1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care. 3. Explain the major functions of the skin. 4. Describe the anatomic structures of the skin. 5. Compare various skin lesions and give examples of each. 6. Describe typical integumentary system infections. 7. Differentiate among various inflammatory and autoimmune integumentary disorders. 8. Recognize thermal injuries to the skin. 9. Compare the characteristics of benign and malignant neoplasms. 10. Explain the grading and staging of malignant tumors. 11. Conduct patient education on the warning signs of cancer. 12. Describe skin malignancies and their treatment. 13. Define the ABCDE rule for identifying a malignant melanoma. 14. Summarize allergy testing procedures. 15. Explain dermatologic procedures performed in the ambulatory care setting. 16. Describe the diagnosis and treatment of allergies. 17. Correctly obtain an exudate sample from a wound for laboratory analysis. 18. Discuss the medical assistant’s role in patient education regarding the integumentary system. alopecia (al-o-pe′-se-uh) Partial or complete lack of hair. bilirubin (bih-luh-roo′-bin) An orange pigment in bile; its accumulation leads to jaundice. cryosurgery The technique of exposing tissue to extreme cold to produce a well-defined area of cell destruction. debridement The removal of foreign material and dead, damaged tissue from a wound. electrodesiccation The destruction of cells and tissue by means of short high-frequency electrical sparks. eschar Devitalized skin that forms a scab or a dry crust over a burn area. exacerbation An increase in the seriousness of a disease, marked by greater intensity of the signs and symptoms. excoriated Skin that has been injured by scratching; abraded. glomerulonephritis (glo-mer′-yoo-loh-nih-fri′-tuhs) Inflammation of the glomerulus of the kidney. hyperplasia An increase in the number of normal cells. keloid A raised, firm scar formation caused by overgrowth of collagen at the site of a skin injury. keratin A very hard, tough protein found in the hair, nails, and epidermal tissue. keratinocytes The skin cells that synthesize keratin. leukoderma Lack of skin pigmentation, especially in patches. opaque Not translucent or transparent; murky. petechiae (peh-te′-ke-uh) Small, purplish hemorrhagic spots on the skin. postherpetic neuralgia Pain that lasts longer than a month after a shingles infection and is caused by damage to the nerve; the pain may last for months or years. Raynaud’s phenomenon Intermittent attacks of ischemia of the extremities, resulting in cyanosis, numbness, tingling, and pain. teratogen (te-rah′-tuh-jen) Any substance that interferes with normal prenatal development, resulting in a developmental abnormality. Dr. Sam Lee is a dermatologist who employs several medical assistants in his busy private practice. Melissa Bauman, CMA (AAMA), has worked for Dr. Lee since graduating from a medical assisting program last year. Melissa works as a clinical specialist, whose primary responsibilities are to perform telephone screening, prepare patients for procedures, and assist Dr. Lee as needed. To fulfill her responsibilities in the dermatology practice, Melissa must be familiar with common diseases and disorders that affect the skin, must assist with dermatologic procedures, and must be prepared to reinforce patient education about the treatment and prevention of dermatologic conditions. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • What is the basic anatomy and physiology of the integumentary system? • What are common diseases and disorders that affect the integumentary system? • How can Melissa determine the difference between the levels of burn injuries? • Why is it important that Melissa understand the concepts of staging and grading of malignant tumors? • What are the primary malignancies of the skin? • What dermatologic procedures should Melissa be prepared to perform? The skin is the largest organ of the human body. In an average-size adult, it covers a total area of about 20 square feet. Forming the outer boundary of the body, the skin performs several essential functions: it acts as a barrier to protect vital internal organs from infection and injury; it helps dissipate heat and regulate body temperature; and it synthesizes vitamin D when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. In addition, various sensory receptors present throughout the skin enable it to respond to such sensations as heat, cold, pain, and pressure. The specialty of dermatology deals with the skin and its accessory structures—hair, nails, and sweat glands, and the subcutaneous tissue that lies beneath the skin. A physician who specializes in dermatology is called a dermatologist. The integumentary system is composed of the skin and its accessory organs. Each square inch of the skin contains millions of cells, numerous specialized nerve endings, hair follicles, muscles, sweat glands to cool the body, and sebaceous glands, which release sebum, an oily substance that lubricates the skin. These diverse structures and glands are nourished by a permeating, elaborate network of blood vessels. The thickness of human skin varies markedly at different parts of the body, ranging from fairly thin over protected areas, such as the eyelids, to very thick over areas subject to abrasion, such as the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. Skin is composed of three layers: the epidermis—the thin, uppermost layer; the dermis—the thicker layer beneath that makes up about 90% of the skin mass and often is referred to as the true skin; and the subcutaneous layer—the layer composed primarily of fatty, or adipose, tissue (Figure 38-1). New skin cells, called keratinocytes, are found in the basal cell layer of the epidermis and migrate upward over about 4 weeks. As the cells move toward the surface, they grow flatter and scalier, eventually losing their nuclei and changing into dead skin cells that contain an inert protein called keratin. Keratin makes up the outermost layer of the epidermis and forms a protective barrier across the surface of the skin that helps control water loss from the body. Ultimately, the outermost keratin layer sloughs off as a result of washing and friction. Hair and nails, which are also composed of keratin, are products of the epidermis. About 95% of the cells in the epidermis are keratinocytes. The other 5% of epidermal cells are pigmented cells, or melanocytes. Melanin is a protein manufactured in the body that gives coloring to the skin and protects the body from UV radiation. Skin coloring is determined not by the total number of melanocytes, which is relatively constant for all races, but rather by the rate at which these cells produce melanin. The amount of melanin produced depends on genetics and exposure to UV light. Individuals with albinism, an inherited recessive trait, are unable to produce melanin, so they have white hair and skin and lack pigment in the iris. Because they have no protection from UV light, they must stay out of the sun. The underlying dermis is a thick layer of connective tissue that contains collagen and elastin fibers, as well as water and jellylike materials that make the skin compressible. Collagen fibers help prevent tearing of the skin, and elastin is a flexible fiber that makes the skin resilient. Distributed throughout the dermis are blood vessels, lymph vessels, muscle cells, hair follicles, and sebaceous and sweat glands. The two types of sweat glands are exocrine glands, which excrete sweat through skin pores to release heat or create sweat in response to stress, and apocrine glands, which open into hair follicles and are located in specific areas, including the axilla, scalp, face, and genitalia. Sweat is odorless when excreted; bacterial action results in odor. A variety of microorganisms, called normal or resident flora, are found on the skin and may increase the risk of integumentary system infection. Healthcare workers are encouraged to sanitize their hands before and after each procedure to prevent transient microbes picked up throughout the day from becoming resident flora. If transient microorganisms are not destroyed and/or removed by good hand sanitization techniques, they eventually become part of the individual’s resident flora. Sensory receptors for the nervous system that detect pain, temperature, pressure, or texture also are located in the dermis. The subcutaneous layer contains fat cells, which provide insulation and serve as a depository for reserve calories. It also contains blood vessels, nerves, and the base of the appendages of the skin. Subcutaneous tissue is distributed unevenly, and as the human body ages, it thins considerably, which can make administering injections or drawing blood more difficult in aging patients. This loss of subcutaneous tissue is one reason elderly people are unable to compensate for changes in temperature, so they are colder when temperatures drop and hotter when temperatures rise. Aging skin is very fragile; it is easily traumatized and damaged by items such as the tourniquets used for drawing blood and bandage adhesives. The medical assistant must be very careful to avoid injuring the skin of an elderly person. Skin is continuously exposed to the environment and may be affected by a wide range of disorders, including infections, inflammatory processes, allergic reactions, and tumors. Many skin problems resolve spontaneously, others can be managed with drug therapy, and still others, such as tumors, large cysts, or moles, may require surgical intervention. Skin lesions can be caused by a systemic problem, such as an allergic reaction to medication, or they may develop from a localized infection. When communicating with the physician, documenting in the patient’s chart, or doing telephone screening, always use correct medical terminology to describe skin lesions, such as, “The patient reports a widespread maculopapular rash across the anterior trunk” rather than, “The patient has a red raised rash on his stomach.” When you gather details from the patient about the characteristics of lesions, some questions you should consider include the following: • Describe the color, elevation, and texture of the lesion. • Is there any pain or pruritus (itching)? If pruritus is present, is the area excoriated or inflamed? • Is there any drainage? If so, what are its characteristics? • What is the exact anatomic location of the lesion? Have there been changes over time? Primary lesions are those that appear immediately. Macules, papules, plaques, nodules, cysts, wheals, and pustules all are primary lesions. Secondary lesions are the result of alterations in a primary lesion. Examples of secondary lesions include scales, crusts, fissures, erosions, ulcerations, and scars (Figure 38-2). For instance, vesicles from a partial-thickness burn are primary lesions, but if the blisters break and ulcerations form, healing ends in a scar. Ulcerations and scars are secondary lesions. Impetigo is a common, superficial infection caused by streptococci or Staphylococcus aureus that usually affects children. Initially, impetigo looks like small vesicles on the face, especially around the nose and mouth, which quickly enlarge and rupture, excreting a honey-colored exudate. The exudate forms crusty lesions, and beneath the crust, the area is inflamed and moist (Figure 38-3). Pruritus accompanies the infection, and scratching helps spread the lesions at the site. Impetigo is contagious, and bacteria are transmitted by direct contact with the drainage, whether at other sites or with other children through the sharing of toys and touching. Consistent hand washing is required to help break the chain of infection. It also is important to keep personal items that may be contaminated, such as washcloths, linens, and drinking glasses, away from other members of the family. If the areas of infection are limited, topical treatment with an antibiotic ointment may be effective. However, impetigo caused by streptococci may result in glomerulonephritis; more involved infections may require treatment with oral antibiotics. Acne vulgaris typically begins at puberty and is caused by a number of factors, including inherited predisposition, hormonal fluctuations, exposure to heat and humidity, and the use of oily creams (Figure 38-4). Acne is a disorder of the hair follicle and sebaceous gland unit. It develops when sebum, which reaches the skin surface through the hair follicles, stimulates the follicle walls, causing more rapid shedding of skin cells. Cells and sebum stick together and form a plug that promotes the growth of staphylococcal organisms in the follicles. The result is the formation of comedones (blackheads), pimples, pustules, or larger abscesses at the site. Acne treatment begins with twice-daily face washes with benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid. Medications include topical antibiotic cream such as erythromycin or application of a retinoid such as Retin-A (tretinoin) or adapalene (Differin). Oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline and doxycycline, at a maintenance dose of 250 mg once or twice daily, can be prescribed to control comedones and pustules. Severe cystic acne can be treated with isotretinoin (Accutane or Sotret), but this drug is a strong teratogen and should never be prescribed for pregnant women or women who are not using contraceptives. The use of oral contraceptives, such as Ortho Tri-Cyclen, and Yaz, may reduce acne outbreaks as well. Laser resurfacing can be performed to smooth out shallow acne scars that form as the result of extreme cases of acne vulgaris. Acne conglobata is a severe form of acne that typically occurs later in life and results in lesions across the back, buttocks, thighs, face, and chest. Abscesses or cysts may form between affected sites, and healing frequently results in keloid formation. This type of acne requires more aggressive treatment with systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), oral antibiotics, oral retinols (Accutane), and laser resurfacing or debridement to treat excessive scarring. Rosacea is a chronic disease seen most frequently in women between the ages of 30 and 60. It causes inflammation and pustule formation and begins as frequent flushing across the nose, forehead, cheeks, and chin. As the condition progresses, capillaries of the face dilate and are visible across affected areas as small, red, edematous lines; these are accompanied by eye inflammation and photosensitivity. Over time, the face appears red, eye inflammation is more apparent, and painful nodules and pustules form. Men with rosacea may develop rhinophyma, a large, inflamed, bulbous nose caused by hyperplasia of sebaceous nasal tissue (Figure 38-5). Individuals with rosacea eventually may develop an obvious thickening of the skin across the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin. The condition is treated with topical antibiotics and, as symptoms progress, with oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline, erythromycin, or doxycycline. Antibiotics help treat the pustule formation but do not affect the redness and flushing, which may cause the patient greatest concern. A furuncle, or boil, is a localized staphylococcal infection that begins as an inflammation of a hair follicle (folliculitis) or a skin gland. The affected area is raised, inflamed, and painful and eventually may produce purulent drainage. A carbuncle is a collection of furuncles that have joined to form a large infected area that may drain through multiple sites or form an abscess. Both infections are treated with oral antibiotics, frequent cleansing of the area, application of an antibiotic ointment, and, in some cases, surgical incision and drainage of the purulent material. Cellulitis, also called erysipelas, is an acute infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by staphylococci or streptococci. It begins from a small cut or as a result of a skin injury, or it develops at the site of a furuncle or ulcer. The area surrounding the site becomes inflamed, edematous, and painful with red streaks along the lymph vessels that lead from the infection. The condition is treated with oral antibiotics. Warm compresses applied locally aid healing, and analgesics may be needed to relieve discomfort. Cellulitis must be treated with caution, because a systemic infection can develop if the lymph glands become involved. Fungal, or mycotic, infections such as tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) (Figure 38-6, A), tinea cruris (jock itch) (Figure 38-6, B), and tinea corporis (ringworm) (Figure 38-6, C) are extremely common. These pathogens, which tend to live off dead tissue in the keratin layer of the epidermis, the hair, or the nails, cause almost no inflammation in the underlying skin. The fungus invades the skin, where it has been damaged or is consistently moist. All of these lesions are pruritic and are characterized by a distinct border with scaling areas that have a clear center. Secondary bacterial infections may occur with excoriation. The physician typically diagnoses a fungal infection by noting the way the skin looks and the patient’s complaints of pruritus. The skin may be scraped to obtain cells for examination under a microscope, and sometimes the physician may order a skin culture, for which a suspicious area is swabbed or scraped using sterile technique and the sample is sent to the laboratory for analysis. Treatment consists of topical antifungal agents, such as clotrimazole (Lotrimin), ketoconazole (Nizoral), econazole (Spectazole), or nystatin (Mycostatin). Antibiotics may be necessary if a secondary infection occurs. Because mycotic infections thrive in dark, moist areas, the patient should be advised to keep the site clean and dry and to wear loose clothing if possible. All types of dermatophytoses can become chronic infections if not managed carefully. Tinea unguium, or onychomycosis, is a fungal infection of the toenails and fingernails. Unlike athlete’s foot, which occurs on the skin’s surface, nail fungus lives in the nail bed and the nail plate. The nail provides the fungus with an extremely well-protected place to live, which is why nail fungus may be especially difficult to treat. The primary sign of nail fungus is the appearance of the nail, which turns yellow, white, or opaque (Figure 38-7). The texture also changes, and the nail becomes thick and brittle. If the fungus has been present for a long time, the nail can become twisted or distorted. The most effective treatment for nail fungus is oral terbinafine hydrochloride (Lamisil), which inhibits the production of fungal cells. However, the drug must be taken for 6 weeks to treat fungal infection of a fingernail and for 12 weeks for infection of a toenail; treatment carries the risk of liver complications. Warts, or verrucae, are caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV). Infection with HPV results in hyperplasia of the epidermis and a raised, cauliflower-like appearance. Verrucae can develop anywhere, but the most common sites are the fingers and the soles of the feet (plantar warts). (Genital warts are addressed in Chapter 40.) Most warts resolve over time, but they can be treated with topical chemicals, excised surgically, vaporized with lasers, or removed with cryosurgery. Cold sores or fever blisters are caused by the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). The initial infection may be asymptomatic or may cause painful ulcers along the gumlines of the mouth or on the lips. After the primary infection, the virus remains dormant in the trigeminal nerve and can be reactivated by exposure to the sun or to cold; by the presence of another infection, such as an upper respiratory infection; or when the patient is under stress. The patient reports a feeling of burning, tingling, or numbness before the eruption of vesicles. The blisters heal in 2 to 3 weeks, but the process may be speeded up by the use of topical antiviral drugs, such as acyclovir (Zovirax) or penciclovir cream (Denavir), or with oral antivirals, including Zovirax or valacyclovir (Valtrex). If applied at the first indications of a cold sore, the topical antiviral creams can limit the duration and severity of the outbreak. Herpes zoster is an acute inflammatory disorder characterized by highly painful vesicular eruptions on the trunk of the body and occasionally on the face (Figure 38-8). The lesions develop on one side of the body and follow the course of the peripheral nerve, or dermatome, which has been infected by the varicella virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox. If the virus is not completely destroyed by the immune system, it lies dormant in dorsal root ganglia and is reactivated in later years. The cause of this reactivation is unclear, although it appears to be related to stress, immune system problems, and aging. The onset of the disorder usually is marked by pain along the nerve pathway, and lesions appear in approximately 3 days. Inflammation lasts 10 days to 5 weeks. The patient is diagnosed by the characteristic pattern of painful lesions, and the diagnosis may be confirmed by isolating the virus in cell cultures. The condition also can be detected by the presence of varicella zoster antibodies in the blood. Treatment focuses on promoting patient comfort with analgesic and antipruritic medications. Corticosteroid medications (prednisone) and antiviral drugs, including topical or oral acyclovir (Zovirax) and oral famciclovir (Famvir) or valacyclovir (Valtrex), also can be prescribed. One of the most serious complications of herpes zoster is postherpetic neuralgia, which causes chronic pain after resolution of the initial outbreak and may require treatment with a combination of medications, including topical calamine (Caladryl) lotion, capsaicin cream (Zostrix), topical lidocaine (Xylocaine), narcotics, a tricyclic antidepressant (e.g., Elavil, Tofranil), and anticonvulsants (including Dilantin, Tegretol, and Neurontin). Two vaccines are available that may help prevent shingles. The chickenpox (varicella virus) vaccine (Varivax) is given to babies 12 to 18 months old and to older children and adults who have not had the chickenpox; this vaccine reduces the risk and severity of both chickenpox and shingles. A new varicella-zoster vaccine (Zostavax) is recommended for all adults over age 60, regardless of whether they have had shingles. This vaccine does not guarantee protection against shingles, but it can reduce the duration and severity of the outbreak, and it helps prevent postherpetic neuralgia. The itch mite (which causes scabies) and lice (which cause pediculosis) are the two most common parasites that infest human beings. Scabies mites are tiny organisms, barely visible to the eye, that burrow into the epidermis (Figure 38-9). Pediculosis can be caused by three different types of lice: head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis; Figure 38-10, A), body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis), and pubic lice (Pthirus pubis; Figure 38-10, B). Both scabies and lice infestations are highly contagious. The diagnosis of scabies may require scraping the skin at an inflamed area and examining the mites under a low-power microscope. Lice can be seen on the hair shafts. Patients describe symptoms of intense itching, possibly a body rash, and a sensation of something crawling on the skin. Treatment consists of ridding the body of the parasite, controlling the pruritus, and disinfecting the home environment to prevent reinfestation.

Assisting in Dermatology

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

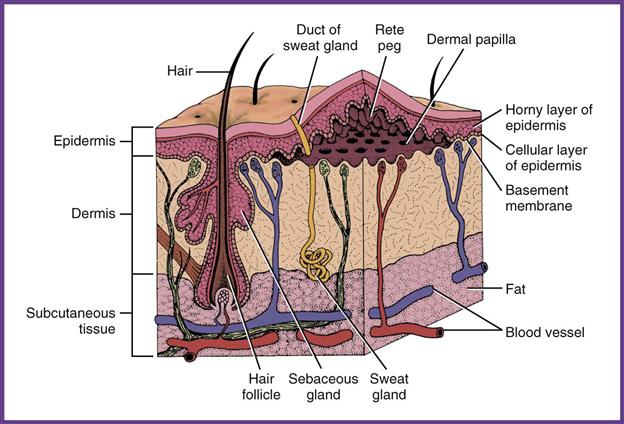

Anatomy and Physiology

Epidermis

Dermis

Subcutaneous Layer

Diseases and Disorders

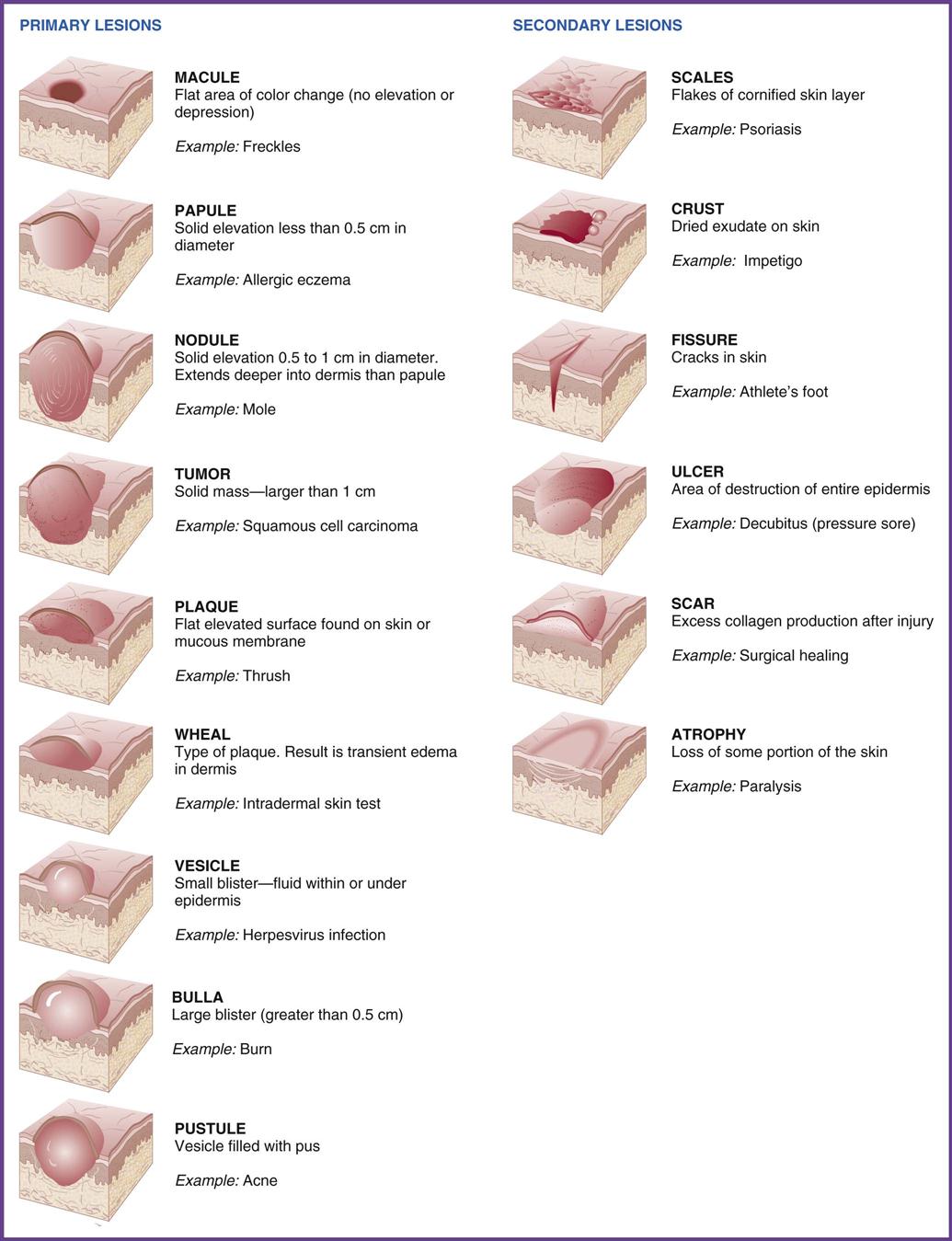

Skin Lesions

Infections

Bacterial Infections

Impetigo.

Acne.

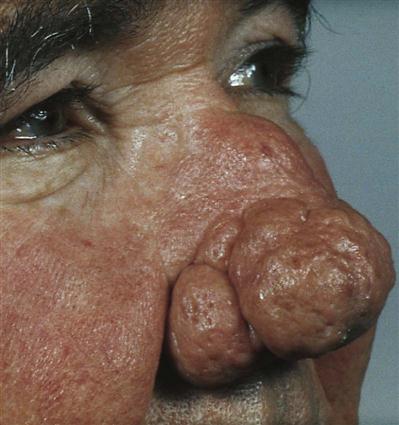

Rosacea.

Furuncles and Carbuncles.

Cellulitis.

Fungal Infections (Dermatophytoses)

Viral Infections

Warts.

Herpes Simplex (Cold Sores).

Herpes Zoster (Shingles).

Other Infections

Scabies and Pediculosis.

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access