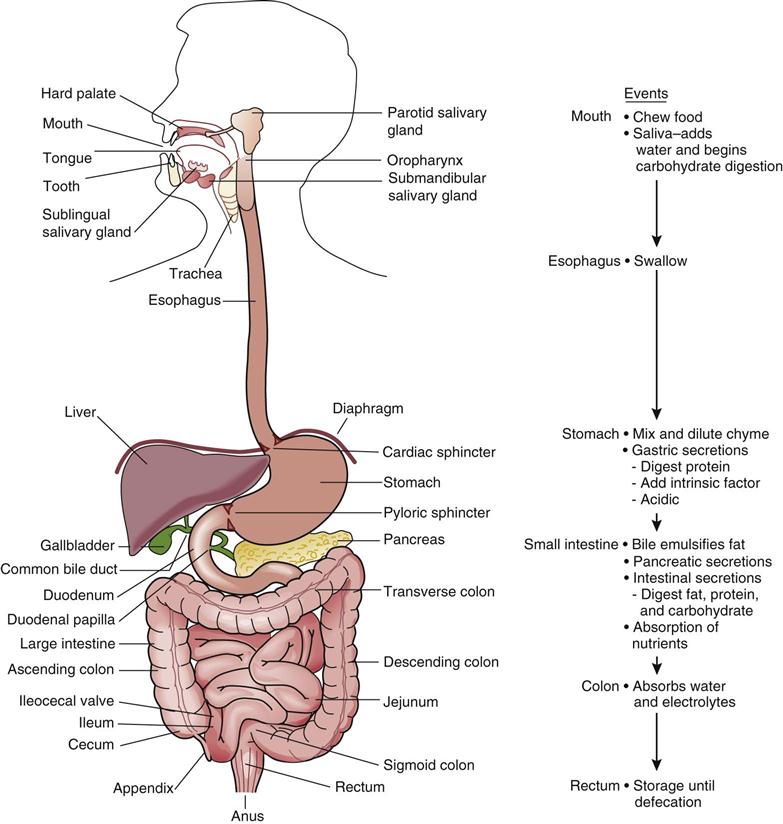

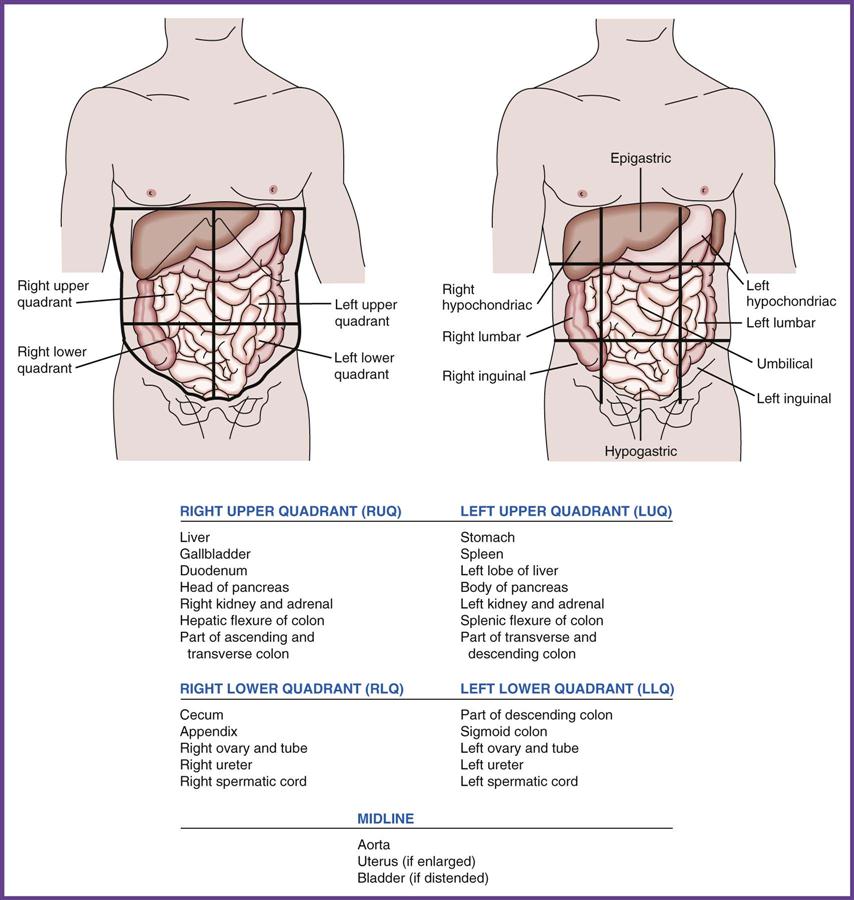

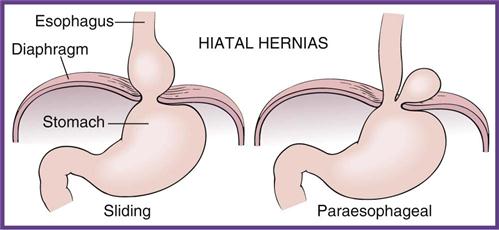

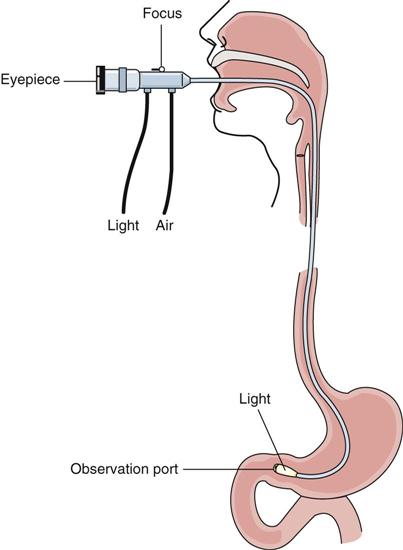

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care. 3. Describe the primary functions of the GI system. 4. Identify the anatomic structures that make up the GI system and describe the physiology of each. 5. Differentiate among the abdominal quadrants and regions. 6. Summarize the typical symptoms and characteristics of GI complaints. 7. Perform telephone screening for patients with GI complaints. 8. Distinguish among cancers of the GI tract. 10. Describe intestinal disorders, the signs and symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatments. 12. Describe the similarities and differences among the various forms of infectious viral hepatitis. 13. Summarize the medical assistant’s role in the GI examination. 14. Explain the common diagnostic procedures for the GI system. 15. Demonstrate the procedure for assisting with an endoscopic colon examination. 16. Perform the procedural steps for assisting with the collection of a fecal specimen. 17. Describe the medical assistant’s role in the proctologic examination. adhesions (ad-he′-zhuns) Bands of scar tissue that bind together two anatomic surfaces that normally are separate. anastomosis (uh-nas-tuh-mo′-suhs) The surgical joining of two normally distinct organs. anorexia (a-nuh-rek′-se-uh) A lack or loss of appetite for food. ascites (uh-si′-tez) An abnormal collection of fluid containing high levels of protein and electrolytes in the peritoneal cavity. carcinogens (kar-si′-nuh-juhns) Substances or agents that cause the development or increase the incidence of cancer. endemic (en-de′-mik) Term describing a disease or microorganism that is specific to a particular geographic area. esophageal varices (i-sah-fuh-je′-uhl var′-uh-sez) Varicose veins of the esophagus that occur as a result of portal hypertension; these vessels can easily hemorrhage. fecalith (fe′-kuh-lith) A hard, impacted mass of feces in the colon. fissures Narrow slits or clefts in the abdominal wall. fistula (fis′-chuh-luh) An abnormal, tubelike passage between internal organs or from an internal organ to the body’s surface. flatus Gas expelled through the anus. hematemesis (hi-mat-uh-me′-sis) Vomiting of bright red blood, indicating rapid upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding; associated with esophageal varices or peptic ulcer. hematocrit The percentage by volume of packed red blood cells in a given sample of blood after centrifugation. hemoglobin (he′-muh-glo-buhn) A protein found in erythrocytes that transports molecular oxygen in the blood. hepatomegaly (he-puh-to-me′-guh-le) Abnormal enlargement of the liver. lithotripsy (li′-thuh-trip-se) A procedure for eliminating a kidney stone or gallstone by crushing or dissolving it in situ through the use of high-intensity sound waves. lymphadenopathy (lim-fa-duh-nah′-puh-the) Any disorder of the lymph nodes or lymph vessels. peristalsis The rhythmic, involuntary serial contraction of the smooth muscles lining the GI tract. polyps (pah′-lips) Tumors or outgrowths found in the mucosal lining of the colon; they are considered precancerous. portal circulation The pathway of blood flow through the portal vein from the GI system to the liver. portal hypertension Increased venous pressure in the portal circulation caused by cirrhosis or compression of the hepatic vascular system. pyloric sphincter A muscular ring at the distal end of the stomach that separates the stomach from the duodenum of the small intestine. sclerotherapy (skluh-rah-ther′-ah-pe) The treatment of hemorrhoids, varicose veins, or esophageal varices by means of injection of sclerosing solutions. Joan Rothman, CMA (AAMA), was recently hired by United Community Hospital to work for a group of internists. Joan works primarily with Dr. Raj Sahani, a physician who specializes in gastroenterology. Although Joan did very well in school, she has had to learn more advanced information about disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract so that she can answer patients’ questions and understand the diagnostic procedures ordered by Dr. Sahani. Dr. Sahani has asked Joan to research and develop educational packets for common gastrointestinal studies and to work with other staff members on understanding procedures related to the GI system. Part of the role of the medical assistant working in a gastroenterology practice is to conduct routine patient education so that patients are properly prepared for diagnostic procedures. Joan also is expected to help in the orientation of new staff members. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: Internal medicine is a nonsurgical specialty consisting of several subspecialties. Gastroenterology, one of these subspecialties, covers an extremely wide area known as the gastrointestinal (GI) system, or the alimentary canal. Gastroenterologists are concerned with diseases and disorders of the stomach, small intestine, large intestine (colon), appendix, and accessory organs of the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Proctology, a subspecialty of gastroenterology, is concerned with disorders of the rectum and anus. The major purpose of the GI system is to prepare, digest, and absorb the necessary nutrients to maintain homeostasis and excrete waste products through the feces. The GI system is basically a long, hollow tube with the same structural organization from its beginning to its termination (Figure 39-1). The muscles lining the GI tract are closely regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which gives the entire system its unique ability to move slowly in some locations and to have increased movement in other sections. The GI system is divided into two parts: the upper digestive system, which includes the mouth, esophagus, and stomach, and the lower digestive system, which consists of the small and large intestines. The GI tract is rich in lymphatic tissue, which is very important for the absorption of nutrients from ingested food. Unfortunately, the lymphatic vessels also are the main route for the spread of cancer. As mentioned, the GI organs have three primary functions: digestion, absorption, and elimination. When food is taken in through the mouth, it is chewed, or masticated, and moistened with saliva. Salivary amylase, an enzyme released by the salivary glands, mixes with the food and begins carbohydrate digestion. This mass, now called a bolus, is swallowed, and the food enters the esophagus. Contractions of the smooth muscles are activated, and the bolus is moved by peristalsis down the esophagus and into the stomach. At the distal end of the esophagus is the gastroesophageal or cardiac sphincter, which relaxes as the bolus is swallowed so that it can pass into the stomach. The muscular walls of the stomach overlap in folds, or rugae, which permit the stomach to expand and to hold as much as 1 to 1.5 L of food and liquid. The gastric glands in the stomach mucosa secrete hydrochloric acid, pepsinogen (which begins the digestion of protein), and intrinsic factor, which is needed for the absorption of vitamin B12. The gastric contents, called chyme, are slowly emptied through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine. The small intestine is made up of the duodenum at the proximal end, the jejunum, and the ileum at the distal end. The common bile duct delivers bile, which is produced in the liver and stored in the gallbladder, to the duodenum. Bile acids emulsify fat, that is, they break down large fat molecules into smaller molecules that can be chemically digested by fat enzymes. The pancreatic duct delivers digestive enzymes to the duodenum, including amylase for carbohydrate digestion, trypsin for protein breakdown, and lipase for fats. This mixture of bile and pancreatic enzymes in the duodenum completes the digestion of nutrients, converting carbohydrates into glucose, protein into amino acids, and fats into fatty acids and glycerol. Once digestion has been completed in the duodenum, the second function of the GI tract, absorption of nutrients, begins. The small intestine is lined with transverse folds of tissue called villi. Approximately 25,000 of these overlapping projections greatly increase the surface area available in the small intestine for nutrient absorption. Each villus is rich with blood vessels that absorb digested nutrients into the portal circulation system and carry them directly to the liver for processing. Lymph vessels along the villi absorb fat and deposit it into the systemic circulation. By the time the chyme reaches the terminal end of the small intestine, every nutrient the body needs should have been absorbed. This mass enters the colon, or large intestine, which is made up of the cecum (extending from it is the vermiform appendix), ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus. The colon absorbs large amounts of fluids and electrolytes to prevent dehydration of body tissues. Once fluid has been reabsorbed, the remaining solid waste materials, called feces, are moved into the sigmoid colon and rectum, and elimination occurs through the anus. This final function is called defecation. GI disorders probably are the most common problems seen in a medical office. Most conditions of the GI system are managed by a primary care physician. About 5% to 10% of patients with GI problems are referred to a gastroenterologist for diagnosis and treatment. It is assumed that problems that stem from dental disorders are treated by dental professionals. This chapter concentrates on the GI problems most frequently seen, diagnosed, and treated in an ambulatory care center. Table 39-1 outlines the typical signs, symptoms, and characteristics seen in patients with GI complaints. Using Procedure 39-1, outline how you would respond to the scenarios in Critical Thinking Application 39-2. TABLE 39-1 Characteristics of Common Gastrointestinal Complaints Any organ of the digestive tract can develop cancer. The features of malignant tumors and their treatments are described in Chapter 38. These characteristics, including the ability to invade surrounding tissues and metastasize through the blood or lymph system, are true of all cancerous tumors.` Table 39-2 describes some of the common malignant tumors found in the GI system. The exact cause of a malignancy may not be known, but exposure to carcinogens increases the risk of developing a cancerous tumor. Examples of carcinogens include tobacco and alcohol, as well as exposure to chemicals and radiation. The family history and lifestyle factors, such as consuming a diet high in fat and low in fiber, also can increase a person’s risk of developing certain types of cancer. TABLE 39-2 Cancers of the Gastrointestinal Tract A hernia is the abnormal protrusion of part of an organ or tissue through the structures that normally contain it. These protrusions can develop in various parts of the body but most frequently are seen in the abdominal region. Causes of herniation include congenital weakness of the structures, trauma, relaxation of ligaments and skeletal muscles, and increased upward pressure from the abdomen. Herniation most often is found in middle-aged or older individuals. The location of the hernia determines the term by which the protrusion is identified. In patients with a hiatal hernia, the upper part of the stomach protrudes through the esophageal opening, the hiatal sphincter of the diaphragm (Figure 39-3). With a sliding hiatal hernia, part of the stomach moves above the diaphragm when the individual is supine and slides back down into the abdominal cavity when the person stands. Part of the fundus of the stomach moves through the weakened hiatus in a paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Food may lodge in the herniated part of the stomach, causing reflux of highly acidic stomach contents into the esophagus, dysphagia, and chronic esophagitis, which may cause fibrosis and stricture. Patients complain of heartburn, frequent belching, and increased discomfort when they cough, bend over, or lie down after eating. Patients with hiatal hernias are treated medically with Prilosec, Nexium, Pepcid, Tagamet, or Zantac. Treatment may include dietary modifications, such as avoiding caffeine, cigarettes, and alcohol; eating six small meals a day; losing weight; avoiding lying down after meals; and raising the head of the bed 6 to 8 inches. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when the gastroesophageal sphincter (cardiac sphincter) at the distal end of the esophagus does not close properly, allowing acidic stomach contents to leak back, or reflux, into the esophagus. The regurgitated acidic contents of the stomach irritate the esophageal lining, causing heartburn symptoms. Occasional heartburn is not a problem, but a patient who experiences heartburn more than twice a week is diagnosed with GERD. All age groups can be diagnosed with GERD; however, it is seen most frequently in adults and is associated with alcohol use, pregnancy, and smoking; it is very common in overweight patients. Besides persistent heartburn, patients may report chest pain, hoarseness in the morning, difficulty swallowing, a feeling of tightness in the throat or a choking sensation, dry cough, and bad breath from the reflux of partly digested food. GERD frequently is seen in patients with hiatal hernias, and treatment protocols are similar in the two conditions. Laparoscopic repair of the gastroesophageal sphincter may be recommended if lifestyle changes and medication are not effective in curing the problem. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an Enteryx implant, which is placed next to the sphincter with an endoscope. The Enteryx device releases a solution that helps strengthen the muscle. The most important concern with chronic GERD is the potential for developing Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition caused by long-term exposure of esophageal cells to gastric contents. Patients diagnosed with GERD are followed regularly by a gastroenterologist so that these abnormal cells can be detected early and removed before cancerous changes occur. Peptic ulcers occur most frequently in the proximal duodenum (duodenal ulcer) but may also be found in the stomach (gastric ulcer). Both types are characterized by an area of breakdown of the mucosal membrane, which leads to ulceration of the epithelial lining of the duodenum or stomach (Figure 39-4). The first sign of a peptic ulcer may be iron-deficiency anemia or a positive stool test for occult blood, which results from erosion of blood vessels in the organ wall. Patients typically complain of gnawing or burning pain in the epigastric area between meals. Gastric ulcers may cause weight loss, whereas duodenal lesions often cause nausea and vomiting. If the ulcerative area is bleeding internally, the patient may have hematemesis (blood in the vomitus) or melena (coffee ground–like vomitus and/or tarry black stools). The description of the patient’s pain gives the physician a suspicion of the disorder. Examination often shows that the patient is guarding the painful area, characterized by clutching the upper abdominal area and drawing the knees up toward the chest. A definitive diagnosis is based on an upper GI series (x-ray evaluation) or endoscopy (visualization) of the upper GI tract (Figure 39-5). A biopsy sample of the affected area may be taken during the endoscopy to rule out cancer. A stool test may be ordered to check for occult (hidden) blood. Blood tests also are ordered to establish the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. Peptic ulcers can appear under a variety of predisposing circumstances, including use of alcohol, smoking, use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), and genetic predisposition. However, research indicates that 80% of gastric ulcers and 90% of duodenal ulcers are caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacterium. H. pylori can be diagnosed either by a blood test that measures the presence of antibodies to the bacteria or by a breath test that is done after the patient swallows a drink containing urea and carbon. Expired air is examined to detect the bacteria. The diagnosis is confirmed with biopsy samples of the gastric and duodenal mucosa obtained during an endoscopic examination. Peptic ulcers caused by H. pylori are treated with a combination of medications, including antibiotics to kill the bacteria and drugs to reduce the production of hydrochloric acid and protect the stomach lining. The most effective treatment is a triple therapy method that lasts 2 weeks and includes two antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin, Flagyl, Biaxin) and either a histamine blocker (e.g., Tagamet, Zantac) or a proton pump inhibitor (e.g., Prilosec, Prevacid). Surgery may be indicated in severe cases, such as with perforation of the gastric wall. Any ulcer that does not heal is re-evaluated periodically through gastroscopy to rule out cancer.

Assisting in Gastroenterology

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Anatomy and Physiology

Diseases of the Gastrointestinal System

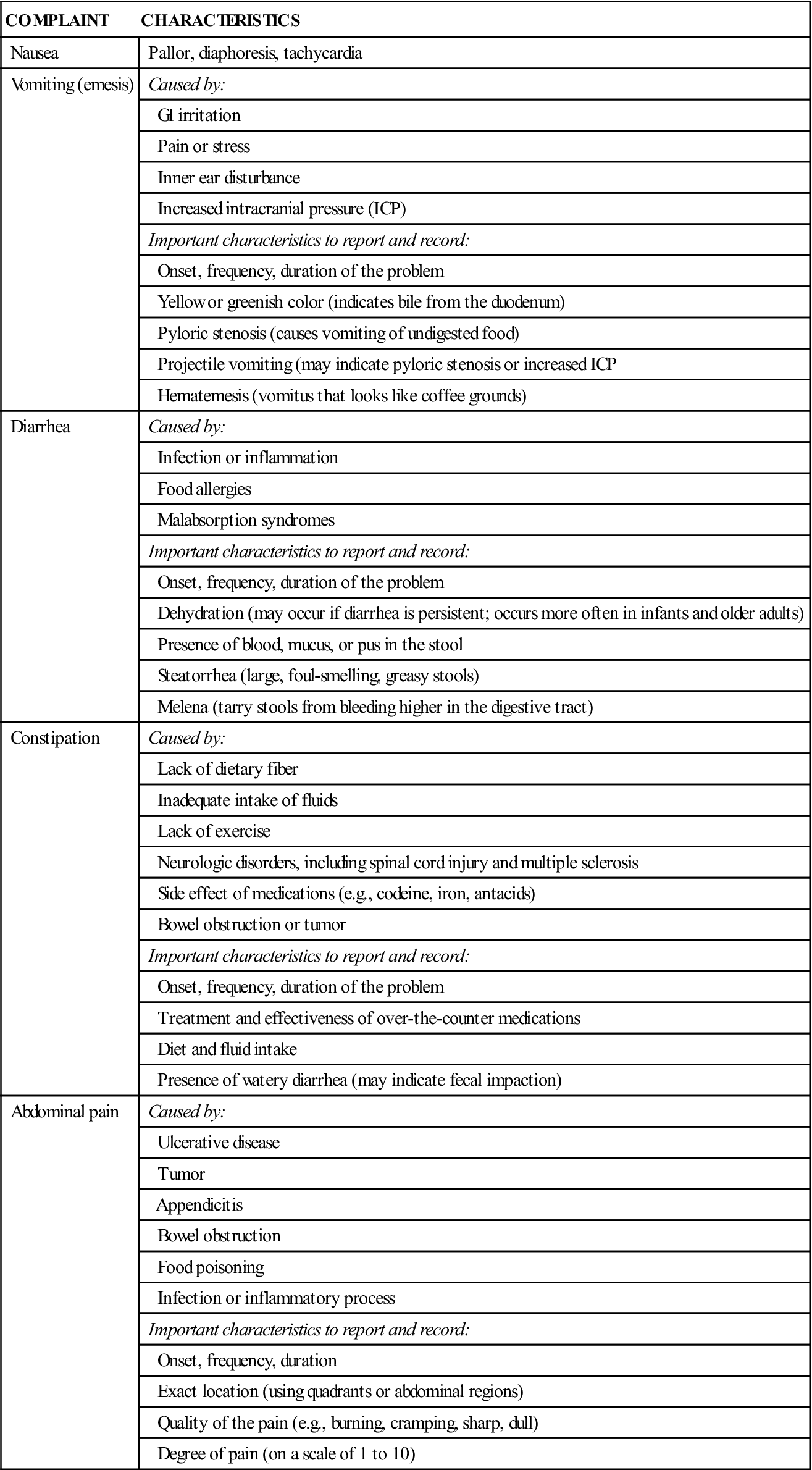

Characteristics of the GI System

COMPLAINT

CHARACTERISTICS

Nausea

Pallor, diaphoresis, tachycardia

Vomiting (emesis)

Caused by:

GI irritation

Pain or stress

Inner ear disturbance

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

Important characteristics to report and record:

Onset, frequency, duration of the problem

Yellow or greenish color (indicates bile from the duodenum)

Pyloric stenosis (causes vomiting of undigested food)

Projectile vomiting (may indicate pyloric stenosis or increased ICP

Hematemesis (vomitus that looks like coffee grounds)

Diarrhea

Caused by:

Infection or inflammation

Food allergies

Malabsorption syndromes

Important characteristics to report and record:

Onset, frequency, duration of the problem

Dehydration (may occur if diarrhea is persistent; occurs more often in infants and older adults)

Presence of blood, mucus, or pus in the stool

Steatorrhea (large, foul-smelling, greasy stools)

Melena (tarry stools from bleeding higher in the digestive tract)

Constipation

Caused by:

Lack of dietary fiber

Inadequate intake of fluids

Lack of exercise

Neurologic disorders, including spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis

Side effect of medications (e.g., codeine, iron, antacids)

Bowel obstruction or tumor

Important characteristics to report and record:

Onset, frequency, duration of the problem

Treatment and effectiveness of over-the-counter medications

Diet and fluid intake

Presence of watery diarrhea (may indicate fecal impaction)

Abdominal pain

Caused by:

Ulcerative disease

Tumor

Appendicitis

Bowel obstruction

Food poisoning

Infection or inflammatory process

Important characteristics to report and record:

Onset, frequency, duration

Exact location (using quadrants or abdominal regions)

Quality of the pain (e.g., burning, cramping, sharp, dull)

Degree of pain (on a scale of 1 to 10)

Cancers of the Gastrointestinal Tract

TUMOR

CHARACTERISTICS

CAUSE OR CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Oral tumor

White mass in or on the mouth that bleeds easily; ulcer or fissure that does not heal; the mass usually is not painful

Cancer of the lip (pipe smoking), cancer of the tongue or gums (chewing tobacco)

Esophageal cancer

Typically found in the distal esophagus; initial sign is dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

Associated with chronic irritation resulting from chronic esophagitis, alcohol abuse, or smoking

Gastric cancer

Asymptomatic in early stages; usually not diagnosed until well advanced; poor prognosis; marked by anorexia, indigestion, weight loss, fatigue; tests positive for occult blood in the stool

Food preservatives, long-term use of nitrates, smoked foods; genetic association; chronic gastritis

Liver cancer

Primary malignant tumors rare, usually a metastasized secondary tumor; initial symptoms mild; anorexia, vomiting, weight loss, fatigue, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, portal hypertension; usually advanced when diagnosed

Primary tumor caused by cirrhosis from hepatitis or chemical exposure

Pancreatic cancer

Weight loss, jaundice; usually advanced when diagnosed; metastasis occurs early; no effective treatment

Cigarette smoking

Colorectal cancer

Usually develops from polyps in the colon; metastasis to the liver common; initial signs depend on location of tumor, may include changes in the character of stool, iron-deficiency anemia, fatigue, weight loss, frank bleeding, or melena

Genetic or familial link; diet high in fat, sugar, and red meat and low in fiber; usually occurs in patients over age 55

Disorders of the Esophagus and Stomach

Hiatal Hernia

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

Assisting in Gastroenterology

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access