Assessment of Psychiatric–Mental Health Clients

The first step in the nursing process, the assessment of the client, is crucial. Assess the client in a holistic way, integrating any relevant information about the client’s life, behavior, and feelings. The focus of care, beginning with the initial assessment, is toward the client’s optimum level of health and independence from the hospital.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Define the nursing process.

Articulate the purpose of a comprehensive nursing assessment.

Differentiate the purpose of a focused and a screening assessment.

Explain the significance of cultural competence during the assessment process.

Recognize how disturbances in communication exhibited by a client can impair the assessment process.

Describe the importance of differentiating among the six types of delusions during the assessment process.

Interpret the five types of hallucinations identified in psychiatric disorders.

Recognize the differences between obsessions and compulsions.

Determine levels of orientation and consciousness during the assessment process.

Reflect on how information obtained during the assessment process is transmitted to members of the health care team.

Formulate the criteria for documentation of assessment data.

Key Terms

Acute insomnia

Affect

Blocking

Circumstantiality

Clang association

Compulsions

Delusions

Depersonalization

Echolalia

Flight of ideas

Hallucinations

Illusion

Insight

Insomnia

Looseness of association

Memory

Mood

Mutism

Neologism

Neurovegetative changes

Obsessions

Perseveration

Primary insomnia

Secondary insomnia

Tangentiality

Verbigeration

Word salad

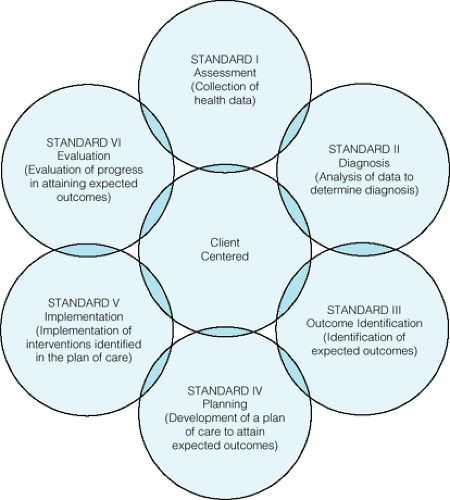

The nursing process is a six-step problem-solving approach to nursing that also serves as an organizational framework for the practice of nursing (Fig. 9-1). It sets the practice of nursing in motion and serves as a monitor of quality nursing care. Nurses in all specialties practice the first step, assessment. This chapter focuses specifically on the assessment of clients with psychiatric disorders, including those clients who may have a coexisting medical diagnosis.

Client Assessment

The assessment phase of the nursing process includes the collection of data about a person (child, adolescent, adult, or older adult client), family, or group by the methods of observing, examining, and interviewing. The type of assessment that occurs depends on the client’s needs, presenting symptoms, and clinical setting. For example, an adolescent client who attempts suicide may be assessed in the emergency room, or an older adult may be assessed in a nursing home to rule out the presence of major depression secondary to a cerebral vascular accident.

Two types of data are collected: objective and subjective. Objective data include information to determine the client’s physical alterations, limits, and assets (Nettina, 2001). Objective data are tangible and measurable data collected during a physical examination by inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Objective data can also include observable client behavior such as crying or talking out loud when no one else is in the room. Laboratory results and vital signs also are examples of objective data. Subjective data are obtained as the client, family members, or significant others provide information spontaneously during direct questioning or during the health history. It can also include any statements made by the client, for example, “I hate my life and I want to die.” Subjective data also are collected during the review of past medical and psychiatric records. This type of data collection involves interpretation of information by the nurse.

Types of Assessment

Three kinds of assessment exist: comprehensive, focused, and screening assessments. A comprehensive assessment includes data related to the client’s biologic, psychological, cultural, spiritual, and social needs. This type of assessment is generally completed in collaboration with other health care professionals such as a physician, psychologist, neurologist, and social worker. A physical examination is performed to rule out any physiologic causes of disorders such as anxiety, depression, or dementia. For example, more than 30% of clients with dermatologic diseases have reported the presence of depressive and anxiety disorders. Neuroimaging has been included as part of a comprehensive assessment to avoid misdiagnosis or a serious delay in the diagnosis of some psychiatric disorders. It has been used to confirm psychiatric diagnoses in clients who exhibited auditory hallucinations, symptoms of bipolar disorder, behavioral symptoms of acute onset dementia, and atypical headache symptoms (Johnson, 2005; Novick, 2004; Romano, 2004; Wright, 2005). Many psychiatric facilities require a comprehensive assessment, including medical clearance, before or within 24 hours of admission to avoid medical emergencies in the psychiatric setting.

A focused assessment includes the collection of specific data regarding a particular problem as determined by the client, a family member, or a crisis situation. For example, in the event of a suicide attempt, the nurse would assess the client’s mood, affect, and

behavior. Data regarding the attempted suicide and any previous attempts of self-destructive behavior would also be collected (see Chapter 31).

behavior. Data regarding the attempted suicide and any previous attempts of self-destructive behavior would also be collected (see Chapter 31).

A screening assessment includes the use of assessment or rating scales to evaluate data regarding a specific problem or behavior. Although a client’s history may remain stable, his or her mental status or behavior can change from day to day or hour to hour. The psychiatric mental status examination is one type of screening assessment that can be used in a variety of locations such as the emergency room, the physician’s office, or an outpatient clinic. This assessment provides a description of the client’s appearance, speech, mood, thinking, perceptions, sensorium, insight, and judgment (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Other examples of screening assessments or rating scales used to evaluate data regarding a particular problem or behavior include the Folstein Mini Mental State Examination, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Dementia Rating Scale, Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI-10), Impulsivity Scale, or the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD).

Although rating scales provide useful symptom frequency and severity data, client reliability and credibility are reasonable concerns. However, the rating scales can provide objective information about clients in a variety of situations and help confirm the diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (Menaster, 2004). For example, a screening assessment using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale could be utilized to evaluate the frequency and severity of a client’s movement disorder during administration of neuroleptic medication to stabilize clinical symptoms of schizophrenia.

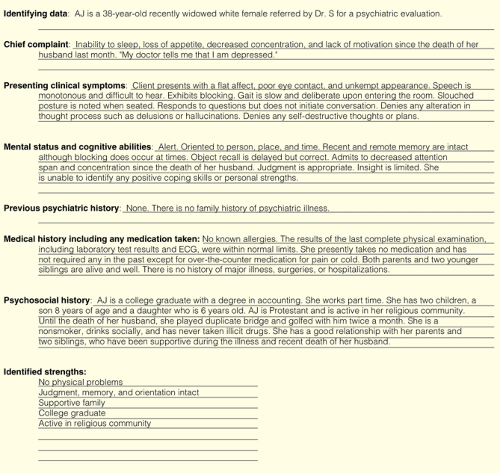

During any assessment, the psychiatric–mental health nurse uses a psychosocial nursing history and assessment tool to obtain factual information, observe client appearance and behavior, and evaluate the client’s mental or cognitive status. A sample psychosocial nursing history and assessment form is shown in Figure 9-2. Examples of assessment tools or screening instruments used to diagnose specific psychiatric disorders are discussed in the appropriate chapters of Units VI and VII.

Cultural Competence During Assessment

According to the 2000 census, more than 6.8 million Americans identified themselves as multiracial such as

white/other, white/Native American, white/Asian, white/black, Asian/other, black/other, and three or more races. Cultural competence experts realize that nurses cannot learn the customs, languages, and specific beliefs of every client they see. But the psychiatric–mental health nurse must possess sensitivity, knowledge, and skills to provide care to culturally diverse groups of clients to avoid labeling persons as noncompliant, resistant to care, or abnormal. For example, the act of suicide is accepted in some cultures as a means to escape identifiable stressors such as marital discord, illness, criticism from others, and loneliness (Andrews & Boyle, 2003).

white/other, white/Native American, white/Asian, white/black, Asian/other, black/other, and three or more races. Cultural competence experts realize that nurses cannot learn the customs, languages, and specific beliefs of every client they see. But the psychiatric–mental health nurse must possess sensitivity, knowledge, and skills to provide care to culturally diverse groups of clients to avoid labeling persons as noncompliant, resistant to care, or abnormal. For example, the act of suicide is accepted in some cultures as a means to escape identifiable stressors such as marital discord, illness, criticism from others, and loneliness (Andrews & Boyle, 2003).

Several client cultural assessment approaches, identified by Mackey-Padilla (2005) and Kanigel (1999), can be used during the assessment and treatment of diverse client populations. These approaches are:

Assess and clarify the client’s cultural values, beliefs, and norms.

Assess the client’s degree of cultural assimilation/acculturation.

Assess the client’s perspective regarding feelings and symptoms. Questions would include “What do you call your illness?,” “What do you think causes it?,” and “How have you treated it?”

Elicit the client’s expectations and ask what the client feels is important for the health care provider to know about the client’s biopsychosocial needs. Negotiate treatment. Explain what assessment tools may be used. Ask the client whether there is a need to clarify any information as the assessment process occurs.

Learn how to work with interpreters. Using a family member as an interpreter is contraindicated because a family member may omit data or give erroneous information. (According to the recent Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPAA] privacy rules policy, the client must give permission to include a family member or an interpreter in the interview; otherwise a breach of client confidentiality could occur.)

When using an interpreter, talk to the client rather than the interpreter. Observe the client’s eyes and face for nonverbal reactions.

Seek collaboration with bilingual community resources, such as a social worker, for assistance in meeting biopsychosocial needs of clients who have difficulty communicating in a second language.

Talking openly and communicating with the client can provide valuable information about compliance and behavior. Acknowledging that differences do exist is the most important thing that the psychiatric–mental health nurse can do. Refer to Chapter 4 for more detailed information about cultural competence of the psychiatric–mental health nurse.

Collection of Data

Many data are collected by the psychiatric–mental health nurse during a comprehensive assessment, which may take place in a variety of settings such as the primary care setting, general hospital, or psychiatric clinical setting. Specific questions or guidelines are at times included in the assessment to alert the nurse to information that could be overlooked or misinterpreted. Clients are often reluctant to discuss their mental or emotional problems because of the stigma that mental illness has historically carried. They may not have the self-awareness to realize that their emotional symptoms may play a role in their physical and general well-being.

Appearance

General appearance includes physical characteristics, apparent age, peculiarity of dress, cleanliness, and use of cosmetics. A client’s general appearance, including facial expressions, is a manner of nonverbal communication in which emotions, feelings, and moods are related. For example, people who are depressed often neglect their personal appearance, appear disheveled, and wear drab-looking clothes that are generally dark in color, reflecting a depressed mood. The facial expression may appear sad, worried, tense, frightened, or distraught. Clients with mania may dress in bizarre or overly colorful outfits, wear heavy layers of cosmetics, and don several pieces of jewelry.

Affect, or Emotional State

Affect is defined as an individual’s present emotional responsiveness. It is the observable manifestation of one’s emotions or feelings inferred from facial expressions (eg, anger, sadness, or happiness). For example, when complemented by his teacher a child smiles. He is expressing an affective or emotional response to the complement. (The terms affect and emotion are commonly used interchangeably.) Mood is a descriptive term that refers to the presence of pervasive and sustained

emotions or feelings described by a person (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Shahrokh & Hales, 2003). For example, a woman who cries frequently and says she misses her deceased husband who died last month, is exhibiting a depressed mood. The relationship between one’s affect and mood is of particular significance. The term congruent is used to describe consistency between a person’s affect and mood (eg, “The client’s affect is congruent with his mood.”). Conversely, affect can be widely divergent or incongruent from what one says or does. For example, a client may appear happy in the presence of family members but, when alone, abuses alcohol in an attempt to alleviate a depressed mood. Apathy is a term that may be used to describe an individual’s display of lack of emotion, interest, or concern.

emotions or feelings described by a person (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Shahrokh & Hales, 2003). For example, a woman who cries frequently and says she misses her deceased husband who died last month, is exhibiting a depressed mood. The relationship between one’s affect and mood is of particular significance. The term congruent is used to describe consistency between a person’s affect and mood (eg, “The client’s affect is congruent with his mood.”). Conversely, affect can be widely divergent or incongruent from what one says or does. For example, a client may appear happy in the presence of family members but, when alone, abuses alcohol in an attempt to alleviate a depressed mood. Apathy is a term that may be used to describe an individual’s display of lack of emotion, interest, or concern.

A lead question such as “What are you feeling?” may elicit such responses as “nervous,” “angry,” “frustrated,” “depressed,” or “confused.” Ask the person to describe the nervousness, anger, frustration, depression, or confusion. Is the person’s emotional response constant or does it fluctuate during the assessment? When performing the interview, always record a verbatim reply to questions concerning the client’s mood and note whether an intense emotional response accompanies the discussion of specific topics. Affective responses may be appropriate, inappropriate, labile, blunted, restricted or constricted, or flat. An emotional response out of proportion to a situation is considered inappropriate. The lack of an affective response to a very emotional event may also be considered inappropriate, such as no display of emotion when discussing a close relative’s death or when discussing another traumatic event. Box 9-1 describes the various affective responses.

Under ordinary circumstances, a person’s affect varies according to the situation or subject under discussion. The person with emotional conflict may have a persistent emotional reaction based on this conflict. As the examiner or observer, identify the abnormal emotional reaction and explore its depth, intensity, and persistence. Such an inquiry could prevent a person who is depressed from attempting suicide.

Behavior, Attitude, and Coping Patterns

Asking about suicidal risk, violent behavior, or substance abuse during client assessments is embarrassing for many nurses. Such embarrassment may result in the nurse’s judging a client or making assumptions about the client (Blair, 2005). To avoid such mistakes when assessing clients’ behavior and attitude, consider the following factors:

Do they exhibit strange, threatening, suicidal, self-injurious, or violent behavior? Aggressive behavior may be displayed verbally or physically against self, objects, or other people. Are they making an effort to control their emotions?

Is there evidence of any unusual mannerisms or motor activity, such as grimacing, tremors, tics, impaired gait, psychomotor retardation, or agitation? Do they pace excessively?

Do they appear friendly, embarrassed, evasive, fearful, resentful, angry, negativistic, or impulsive? Their attitude toward the interviewer or other helping persons can facilitate or impair the assessment process.

Is behavior overactive or underactive? Is it purposeful, disorganized, or stereotyped? Are reactions fairly consistent?

Box 9.1: Types of Affective Responses

Blunted affect: Severe reduction or limitation in the intensity of a one’s affective responses to a situation

Flat affect: Absence or near absence of any signs of affective responses, such as an immobile face and monotonous tone of voice when conversing with others

Inappropriate affect: Discordance or lack of harmony between one’s voice and movements with one’s speech or verbalized thoughts

Labile affect: Abnormal fluctuation or variability of one’s expressions, such as repeated, rapid, or abrupt shifts

Restricted or constricted affect: A reduction in one’s expressive range and intensity of affective responses

If clients are in contact with reality and able to respond to such a question, ask them how they normally cope with a serious problem or with high levels

of stress. Responses to this question enable the nurse to assess clients’ present ability to cope and their judgment. Is there a support system in place? Are clients using medication, alcohol, or illicit drugs to cope? Their behavior may be the result of inadequate coping patterns or lack of a support system.

of stress. Responses to this question enable the nurse to assess clients’ present ability to cope and their judgment. Is there a support system in place? Are clients using medication, alcohol, or illicit drugs to cope? Their behavior may be the result of inadequate coping patterns or lack of a support system.

Clients experiencing paranoia or suspicion may isolate themselves, appear evasive during a conversation, and demonstrate a negativistic attitude toward the nursing staff. Such activity is an attempt to protect oneself by maintaining control of a stressful environment.

Communication and Social Skills

“The manner in which the client talks enables us to appreciate difficulties with his thought processes. It is desirable to obtain a verbatim sample of the stream of speech to illustrate psychopathologic disturbances” (Small, 1980, p. 8).

The client may hesitate to communicate with a complete stranger on the first meeting unless the nurse is able to display empathy for the client’s distress and establish trust with the client. Consider the following factors while assessing clients’ ability to communicate and interact socially:

Do they speak coherently? Does the flow of speech seem natural and logical, or is it illogical, vague, and loosely organized? Do they enunciate clearly?

Is the rate of speech slow, retarded, or rapid? Do they fail to speak at all? Do they respond only when questioned?

Do clients whisper or speak softly, or do they speak loudly or shout?

Is there a delay in answers or responses, or do clients break off their conversation in the middle of a sentence and refuse to talk further?

Do they repeat certain words and phrases over and over?

Do they make up new words that have no meaning to other people?

Is their language obscene?

Does their conversation jump from one topic to another?

Do they stutter, lisp, or regress in their speech?

Do they exhibit any unusual personality traits or characteristics that may interfere with their ability to socialize with others or adapt to hospitalization? For example, do they associate freely with others, or do they consider themselves “loners”? Do they appear aggressive or domineering during the interview? Do they feel that people like them or reject them? How do they spend their personal time?

With what cultural group or groups do they identify?

A review of data collection enables the nurse to integrate specific purposeful communication techniques during interactions with the client. These techniques are chosen to meet the needs of the client and may be modified based on their effectiveness during the nurse–client interaction (Schultz & Videbeck, 2005).

Impaired Communication

During assessment, clients may demonstrate impaired communication. The following terminology defined by Shahrokh and Hales (2003) and Sadock and Sadock (2003) is commonly used to describe this impaired communication: blocking, circumstantiality, clang association, echolalia, flight of ideas, looseness of association, mutism, neologism, perseveration, tangentiality, verbigeration, and word salad.

Blocking

Blocking refers to a sudden stoppage in the spontaneous flow or stream of thinking or speaking for no apparent external or environmental reason. Blocking may be due to preoccupation, delusional thoughts, or hallucinations. For example, while talking to the nurse, a client states, “My favorite restaurant is Chi-Chi’s. I like it because the atmosphere is so nice and the food is…” Blocking is most often found in clients with schizophrenia experiencing auditory hallucinations.

Circumstantiality

With circumstantiality,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access