This case study demonstrates the enormous difficulty staff can face when breaking bad news. It highlights the importance of education and training to develop the knowledge and skills needed to fulfil this role.

Bereavement

To support parents nurses need to gain an understanding of grief and the bereavement process. Nurses are the one group of healthcare professionals who are likely to care for the child and family during the period prior to and immediately after death (Greenstreet 2004). Hindmarch (2009) defines bereavement as what happens at the time of death, grief is the reaction to that death, and mourning is how we express our loss. Loss is a recurring experience from birth to death and can be experienced in a number of ways:

- Illness.

- Diagnosis.

- Prognosis.

- Bereavement.

- Disability.

- Family breakdown.

- Unemployment.

Each individual will develop their own coping strategies in order to deal with loss. Child bereavement is the greatest loss that a parent can experience. It should be remembered that loss is a normal experience and that people demonstrate resilience. How that resilience is expressed in the bereaved will depend on cultural, social and spiritual experiences (Field and Payne 2003). The response to loss may be significantly different from that which the nurse expects. A failure to show emotion does not mean that the parent is not distressed; it may be that the individual is so overwhelmed by what they are experiencing that they cannot make a response. Culturally, the British both hide and deny their emotions and tend not to be expressive, with the goal of maintaining ‘a stiff upper lip’ (Read 2002). Often this is a façade that cannot be maintained and when the cracks appear emotions will be expressed.

This is an unusual but not a unique response and it is possible that the mother experienced more distress by staff repeatedly encouraging her to enter the unit. Although the staff believed they were acting in the best interests of the baby and mother, to some degree they were responding to what was perceived as an abnormal response to loss and impending bereavement. Parents will often withdraw from the PICU environment so that they do not have to face the death of their child. Avoidance could be supported, but it is important to be honest with the parents and continue to reinforce the facts around the deterioration and subsequent loss of the child.

It is an expectation that children will outlive their parents but this is not true for all children and the loss of a child will have a profound effect on the length and intensity of the grief experienced. Worden (1991) identifies a number of phases to the grieving process. First, the individual will accept the reality of loss, they will experience pain and grief, they will need to adjust to a new environment and emotionally relocate the deceased person, allowing them to move on. It is questionable how many parents will manage to move on. There will be a period of adjustment, but some parents will experience pathological grief which will be long-lasting. Grief is not a static process but evolves over time. A number of grief theories have been developed and are summarised in Table 17.1.

Table 17.1 Grief theories

| Kübler-Ross (1969) | Bowlby (1980) | Worden (1991) |

| Denial | Numbness | Accepting the reality of loss |

| Anger | Yearning and searching | Working through the pain and grief |

| Bargaining | Disorganisation and despair | Adjusting to life without the deceased |

| Depression Acceptance | Reorganisation of behaviour and adjustment | Emotionally relocating the deceased and moving on |

Theories of Grief

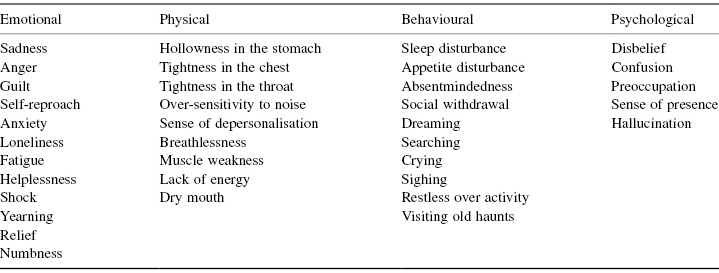

It is important to have some knowledge of these theories, however it must be appreciated that individuals will progress through the stages at their own pace. Anger may be the prevailing emotion for some time. Parents will grieve at different times. One parent may make an adjustment to life without their child, while another may continue to work through the pain and grief without coming to a period of resolution. Stroebe and Schut (1999) have developed a dual-process model of coping with bereavement in which the individual will engage in a range of loss-oriented and restoration-oriented behaviour. This can be applied to families when they are given a prognosis for their child or following the death of a child. In loss-oriented activities the individual focuses on the loss and grief, whereas restoration-oriented activities are based on moving forward. The individual is distracted from grief, doing new things and developing new roles and identities. Thomas and Chalmers (2009) note that this behaviour can be gender-specific. Women may need more help to engage in restoration activities,whereas men may need help to face their grief and loss and express it so that emotions can be explored. Worden (1991) identifies a range of grief responses (Table 17.2).

Table 17.2 Grief responses

Source: adapted from Worden 1991.

The grieving process can commence at diagnosis, prognosis or following the death of the child. It is important for nursing staff to look for these responses in the families that they are caring for and facilitate the appropriate support.

Caring for the Child after Death

Once a child has died in PICU it is incumbent on the staff to continue to provide appropriate care. It is important to establish any religious or cultural rituals which should be adhered to before handling the body. Once it has been established that the body may be handled by staff, the body may be washed. It is important to offer parents the chance to assist in this care. Any drains or tubes can be removed at this point unless there is a possibility of a coroner’s postmortem. The removal of indwelling equipment can be proceeded with once the coroner’s officer agrees to it. If any lines or drains have to be kept insitu they can be covered by gauze or other appropriate dressings. If the child is older, parents will usually have numerous mementos and photographs at home. However, it is still important to ask if they would like a lock of hair or hand- and footprints taken for babies and small children. For neonates parents may wish to have photographs taken. Photographs in which the baby is dressed will be better received than photographs of them taken naked. Clothing will also cover marks left from lines and surgical incisions. Most units will have access to a digital camera, alternatively hospital photographers can take the photograph. If staff have to use an instant camera it is important to make a family member aware that these pictures can fade over time so should be digitised to preserve the image. Mementos such as photographs can provide lasting comfort to bereaved parents (Osborne 2000).

Families should be given the time and space in which to grieve with their child. Kübler-Ross (1983) identified that the long-term outcomes of bereavement are improved if those who are bereaved can see and spend time with their loved one’s body. PICUs are set up for acute, intense care. Where possible a side-room or quiet room should be made available for the family to spend time with their child. It is important that nurses negotiate with the family whether they want a nurse to stay with them or to come in periodically. Davies (2005), following interviews with bereaved mothers, found that they need time, space and privacy to be with their dying child and with the child’s body after death.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree