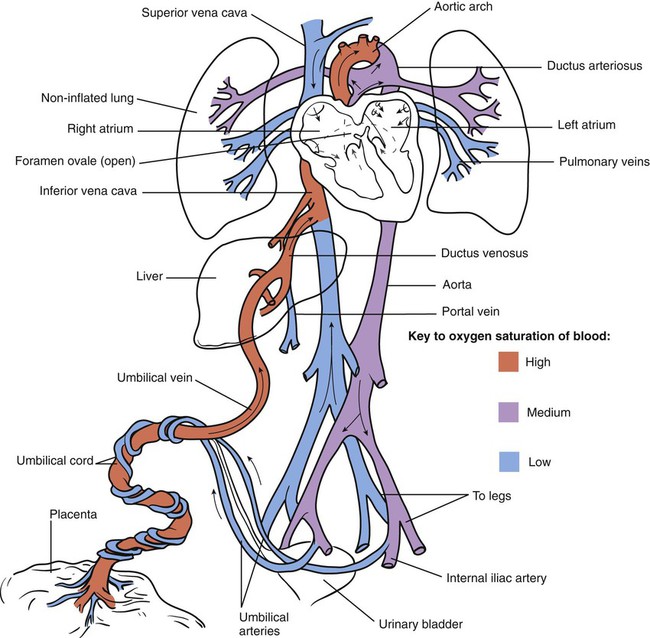

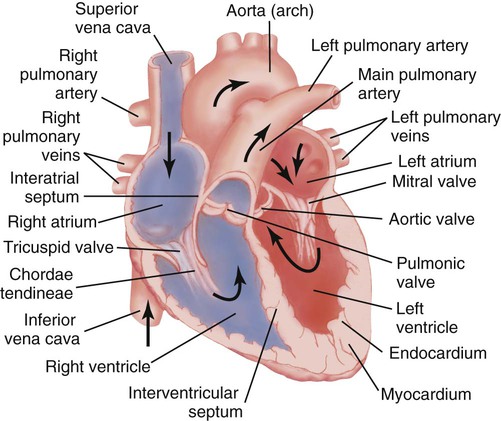

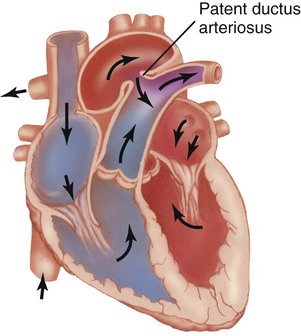

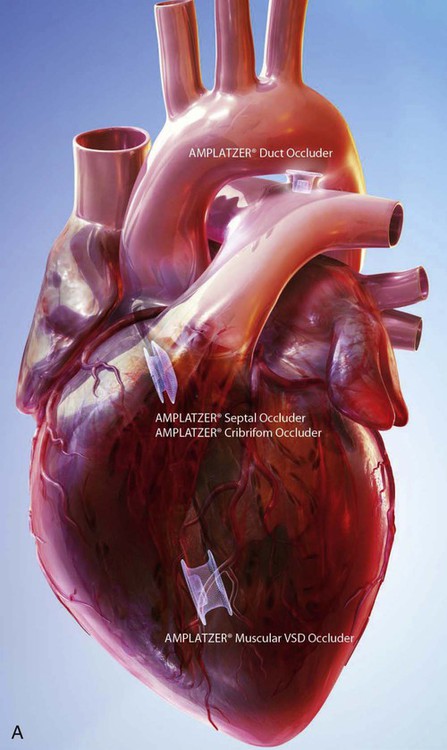

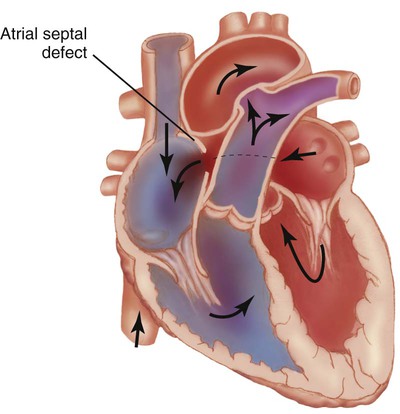

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Describe the changes from fetal to neonatal circulation 3. Summarize the symptoms of a congenital heart defect with increased pulmonary blood flow 4. Discuss the corrective interventions for a child with mixed heart defects 5. Develop a teaching plan for an older child who is scheduled for a cardiac catheterization 6. List the symptoms for an infant with CHF 7. List three major and two minor manifestations of acute rheumatic fever as determined by the modified Jones criteria 8. Identify the priority nursing care for a child with rheumatic fever Heart defects are the most common birth defect and are the leading cause of birth defect-related deaths. The incidence rate of infants born with a congenital heart defect is about one per 125 deliveries (March of Dimes, 2006). With the advancement in diagnosis and treatment, about 85% of children live into adulthood. This has created a new subspecialty, the adult with congenital heart disease. Fetal circulation differs from normal circulation as the organ of oxygenation is the placenta. Oxygenated blood from the placenta flows through the umbilical vein to the liver and inferior vena cava. A small portion of the blood supports the hepatic tissue, while the rest flows through the ductus venosus into the inferior vena cava. As blood enters the right atrium, most of the flow is directed through the foramen ovale (a septum connection between the right and left atrium) to the left side of the heart and out the aorta. The remaining blood continues to flow to the right ventricle and out the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Since the lungs are not functioning, only a small amount of the oxygenated blood is needed to provide nutrients to lung tissue. The majority of this oxygenated flow is diverted again through the ductus arteriosus (a connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta) into the aorta. The oxygenated blood is distributed to the rest of the body and is returned through the umbilical arteries to the placenta (Figure 12-1). In the past, congenital heart defects were divided into two groups: cyanotic and acyanotic. This categorization has proved inaccurate because children with acyanotic defects may develop cyanosis and those with cyanotic disease may be pink in color. Presently, defects are classified according to the effect the defect has on the movement of circulating blood. The study of blood circulation is termed hemodynamics (hemo, blood; dynamis, power). Defects can be classified as (1) defects with increased pulmonary blood flow, (2) obstructive defects, (3) defects with decreased pulmonary blood flow, and (4) mixed defects. A list of the hemodynamics and the heart defect(s) associated with each is given in Box 12-1. Several diagnostic tools can be used in evaluation of a child with CHD. Not all testing is necessary for each child. The tools include laboratory tests, electrocardiogram, Holter monitor, event recorder, chest radiography, echocardiogram, MRI, and cardiac catheterization. The diagnostic procedures listed in Box 12-2 can be used in identifying the type of heart defect. • Temperature and color of extremity below (distal) insertion site • Pulse of extremity below insertion site • Sensation of affected extremity • Vital signs every 15 minutes for first hour and then hourly • Dressing for excessive bleeding The symptoms, as indicated in Box 12-3, depend on the location and type of heart defect. Some children have mild cases and can lead a fairly normal life with medical management. Others are treated medically until the optimal time for surgery. Heart transplantation is an option in some cases. Hypoxia is a result of inadequate oxygenation and can present with cyanosis in children with heart defects. Cyanosis can be generalized or localized such as in the hands, feet, or lips or around the mouth. Cyanosis may be constant or transient and can be influenced by the child’s behavior such as crying. Crying can improve or worsen the cyanosis. Overt cyanosis can be difficult to observe in children with dark skin. For these children, cyanosis can be detected in the mucous membranes of the mouth, on the palms of the hands, or on the bottom of the feet. Chronic hypoxia can result in long-lasting pooling of the blood in the capillaries resulting in clubbing of the fingers and/or toes (Figure 12-2). The child may also present with a pale or mottled appearance. Arterial oxygen saturation can differ with each type of defect. Ideally, oxygen saturation is between 95% and 98% in normal children, and saturations below 88% can result in cyanosis. Some of the defects have saturations much lower than 88%. Assessment of the heart rate of a child with hypoxemia is important as hypoxemia can result in bradycardia. Some common nursing diagnoses associated with CHD are listed in Box 12-4. The normal heart is illustrated in Figure 12-3. Patent ductus arteriosus is one of the most common cardiac anomalies (Figure 12-4). The word patent means open. PDA occurs twice as frequently in females as in males. In the premature infant, indomethacin or ibuprofen may be administered to facilitate closure of the ductus (Sadowski, 2009). If drug treatment is not successful, other nonsurgical intervention may be tried. Recent interventional devices such as coils or the Amplatzer PDA device (Figure 12-5) have provided closure for small ducts during cardiac catheterization. Occluder device risks include leaking and occlusions (Park, 2008). For large ducts, surgical repair includes ligation of the ductus through a left thoracotomy or with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). If this condition is left uncorrected, the child eventually could develop CHF or endocarditis. The prognosis for a corrected PDA is excellent. Atrial septal defect (ASD) is one of the more common congenital heart anomalies (Figure 12-6). The incidence is higher in females than in males. There is an abnormal opening between the right and left atria. Blood that contains oxygen is forced from the left atrium to the right atrium. This type of arteriovenous shunt does not produce cyanosis unless the blood flow is reversed by heart failure. Most children do not have symptoms, but CHF and failure to thrive may be present in those with large openings. Currently, the defect can be repaired either with open heart surgery or percutaneous occluder devices (e.g., the Amplatzer ASD; see Figure 12-5) during cardiac catheterization. Open heart surgery requires the child being placed on the heart-lung machine during the procedure and has all the risks of a surgical procedure. Occluder devices can be used with openings located in certain places along the septum and openings with a small diameter. The occluder devices require shorter hospital stays. The child may require antimicrobial prophylaxis for potential infective endocarditis, and low-dose aspirin or an antiplatelet such as Plavix for clot prevention (Ferri, 2011). Both surgical and nonsurgical procedures have good results.

Cardiac Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

Cardiovascular System

Congenital Heart Disease

Classification

Diagnostic Tools

Signs and Symptoms

Defects with Increased Pulmonary Blood Flow

Patent Ductus Arteriosus.

Atrial Septal Defect.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cardiac Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access