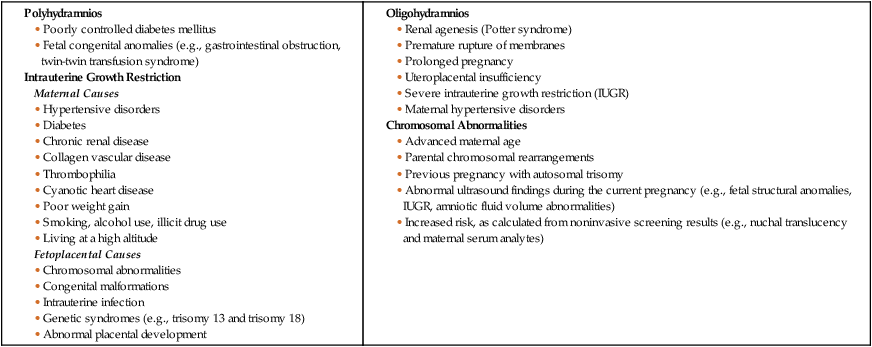

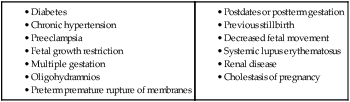

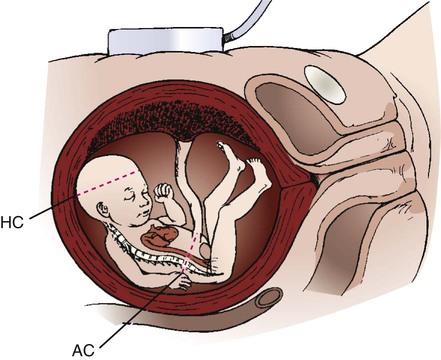

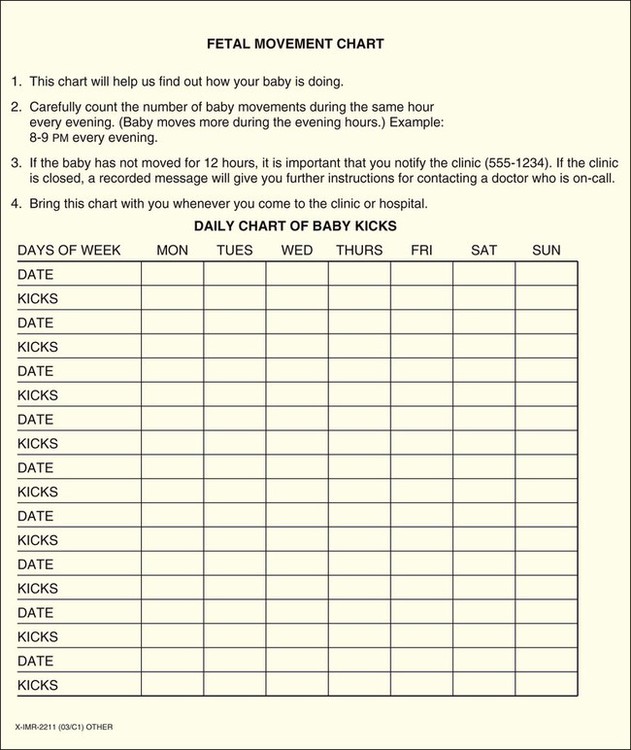

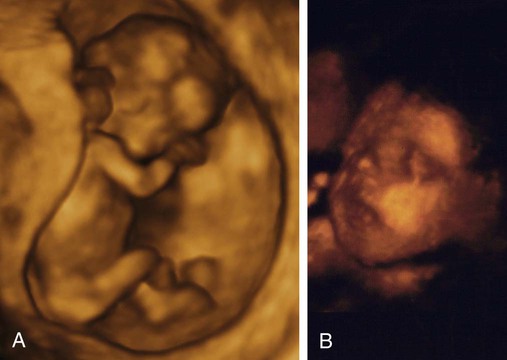

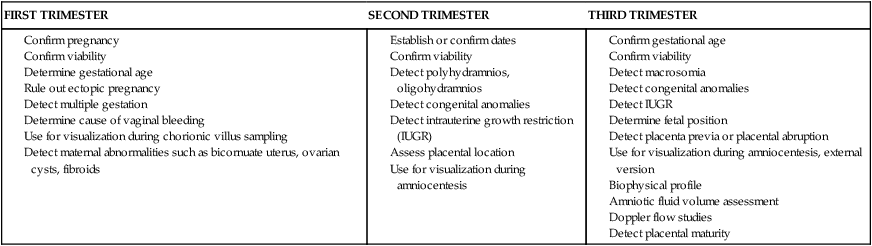

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Explore biophysical, psychosocial, sociodemographic, and environmental influences on high risk pregnancy. • Examine risk factors identified through history, physical examination, and diagnostic techniques. • Discuss psychologic considerations associated with a high risk pregnancy diagnosis. • Differentiate among screening and diagnostic techniques, including when they are used in pregnancy and for what purpose. • Develop a teaching plan to explain screening and diagnostic techniques and implications of findings to women and their families. In 2010, the most recent year for which figures are available, four million births occurred in the United States (Martin, Hamilton, Sutton, et al., 2012). Many of these births were the result of pregnancies considered to be high risk because the life or health of the mother, fetus, or newborn was jeopardized by circumstances coincidental with or unique to the pregnancy. Care of these high risk patients requires the combined efforts of medical and nursing personnel. Factors associated with a diagnosis of a high risk pregnancy are identified in this chapter. Diagnostic techniques often used to monitor the maternal-fetal unit at risk are also described. Pregnancies can be designated as high risk for any of several undesirable outcomes. In the past risk factors were evaluated only from a medical standpoint. Therefore only adverse medical, obstetric, or physiologic conditions were considered to place the woman at risk. Today a more comprehensive approach to high risk pregnancy is used, and the factors associated with high risk childbearing are grouped into broad categories based on threats to health and pregnancy outcome. Categories of risk include biophysical, psychosocial, sociodemographic, and environmental (Box 10-1). Risk factors are interrelated and cumulative in their effects. Biophysical risks include factors that originate within the mother or fetus and affect the development or functioning of either one or both. Examples include genetic disorders, nutritional and general health status, and medical or obstetric-related illnesses. Box 10-2 lists common risk factors for several pregnancy-related problems. Sociodemographic risks arise from the mother and her family. These risks may place the mother and fetus at risk. Examples include lack of prenatal care, low income, marital status, and ethnicity (see Box 10-1). Environmental factors include hazards in the workplace and the woman’s general environment and may include environmental chemicals (e.g., lead, mercury), anesthetic gases, and radiation (Chambers and Weiner, 2009; Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Antepartum testing has two major goals. The first is to identify fetuses at risk for injury caused by acute or chronic interruption of oxygenation so permanent injury or death might be prevented. The second goal is to identify appropriately oxygenated fetuses so unnecessary intervention can be avoided (Miller, Miller, and Tucker, 2013). In most cases monitoring begins by 32 to 34 weeks of gestation and continues regularly until birth. Assessment tests should be selected on the basis of their effectiveness, and the results must be interpreted in light of the complete clinical picture. Box 10-3 lists common maternal and fetal indications for antepartum testing that are supported by currently available evidence (Miller, Miller, and Tucker, 2013). Assessment of fetal activity by the mother is a simple yet valuable method for monitoring the condition of the fetus. The daily fetal movement count (DFMC) (also called kick count) can be assessed at home and is noninvasive, inexpensive, and simple to understand and usually does not interfere with a daily routine. It is frequently used to monitor the fetus in pregnancies complicated by conditions that may affect fetal oxygenation (see Box 10-2). The presence of movements is generally a reassuring sign of fetal health. During the third trimester the fetus makes about 30 gross body movements each hour. The mother is able to recognize 70% to 80% of these movements (Greenberg, Druzin, and Gabbe, 2012). Several different protocols are used for counting. One recommendation is to count once a day for 60 minutes (Fig. 10-1). Fig. 10-1 is an example of a form used to record fetal kick counts. Other common recommendations are that mothers count fetal activity 2 or 3 times daily (e.g., after meals or before bedtime) for 2 hours or until 10 movements are counted or all fetal movements in a 12-hour period each day until a minimum of 10 movements are counted. Except for establishing a very low number of daily fetal movements or a trend toward decreased motion, the clinical value of the absolute number of fetal movements has not been established, other than in the situation in which fetal movements cease entirely for 12 hours (the so-called fetal alarm signal). A count of fewer than three fetal movements within 1 hour warrants further evaluation by a nonstress test or a contraction stress test and a complete or modified biophysical profile (see later discussion). Women should be taught the significance of the presence or absence of fetal movements, the procedure for counting that is to be used, how to record findings on a daily fetal movement record, and when to notify the health care provider. Diagnostic ultrasonography is an important, safe technique in antepartum fetal surveillance. It is considered by many to be the most valuable diagnostic tool used in obstetrics (Richards, 2012). It provides critical information to health care providers regarding fetal activity and gestational age, normal versus abnormal fetal growth curves, fetal and placental anatomy, fetal well-being, and visual assistance with which invasive tests can be performed more safely (Richards, 2012; Simpson, Richards, Otano, et al., 2012). An ultrasound examination can be performed either abdominally or transvaginally during pregnancy. Ultrasound scans produce a two- or three-dimensional view of the area being examined and can be used to create pictorial images (Fig. 10-2, A and B). Box 10-4 explains the differences in these scans and the views they produce. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2009) described three levels of ultrasonography. The standard (also called basic) examination is used most frequently and can be performed by ultrasonographers or other health care professionals, including nurses, who have had special training. Indications for standard ultrasonography are described in detail in the next section. In the second and third trimesters a standard ultrasound examination is used to evaluate fetal presentation, amniotic fluid volume (AFV), cardiac activity, placental position, fetal growth parameters, and number of fetuses. It is also used to perform an anatomic survey of the fetus (ACOG, 2009). Limited examinations are performed for specific indications such as identifying fetal presentation during labor or estimating AFV (ACOG, 2009). Specialized (also called detailed) or targeted examinations are performed if a woman is suspected of carrying an anatomically or physiologically abnormal fetus. Indications for this comprehensive examination include abnormal history or laboratory findings or the results of a previous standard or limited ultrasound examination. Specialized ultrasonography is performed by highly trained and experienced personnel (ACOG, 2009). Major indications for obstetric sonography are listed by trimester in Table 10-1. During the first trimester ultrasound examination is performed to obtain information regarding the number, size, and location of gestational sacs; the presence or absence of fetal cardiac and body movements; the presence or absence of uterine abnormalities (e.g., bicornuate uterus or fibroids) or adnexal masses (e.g., ovarian cysts or an ectopic pregnancy); and pregnancy dating. TABLE 10-1 MAJOR USES OF ULTRASONOGRAPHY DURING PREGNANCY Fetal heart activity can be demonstrated by about 6 weeks of gestation using transvaginal ultrasound. When the fetus is in a favorable position, good views of the fetal cardiac anatomy are possible in most patients at 13 weeks of gestation (Richards, 2012). Fetal death can be confirmed by lack of heart motion along with the presence of fetal scalp edema and maceration and overlap of the cranial bones. Gestational dating by ultrasonography is indicated for conditions such as uncertain dates for the last normal menstrual period, recent discontinuation of oral contraceptives, a bleeding episode during the first trimester, uterine size that does not agree with dates, and other high risk conditions. In fact, growing evidence suggests that pregnancies should be dated by an ultrasound performed before 22 weeks of gestation rather than by menstrual dates because the ultrasound dating is more accurate than even “sure” menstrual dates (Richards, 2012). A standard set of measurements has been accepted as being the most useful for determining gestational age. These measurements include the crown-rump length (after 10 weeks), the biparietal diameter (BPD) (after 12 weeks), the femur length (after 12 weeks), the head circumference, and the abdominal circumference (Fig. 10-3). An ultrasound examination performed for pregnancy dating between 14 and 22 weeks of gestation is comparable to one performed during the first trimester in terms of accuracy. However, after that time ultrasound dating is less reliable because of variability in fetal size (Richards, 2012).

Assessment of High Risk Pregnancy

Assessment of Risk Factors

Antepartum Testing

Biophysical Assessment

Daily Fetal Movement Count

Ultrasonography

Levels of Ultrasonography

Indications for Use

FIRST TRIMESTER

SECOND TRIMESTER

THIRD TRIMESTER

Fetal Heart Activity.

Gestational Age.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree