Chapter 17 Care of Intraoperative Patients

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Use appropriate patient identifiers when administering drugs or marking surgical sites.

2. Verify that the patient has given informed consent for the surgical procedure.

3. Examine individual patient factors for potential threats to safety, especially for older adults.

4. Differentiate the roles and responsibilities of intraoperative personnel.

5. Understand the principles of infection prevention as they apply to aseptic technique in setting up a sterile field.

6. Explain correct technique to apply and remove surgical attire.

7. Understand the nurse’s role in monitoring all OR personnel for possible breaks in sterile technique.

8. Apply nursing interventions to reduce patient and family anxiety.

9. Explain procedures to ensure the identity of the patient and the accuracy of the planned surgical procedure.

10. Act as a patient advocate with regard to patients’ rights, informed consent, and advance directives.

11. Apply interventions to ensure the patient’s safety and dignity during an operative procedure.

12. Assess patients for specific problems related to positioning during surgical procedures.

13. Understand anatomic principles for modifying patient positioning and OR bed padding to prevent skin breakdown, promote comfort, and prevent positioning injury during surgical procedures.

14. Coordinate appropriate care for the patient with malignant hyperthermia.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The intraoperative period begins when the patient enters the surgical suite and ends at the time of transfer to the postanesthesia recovery area, same-day surgery unit, or the intensive care unit. The main concerns of perioperative nurses are the safety and advocacy for the patient during surgery. Nursing observations and actions can prevent, reduce, control, and manage many hazards. Once in the operating room (OR), the patient is at risk for infection, impaired skin integrity, increased anxiety, altered body temperature, and injury related to positioning and other hazards. The surgical phase is filled with unfamiliar experiences and uncertain outcomes. Nursing care during this period is critical because the patient’s physical needs, spiritual needs, comfort, safety, dignity, and psychological status depend on the perioperative nurse. Specific procedures and policies may differ among agencies but should all reflect the perioperative standards and recommended practices as published by the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) (2010a). Perioperative nurses practice within a specific, patient-focused model that incorporates professional practice with attainable, measurable outcomes.

Overview

Members of the Surgical Team

Anesthesia Providers

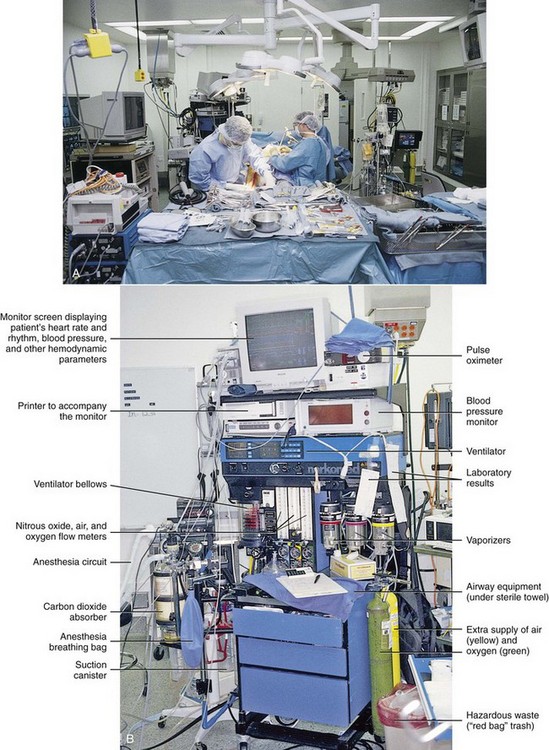

The anesthesia provider monitors the patient during surgery by assessing and monitoring:

• The level of anesthesia (i.e., by using a peripheral nerve stimulator or electroencephalogram [EEG] bispectral analysis)

• Cardiopulmonary function (using electrocardiographic [ECG] monitoring, pulse oximetry, end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, arterial blood gases [ABGs], and hemodynamic monitoring via arterial lines and/or pulmonary artery catheters)

• Capnography (monitors ventilation for non-intubated patients)

Perioperative Nursing Staff

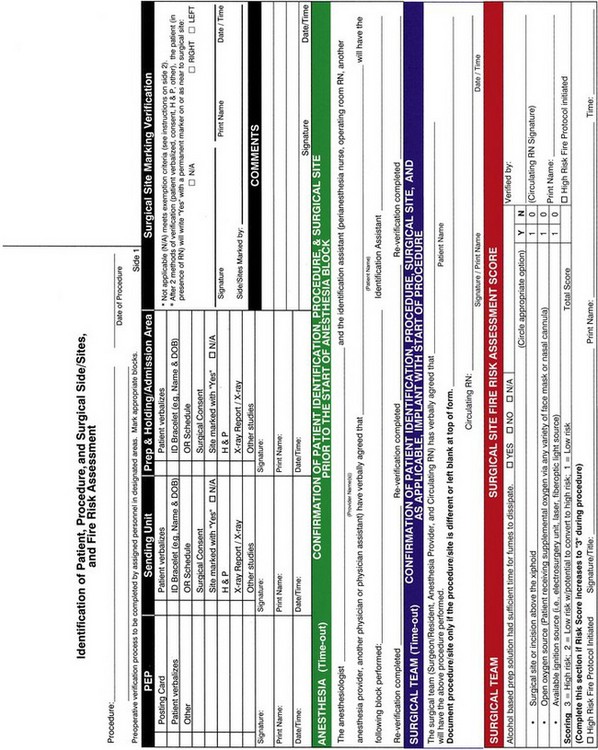

Holding area nurses work in those operating suites that have a presurgical holding area next to the main ORs. The patient waits in this area until the OR is ready. The holding area nurse coordinates and manages the care while the patient is in this area. Responsibilities include greeting the patient on arrival, reviewing the medical record and preoperative checklist, verifying that the operative consent forms are signed, and documenting the risk assessment (Fig. 17-1). This nurse also assesses the patient’s physical and emotional status, gives emotional support, answers questions, and provides additional education as needed.

Circulating nurses or “circulators” are registered nurses who coordinate, oversee, and are involved in the patient’s nursing care in the OR. The circulating nurse’s actions are vital to the smooth flow of events before, during, and after surgery. He or she is responsible for coordinating all activities within that particular OR. The circulator sets up the OR and ensures that supplies, including blood products and diagnostic support, are available as needed. All anticipated equipment is gathered and inspected by the circulator to make certain that it is safe and functional before the surgery. Depending on the procedure and position required, the circulator makes up the operating bed (OR table) with gel pads (to prevent pressure ulcers), safety straps and armboards (for patient positioning), and either heating pads under the sheets or disposable warming blankets placed over the patient as indicated (to prevent hypothermia) (Weirich, 2008).

Throughout the surgery, the circulating nurse:

• Protects the patient’s privacy

• Ensures the patient’s safety

• Monitors traffic in the room

• Assesses the amount of urine and blood loss

• Reports findings to the surgeon and anesthesia provider

• Ensures that the surgical team maintain sterile technique and a sterile field

• Anticipates the patient’s and surgical team’s needs, providing supplies and equipment

• Communicates information about the patient’s status to family members during long or unique procedures

Scrub nurses or scrub persons set up the sterile table (Fig. 17-2), drape the patient, and hand sterile supplies, sterile equipment, and instruments to the surgeon and the assistant. Knowledge of the surgical procedure allows the scrub person to anticipate which instruments and types of sutures the surgeon will need. Anticipating these needs reduces the duration of anesthesia for the patient. In addition, the surgeon’s anxiety and tension are reduced when the scrub nurse or person is familiar with the procedure and can anticipate and respond accordingly. Throughout the surgical procedure, the scrub person (with the circulating nurse) maintains an accurate count of sponges, sharps, and instruments and amounts of irrigation fluid and drugs used.

If the facility uses laser technology, a nurse specially trained in the use, care, and maintenance of the laser is needed. He or she may be called a laser specialty nurse or a laser nurse coordinator. (Laser is an acronym for light amplification by the stimulated emission of radiation.) A laser gives off a high-powered beam of light that cuts tissue more cleanly than do scalpel blades. This process creates intense heat, rapidly clots blood vessels or tissue, and turns target tissue (e.g., a tumor) into vapor. All personnel must observe safety measures (e.g., wear eye shields, read door signs) during laser procedures to prevent injury to the patient and staff (AORN, 2010h).

Psychosocial Integrity

A. Administering the preoperative medication as soon as possible.

B. Assuring the client that his scheduled surgery is routine and that nothing will go wrong.

C. Determining whether the client wants family members to be with him in the holding area.

D. Explaining to the client that this hospital’s surgical area is the most technologically advanced in the city.

Preparation of the Surgical Suite and Team Safety

The nurse ensures electrical safety through proper placement of grounding pads and use of electrical equipment that meets safety standards. All equipment used during surgery must be functional and in proper working condition as determined by the safety procedure of that facility. Equipment is cleaned and, when required, sterilized so that it can be used as a part of the procedure. The scrub and circulating nurses together ensure a correct count of surgical instruments, sharps, and sponges. Counts are performed before the procedure, during the procedure as items are added or at the time personnel are relieved from that assignment, at closure of the first layer of the surgical wound, and immediately before complete skin closure (AORN, 2010l; Jackson & Brady, 2008).

Layout

Fig. 17-3 shows a typical OR. The exact number of tables and equipment used in a room is based on the needs of each patient. A communication system links the OR and the main desk of the surgical suite. The system includes an intercom with separate systems for routine and emergency calls.

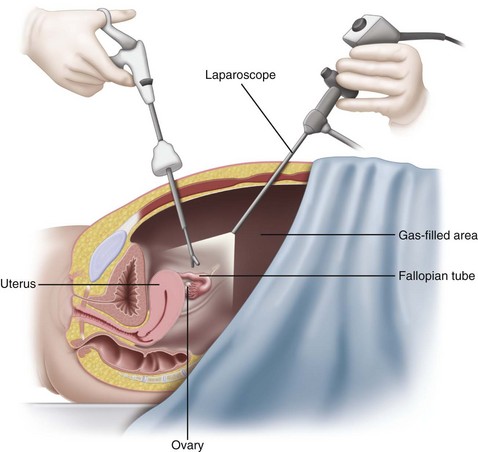

Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

MIS involves making one or more small incisions in the area of the surgery and placing an endoscope through the opening. An endoscope is a tube that allows viewing and manipulation of internal body areas (Fig. 17-4). Some endoscopes also magnify the view. These instruments may be rigid, semirigid, or flexible. Some have light sources, whereas others require that a separate light source be inserted into the surgical area. Endoscopes have different names and shapes for different surgical purposes. For example, laparoscopes are used for abdominal surgery, arthroscopes are used for joint surgery, and ureteroscopes are used for urinary tract surgery.

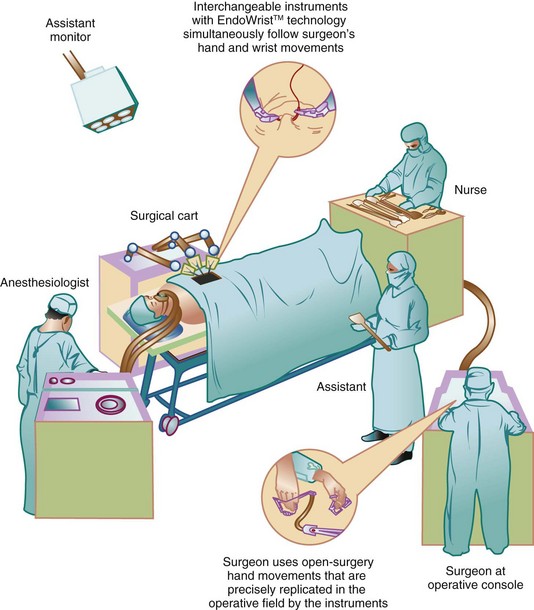

Robotic technology is drastically changing how surgery is performed and how the OR is organized. Robotic surgery takes minimally invasive surgery to a new level. Many gynecologic, urologic, and cardiovascular procedures are being performed by using robotics. The robotic system consists of several components (Fig. 17-5). These include a console, surgical arm cart, and video cart. Initially, the surgeon inserts the required instruments and positions the articulating arms; he or she then breaks scrub and performs the surgery while sitting at the console. A three-dimensional (3-D) view of the patient’s anatomy provides the surgeon with precise control and dexterity. The vision cart holds the monitors, cameras, and recorder equipment. This new technology requires a perioperative robotics nurse specialist who provides education for patients and family and training for members of the surgical team.

Mechanical trauma and thermal injury are two categories of injury that a patient can incur during MIS and robotic surgery (Ulmer, 2010). One limitation for both minimally invasive surgery and robotic surgery is the cost of special equipment and OR setting. In addition, surgeons require lengthy training and practice periods to become proficient in even one procedure performed using these endoscopic methods (Birch et al., 2007).

Surgical Attire

All members of the surgical team and all OR personnel must wear scrub attire while in the surgical suite. Scrub attire is provided by the hospital and is clean, not sterile. It is worn to reduce contamination from home and areas outside of the surgical setting. Basic surgical attire is a shirt and pants, a cap or hood (Fig. 17-6), and shoe coverings. Staff change into clean surgical attire in the OR suite locker rooms, not at home (AORN, 2010o). All members of the surgical team must cover their hair, including any facial hair.

Surgical Scrub

The surgeon, all assistants, and the scrub nurse perform a surgical scrub after putting on a mask and before putting on the sterile gown and gloves (Fig. 17-7). The scrub does not make the hands and forearms sterile. When the scrub is performed correctly, it reduces the number of organisms from the hands, arms, and nails. Rings, watches, and bracelets are removed before scrubbing because they may harbor organisms. Fingernails are kept short, clean, and healthy. Artificial nails are not worn because they too can harbor organisms.

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Anesthesia

• Type and duration of the procedure

• Area of the body having surgery

• Safety issues to reduce injury, such as airway management

• Whether the procedure is an emergency

• Options for management of pain after surgery

• How long it has been since the patient ate, had any liquids, or had any drugs

• Patient position needed for the surgical procedure

• Whether the patient must be alert enough to follow instructions during surgery

• The patient’s previous responses and reactions to anesthesia

The physical status of a patient is ranked according to a classification system developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). The anesthesiologist assesses the patient and assigns him or her to one of six categories based on current health and the presence of diseases and disorders. The categories rank patients in a range from a totally healthy patient (P1 ranking) to a patient who is brain dead (P6 ranking) (Johnson, 2011). This system is used to estimate potential risks during surgery and patient outcomes.

Anesthesia delivery begins with selecting and giving preoperative drugs (see Chapter 16). The nurse must know the actions of commonly used drugs and their effects during and after surgery. Anesthetic agents affect many systems and can worsen other health problems, increasing the patient’s need for care. For example, most anesthetics are metabolized by the liver and excreted by the kidneys. Liver or kidney impairment increases anesthetic effects and the risk for toxicity. In addition, interactions may occur between the anesthetics and other drugs the patient has received.

Anesthesia can be induced in many ways (Table 17-1). The most common forms of anesthesia used in North America include general, regional, and local anesthesia. Hypnosis or hypnoanesthesia (which induces a passive, trancelike state), cryothermia (use of cold [e.g., ice] to reduce the surface temperature of the surgical site), and acupuncture are used less often.

TABLE 17-1 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF VARIOUS TYPES OF ANESTHESIA

| TYPE | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| General | ||

| Inhalation | ||

| Intravenous | Must be metabolized and excreted from the body for complete reversal Contraindicated in presence of liver or kidney disease Increased cardiac and respiratory depression Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |