Chapter 23 Cancer Development

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Help people identify behaviors that reduce the risk for cancer development and cancer death.

2. Teach the recommended screening practices and schedules for specific cancer types.

3. Explain why causes of specific cancers can be hard to establish.

4. Use knowledge of basic biology to understand how normal cells can become malignant.

5. Distinguish the features of normal cells from those of benign tumors and cancer cells.

6. Discuss the roles of oncogenes and suppressor genes in cancer development.

7. Compare the cancer development processes of initiation and promotion.

8. Interpret cancer grading, ploidy, and staging reports.

9. Explain how cancer metastasis occurs and the common sites of distant metastasis.

10. Discuss the role of immunity in protection against cancer.

11. Assess the individual patient’s need for genetic testing for cancer predisposition based on family history.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Metastatic Spread of Breast Cancer

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Most common types of altered cell growth, such as moles or skin tags, are benign (harmless) and do not require intervention. Malignant cell growth, or cancer, however, is serious and, without intervention, leads to death. Cancer is a common health problem in the United States and Canada. Nearly 1.5 million people are newly diagnosed with cancer each year (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011; Canadian Cancer Society, 2010). Some types of cancer can be prevented; others have better cure rates if diagnosed early. As a nurse, you can have a vital impact in educating the public about cancer prevention and early detection methods.

Cancer will occur in about 1 of every 3 people currently living in North America (ACS, 2011; Canadian Cancer Society, 2010), although cancer risk differs for each person. More than 10 million Americans with a history of cancer are alive today, nearly 5 million of whom are considered cured (ACS, 2011).

Pathophysiology

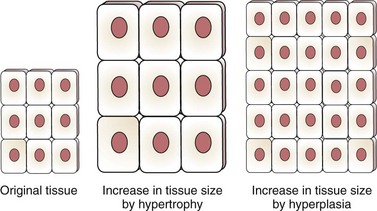

Some tissues and organs stop growing by cell division after development is complete. For example, heart muscle cells no longer divide after fetal life; the number of heart muscle cells is fixed at birth. The size of the heart increases as the person grows because each cell gets larger, but the number of heart muscle cells does not increase. Growth that causes tissue to increase in size by enlarging each cell is hypertrophy. Growth that causes tissue to increase in size by increasing the number of cells is hyperplasia (Fig. 23-1).

Biology of Normal Cells

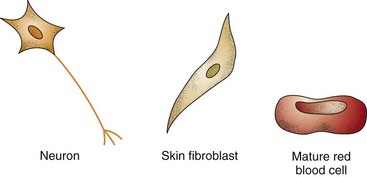

Specific morphology is the feature in which each normal cell type has a distinct and recognizable appearance, size, and shape, as shown in Fig. 23-2.

A small nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio means that the nucleus of a normal cell does not take up much space inside the cell. As shown in Fig. 23-2, the size of the normal cell nucleus is small compared with the size of the rest of the cell, including the cytoplasm.

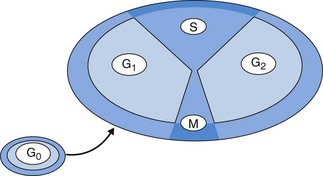

Orderly and well-regulated growth is a very important feature of normal cells. They divide (undergo mitosis) for only two reasons: (1) to develop normal tissue or (2) to replace lost or damaged normal tissue. Even when they are capable of mitosis, normal cells divide only when body conditions, including the need for more cells, adequate space, and sufficient nutrients and other resources, are just right. Cell division (mitosis), occurring in a well-recognized pattern, is described by the cell cycle. Fig. 23-3 shows the phases of the cell cycle. The amount of time needed for one cell to divide completely into two cells is the generation time. For normal cells, the generation time varies by tissue and organ type.

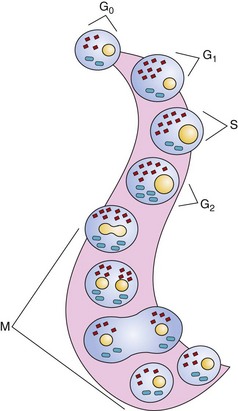

Fig. 23-4 shows the activities of the phases of the cell cycle (described below):

• G1. In this phase, the cell is getting ready for division by taking on extra nutrients, making more energy, and growing extra membrane. The amount of cytoplasm also increases.

• S. Because making one cell into two cells requires twice as much of everything, including DNA, the cell must double its DNA content through DNA synthesis. This process occurs in S phase.

• G2. In this phase, the cell makes important proteins that will be used in actual cell division and in normal physiologic function after cell division is complete.

• M. The single cell splits apart into two cells (actual mitosis) during M phase.

Apoptosis is programmed cell death. Not only do normal cells have to divide only when needed and perform their specific differentiated functions, some cells also have to die at the appropriate time to ensure optimum body function. Thus normal cells have a finite life span. With each round of cell division, the telomeric DNA at the ends of the cell’s chromosomes shortens (see Chapter 6). When this DNA is gone, the cell responds to signals for apoptosis. The purpose of apoptosis is to ensure that each organ has an adequate number of cells at their functional peak.

Biology of Abnormal Cells

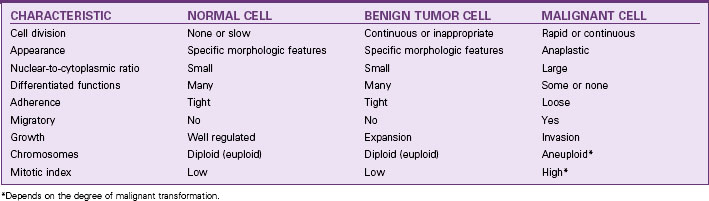

Body cells are exposed to a variety of conditions that can alter how the cells grow or function. When either cell growth or cell function is changed, the cells are considered abnormal. Table 23-1 compares features of normal, benign tumor, and cancer (malignant) cells.

Features of Benign Tumor Cells

• Specific morphology occurs with benign tumors. They look like the tissues they come from, retaining the specific morphology of parent cells.

• A small nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is a feature of benign tumors just like completely normal cells.

• Specific differentiated functions continue to be performed by benign tumors. For example, in endometriosis, a type of benign tumor, the normal lining of the uterus (endometrium) grows in an abnormal place (e.g., on an ovary, on the peritoneum, or in the chest cavity). This displaced endometrium acts just like normal endometrium by changing each month under the influence of estrogen. When the hormone level drops and the normal endometrium sheds from the uterus, the displaced endometrium, wherever it is, also sheds.

• Tight adherence of benign tumor cells to each other occurs because they continue to make fibronectin. In addition, many benign tissues are “encapsulated,” or surrounded with fibrous connective tissue, helping to hold the benign tissue together.

• No migration or wandering of benign tissues occurs because they remain tightly bound and do not invade other body tissues.

• Orderly growth with normal growth patterns occurs in benign tumor cells even though their growth is not needed. Growth may continue beyond an appropriate time or occur in the wrong place, but the rate of growth is normal. The benign tumor grows by hyperplastic expansion. It does not invade.

• Normal chromosomes are usually found in benign tumor cells, although there are exceptions. Most of these cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes, the correct number for humans.

Features of Cancer Cells

• Anaplasia is the cancer cells’ loss of the specific appearance of their parent cells. As a cancer cell becomes more malignant, it becomes smaller and rounded. This appearance change can make diagnosis of cancer type difficult, because many different types of cancer cells look alike.

• A large nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio occurs in cancer cells with the cancer cell nucleus being larger than that of a normal cell and the cancer cell being small. The nucleus occupies much of the space within the cancer cell, creating a large nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio.

• Specific functions are lost partially or completely in cancer cells. Cancer cells serve no useful purpose.

• Loose adherence is typical for cancer cells because they do not make fibronectin. As a result, cancer cells easily break off from the main tumor.

• Migration occurs because cancer cells do not bind tightly together and have many enzymes on their cell surfaces. These features allow the cells to slip through blood vessel walls and between tissues, spreading from the main tumor site to many other body sites. This ability to spread (metastasize) is unique to cancer cells and a major cause of death. Cancer cells expand by mitosis and invade other tissues, both close by and more remote from the original tumor. Invasion and persistent growth make untreated cancer deadly.

• Contact inhibition does not occur in cancer cells, even when all sides of these cells are in continuous contact with the surfaces of other cells. This persistence of cell division makes the disease difficult to control.

• Rapid or continuous cell division occurs in many types of cancer cells because they re-enter the cell cycle for mitosis almost continuously. In addition, some cancer cells have a short generation time (2 to 4 hours), but most cancer cells have a generation time similar to that of the parent cells. These cells also do not respond to signals for apoptosis. Most cancer cells have a lot of the enzyme telomerase, which maintains telomeric DNA. As a result, cancer cells do not respond to apoptotic signals and have an unlimited life span (are “immortal”).

• Abnormal chromosomes (aneuploidy) are common in cancer cells as they become more malignant. Chromosomes are lost, gained, or broken; thus cancer cells can have more than 23 pairs or fewer than 23 pairs. Cancer cells also may have broken and rearranged chromosomes.

Cancer Development

Carcinogenesis/Oncogenesis

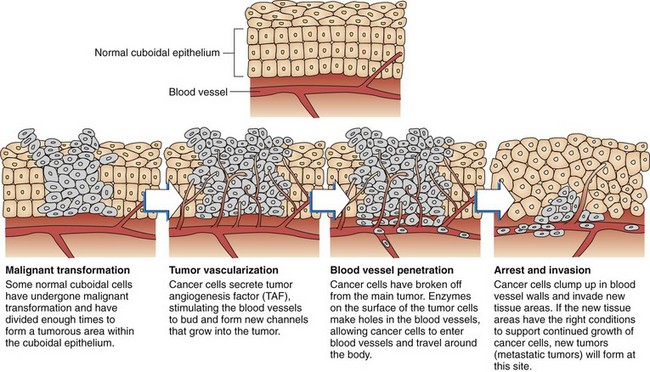

Carcinogenesis and oncogenesis are other names for cancer development. Table 23-2 lists key concepts about cancer development. The process of changing a normal cell into a cancer cell is called malignant transformation, occurring through the steps of initiation, promotion, progression, and metastasis.

TABLE 23-2 KEY CONCEPTS RELATED TO CANCER DEVELOPMENT

Substances that change the activity of a cell’s genes so that the cell becomes a cancer cell are carcinogens. Carcinogens may be chemicals, physical agents, or viruses. There are more than 50 substances known to cause cancer and about another two hundred that are suspected to be carcinogens. The National Toxicology Program’s website lists these substances (http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Chapters presenting the care of patients with specific cancers discuss specific carcinogens (when known) within the Etiology sections.

Metastasis occurs when cancer cells move from the primary location by breaking off from the original group and establishing remote colonies. These additional tumors are called metastatic or secondary tumors. Even though the tumor is now in another organ, it is still a cancer from the original altered tissue. For example, when breast cancer spreads to the lung and the bone, it is still breast cancer in the lung and bone—not lung cancer and not bone cancer. Metastasis occurs through many steps, as shown in Fig. 23-5.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree