy of these instructions for the patient.

Acute rehabilitation usually takes 1 to 2 weeks or longer, depending on the patient’s age and tolerance and the type of prosthesis used. However, it often takes 6 weeks or longer for complete recovery. Some patients who are discharged to their home are able to attend physical therapy sessions in an office or ambulatory care setting. Others have no means or cannot use community resources and need physical therapy in the home, depending on their health insurance coverage. Collaborate with the case manager to determine which option is best for your patient.

Total Knee Arthroplasty.

Although many adults require total knee arthroplasty (TKA, also known as total knee replacement [TKR]), those who have a knee replaced are often younger than those who have a hip replaced. Continued improvements in total knee implants in the past 15 years have increased the expected life of a TKA to 20 years or more, depending on the age and activity level of the patient. An increasing number of patients who have TKAs are overweight or obese. Obesity increases wear and tear on weight-bearing joints, which can lead to revision surgeries. Unilateral (one joint) or bilateral joint replacements done at the same time may be performed, depending on the patient.

Preoperative Care.

TKA, like hip replacement, is performed when joint pain cannot be managed by conservative measures. When activity and mobility severely prevent patients from participating in work or activities they enjoy, this procedure can restore a high quality of life. The preoperative care and teaching for patients undergoing a TKA are similar to that for total hip replacement. However, precautions for positioning are not the same. Differences in patient and family teaching depend on the procedure used by the orthopedic surgeon.

Like the minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for the hip, the knee can also be replaced using MIS. Candidates for mini–knee replacement cannot have severe bone loss, obesity, or previous knee surgery. They should be in good general health. Patients having MIS usually have less blood loss during surgery, less pain, more joint range of motion (less stiffness from scarring), and a faster recovery, leading to a shorter hospital stay. Rapid Recovery Knee Replacement programs for patients having minimally invasive TKA are becoming popular in a number of hospitals.

All patients are given verbal and either written or video preoperative instructions, which include the activity protocol to follow after surgery. The PT and OT provide information about transfers, ambulation, postoperative exercises, and ADL assistance. Patients may practice walking with walkers or crutches to prepare them for ambulation after TKA. Teach patients about the possible need for assistive-adaptive devices to assist with ADLs, including an elevated toilet seat, safety handrails, and dressing devices like a long-handled shoehorn. Some third-party payers cover these devices, depending on the patient’s condition and age; however, other insurers may not pay for them. Teach the patient and family where this equipment can be purchased to have it available after surgery.

Some surgeons prescribe a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine after knee surgery to increase joint mobility. Others have found that the range of motion for the surgical knee is not improved by using this device. If the patient will have a CPM machine after surgery, be sure to explain what it is and how it is used.

Routine diagnostic testing is requested, as well as any additional tests, such as cervical spine x-rays for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to determine if the patient can be intubated for anesthesia. Knee x-rays, CT scan, and/or MRI may be done to assess the joint and surrounding soft tissues.

Teach patients that they will need to shower with a special antiseptic soap the night before surgery to decrease bacteria on the skin that could cause infection after surgery. Remind them to wear clean nightwear and sleep on clean linen. Ask them to check with their surgeon about what medications they can take the morning of surgery, including antihypertensives. Take these drugs with a small amount of water to prevent vomiting and aspiration during surgery.

Operative Procedures.

As with the hip, the knee can be replaced with the patient under general or neuroaxial (epidural or spinal) anesthesia. An antibiotic, usually an IV cephalosporin, is given shortly before surgical opening. In the traditional surgery, the surgeon makes a central longitudinal incision about 8 inches (20 cm) long. Osteotomies of the femoral and tibial condyles and of the posterior patella are performed, and the surfaces are prepared for the prosthesis. The femoral component is often non-cemented (using a press-fit) with the tibial component being cemented. The surgeon typically inserts a surgical drain and applies a pressure dressing to decrease edema and bleeding.

Minimally invasive TKA may be performed using a shorter incision and special instruments to spare muscle and other soft tissue. Computer-guided equipment may be used to ensure accurate positioning of the knee implants. This procedure is referred to as a computer-assisted TKA.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies.

An experimental treatment to reduce the severe pain that occurs after knee arthroplasty is the intraoperative insertion of Adlea, a refined capsaicin product, directly into the surgical joint. Capsaicin binds to and opens C fiber receptors, especially TRPV1, which causes extra calcium to enter the nerve cells. The cells become overloaded and shut down, causing numbness. Preliminary results from several studies show that patients who were given Adlea during knee surgery had less acute postoperative pain when compared with others who did not receive the treatment. Additional studies for patients having total hip replacements and bunionectomies are currently being conducted. Adlea could help decrease the need for opioid analgesia for many patients having surgery (Remadevi & Szallisi, 2008).

Postoperative Care.

Postoperative nursing care of the patient with a TKA is similar to that for the patient with a total hip arthroplasty; however, maintaining hip abduction is not necessary. The surgeon may prescribe a CPM machine, which can be applied in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) or soon after the patient is admitted to the postoperative unit (Fig. 20-4). The CPM machine keeps the prosthetic knee in motion and may prevent the formation of scar tissue, which could decrease knee mobility and increase postoperative pain. In the immediate postoperative period, the surgeon may also prescribe ice packs or other cold therapy to decrease swelling at the surgical site. Swelling and bruising are more common with this type of surgery than with hip surgery.

The surgeon, PT, or technician presets the CPM machine for the appropriate range of motion and cycles per minute. A typical initial setting is 20 to 30 degrees of flexion and full extension (0 degrees) at two cycles per minute, but this setting varies according to surgeon preference. The machine is generally used on an intermittent schedule of a designated number of hours several times a day, with the range of motion increased gradually. Observe and document the patient’s response to the device, and follow the surgeon’s protocol for settings. Chart 20-4 outlines your responsibility when caring for a patient using the CPM machine.

In general, pain-control measures for patients with TKA are similar to those with total hip arthroplasty. Many patients report high ratings on the pain intensity scale and require IV opioid medications longer than patients with THA, particularly if they have had bilateral surgery. Be sure to manage your patient’s pain to provide comfort, increase his or her participation in physical therapy, and improve joint mobility.

One of the most recent advances in postoperative pain management for lower extremity total joint arthroplasty is peripheral nerve blockade (PNB). In this procedure, the anesthesiologist injects the femoral or sciatic nerve with local anesthetic; the patient may receive a continuous infusion of the anesthetic by portable pump. This method of pain management not only decreases pain but also allows patients to participate in rehabilitation earlier than when using opioid analgesia alone. Patients having continuous femoral nerve blockade (CFNB) after TKA require less opioids and antiemetics when compared with patients receiving no CFNB and those who had a single-shot FNB. A study by Leach and Bonfe (2009) also found that patients with nerve blocks had better flexion and extension of the knee when compared with those who had either general or epidural/spinal anesthesia.

When caring for a patient receiving a CPNB, perform neurovascular assessments every 2 to 4 hours or according to hospital protocol. The patient should be able to plantar flex and dorsiflex the affected foot but not feel pain in the extremity. Check for movement, sensation, warmth, color, pulses, and capillary refill.

Because dislocation is a rare problem for a patient with TKA, special positioning to prevent adduction is not required. Maintain the knee in a neutral position and not rotated internally or externally. If a CPM machine is not used, the surgeon may recommend that the knee should rest flat on the bed or with one pillow under the lower calf and foot to encourage slight extension of the knee joint. Be sure that the surgical knee does not hyperextend.

Some complications that affect patients with total hip arthroplasty may also affect those having TKA, such as venous thromboembolism, infection, anemia, and neurovascular compromise. Assessments and interventions associated with these complications are described in the Postoperative Care section of the discussion of Total Hip Arthroplasty on pp. 325-328.

The desired outcome for discharge from the acute hospital unit is that the patient can walk independently with crutches, walker, or cane and has adequate flexion in the operative knee for ambulation. Patients who had minimally invasive TKA are discharged to home in 2 days with instructions for postoperative exercises, weight bearing, and activity progression. Many of these instructions (except for preventing hip dislocation) are similar to those provided for teaching patients after a total hip arthroplasty (see Chart 20-3).

Patients are able to partially weight bear unless the prosthesis is not cemented. During the home rehabilitation phase, the use of a stationary bicycle or CPM machine may help gain flexion. These patients can return to work and other usual activities in 2 to 3 weeks, depending on their age and other health status factors.

Acute rehabilitation for traditional TKA usually takes about 1 to 2 weeks longer, depending on the age and tolerance of the patient. These patients may be discharged to their home or to an acute rehabilitation unit, transitional care unit, skilled unit, or long-term care facility for therapy. If able, they may attend physical therapy sessions in an office or ambulatory care setting. If not, home care services can provide physical therapy in their home, depending on the insurance available. Collaborate with the case manager to determine which option is best for your patient. Total recovery from traditional TKA takes 6 weeks or longer, especially for those older than 75 years.