Bowel Elimination

Objectives

• Discuss the role of gastrointestinal organs in digestion and elimination.

• Describe three functions of the large intestine.

• Explain the physiological aspects of normal defecation.

• Discuss psychological and physiological factors that influence the elimination process.

• Describe common physiological alterations in elimination.

• Assess a patient’s elimination pattern.

• List nursing diagnoses related to alterations in elimination.

• Describe nursing implications for common diagnostic examinations of the gastrointestinal tract.

• List nursing interventions that promote normal elimination.

• List nursing interventions included in bowel training.

• Discuss nursing care measures required for patients with a bowel diversion.

• Use critical thinking in the provision of care to patients with alterations in bowel elimination.

Key Terms

Bowel training, p. 1110

Cathartics, p. 1091

Clostridium difficile, p. 1092

Colostomy, p. 1093

Constipation, p. 1091

Diarrhea, p. 1092

Effluent, p. 1109

Endoscopy, p. 1091

Enema, p. 1107

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT), p. 1099

Flatulence, p. 1092

Hemorrhoids, p. 1092

Ileostomy, p. 1093

Impaction, p. 1091

Incontinence, p. 1092

Laxatives, p. 1091

Paralytic ileus, p. 1091

Polyps, p. 1094

Stoma, p. 1093

Valsalva maneuver, p. 1089

Wound ostomy continence nurse (WOCN), p. 1109

![]()

Regular elimination of bowel waste products is essential for normal body functioning. Alterations in bowel elimination are often early signs or symptoms of problems within either the gastrointestinal (GI) or other body systems. Because bowel function depends on the balance of several factors, elimination patterns and habits vary among individuals.

Understanding normal bowel elimination and factors that promote, impede, or cause alterations in elimination help manage patients’ elimination problems. Supportive nursing care respects the patient’s privacy and emotional needs. Measures designed to promote normal elimination also need to minimize discomfort for the patient.

Scientific Knowledge Base

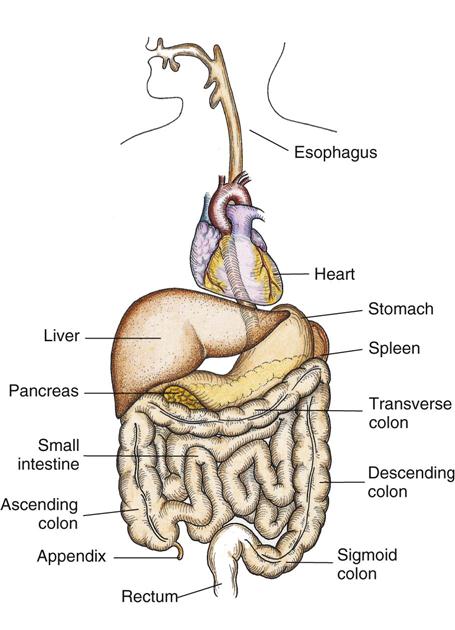

The GI tract is a series of hollow mucous membrane–lined muscular organs. These organs absorb fluid and nutrients, prepare food for absorption and use by body cells, and provide for temporary storage of feces (Fig. 46-1). The GI tract absorbs high volumes of fluids, making fluid and electrolyte balance a key function of the GI system. In addition to ingested fluids and foods, the GI tract also receives secretions from the gallbladder and pancreas.

Mouth

Digestion begins in the mouth and ends in the small intestine. The mouth mechanically and chemically breaks down nutrients into a usable size and form. The teeth masticate food, breaking it down into a size suitable for swallowing. Saliva, produced by the salivary glands in the mouth, dilutes and softens the food in the mouth for easier swallowing.

Esophagus

As food enters the upper esophagus, it passes through the upper esophageal sphincter, a circular muscle that prevents air from entering the esophagus and food from refluxing into the throat. The bolus of food travels down the esophagus and is pushed along by peristalsis, which propels it through the length of the GI tract.

As food moves down the esophagus, it reaches the cardiac or lower esophageal sphincter, which lies between the esophagus and the upper end of the stomach. The sphincter prevents reflux of stomach contents back into the esophagus.

Stomach

The stomach performs three tasks: storing swallowed food and liquid; mixing food, liquid, and digestive juices; and emptying its contents into the small intestine. It produces and secretes hydrochloric acid (HCl), mucus, the enzyme pepsin, and the intrinsic factor. Pepsin and HCl facilitate the digestion of protein. Mucus protects the stomach mucosa from acidity and enzyme activity. The intrinsic factor is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12.

Small Intestine

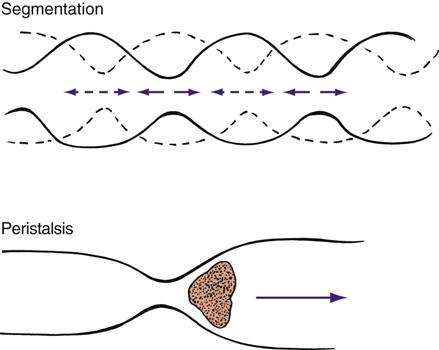

Segmentation and peristaltic movement in the small intestine facilitate both digestion and absorption (Fig. 46-2). Chyme mixes with digestive juices (e.g., bile and amylase). Resorption in the small intestine is so efficient that, by the time the chyme reaches the end of the small intestine, it is pastelike in consistency.

The small intestine has three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. The duodenum is approximately 20 to 28 cm (8 to 11 inches) long and continues to process the chyme from the stomach. The jejunum is approximately 2.5 m (8 feet) long and absorbs carbohydrates and proteins. The ileum is approximately 3.7 m (12 feet) long and absorbs water, fats, certain vitamins, iron, and bile salts. The duodenum and jejunum absorb most of the nutrients and electrolytes. The intestinal wall also absorbs nutrients across the mucosa and into lymph fluids or blood vessels. Substances, such as plant fiber, that the small intestine cannot digest empty into the cecum at the lower right side of the abdomen. The large intestine begins at the cecum.

Impairment of the small intestine alters the digestive process. For example, conditions such as inflammation, surgical resection, or obstruction disrupt peristalsis, reduce the area of absorption, or block the passage of chyme. Electrolyte and nutrient deficiencies then develop.

Large Intestine

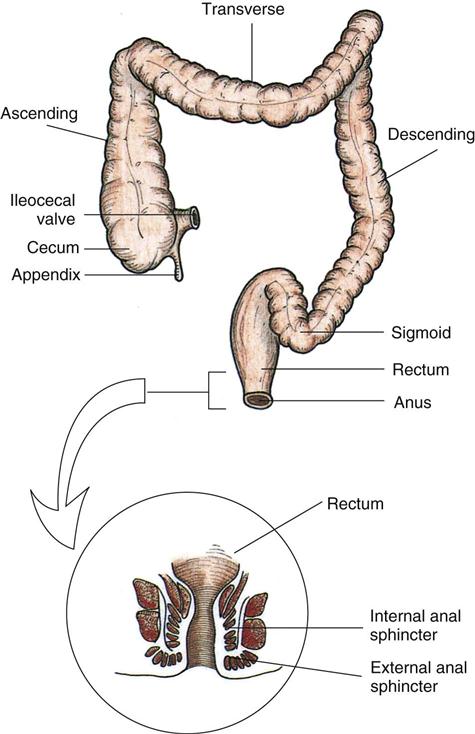

The lower GI tract is called the large intestine (colon) because it is larger in diameter than the small intestine. The large intestine is shorter (1.5 to 1.8 m [5 to 6 feet]) but much wider than the small intestine. The large intestine is divided into the cecum, colon, and rectum (Fig. 46-3). The large intestine is the primary organ of bowel elimination. It is positioned like a question mark, partially encircling the small intestine.

Chyme enters the large intestine by waves of peristalsis through the ileocecal valve, a circular muscular layer that prevents regurgitation. The colon is divided into the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colons. The muscular tissue of the colon allows it to accommodate and eliminate large quantities of waste and gas (flatus). It has three functions: absorption, secretion, and elimination. The large intestine absorbs water, sodium, and chloride from the digested food that has passed from the small intestine. Healthy adults absorb more than a gallon of water and an ounce of salt from the colon every 4 hours. The amount of water absorbed from chyme depends on the speed at which colonic contents move. Chyme is normally a soft, formed mass. If peristalsis is abnormally fast, there is less time for water to be absorbed, and the stool is watery. If peristaltic contractions slow, water continues to be absorbed; and a hard mass of stool forms, resulting in constipation (JBI, 2008).

The secretory function of the colon aids in electrolyte balance. The colon secretes bicarbonate in exchange for chloride. The colon also excretes about 4 to 9 mEq of potassium daily. Therefore serious alterations in colon function (e.g., diarrhea) cause severe electrolyte disturbances.

Slow peristaltic contractions move contents through the colon. Intestinal content is the main stimulus for contraction. Mass peristalsis pushes undigested food toward the rectum. These mass movements occur only three or four times daily, with the strongest during the hour after mealtime.

The rectum is the final portion of the large intestine. Here bacteria convert fecal matter into its final form. Normally the rectum is empty of waste products (feces) until just before defecation. It contains vertical and transverse folds of tissue that help to temporarily hold fecal contents during defecation. Each fold contains an artery and vein that can become distended from pressure during straining. This distention often results in hemorrhoid formation.

Anus

The body expels feces and flatus from the rectum through the anal canal and anus. Contraction and relaxation of the internal and external sphincters, innervated by sympathetic and parasympathetic stimuli, aid in the control of defecation. The anal canal is richly supplied with sensory nerves that help to control continence.

Defecation

The physiological factors critical to bowel function and defecation include normal GI tract function, sensory awareness of rectal distention and rectal contents, voluntary sphincter control, and adequate rectal capacity and compliance. Normal defecation begins with movement in the left colon, moving stool toward the anus. When stool reaches the rectum, the distention causes relaxation of the internal sphincter and an awareness of the need to defecate. At the time of defecation, the external sphincter relaxes, and abdominal muscles contract, increasing intrarectal pressure and forcing the stool out (Huether and McCance, 2008). Sometimes people use the Valsalva maneuver to assist in stool passage. The Valsalva maneuver exerts pressure to expel feces through a voluntary contraction of the abdominal muscles while maintaining forced expiration against a closed airway. Patients with cardiovascular disease, glaucoma, increased intracranial pressure, or a new surgical wound are at greater risk for cardiac dysrhythmias and elevated blood pressure with the Valsalva maneuver and need to avoid straining to pass the stool. Normal defecation is painless, resulting in passage of soft, formed stool.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Factors Influencing Bowel Elimination

Many factors influence the process of bowel elimination. Knowledge of these factors helps to anticipate measures required to maintain a normal elimination pattern.

Age

Developmental changes affecting elimination occur throughout life. An infant has a small stomach capacity and less secretion of digestive enzymes. Food passes quickly through an infant’s intestinal tract because of rapid peristalsis. The infant is unable to control defecation because of a lack of neuromuscular development. This neuromuscular development usually does not take place until 2 to 3 years of age.

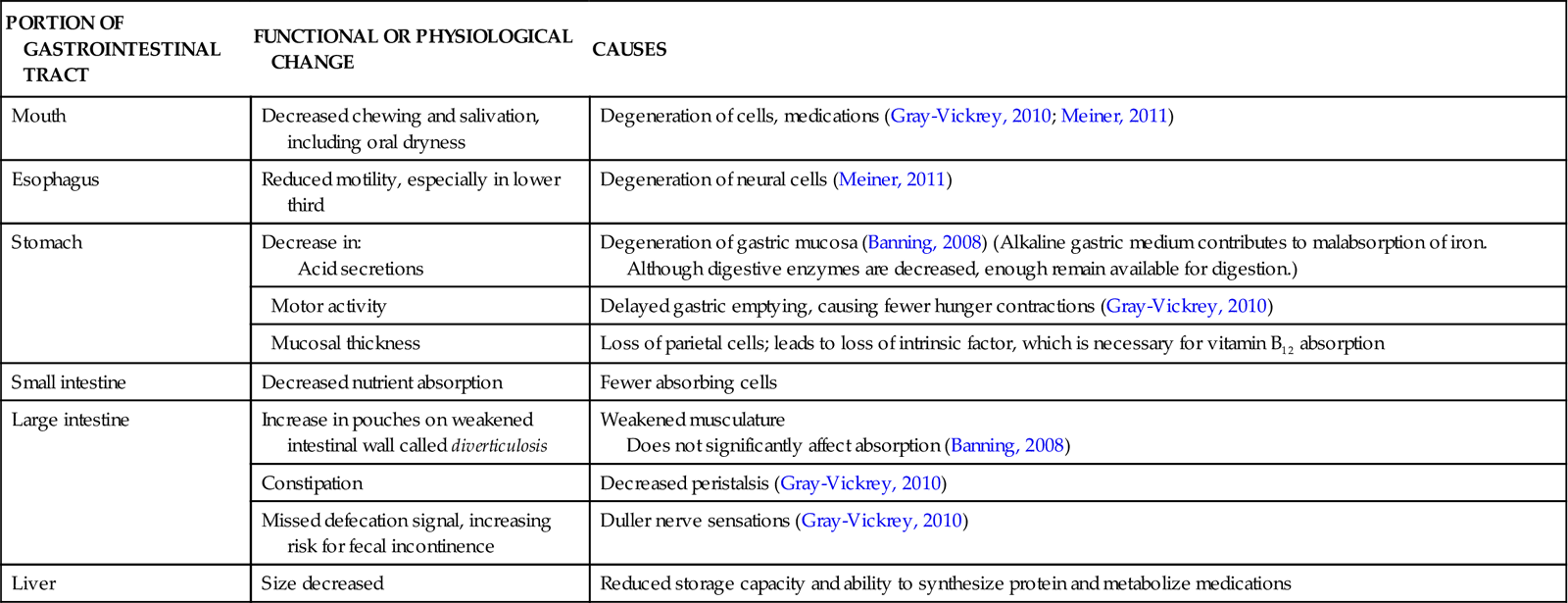

Systemic changes in the function of digestion and absorption of nutrients result from changes in older patients’ cardiovascular and neurological systems rather than their GI system. For example, arteriosclerosis causes decreased mesenteric blood flow, thus decreasing absorption from the small intestine (Meiner, 2011). In addition, peristalsis decreases, and esophageal emptying slows. Older adults often experience changes in the GI system that impair digestion and elimination (JBI, 2008) (Table 46-1).

TABLE 46-1

Normal Age-Related Changes in the Gastrointestinal Tract

| PORTION OF GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT | FUNCTIONAL OR PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGE | CAUSES |

| Mouth | Decreased chewing and salivation, including oral dryness | Degeneration of cells, medications (Gray-Vickrey, 2010; Meiner, 2011) |

| Esophagus | Reduced motility, especially in lower third | Degeneration of neural cells (Meiner, 2011) |

| Stomach | Decrease in: Acid secretions | Degeneration of gastric mucosa (Banning, 2008) (Alkaline gastric medium contributes to malabsorption of iron. Although digestive enzymes are decreased, enough remain available for digestion.) |

| Motor activity | Delayed gastric emptying, causing fewer hunger contractions (Gray-Vickrey, 2010) | |

| Mucosal thickness | Loss of parietal cells; leads to loss of intrinsic factor, which is necessary for vitamin B12 absorption | |

| Small intestine | Decreased nutrient absorption | Fewer absorbing cells |

| Large intestine | Increase in pouches on weakened intestinal wall called diverticulosis | Weakened musculature Does not significantly affect absorption (Banning, 2008) |

| Constipation | Decreased peristalsis (Gray-Vickrey, 2010) | |

| Missed defecation signal, increasing risk for fecal incontinence | Duller nerve sensations (Gray-Vickrey, 2010) | |

| Liver | Size decreased | Reduced storage capacity and ability to synthesize protein and metabolize medications |

Older adults also lose muscle tone in the perineal floor and anal sphincter (Holman et al., 2008). Although the integrity of the sphincter remains intact, they often have difficulty controlling bowel evacuation and are at risk for incontinence. In addition, nerve impulses to the anal region slow, causing some individuals to become less aware of the need to defecate. Older adults, especially residents in long-term care facilities, sometimes develop irregular bowel movements and an increased risk for constipation (Kyle, 2007a).

Diet

Regular daily food intake helps maintain a regular pattern of peristalsis in the colon. Fiber, the nondigestible residue in the diet, provides the bulk of fecal material. Bulk-forming foods such as whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables help flush the fats and waste products from the body with more efficiency (Holman et al., 2008). The bowel walls stretch, creating peristalsis and initiating the defecation reflex. With stimulation of peristalsis, bulk foods pass quickly through the intestines, keeping the stool soft. Ingestion of a high-fiber diet improves the likelihood of a normal elimination pattern if other factors are normal. Diets high in vegetables and fruits have been linked to decreased risk of colorectal cancer (ACS, 2011b).

Gas-producing foods such as onions, cauliflower, and beans also stimulate peristalsis. The gas formed distends intestinal walls and increases colon motility. Some spicy foods increase peristalsis but also cause indigestion and watery stools.

Food intolerance is not an allergy but rather a particular food that causes the body distress within a few hours of ingestion. The result is diarrhea, cramps, or flatulence. For example, people who drink cow’s milk and have these symptoms are not allergic to milk but lack the enzyme needed to digest the milk sugar lactase and therefore are lactose intolerant. Another condition called celiac disease is a syndrome in which the patient has a hypersensitivity to protein in certain cereal grains and gluten.

Fluid Intake

An inadequate fluid intake or disturbances resulting in fluid loss (such as vomiting) affect the character of feces. Fluid liquefies intestinal contents, easing its passage through the colon. Reduced fluid intake slows passage of food through the intestine and results in hardening of stool contents. Unless there is a medical contraindication, an adult needs to drink at least 1100 to 1400 mL of fluid daily. An increase in fluid intake with the use of fruit juices softens stool and increases peristalsis. Poor fluid intake increases the risk of constipation because of greater resorption of fluid in the colon, resulting in hard, dry stools (Kyle, 2007a).

Physical Activity

Physical activity promotes peristalsis, whereas immobilization depresses it. Encourage early ambulation as illness begins to resolve or as soon as possible after surgery to promote maintenance of peristalsis and normal elimination. Maintaining tone of skeletal muscles used during defecation is important. Weakened abdominal and pelvic floor muscles impair the ability to increase intraabdominal pressure and control the external sphincter. Muscle tone is sometimes weakened or lost as a result of long-term illness, spinal cord injury, or neurological disease that impairs nerve transmission. As a result of these changes in the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles, there is an increased risk for constipation.

Psychological Factors

Prolonged emotional stress impairs the function of almost all body systems (see Chapter 37). During emotional stress the digestive process is accelerated, and peristalsis is increased. Side effects of increased peristalsis are diarrhea and gaseous distention. A number of diseases of the GI tract are associated with stress, including ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, certain gastric and duodenal ulcers, and Crohn’s disease. If a person becomes depressed, the autonomic nervous system slows impulses; peristalsis decreases, resulting in constipation.

Personal Habits

Personal elimination habits influence bowel function. Most people benefit from being able to use their own toilet facilities at a time that is most effective and convenient for them. A busy work schedule sometimes prevents the individual from responding appropriately to the urge to defecate, disrupting regular habits and causing possible alterations such as constipation. Individuals need to recognize the best time for elimination.

Chronically ill and hospitalized patients are not always able to maintain privacy during defecation. In a hospital or extended care setting, patients sometimes share bathroom facilities with a roommate with different hygienic habits. In addition, chronic illness limits a patient’s balance, activity tolerance, or physical activity and requires the use of a bedpan or bedside commode. The sights, sounds, and odors associated with sharing toilet facilities or using bedpans are often embarrassing. This embarrassment often causes patients to ignore the urge to defecate, which begins a vicious cycle of constipation and discomfort.

Position During Defecation

Squatting is the normal position during defecation. Modern toilets facilitate this posture, allowing the person to lean forward, exert intraabdominal pressure, and contract the thigh muscles. For the patient immobilized in bed, defecation is often difficult. In a supine position it is impossible to contract the muscles used during defecation. If the patient’s condition permits, raise the head of the bed to assist the patient to a more normal sitting position on a bedpan, enhancing the ability to defecate.

Pain

Normally the act of defecation is painless. However, a number of conditions such as hemorrhoids, rectal surgery, rectal fistulas, and abdominal surgery result in discomfort. In these instances the patient often suppresses the urge to defecate to avoid pain, contributing to the development of constipation.

Pregnancy

As pregnancy advances, the size of the fetus increases, and pressure is exerted on the rectum. A temporary obstruction created by the fetus impairs passage of feces. Slowing of peristalsis during the third trimester often leads to constipation. A pregnant woman’s frequent straining during defecation or delivery results in formation of permanent hemorrhoids.

Surgery and Anesthesia

General anesthetic agents used during surgery cause temporary cessation of peristalsis (see Chapter 50). Inhaled anesthetic agents block parasympathetic impulses to the intestinal musculature. The action of the anesthetic slows or stops peristaltic waves. The patient who receives a local or regional anesthetic is less at risk for elimination alterations because this type of anesthesia generally affects bowel activity minimally or not at all.

Any surgery that involves direct manipulation of the bowel temporarily stops peristalsis. This condition, called paralytic ileus, usually lasts about 24 to 48 hours. If the patient remains inactive or is unable to eat after surgery, return of normal bowel elimination is further delayed.

Medications

Some medications have certain expected actions on the bowel (e.g., there are medications to promote defecation or control diarrhea). In addition, medications prescribed for acute and chronic conditions often have secondary effects on the patient’s bowel elimination patterns (Table 46-2).

TABLE 46-2

Medications and the Gastrointestinal System

| MEDICATIONS | ACTION |

| Dicyclomine HCl (Bentyl) | Suppresses peristalsis and decreases gastric emptying |

| Opioid analgesics | Slow peristalsis and segmental contractions, often resulting in constipation (Lehne, 2010) |

| Anticholinergic drugs such as atropine or glycopyrrolate (Robinul) | Inhibit gastric acid secretion and depress gastrointestinal (GI) motility (Lehne, 2010) (Although useful in treating hyperactive bowel disorders, anticholinergics cause constipation.) |

| Antibiotics | Produce diarrhea by disrupting the normal bacterial flora in the GI tract (An increase in the use of fluoroquinolones in recent years has provided a selective advantage for the epidemic of Clostridium difficile) (Vonberg et al., 2008) |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Cause GI irritation that increases the incidence of bleeding with serious consequences to older adults; rectal bleeding is often observed with GI irritation (Lehne, 2010) |

| Aspirin | Prostaglandin inhibitor; interferes with the formation and production of protective mucus and causes GI bleeding (Lehne, 2010) |

| Histamine2 (H2) antagonists | Suppress the secretion of hydrochloric acid and interfere with the digestion of some foods |

| Iron | Causes discoloration of the stool (black), nausea, vomiting, constipation (diarrhea is less commonly reported), and abdominal cramps (Lehne, 2010) |

Laxatives and cathartics soften the stool and promote peristalsis. Although similar, laxatives are milder in action than cathartics. When used correctly, laxatives and cathartics safely maintain normal elimination patterns. However, chronic use of cathartics causes the large intestine to become less responsive to stimulation by laxatives. Laxative overuse can also cause serious diarrhea, leading to dehydration and electrolyte depletion. Mineral oil, a common laxative, decreases fat-soluble vitamin absorption. Laxatives often influence the efficacy of other medications by altering the transit time (i.e., the time the medication remains in the GI tract and is available for absorption).

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic examinations involving visualization of GI structures often require a prescribed bowel preparation (e.g., medications, cathartics, and/or enemas) to ensure that the bowel is empty. In addition, the patient cannot eat or drink several hours before the examinations such as an endoscopy, colonoscopy, or other testing that requires visualization of the GI tract. Following the diagnostic procedure, changes in elimination such as increased gas or loose stools often occur until the patient resumes a normal eating pattern.

Common Bowel Elimination Problems

Caring for patients who have or are at risk for elimination problems because of emotional stress (anxiety or depression), physiological changes in the GI tract such as surgical alteration of intestinal structures, inflammatory diseases, prescribed therapy, or disorders impairing defecation is common in the practice of nursing.

Constipation

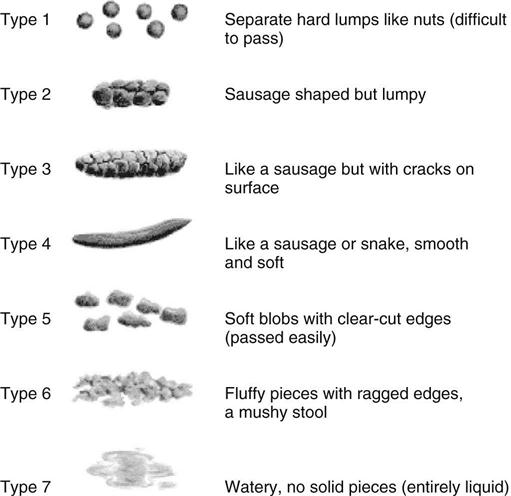

Constipation is a symptom, not a disease (Box 46-1). Improper diet, reduced fluid intake, lack of exercise, and certain medications can cause constipation. For example, patients receiving opiates for pain after surgery often require a stool softener or laxative to prevent constipation. The signs of constipation include infrequent bowel movements (less than every 3 days), difficulty passing stools, excessive straining, inability to defecate at will, and hard feces (McWilliams, 2010). When intestinal motility slows, the fecal mass becomes exposed over time to the intestinal walls, and most of the fecal water content is absorbed. Little water is left to soften and lubricate the stool. Passage of a dry, hard stool causes rectal pain (Fig. 46-4).

Constipation is a significant health hazard. Straining during defecation causes problems for the patient with recent abdominal, gynecological, or rectal surgery. The effort to pass a stool often causes sutures to separate, reopening the wound. In addition, patients with histories of cardiovascular disease, diseases causing elevated intraocular pressure (glaucoma), and increased intracranial pressure need to prevent constipation and avoid using the Valsalva maneuver.

Impaction

Fecal impaction results from unrelieved constipation. It is a collection of hardened feces wedged in the rectum that a person cannot expel. In cases of severe impaction the mass extends up into the sigmoid colon. If not resolved or removed, severe impaction often results in intestinal obstruction. Patients who are debilitated, confused, or unconscious are most at risk for impaction. They are dehydrated or too weak or unaware of the need to defecate, and the stool becomes too hard and dry to pass.

An obvious sign of impaction is the inability to pass a stool for several days, despite the repeated urge to defecate (Chien and Bradway, 2010). You suspect impaction when a continuous oozing of diarrhea stool occurs. The liquid portion of feces located higher in the colon seeps around the impacted mass. Loss of appetite (anorexia), nausea and/or vomiting, abdominal distention and cramping, and rectal pain often accompany the condition. If an impaction is suspected, gently perform a digital examination of the rectum and palpate for the impacted mass (Steggall, 2008).

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is an increase in the number of stools and the passage of liquid, unformed feces. It is associated with disorders affecting digestion, absorption, and secretion in the GI tract. Intestinal contents pass through the small and large intestine too quickly to allow for the usual absorption of fluid and nutrients. Irritation within the colon results in increased mucus secretion. As a result, feces become watery, and the patient is unable to control the urge to defecate. Normally an anal bag is safe and effective in long-term treatment of patients with fecal incontinence at home, in hospice, or in the hospital. Fecal incontinence is expensive and a potentially dangerous condition in terms of contamination and risk of skin ulceration (Gray, 2007).

Excess loss of colonic fluid results in serious fluid and electrolyte or acid-base imbalances. Infants and older adults are particularly susceptible to associated complications (see Chapter 41). Because repeated passage of diarrhea stools also exposes the skin of the perineum and buttocks to irritating intestinal contents, meticulous skin care and containment of fecal drainage is necessary to prevent skin breakdown (see Chapter 48).

Many conditions cause diarrhea. Antibiotic use via any route of administration alters the normal flora in the GI tract (Vonberg et al., 2008). Patients receiving enteral nutrition are also at risk for diarrhea. Consult a dietitian when diarrhea occurs (Tabloski, 2009). See Chapter 44 for interventions to decrease diarrhea caused by enteral feedings. Food allergies and intolerances increase peristalsis and cause diarrhea. Surgeries or diagnostic testing of the lower GI tract also cause diarrhea. The aim of treatment is to remove precipitating conditions and slow peristalsis.

Another common causative agent of diarrhea is Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), in which symptoms range from mild diarrhea to severe colitis. C. difficile infection is acquired in one of two ways: by factors that cause an overgrowth of C. difficile, and by contact with the C. difficile organism. A new strain of C. difficile has been identified that is more virulent with more toxic effects (Grossman, 2010). Antibiotics (cephalosporins, ampicillin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin (Calfee, 2008), chemotherapy, and invasive bowel procedures such as surgery or colonoscopy disrupt normal bowel flora and may cause an overgrowth of C. difficile. Some patients acquire the organism from a health care worker’s hands or direct contact with the environmental surfaces contaminated with it. Only hand hygiene with soap and water is effective to physically remove C. difficile spores from the hands. In addition, evidence supports the use of diluted bleach (1 : 10) as an environmental disinfectant to decrease the incidence of C. difficile (Calfee, 2008; Vonberg, 2008). The most common diagnostic test for the bacteria is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, which detects C. difficile A and B in the stool.

Communicable foodborne pathogens also cause diarrhea. Hand hygiene following the use of the bathroom, before and after preparing foods, and when cleaning and storing fresh produce and meats greatly reduces the risk of foodborne illnesses. When diarrhea is the result of a foodborne virus, the goal usually is to rid the GI system of the pathogen rather than slow peristalsis.

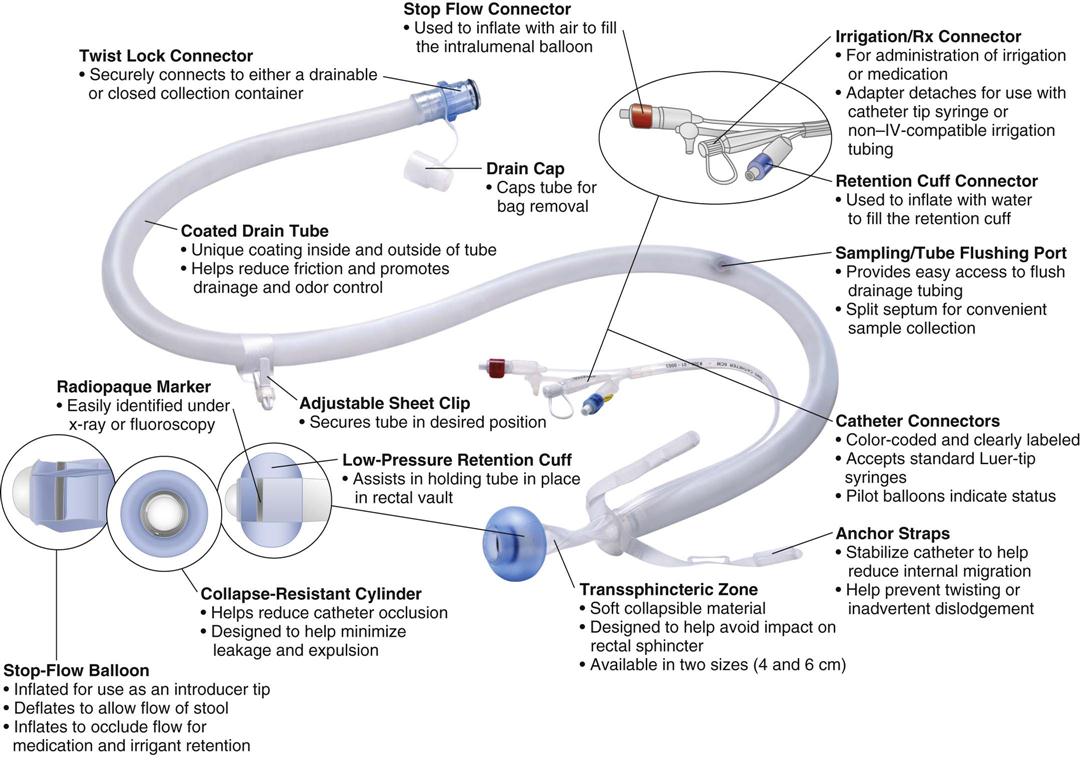

Incontinence

Fecal incontinence is the inability to control passage of feces and gas from the anus. Incontinence harms a patient’s body image (see Chapter 33). In many situations the patient is mentally alert but physically unable to avoid defecation. The embarrassment of soiling clothes often leads to social isolation. Physical conditions that impair anal sphincter function or control cause incontinence. It occurs in a variety of settings. Conditions that create frequent, loose, large-volume, watery stools also predispose to incontinence. Using an anal bag or a bowel management system helps to prevent perineal skin breakdown (Fig. 46-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree