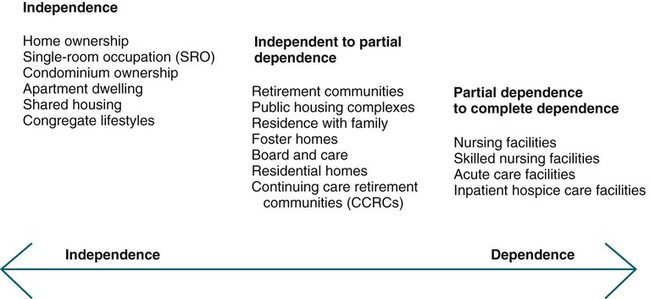

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Compare the major features, advantages, and disadvantages of several residential options available to the older adult. 2. Assist older adults and their families in making an informed choice when relocation to a more protected setting becomes necessary. 3. Describe factors influencing the provision of long-term care. 4. Identify interventions to improve care for older adults in acute and long-term care settings. 5. Discuss interventions to improve transitions of care and outcomes for older adults moving between health care settings. “Home” provides basic shelter, is a place to establish security, and is the place where one “belongs.” It should provide the highest possible level of independence, function, and comfort. Most older people prefer to remain in their own homes and “age-in-place,” rather than relocate, particularly to institutional living. The ability to age in place depends on appropriate support for changing needs so the older person can stay where he or she wants. Developing elder-friendly communities and increasing opportunities to “age in place” can enhance the health and well-being of older people (Chapter 13). Some older people, by choice or by need, move from one type of residence to another. A number of options exist, especially for those with the financial resources that allow them to have a choice. Residential options range along a continuum from remaining in one’s own home; to senior retirement communities; to shared housing with family members, friends, or others; to residential care communities such as assisted living settings; to nursing facilities for those with the most needs, (Figure 16-1). There are many different models of senior housing, and older people may seek assistance from nurses in choosing what kind of living situation will be best for them. It is important to be aware of the various options available in your local community as well as the advantages, disadvantages, cost, and services provided in each option. When discharging older people from the hospital, knowledge of where they live or the type of setting to which they are being discharged, will assist in individualizing teaching so that outcomes can be enhanced for both the older adult and his or her family. Another model of shared housing is that of opening one’s personal home to others. Older people often live in houses, which were purchased in their young adult years, and find that as they age, much of the space may be underused. Sharing a house can be easily implemented by locating, screening, and matching older people looking for houses to share with those who have them. The National Shared Housing Resource Center (NSHRC) (http://www.nationalsharedhousing.org/) has established subgroups nationally to assist individuals interested in home sharing. Those who have done so report feeling safer and less lonely. Studies on home sharing focus on the effects on well-being, finances, health, social life, and daily satisfaction. PACE is now recognized as a permanent provider under Medicare and a state option under Medicaid. In 2009, there were 72 PACE programs operational in 30 states. PACE has been approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as an evidence-based model of care. Models such as PACE are innovative care delivery models, and continued development of such models are important as the population ages. More information about PACE models and outcomes of care can be found at www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/10_PACE.asp and at http://www.npaonline.org/website/article.asp?id=12. Adult day services (ADS) are community-based group programs designed to provide social and some health services to adults who need supervised care in a safe setting during the day. They also offer caregivers respite from the responsibilities of caregiving, and most provide educational programs for caregivers and support groups. There are more than 4,600 adult day services centers across the United States—a 35% increase since 2002. Adult day centers are serving populations with higher levels of physical disability and chronic disease, and the number of older people receiving adult day services has increased 63% over the last eight years (National Adult Day Services Association, Ohio State University College of Social Work, MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2009). The average ADS cost/day is $66.71. Some ADS are private pay, and others are funded through Medicaid home and community-based waiver programs, state and local funding, and the Veteran’s Administration. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provides additional funding to states for home and community-based care. Pilot programs have been implemented through Medicare and are being evaluated. ADS hold the potential to meet the need for cost-efficient and high-quality long-term care services, and continued expansion and funding is expected. Local area agencies on aging are good sources of information about adult day services and other community-based options (National Adult Day Services Association, Ohio State University College of Social Work, MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2009). Residential care facilities are the fastest growing housing option available for older adults in the United States. This kind of facility is viewed as more cost effective than nursing homes while providing more privacy and a homelike environment. Medicare does not cover the cost of care in these types of facilities. In some states, costs may be covered by private and long-term care insurance and some other types of assistance programs. Assisted living is primarily private pay, although 41 states currently have a Medicaid Waiver/Medicaid State Plan for a limited amount of residents (AAHSA, 2011). The rates charged and what services those rates include vary considerably, as do regulations and licensing. A popular type of residential care can be found in assisted living facilities (ALFs), also called board and care homes or adult congregate living facilities (ACLFs). Assisted living is a residential long-term care choice for older adults who need more than an independent living environment but do not need the 24 hours/day skilled nursing care and the constant monitoring of a skilled nursing facility. The typical assisted living resident is an 86-year-old woman who is mobile but needs assistance with 2 ADLs (Box 16-1). Assisted living is more expensive than independent living and less costly than skilled nursing home care, but it is not inexpensive. There are 39,500 assisted living facilities in the United States. Costs vary by geographical region, size of the unit, and relative luxury. The average base rate (room and board and limited other services) in an assisted facility is $2,930 monthly, or $35,160 annually in 2010 (Prudential Life Insurance Company of America, 2011). Most ALFs offer two or three meals per day, light weekly housekeeping, and laundry services, as well as optional social activities. Each added service increases the cost of the setting but also allows for individuals with resources to remain in the setting longer, as functional abilities decline. With the growing numbers of older adults with dementia residing in ALFs, many are establishing dementia-specific units. It is important to investigate services available as well as staff training when making decisions as to the most appropriate placement for older adults with dementia. Continued research is needed on best care practices as well as outcomes of care for people with dementia in both ALFs and nursing homes. The Alzheimer’s Association has issued a set of dementia care practices for ALFs and nursing homes (Alzheimer’s Association, 2009) (http://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_DCPRphases1n2.pdf) and an evidence-based guideline, Dementia Care Practice Recommendations for Assisted Living Residences and Nursing Homes (Tilly & Reed, 2006) (www.guideline.gov) is also avaliable. The American Assisted Living Nurses Association has established a certification mechanism for nurses working in these facilities and has also developed a Scope and Standards of Assisted Living Nursing Practice for Registered Nurses (www.alnursing.org). Advanced practice gerontological nurses are well suited to the role of primary care provider in ALFs, and many have assumed this role. Consumers are advised to inquire as to exactly what services will be provided and by whom if an ALF resident becomes more frail and needs more intensive care. The Assisted Living Federation of America (2010) provides a consumer guide for choosing an assisted living residence (http://www.alfa.org/images/alfa/PDFs/getfile.cfm_product_id=94&file=ALFAchecklist.pdf ). Life care communities, also known as continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs), provide the full range of residential options, from single-family homes to skilled nursing facilities all in one location. Most of these communities provide access to these levels of care for a community member’s entire remaining lifetime, and for the right price, the range of services may be guaranteed. Having all levels of care in one location allows community members to make the transition between levels without life-disrupting moves. For married couples in which one spouse needs more care than the other, life care communities allow them to live nearby in a different part of the same community. This industry is maturing, and there are 1900 CCRCs in the United States, housing more than 745,000 older adults (AAHSA, 2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) seniors face several problems in housing in their older years. They may have little family support and may face discrimination in housing options. Many LGBT seniors say they do not feel welcome at traditional residential options. Those who wish to live together are discouraged from doing so by some organizations. Residential facilities and communities designed specifically for LGBT seniors are increasing in number across the country. Nurses should be aware of this heretofore invisible group of older adults who need access to welcoming resources. Chapters 21 and 22 discusses issues specific to LGBT seniors in more depth. Although the costs of the majority of senior communities are borne by the consumers, for elders with limited incomes, federally subsidized rental options are available in some areas of the country. Older adults benefiting from this option are assisted through rental housing subsidized by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Although not all HUD housing is designated for senior living, Section 202 of the Housing Act, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, approved the construction of low-rent units especially for elders. These units may also have provisions for health care, recreation, and transportation. Under Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1983, tenants locate their own unit. Usually the tenant pays 30% of his or her adjusted gross income toward the rent, and HUD assists with supplementary vouchers to meet the fair market value of the rental (American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging [AAHSA], 2011). Older adults often enter the health care system with admissions to acute care settings. The admission rate for older adults is as high as three times those of younger individuals (Resnick, 2009). Exacerbations of chronic illnesses and injuries are often the cause of hospitalizations for older adults. Acutely ill older adults frequently have multiple chronic conditions and comorbidities and present many care challenges. Hospitals are dangerous places for elders: 34% experience functional decline, and iatrogenic complications occur in as many as 29% to 38%, a rate three to five times higher than in younger patients (Inouye et al, 2000; Kleinpell, 2007). Common iatrogenic complications include functional decline, pneumonia, delirium, new-onset incontinence, malnutrition, pressure ulcers, medication reactions, and falls. Nurses caring for older adults in hospitals may function in the direct care provider role, as well as in leadership and management positions. Most nurses who work in hospitals are caring for older patients, and many have not had gerontological nursing content in their basic nursing education programs. In a survey of hospital nurses, only 37% reported participating in a hospital in-service training program on care of older adults (Mezey et al., 2007). “Few of the country’s 6,000 hospitals have institutional practice guidelines, educational resources, and administrative practices that support best practices care of older adults” (Boltz et al., 2008, p. 176). As part of the Nurse Competence in Aging project, the American Association of Nurse Executives (AONE) has developed guiding principles for the elder-friendly hospital/facility (Box 16-2). Recognizing the need for models of nursing practice to prevent iatrogenesis and improve outcomes for older hospitalized patients, the Hartford Geriatric Nursing Institute developed, in 1992, the Nurses Improving Care for Health System Elders (NICHE) program. “NICHE is built on the premise that the bedside nurse plays a pivotal role in influencing the older adult’s hospital experience and outcomes, through direct nursing care, as well as coordination of interdisciplinary activities” (Resnick, 2009, p. 81). More than 300 hospitals in more than 40 states, as well as parts of Canada, are involved in NICHE projects. NICHE units of various types have been developed including the geriatric resource nurse (GRN) model and the acute care of the elderly (ACE) unit (www.nicheprogram.org). The GRN model is the most frequently implemented NICHE model. In this model, staff nurses receive competency-based training and are mentored by advanced practice nurses in care of hospitalized older adults. GRNs then function as clinical resource experts on geriatric issues to staff on their unit. Evidence-based interdisciplinary protocols, geriatric-specific resources, management strategies, policies to meet the specialized needs of older adults, as well as an online knowledge center providing educational support, are features of the NICHE model (Resnick, 2009). This is an innovative role for a hospital staff nurse interested in care of older adults. Outcomes in hospitals using NICHE models include enhanced nursing knowledge and skills related to treatment of common geriatric syndromes, patient and nurse satisfaction, decreased length of stay, reductions in admission rates, and reductions in hospital costs (Fulmer et al., 2002; Mezey et al., 2004b; Boltz et al., 2008; Steele, 2010). Further research on patient outcomes, patient and staff satisfaction, and cost of implementation of NICHE models is needed. The ACE model was originally developed at University Hospitals in Cleveland in conjunction with the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University. A 29 bed medical surgical specialty unit was renovated and dedicated as an ACE unit to prevent functional decline of targeted older adult patients. The NICHE ACE model designates a specific unit or section of a unit to deliver interventions known to improve the clinical outcomes of older adult patients. Key elements include environmental modifications for older patients and interdisciplinary staff with expertise in geriatrics and prevention of geriatric syndromes (www.nicheprogram.org/niche_models). Nurses will care for older adults in hospitals and long-term care, but the majority of older adults live in the community. Community-based care settings include home care, independent senior housing, retirement communities, residential care facilities, adult day health programs, primary care clinics, and public health departments. The growth in home- and community-based health care is expected to continue because older people prefer to age in place. Other factors influencing the growth of home-based care include rapidly escalating health care costs. The Independence at Home Act, part of the Affordable Care Act, supports home-based primary care teams, including physicians and nurse practitioners, to deliver primary care services to high-risk patients. This three-year demonstration project will receive mandatory appropriations of $5 million per year. After the project ends, the Department of Health and Human Services will evaluate the program and report to Congress (AARP, 2010; Landers, 2010). Advances in technology for remote monitoring of health status and safety, and point-of-care testing devices show promise in improving outcomes for elders who want to age in place. These technologies present exciting opportunities for nurses in the management and evaluation of care and call for increased education and practice experiences for nursing students in home-based care. Subacute care is more intensive than traditional nursing home care and several times more costly, but far less costly than care in an acute-care hospital. Skilled nursing facilities are the most frequent site of postacute care in the United States, and they treat 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries requiring postacute care following hospitalization (Alliance for Quality Nursing Home Care and the American Health Care Association, 2010). The expectation is that the patient will be discharged home or to a less intensive setting. In addition to skilled nursing care, rehabilitation services are an essential component of subacute units. Length of stay is usually less than one month and is largely reimbursed by Medicare. Patients in subacute units are usually younger and less likely to be cognitively impaired than those in traditional nursing home care. Generally, higher levels of professional staffing are found in the subacute setting than those in the traditional nursing home setting because of the acuity of the patient’s condition. Nursing homes also care for patients who may not need the intense care provided in subacute units but still need ongoing 24-hour care. This may include individuals with severe strokes, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease, and those receiving hospice care. More than 50% of residents in nursing homes are cognitively impaired, and nursing homes are increasingly caring for people at the end of life. Twenty-three percent of Americans die in nursing homes, and this figure is expected to increase 40% by 2040 (Carlson, 2007). Nursing home residents represent the most frail of all older adults. Their needs for 24-hour care could not be met in the home or residential care setting, or may have exceeded what the family was able to provide. There are approximately 16,100 certified nursing homes in the United States, and more than 1.4 million older adults reside in nursing homes. The majority of nursing homes are for-profit organizations (67%), with 31% managed by not-for-profit organizations (AAHSA, 2011). Nursing home chains own 54% of all nursing homes (Harrington et al., 2010). The number of nursing home beds is decreasing in the United States and the number of Medicaid-only beds has decreased by half since 1995 (Gleckman, 2010). This is most likely a result of the increased use of residential care facilities and more reimbursement by Medicaid programs for community-based care alternatives. With the increasing number of older people, projections are that there will be a threefold increase in the number of older people needing nursing home care by 2030. People who reach age 65 will likely have a 40% chance of entering a nursing home, and about 10% who enter a nursing home will stay there 5 years or more (Medicare.gov, 2010a). Continued attention to the development of a range of appropriate, high-quality alternatives and different models of long-term care and services is needed. Rehabilitation is a philosophy, not a place of care, or a set of specific services. In all settings, rehabilitation and restorative care is focused on maximizing the individual’s strengths and supporting limitations to assist the patient to achieve the highest practicable level of function. Rehabilitation and restorative care “seeks to improve the individual’s quality of life in any way, no matter how small, in relation to physical, emotional, or spiritual well-being; and ultimately return that individual to a residence of his choice and at minimal personal risk. This implies integration into society plus support in and by the community” (Williams, 1993, p. 361). People who are cared for in subacute units, as well as long-term units of nursing facilities, require access to rehabilitation and restorative care services that maintain or improve their function and prevent excess disability. These services are required under federal and state regulations and are integral to quality indicators in nursing facilities. Barbara Resnick, a noted gerontological nursing researcher, has published extensively on restorative care in both nursing facilities and residential care facilities (Chapters 2 and 12). Restorative nursing programs for ADLs, toileting, range of motion, ambulation, and feeding contribute to restoration and maintenance of function for nursing facility residents who may have been discharged or who are not eligible for reimbursement for rehabilitation services by physical, occupational, or speech therapists. Both rehabilitation and restorative programs require comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment and involvement of the patient and family in development of a plan of care with short and long-term goals (Box 16-3). Rehabilitation and restorative care is increasingly important in light of shortened hospital stays that may occur before conditions are stabilized and the older adult is not ready to function independently. Costs for nursing homes vary by geographical location, ownership, and amenities, but the average annual cost for a semiprivate room is $215 per day or $78,475 annually. Nursing home rates have increased more than 10% since 2008 and nearly 50% since 2004 (Prudential Insurance Company of America, 2010). The majority of the cost of care in nursing homes is borne by Medicaid (42%), followed by Medicare (25%), out of pocket (22%), and private insurance and other sources (11%) (AAHSA, 2011). Medicare covers 100% of the costs for the first 20 days. Beginning on day 21 of the nursing home stay, there is a significant co-payment. This co-payment may be covered by a Medigap policy. After 100 days the individual is responsible for all costs. In order for a nursing home stay to be covered by Medicare, you must enter a Medicare-approved “skilled nursing facility” or nursing home within 30 days of a hospital stay that lasted at least 3 days (Medicare.gov,2010). Complex medical treatments (e.g., feeding tube, tracheostomy, intravenous [IV] therapy) and rehabilitation services such as occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), or speech therapy (ST), are considered skilled care. Medicare does not cover the costs of care in chronic, custodial, and long-term units. If the older person was admitted to the nursing home because of a dementia diagnosis and the need for assistance with ADLs and maintenance of safety, Medicare would not cover the cost of care unless there was some skilled need (Chapter 20). Concern is growing nationwide about the financing of long-term care and the ability of the states and the federal government to continue to support costs through the Medicaid programs. The reimbursement levels of both Medicare and Medicaid do not cover actual costs, and there is fear that if further cuts are made, quality of care will be more drastically compromised. The increasing burden on Medicaid is unsustainable, and assuming present growth, Medicaid costs for long-term care will double by 2025 and increase fivefold by 2045 (AAHSA, 2008). The purchase of long-term care insurance is an option, but it is expensive and pays for less than 5% of long-term care costs (AAHSA, 2011). The Community Living Assistance Services and Support (CLASS), approved as part of the Patient Population and Affordable Care Act, is a voluntary, federally administered, consumer-directed, long-term insurance plan. The CLASS plan provides those who participate with cash to help pay for needed assistance if they become functionally limited, in a place they call home, from independent living to a nursing facility. Health care coverage for people with long-term care needs is a major national issue that demands attention along with the growing numbers of uninsured individuals of all ages and the rising costs of care in the United States. In response to the nation’s need for a long-term care financing solution, the AAHSA has made recommendations for a model for future financing for long-term care (www.thelongtermcareresolution.org/problem.aspx).

Care Across the Continuum

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

Residential Options in Later Life

Shared Housing

Community Care

Adult Day Services

Residential Care Facilities

Assisted Living

Continuing Care Retirement Communities

Population-Specific Communities

Senior Retirement Communities

Acute Care for Older Adults

Nursing Roles and Models of Care

Community-Based and Home-Based Care

Nursing Homes

Characteristics of Nursing Homes

Rehabilitation and Restorative Care Services

Costs of Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access