Can patency be maintained?

What strategies are required to protect the airway?

Presence of foreign body, risk of loose teeth, blood, etc.

Secretions – suction with care to remove.

Ability to respond; cough, gag and swallow reflexes. The reaction to suction can give good indication of these factors.

Check position of endotracheal tube if intubated. If not and required, arrange for intubation, support process and secure endotracheal tube.

Listen to lungs for any unusual sounds (wheeze, crepitations, rales, rhonchi, stridor. etc.).

Check ventilator settings to ensure they are optimal.

Assess perfusion – temperature of extremities, capillary refill time, presence of pulses and character of these, such as volume, rate. Attach saturations probe, note wave form.

Colour of child.

Listen to apex rate, rhythm and any unusual characteristics such as murmurs.

Linked to the stability of a child’s circulation is the assessment and management of pain and the need for sedation (see Chapter 13).

Second-Level Priorities

These can be linked to major body systems and include (in no order of priority as the homeostasis of systems are so interlinked):

- Fluids and drugs – renal.

- Nutrition – gastrointestinal.

- Potential impact on development and disability – neurological.

- Essential nursing care – potential to affect all body systems.

Fluids and Drugs

Management of fluids and electrolytes is important because most children in critical care units will require intravenous fluids (IVFs) and may have shifts of fluids between intracellular, extracellular and vascular compartments. For the calculation and management of a child’s fluids and therapy an approximate weight is required. The laminated and colour-coded Broselow tape is one means of determining the weight of the child.

Place the tape alongside the child who is lying in a supine position and extend the legs so the knees are not bent. Adjust the foot so the toes are pointing straight up. To measure ensure the red arrow is positioned and aligned with the top of the child’s head – red to head. Look at the subdivision of the coloured areas directly under the sole of the foot. Decide which of the subdivisions the child belongs in for weight classification. The Broselow tape works best for infants and when the child is within normal/average size for their age. If the child is obese, there is a potential risk of under-resuscitation (Nieman et al. 2006).

Alternatively, if the child’s age is known, one of the following formulae can be used to calculate a working weight in kg (Advanced Life Support Group 2011):

- 0–12 months − (0.5 × age in months) + 4

- 1–5 years − (2 × age in years) + 8

- 6–12 years − (3 × age in years) + 7

This can be used to calculate their maintenance fluids as shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 At-a-glance fluid calculator

| Weight of child (kg) | Fluid maintenance required ml/24 hour |

| <2 kg | Best calculated on individual basis depending on renal function and weight increases |

| 2–10 kg | 100 ml/kg |

| 10–20 kg | 1000 ml + 50 ml for each 1 kg above 10 kg |

| 20 kg to maximum | 1500 ml + 20 ml for each 1 kg above 20 kg Maximum daily amount: girls 2000 ml Maximum daily amount: boys 2500 ml |

| Adjustments and increases | Examples of need to increase: Hypovolaemia – may require a bolus of 10–20 ml/kg of 0.9% sodium chloride which may be repeated. This is in excess of their daily calculations. Severely dehydrated state where there are multiple physical signs present, cold pale peripheries with prolonged capillary return time, decreased skin tone, loss of ocular tension, when the infant has a fontanel this may be sunken +/− acidosis and hypotension. Anticipated massive fluid loss such as burns. Pyrexia. If unable to concentrate urine or where there has been excessive secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), e.g. pneumonia, head injury, meningitis. When having phototherapy or under a radiant heater. Examples of need to decrease: Waterlogged and oedematous children. When they are mechanically ventilated and are having heavily humidified gas. Renal impairment. Major head injury. |

Children admitted to critical care need to have their urea, electrolytes and serum glucose checked on admission and 3–4 hours after commencing IVs, with subsequent tests according to the results and their clinical situation until they are stable. Once stable the U&Es need to be checked at least daily.

Acceptable Fluids

In the newborn and during infancy 10% dextrose may be used with sodium and potassium additives as prescribed, titrated to individual requirement.

Other suitable maintenance fluids include 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.9% NaCl with 5% dextrose and 0.45% NaCl with 5% dextrose. Additional electrolytes are added as prescribed. Nurses need to be cautious as to the concentration of these, as strong solutions increase the risk of extravasation injury. Some electrolytes (e.g. calcium) need to be given centrally.

It is advisable that the administration of the maintenance fluids is not interrupted so a second cannula should be inserted for the administration of drugs. The fluid volume of medications and the administration of flushes between IV medications need to be recorded on the fluid balance chart.

Calorie Requirement and Nutrition

Children admitted to a critical care area are usually in a hypercatabolic state and will not recover unless their need for calories is addressed. A referral to the dietician should be made. Where it is not possible to commence an enteral feed owing to the condition of the child, consideration should be given to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (see Chapter 12).

Potential Impact on Development and Disability

The reasons for admission can have a profound impact of the future development of the child and even a positive outcome may include some level of disability. There are no guarantees for recovery in children who have been this sick and, even when recovering, a view towards cautious optimism is recommended until the outcome is certain. The neurological examination is one of the most difficult to perform in children who are sick, in pain and uncooperative, or are unconscious or sedated. The initial examination can only ever be a crude indicator until more sophisticated investigations can inform or confirm any concerns. The Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) scale is simple as it has only four possible outcomes for recording, unlike the assessment outcomes of the Pinderfield, Adelaide or modified Glasgow Coma Scale. The various coma scales continue to be adapted for use with immature children and to meet the challenges of assessing children who are heavily sedated (Tatman et al. 1997). Any scale is only as good as its users and there is evidence to support the assertion that the more complex the tool the less reliable it can be, thereby increasing the risk of inaccurate results (Barrett-Goode 2000). It is important that nurses are familiar with their use and regularly check their scores with colleagues to ensure inter-rater reliability.

Despite the difficulties of assessment and the high risk of morbidity and mortality it is important to attempt a thorough assessment as prompt, specialist neuro-critical care is associated with improved outcome (Moppett 2007) as there is less risk of secondary brain injury.

Indicators of Brain Injury

Thermal instability with hypothermia, a complication of a brain injury which disturbs hypothalamic activity and hyperpyrexia, may result from dysautonomias (a broad term which describes a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system).

Circulatory dysautonomia may result in tachycardia, syncope and hypotension caused by autonomic instability. (For assessment of a catastrophic neurological event and assessment of brain stem functioning see Chapter 7.)

An eye examination for reflexes and anomalies is a pivotal indicator of neurological function (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Eye examination

| Structure | Assessment |

| Ocular appearance and response | Open the eyes with care if there is no spontaneous eye opening or in response to request in cognisant children, and note the position of the pupils at rest. Document any spontaneous eye movements, any apparent nystagmus and any dysconjugate or conjugate eye position. When catastrophic brain injury is suspected the medical team may carry out an assessment of the oculocephalic reflex ‘doll’s eye’ where a rapid rotation of the child’s head right and left should result in movement of the pupils where the neural pathway is intact. In an abnormal response the pupils stay fixed in the position they were in when the manoeuvre was commenced and do not deviate. |

| Corneal reflex | The level of inhibited corneal reflex is proportional to the level of coma. |

| Pupil size and reaction | Pupil reaction and size are variable signs and can be indicative of a problem, but may not be a conclusive finding. The pupils in health and under normal circumstances should react and constrict when exposed to light. Asymmetrical pupils need further investigation. A fixed dilated pupil needs urgent attention. Pinpoint pupils may be a feature of opiate sedation and analgesia. |

| Fundus | This can be distressing for the child so is best left until last; the child can then rest and recover from the examination. Infants and small children may need mydriatrics to facilitate a good view. Papilloedema is an accurate indicator of raised intracranial pressure. It usually takes time to build up so in cases where there could be raised intracranial pressure this investigation ought to be checked again as the child’s condition dictates. Papillitis may be a feature of encephalitis. The presence of retinal haemorrhages might also indicate bleeding elsewhere. |

Once the child is stable with a secure airway, adequately ventilated, pink, warm and well perfused with fluid management planned it is time to take a small step back and review in order to plan ongoing management, formulate a plan of care and take a more thorough history. This will help to inform essential nursing care.

Essential Nursing Care

Skin Assessment

The sicker the child the more their skin integrity is at risk for a number of reasons: poorly perfused tissues leading to hypoxia, poor availability of nutrients and prolonged periods of immobility. Urinary and faecal incontinence can damage the skin; the use of pads can create a moist, warm micro-environment that can macerate the perianal and sacral areas (for more consideration of skin at risk, see Chapter 14). Intubation and airway/respiratory management and indwelling lines can restrict the positions of rest for nursing these children. It is important to assess and document the state of the child’s skin using a validated and reliable assessment tool (Willcock et al. 2008). Using the tool to inform an individualised plan of care in which the parents can participate can reduce the risk of developing sores, which is vitally important as the impact of skin breakdown has a considerable cost both economically and in the child’s suffering. The true incidence of this complication in this population is unknown (Schindler et al. 2007). However, the condition is preventable with scrupulous attention to the areas at risk and by anticipating iatrogenic risks such as name-bands being applied too tightly or a poorly fixed endotracheal tube.

Bowel and Bladder Care in the PICU

Children are at risk of constipation in the PICU as a result of reduced mobility, reduced enteral intake, dehydration through fever or their pathology, and opiate analgesics. Even for children who have attained conscious control over their bowel movement, the altered level of consciousness because of illness or sedation, not to mention their circumstances, may make it impossible to communicate their need to evacuate their bowels. Owing to the function of the bowel wall in absorbing water, any retained faeces will get harder and be more difficult to pass. This may manifest itself by the child seeming to be less settled or more irritable. The ability to override the defecation reflex can only be maintained for a short period and the child will eventually defecate. The nurse needs to ensure the continence pad is the appropriate size, not creased and the child’s skin is cared for following reflex evacuation and their dignity maintained.

Initially, the level of bowel care is conservative and the child will be allowed 24–48 hours before intervention. The Bristol stool chart (Lewis and Heaton 1997) can be used to support the nurse in making an assessment of the need for intervention as it demonstrates a range of stool characteristics. The characteristic of the child’s stools will dictate the further need for intervention in the form of stool softening agents, small enema or suppository.

Diarrhoea can be problematic in the PICU from both a practical management perspective and its challenge to accurate fluid measurement. For the infant and young child nappies and pads can be used. These need to be changed frequently and weighed as part of a fluid management strategy. For the adolescent or young person a range of temporary containment devices can be used. These are ideal for bed-bound and incontinent patients who have liquid or semi-liquid stools. They are designed to safely and effectively contain and divert faeces and help prevent complications such as wound contamination and skin breakdown (Ousey et al. 2010).

Because of the need to monitor fluid balance the majority of children in PICU will have an indwelling urinary catheter. Short-term use of an indwelling urethral catheter is a safe and effective means to ensure bladder health and assess renal function; however catheterisation of the bladder is thought to be the most common risk factor for acquired urinary tract infection (Bray and Sanders 2006). Meatal cleansing is an integral part of good catheter care. Evidence indicates that normal genital hygiene is sufficient to achieve good meatal hygiene and that a strict regimen using antiseptics can be detrimental as it can compromise the normal skin flora (Leaver 2007).

To minimise the risk of ascending infection the breaking of the closed system should be kept to a minimum, the nurse should wear gloves and, before emptying the collecting bag, the tap should be cleaned with 70% isopropyl alcohol.

Oral Hygiene

This is an essential nursing procedure and should be considered an integral part in maintaining the general hygiene of the patient; it is performed to maintain oral health (Whiteing and Hunter 2008). Oral health is more than just cleaning teeth or preventing dental caries; it involves consideration of the lips, teeth, gums, tongue, palate and surrounding soft tissues. There needs to be a comprehensive assessment of the mouth and a plan of care formulated (Huskinson and Lloyd 2009). When teeth and gums are not brushed regularly, dental plaque, a biofilm of organisms comprising approximately 70% microorganisms and 30% inter-bacterial substances, accumulates (Huskinson and Lloyd 2009). Plaque left undisturbed produces acid which can lead to demineralisation of the tooth surface. Plaque can harden and result in the formation of calculus which is difficult to remove. In essence poor oral hygiene provides a source of bacterial infection (Huskinson and Lloyd 2009) and can be associated with ventilator-associated infection (Koeman et al. 2006), although the decision to use of chlorhexidine mouthwash in young children needs to be assessed on an individual basis. Use of an assessment tool can identify the children most at risk and children’s intensive care nurses can be creative when aiming to encourage salivation to keep the mouth moist; for example, when dealing with a nasally intubated child or a child on nasal CPAP a pacifier can be offered (McDougall 2011) which also helps keep a good seal. Some children are more at risk from poor or incomplete oral hygiene than others (for additional consideration of oncology children, see Chapter 11).

Eye Care

Infants and children who are heavily sedated can lose their blink reflex which can put the eye at considerable risk when turning and handling. When this is combined with impairment of the normally closing eyelid it can lead to the drying of the surface membrane and corneal tissue (Douglas and Berry 2011).

There is considerable variation in the way eye care is performed and what can be used to maintain eye health. The use of a lubricant with a hydrogel dressing to promote eyelid closure is highly endorsed in much of the literature (Sorce et al. 2009). Douglas and Berry (2011) have developed an eye assessment tool and a care pathway recommending levels of intervention depending on the condition of the child’s eyes and the level of assessed risk.

Passive Limb Physiotherapy

The sedated infant or child is at risk of limb stiffness, muscle wastage, foot drop and (occasionally) contractures. The longer the period of sedation the more the child is at risk. There is considerable variation in practice with regard to positioning and passive limb movement (Wiles and Stiller 2009) and there are cost implications in using a highly skilled physiotherapist to perform these activities (Stiller 2000). Safety issues will need to be considered when mobilising and moving the critically ill child (Stiller 2007), however these risks need to be set against the risk of providing care which is detrimental to the child’s future functioning.

Children’s nurses, with the help and support of the parents, are ideally placed to maintain or improve the child’s range of motion, soft tissue length, muscle strength and function by careful positioning, the use of splints and supports as appropriate, and when moving the child or performing other planned interventions by putting the child’s limbs through repeated sequences of natural movements. In addition, enhancing the circulatory return will decrease the risk of thromboembolism.

Resuscitation in the PICU

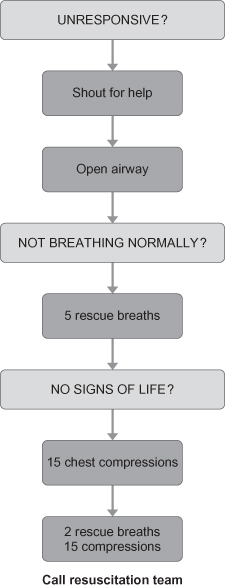

The outcome from cardiopulmonary arrests in children remains poor and identification of the preceding stages of respiratory failure or cardiac compromise is a priority as early intervention may be life-saving (UKRC 2010). In children, cardiopulmonary arrest is usually secondary and caused by respiratory or circulatory failure. Secondary arrest is much more frequent (and preventable) than primary arrest caused by arrhythmias. The platform of resuscitation for children who are in the PICU remains the basic life support (Figure 2.1): ABC with airway management and manoeuvres, the delivery of rescue breaths and compressions performed to the ratio of 15:2 as recommended by the UKRC (2010).

Figure 2.1 Paediatric basic life support (healthcare professionals with a duty to respond).

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree