Ronald L. Hickman

Care of Critically Ill Patients with Respiratory Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

12 Coordinate nursing care for the patient being mechanically ventilated.

13 Maintain a patent airway on anyone who has experienced chest trauma.

14 Schedule essential patient care and diagnostic activities to promote rest and sleep.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Endotracheal Intubation

Animation: Pulmonary Embolism

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Clip: Stridor

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

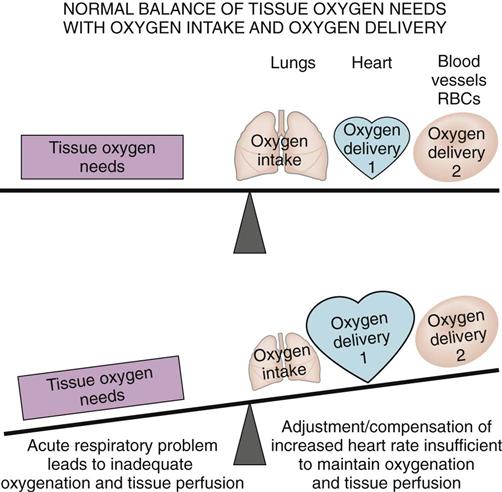

Respiratory problems can progress to an emergency and death, even with prompt treatment. These problems interfere with oxygenation and tissue perfusion and may overwhelm the adaptive responses of the cardiac and blood oxygen delivery systems (Fig. 34-1). Thus prompt recognition and interventions are needed to prevent serious complications and death.

An acute injury or problem that results in severe respiratory impairment can occur at any age. Older adults, however, are more at risk for developing critical respiratory problems. The patient who is short of breath is also anxious and fearful. Be prepared to manage both the physical and emotional needs of the patient during any respiratory emergency.

Pulmonary Embolism

Pathophysiology

A pulmonary embolism (PE) is a collection of particulate matter (solids, liquids, or air) that enters venous circulation and lodges in the pulmonary vessels. Large emboli obstruct pulmonary blood flow, leading to reduced oxygenation, pulmonary tissue hypoxia, and potential death. Any substance can cause an embolism, but a blood clot is the most common (McCance et al., 2010). PE is common, especially among hospitalized patients, and many die within 1 hour of the onset of symptoms or before the diagnosis has even been suspected (Farley et al., 2009).

Most often, a PE occurs when a blood clot from a venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in a vein in the legs or the pelvis, breaks off and travels through the vena cava into the right side of the heart. The clot then lodges in the pulmonary artery or within one or more of its branches. Platelets collect on the embolus, triggering the release of substances that cause blood vessel constriction. Widespread pulmonary vessel constriction and pulmonary hypertension impair gas exchange. Deoxygenated blood is moved into the arterial circulation, causing hypoxemia (low arterial blood oxygen level), although some patients with PE do not have hypoxemia.

Major risk factors for VTE leading to PE are:

In addition, smoking, pregnancy, estrogen therapy, heart failure, stroke, cancer (particularly lung or prostate), Trousseau’s syndrome, and trauma increase the risk for VTE and PE (Gay, 2010).

Fat, oil, air, tumor cells, amniotic fluid, foreign objects (e.g., broken IV catheters), injected particles, and infected clots or pus can enter a vein and cause PE. Fat emboli from fracture of a long bone and oil emboli from diagnostic procedures do not impede blood flow in the lungs; instead, they cause blood vessel injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Powers & Talbot, 2011). Amniotic fluid embolus occurs in women as a rare complication of childbirth, abortion, or amniocentesis. Septic clots often arise from a pelvic abscess, an infected IV catheter, and injections of illegal drugs. The effects of sepsis are more serious than the venous blockage.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Although pulmonary embolism (PE) can occur in healthy people and may give no warning, it occurs more often in some situations. Thus prevention of conditions that lead to PE is a major nursing concern. Preventive actions for PE are those that also prevent venous stasis and VTE. Best nursing practices for PE prevention are outlined in Chart 34-1. Also see Chapter 16 for more information about core measures for VTE prevention.

Lifestyle changes can help reduce the risk for PE. Urge patients to stop smoking cigarettes, especially women who take oral contraceptives. Reducing weight and becoming more physically active, such as walking one or more miles each day, can reduce risk for PE. Teach patients who are traveling for long periods to drink plenty of water, change positions often, avoid crossing the legs, and get up from the sitting position at least 5 minutes out of every hour.

For patients known to be at risk for PE, small doses of heparin, low molecular weight heparin, or a similar drug may be prescribed every 8 to 12 hours. Heparin prevents excessive clotting in patients after trauma or surgery or when restricted to bedrest. Occasionally, an antiplatelet drug such as clopidogrel (Plavix) is used in place of heparin.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Assess any patient with sudden onset of breathing difficulty for the risk factors of PE, such as previous VTE, recent surgery, or immobility (Farley et al., 2009; Winkelman, 2009).

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Respiratory manifestations are outlined in Chart 34-2. Assess the patient for difficulty breathing (dyspnea) occurring with a rapid heart rate and pleuritic chest pain (sharp, stabbing-type pain on inspiration). Other symptoms vary depending on the size and the type of embolism. Breath sounds may be normal, but crackles usually occur. Often a dry cough is present. Hemoptysis (bloody sputum) may result from pulmonary infarction.

Cardiac manifestations include tachycardiac, distended neck veins, syncope (fainting or loss of consciousness), cyanosis, and hypotension. Systemic hypotension results from acute pulmonary hypertension and reduced forward blood flow. Abnormal heart sounds, such as an S3 or S4, may occur. Electrocardiogram (ECG) findings are abnormal, nonspecific, and transient. T-wave and ST-segment changes occur in many patients; left-axis or right-axis deviations are also common.

Miscellaneous manifestations include a low-grade fever and petechiae on the skin over the chest and in the axillae. It is important to remember that many patients with PE do not have the “classic” manifestations but instead have vague symptoms resembling the flu, such as nausea, vomiting, and general malaise (Bahloul et al., 2010).

Psychosocial Assessment

Symptom onset of PE often is abrupt, and the patient is anxious. Hypoxemia may stimulate a sense of impending doom and cause increased restlessness. The life-threatening nature of PE and admission to an intensive care unit increase the patient’s anxiety and fear.

Laboratory Assessment

The hyperventilation triggered by hypoxia and pain first leads to respiratory alkalosis, indicated by low partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) values on arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. The PaO2-FiO2 (fraction of inspired oxygen) ratio falls as a result of “shunting” of blood from the right side of the heart to the left without picking up oxygen from the lungs. Shunting causes the PaCO2 level to rise, resulting in respiratory acidosis (McCance et al., 2010). Later, metabolic acidosis results from buildup of lactic acid due to tissue hypoxia. (See Chapter 14 for a discussion.)

Even if ABG studies and pulse oximetry show hypoxemia, these results alone are not sufficient for the diagnosis of PE (Bahloul et al., 2010; McCance et al., 2010). A patient with a small embolus may not be hypoxemic, and PE is not the only cause of hypoxemia.

Imaging Assessment

A chest x-ray may show a PE if it is large. Some lung infiltration may be present around the embolism site. However, the chest x-ray may not show any acute changes. Computed tomography (CT) scans are most often used to diagnose PE. A newer diagnostic method is high-resolution multidetector computer tomographic angiography (MDCTA), which is very specific but is not available at all acute care settings.

The physician may perform a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) (see Chapter 35) to help detect PE. Doppler ultrasound studies or impedance plethysmography (IPG) may be used to document the presence of VTE and to support a diagnosis of PE.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with PE are:

Planning and Implementation

Managing Hypoxemia

When a patient has a sudden onset of dyspnea and chest pain, immediately notify the Rapid Response Team. Reassure the patient, and elevate the head of the bed. Prepare for oxygen therapy and blood gas analysis while continuing to monitor and assess for other changes.

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with PE is expected to have adequate tissue perfusion in all major organs. Indicators of adequate perfusion are:

Interventions.

Nonsurgical management of PE is most common. In some cases, surgery also may be needed. Best nursing care practices for the patient with PE are listed in Chart 34-3.

Nonsurgical Management.

Management activities for PE focus on increasing gas exchange, improving lung perfusion, reducing risk for further clot formation, and preventing complications. Priority nursing interventions include implementing oxygen therapy, administering anticoagulation or fibrinolytic therapy, monitoring the patient’s responses to the interventions, and providing psychosocial support.

Oxygen therapy is critical for the patient with PE. The severely hypoxemic patient may need mechanical ventilation and close monitoring with ABG studies. In less severe cases, oxygen may be applied by nasal cannula or mask. Use pulse oximetry to monitor oxygen saturation and hypoxemia.

Monitor the patient continually for any changes in status. Check vital signs, lung sounds, and cardiac and respiratory status at least every 1 to 2 hours. Document increasing dyspnea, dysrhythmias, distended neck veins, and pedal or sacral edema. Assess for crackles and other abnormal lung sounds along with cyanosis of the lips, conjunctiva, oral mucosa, and nail beds.

Drug therapy with anticoagulants may be prescribed to prevent embolus enlargement and to prevent new clots from forming. Active bleeding, stroke, and recent trauma are reasons to avoid this therapy. Each patient is evaluated to determine the risk versus the benefit of anticoagulant therapy.

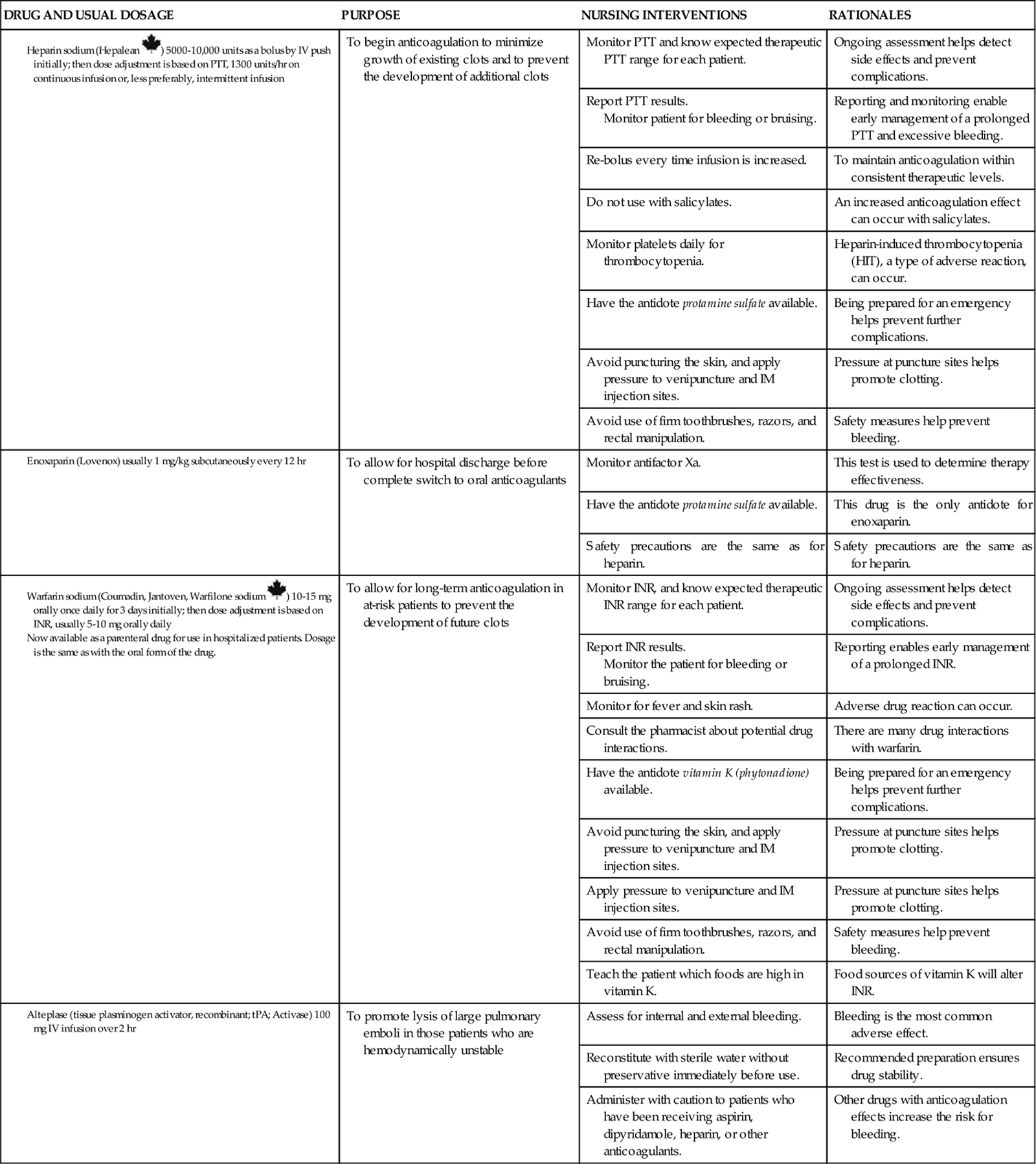

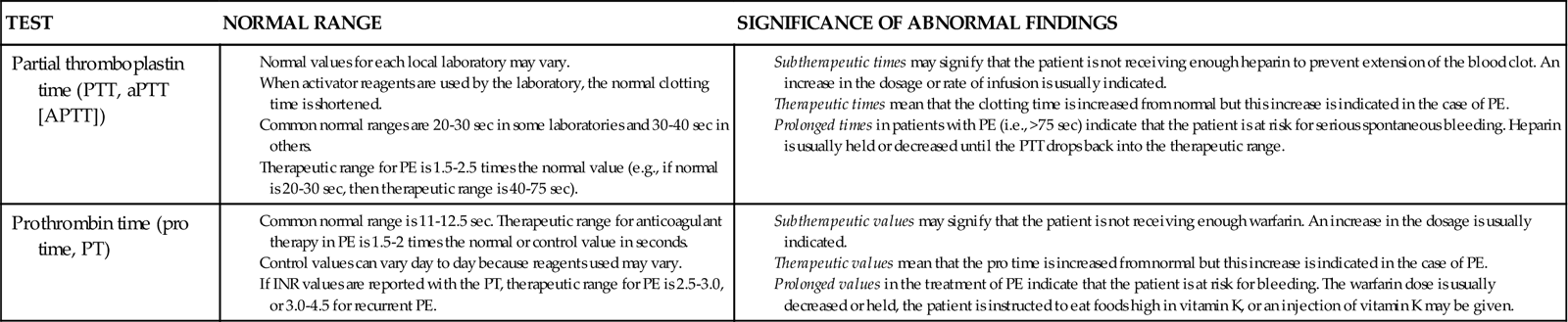

Heparin is usually used unless the PE is massive or occurs with hemodynamic instability. A fibrinolytic drug may then be used to break up the existing clot. Review the patient’s partial thromboplastin time (PTT)—also called activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)—before therapy is started, every 4 hours when therapy begins, and daily thereafter. Therapeutic PTT values usually range between 1.5 and 2.5 times the control value for this health problem.

Fibrinolytic drugs, such as alteplase (Activase, tPA), are used for PE when specific criteria are met. These include massive PE (obstructing blood flow to a lobe or more than one segment) and hemodynamic instability in which blood pressure cannot be maintained without supportive measures.

Both heparin and fibrinolytic drugs are high alert drugs. These drugs have a high risk to cause harm if given at too high a dose, too low a dose, or to the wrong patient.

Heparin therapy usually continues for 5 to 10 days. Most patients are started on an oral anticoagulant, such as warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven, Warfilone ![]() ), on the third day of heparin use. Therapy with both heparin and warfarin continues until the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches 2.0 to 3.0. A low–molecular-weight heparin (e.g., dalteparin or enoxaparin) is often used with the warfarin. Monitor the INR daily. Warfarin use continues for 3 to 6 weeks, but some patients may take warfarin indefinitely. Charts 34-4 and 34-5 list common drugs used and the laboratory tests to monitor. These drugs and the associated nursing care are discussed in Chapters 38, 40, and 41.

), on the third day of heparin use. Therapy with both heparin and warfarin continues until the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches 2.0 to 3.0. A low–molecular-weight heparin (e.g., dalteparin or enoxaparin) is often used with the warfarin. Monitor the INR daily. Warfarin use continues for 3 to 6 weeks, but some patients may take warfarin indefinitely. Charts 34-4 and 34-5 list common drugs used and the laboratory tests to monitor. These drugs and the associated nursing care are discussed in Chapters 38, 40, and 41.

Anticoagulation and fibrinolytic therapy can lead to excessive bleeding. Also, even when clotting times are in the target ranges, other problems may develop that require invasive therapy and a return to normal coagulation responses. The antidote for heparin is protamine sulfate; the antidote for warfarin is injectable phytonadione, vitamin K1 (AquaMEPHYTON, Mephyton). Antidotes for fibrinolytic therapy include clotting factors, fresh frozen plasma, and aminocaproic acid (Amicar).

Surgical Management.

Two surgical procedures for the management of PE are embolectomy and inferior vena cava filtration.

Embolectomy is the surgical removal of the embolus from pulmonary blood vessels. It may be performed when fibrinolytic therapy cannot be used for a patient who has massive or multiple large pulmonary emboli with shock. Special thrombectomy catheters that mechanically break up clots, such as the AngioJet, allow effective reduction of clots with or without the use of thrombolytic drugs. Earlier use of embolectomy for PE is being evaluated (Le & Dewan, 2009).

Inferior vena cava filtration with placement of a vena cava filter is a lifesaving measure by preventing further embolus formation for some patients. Some filters are removable, allowing filter placement before symptoms develop in patients who are at high risk for clots. These filters can be removed when the risk for clot formation decreases, or they can be left in place permanently. Patients for whom filter placement is considered less risky than drug therapy include those with recurrent or major bleeding while receiving anticoagulants, those with septic PE, and those undergoing pulmonary embolectomy. Placement of a vena cava filter is detailed in Chapter 38.

Managing Hypotension

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with PE is expected to have adequate circulation. Indicators of adequate circulation are:

Interventions.

In addition to the interventions used for hypoxemia, IV fluid therapy and drug therapy are used to increase cardiac output and maintain blood pressure.

IV fluid therapy involves giving crystalloid solutions to restore plasma volume and prevent shock (see Chapter 39). Continuously monitor the ECG and pulmonary artery and central venous/right atrial pressures of the patient receiving IV fluids because increased fluids can worsen pulmonary hypertension and lead to right-sided heart failure. Also monitor indicators of fluid adequacy, including urine output, skin turgor, and moisture of mucous membranes.

Drug therapy with agents that increase myocardial contractility (positive inotropic agents) may be prescribed when IV therapy alone does not improve cardiac output. Common drugs include milrinone (Primacor) and dobutamine (Dobutrex). Assess the patient’s cardiac status hourly during therapy with inotropic drugs. Vasodilators, such as nitroprusside (Nipride, Nitropress), may be used to decrease pulmonary artery pressure if it is impeding cardiac contractility.

Minimizing Bleeding

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with PE is expected to remain free from bleeding. Indicators are:

Interventions.

As a result of drug therapy that disrupts clots or prevents their formation, the patient’s ability to start and continue the blood-clotting cascade when injured is impaired, increasing the risk for bleeding. Priority nursing actions are ensuring that appropriate antidotes are present on the nursing unit, protecting the patient from situations that could lead to bleeding, and monitoring closely the amount of bleeding that is occurring.

Assess at least every 2 hours for evidence of bleeding (e.g., oozing, bruises that cluster, petechiae, or purpura). Examine all stools, urine, drainage, and vomitus for gross blood, and test for occult blood. Measure any blood loss as accurately as possible. Measure the patient’s abdominal girth every 8 hours (increasing girth can indicate internal bleeding). Best practices to prevent bleeding are listed in Chart 34-6.

Monitor laboratory values daily. Review the complete blood count (CBC) results to determine the risk for bleeding and whether actual blood loss has occurred. If the patient has severe blood loss, packed red blood cells may be prescribed (see Transfusion Therapy in Chapter 42). Monitor the platelet count. A decreasing count may indicate ongoing clotting or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) caused by the formation of anti-heparin antibodies.

Minimizing Anxiety

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with PE is expected to have anxiety reduced to an acceptable level. Indicators include that he or she consistently demonstrates these behaviors:

Interventions.

The patient with PE is anxious and fearful for many reasons, including the presence of pain. Interventions for reducing anxiety in those with PE include oxygen therapy (see Interventions discussion on pp. 664-667 in the Managing Hypoxemia section), communication, and drug therapy.

Communication is critical in allaying anxiety. Acknowledge the anxiety and the patient’s perception of a life-threatening situation. Stay with him or her, and speak calmly and clearly, providing assurance that appropriate measures are being taken. When giving drugs, changing position, taking vital signs, or assessing the patient, explain the rationale and share information.

Drug therapy with an antianxiety drug may be prescribed if the patient’s anxiety increases or prevents adequate rest. Unless he or she is mechanically ventilated, sedating agents are avoided to reduce the risk for hypoventilation. When pain is present, pharmacologic therapy is used for pain management. Care is taken to avoid suppressing the respiratory response.

Community-Based Care

The patient with a PE is discharged when hypoxemia and hemodynamic instability are resolved and adequate anticoagulation has been achieved. Anticoagulation therapy usually continues after discharge.

Home Care Management

Some patients are discharged to home with minimal risk for recurrence and no permanent physiologic changes. Others have heart or lung damage that requires home and lifestyle modification.

Patients with extensive lung damage may have activity intolerance and become fatigued easily. The living arrangements may need to be modified so that patients can spend all or most of the time on one floor and avoid climbing stairs. Depending on the degree of impairment, patients may require some or much assistance with ADLs.

Teaching for Self-Management

The patient with a PE may continue anticoagulation therapy for weeks, months, or years after discharge, depending on the risks for PE. Teach him or her and the family about Bleeding Precautions, activities to reduce the risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and recurrence of PE, complications, and the need for follow-up care (Chart 34-7).

Health Care Resources

Patients using anticoagulation therapy are usually seen in a clinic or health care provider’s office weekly for blood drawing and assessment. Those who are homebound may have a home care nurse perform these actions (see Chart 34-8 for a focused assessment guide). Patients with severe dyspnea may need home oxygen therapy. Respiratory therapy treatments can be performed in the home. The nurse or case manager coordinates arrangements for oxygen and other respiratory therapy equipment to be available if needed at home.

Evaluation: Outcomes

Evaluate the care of the patient with PE on the basis of the identified priority patient problems. The expected outcomes are that he or she:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree