Chapter 41 Physiology, assessment and care

At the end of this chapter, you will have:

Introduction

The baby as an individual

The baby is recognized as a person (Children Act 1989) with individual needs that require the midwife to act as an advocate and act with duty of care for those needs. Rather than relying on verbal responses, the midwife communicates with the baby via sight, touch and hearing. This must be a focused activity in order to absorb all of the information provided by the baby’s responses and behaviour. Upon completion of the examination, the findings must be discussed with the parents so that the baby’s management and care can be planned as a partnership. Prior to the examination, the midwife must gain consent from the legal guardian. If an unmarried woman is unable to give consent, then it has to be gained from the woman’s next of kin. This should be discussed with the woman when she first attends for care, so that she can provide this information, which may be required in an emergency.

If the woman wishes the baby to be given oral (or no) vitamin K preparation, the midwife has a duty, under statute (NMC 2004), to ask the paediatrician to see the mother and ensure that the decision-making outcome is recorded in the baby’s notes. If invasive treatment is required, then consent needs to be obtained by the person implementing the invasive procedure, so that the parents can be given the information they need. If the parents feel that they have not been given adequate information, then consent may not be deemed valid (DH 2001).

Applied physiology

Respiratory system

Lung fluid

Lung fluid, a silky clear fluid which may be seen draining from the baby’s mouth at delivery, is different to surfactant. Its function appears to be mainly for cell proliferation and differentiation. At birth, the lungs must switch function from the secretion of fluid to absorption of gases. The catecholamine surge which occurs during labour is probably the final catalyst to complete this change (Milner & Vyas 1982). Some lung fluid is swallowed and then excreted via the fetal kidneys and into the amniotic fluid. At term, 10–25 mL/kg body weight of liquid remains, which is either expelled via the upper airways or absorbed via the lymphatic system of the lungs, a process commenced at the onset of labour and completed at birth (Taeusch et al 2004).

If delivered by elective lower section caesarean section (ELSCS), the burst of catecholamines provided by the onset of labour will not occur. The lungs will not have been compressed to expel lung fluid. The lung fluid is not absorbed and may be present following birth. Therefore, the midwife will need to observe the baby closely for signs and symptoms of transient tachypnoea of the newborn (TTN) (see Ch. 45).

Fetal breathing movements

Fetal breathing movements occur from 11 weeks of gestation. As the fetus grows, the strength and frequency of breathing movements increases until they are present between 40–80% of the time at a rate of 30–70 breaths per minute (Davis & Bureau 1987).

Respiration in the neonate

Ribcage and respiratory musculature are immature and will continue to develop into adulthood (Harris 1988). The diaphragm and abdominal muscles are used for respiratory movement and it may be difficult to see movement of the chest when counting respiratory rate (more easily measured by observing the rise and fall of the baby’s abdomen).

Tachypnoea (rate of >60) is a result of increased carbon dioxide and baroreceptors providing the information to the medulla; thus, an increased respiratory rate may reduce the respiratory acidosis (see Ch. 45).

Abnormal signs

Cardiovascular system (CVS) in the embryo and fetus

Changes at birth

Following the birth and the taking of the first breath the right atrial pressure is lowered and the left atrial pressure is increased slightly, causing closure of the foramen ovale. Aeration of the lungs opens up the pulmonary capillary bed, lowering vascular resistance and increasing the pulmonary bed blood flow. The neonate can generate a pressure of up to 70 cmH2O during inspiration and 20–30 cmH2O on expiration (Strang 1977). This is thought to force fluid out of the lungs to overcome the high resistance and surface tension of the alveoli and to be necessary to establish lung volumes distributing gas through the lungs.

Changes in the blood

After birth, the high number of red blood cells is not required, so haemolysis of excess red blood cells takes place. This may result in physiological jaundice of the newborn within 2–3 days of birth (see Ch. 46). The conversion from fetal to adult haemoglobin (HbA) starts in utero and is completed during the first year or two of life. By the age of 3 months, the haemoglobin has fallen to about 12 g/dL.

Temperature control

Following birth, the baby must adjust to a lower and labile environmental temperature. The heat-regulating mechanism in the newborn is inefficient and the body temperature may drop unless great care is taken to avoid chilling. Heat is lost by radiation, convection, evaporation and conduction. These factors can be rectified if the baby is born into a warm environment of 26°C, dried carefully and wrapped warmly or provided with skin-to-skin contact with the mother (see Ch. 42).

Skin

The skin of full-term newborns is covered with a varying amount of vernix caseosa, a thick white, creamy substance. This forms between 17 and 20 weeks’ gestation and by 40 weeks is found primarily in creases such as the axilla, neck and groins, acting as protection during uterine life (Moore & Persaud 2007). Vernix is a perfectly balanced moisturizer and any surplus should be massaged gently into the baby’s skin after the birth.

Gastrointestinal system (see website)

The midwife needs to understand glucose metabolism of the fetus and newborn in order to support the woman in her chosen method of infant feeding (de Rooy & Hawdon 2002) (see Ch. 43).

Glucose metabolism

See website for fetal metabolism.

Metabolic adjustments after birth

After birth, normoglycaemia must be maintained to protect brain function and to adapt to the intermittent delivery of milk into the gut for nutritional needs. The normal term neonate is able to adapt physiologically to episodes of starvation by utilizing ketone bodies. This is reflected in a postnatal fall in blood glucose concentration, which may be wrongly viewed as pathological and managed accordingly (de Rooy & Hawdon 2002). Following birth, the breakdown of glucose continues under the influence of insulin, but about 8 hours after birth, the baby begins to switch to glucagon metabolism.

Central nervous system

At birth, the baby’s autonomic system maintains homeostasis of all major organs, regulating temperature and cardiorespiratory function. The well newborn will have mature autonomic and motor systems which can be assessed by the ability to maintain stable cardiorespiratory function. If the baby is unwell or premature, handling will stress the autonomic system and the baby can become cyanosed and bradycardic (Roberton & Rennie 2001).

State of consciousness in the newborn is influenced by the reaction to stimuli, and understanding the baby’s level of consciousness ensures sensitive care and management in assisting in the adaptation to the environment and advance through stages of consciousness. Providing this information to the mother assists her in caring for her baby, may assist feeding, and utilizes the baby’s energy and available resources effectively (see Box 41.1).

Box 41.1

States of consciousness in the newborn (Brazelton & Nugent 1995)

Awake states

Protection against infection

In utero, the fetus is protected from infection by the intact amniotic sac and the barrier mechanism of the placenta, although certain microorganisms do cross the placenta and may infect the fetus (see Ch. 47). During the last trimester of pregnancy, there is a transplacental transfer of IgG from the mother to the fetus, providing protection against the infectious diseases to which the mother has antibodies. These antibodies provide baby passive immunity for about 6 months (Remington & Klein 2000).

Care at birth

Preparation

Preparations should be made prior to the baby’s birth and these include identifying women whose babies are at increased risk or who will require specialist care following delivery. The midwife must be prepared to provide care for ‘high-risk’ and ‘low-risk’ women (see Box 41.2), though research indicates that the classification of risk factors remains a debatable area.

Box 41.2

Risk factors for specialist care (Levene & Tudehope 1993)

The development of complications during labour and birth is a major contributor to increased neonatal mortality and morbidity (MCHRC 2001). The midwife can identify that all is normal, detect any deviations and make appropriate referral or alter management of care accordingly.

The Apgar score

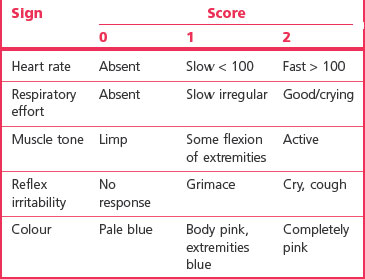

The Apgar score, devised by Virginia Apgar in 1953 (Levene & Tudehope 1993), is a universally and commonly used quantitative measure of the neonate’s wellbeing at and around birth, though criticized for its simplicity. Five indicators are used to measure this: heart rate, respiratory effort, colour, muscle tone and response to stimuli (Table 41.1).

It is also advisable, if more than one practitioner is present at a delivery where resuscitation is undertaken, that the baby’s Apgar score is agreed between practitioners prior to the formal record being made. Disagreements can be discussed with the supervisor of midwives and senior neonatologist. It is important for the future management of the newborn’s wellbeing that an accurate assessment is given (UK Resuscitation Council 2006).

Maternal–infant relationship

Research illustrates mothers’ reactions to newborn infants. The mother’s first response is to touch her baby (easier if the baby is naked) with fingertips, progressing to a protective caressing movement. The mother will often then move the baby to a position to facilitate face-to-face eye contact. Throughout this time, she talks to the baby in a higher-pitched voice than usual (Klaus & Kennell 1976). Early research suggested the existence of a ‘sensitive time’ around the birth, at which the mother and baby should be encouraged to be together, and that women missing this time were at risk of neglecting or abusing their infants. However, Brazelton postulated that even should parent and child have to be separated, if the attendants ensure that the mother has photographs of her baby and is involved in the baby’s management and care, cuddling or even just touching her child, the relationship can be effectively preserved and nurtured (Brazelton 1983).

Warmth

The baby, accustomed to a constant intrauterine temperature of 37.8°C, is born into a much cooler atmosphere, ideally 26°C. At birth, the baby should be dried immediately to prevent evaporation and handed to the mother to keep warm, avoiding unnecessary exposure. Warm covers are placed over the baby, if necessary for skin-to-skin contact, and later the baby should be dressed, covered appropriately and placed in a preheated cot. Within an hour of birth, the baby’s axillary temperature is taken using a low-reading thermometer (see Ch. 42).

Vitamin K

It has been advised that all babies should be given vitamin K (DH) and parents should be provided with information on whether or not to give vitamin K and the route of administration as advised in the Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin (www.dtb.org.uk/dtb/index.html).

Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) (formerly known as haemorrhagic disease of the newborn) is a bleeding tendency which results from a lack of ability in the newborn to utilize vitamin K (see Ch. 44).

Signs and symptoms include bleeding from:

Examination of the newborn

Three types of examination of the newborn are carried out:

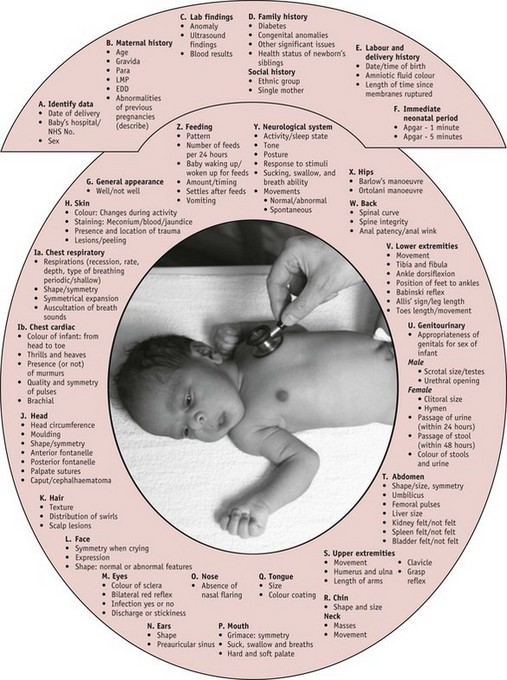

Each examination has a slightly different purpose, but all should follow a systematic process, and be undertaken with the principles set over the following pages, which will provide the midwife with the best means of assessment (see Fig. 41.1).

Initial post-birth examination

Prior to this first examination, the baby should have at least 1 hour following birth to recover (NICE 2006). This allows mother and baby time to adapt to physiological changes and gives the baby time to adapt to the environment and, if breastfeeding, to feed successfully.

The holistic examination

Since 1994, increasingly midwives have undertaken this holistic examination rather than their medical colleagues, providing continuity of care as recommended by Changing childbirth (DH 1993), facilitating the midwife’s self-audit and with the potential for improving interprofessional partnerships (Hall 1999).

The United Kingdom National Screening Committee (UKNSC) of the Newborn and Infant Physical Examination (NIPE) (UKNSC 2008) advocates the first holistic examination is undertaken within 72 hours of birth, allowing the postnatal transition of major organs, such as the heart, to take place prior to examination. This is done prior to discharge and transfer to the care of a health visitor and GP. It is expected that the midwife (NICE 2006) will care for the newborn from birth to 6 to 8 weeks. It is intended that the second holistic examination is combined into a single postnatal visit at 6 weeks to validate the woman’s wellbeing. In between those two examinations, the midwife will assess each baby, reviewing past and present individual history prior to deciding which criteria need assessment during physical examination and which can be validated through observation alone.

Examination of the newborn assessment tool

A clinical assessment tool (see website also) has been designed to assess the physiological and behavioural cues to assist the midwife to validate normality and recognize deviations (Michaelides 2010).

The tool consists of 26 criteria (Fig. 41.1 A–Z), the number of which that will be fully examined at each examination being dependent on the purpose of the examination, and the experience and training of the midwife.

Preparation

Preparation is vital to ensure a smooth and effective examination process. An area, to provide privacy and a controlled environment, needs to be set aside; an examining table with an overhead heater and light source can be utilized to examine babies at a height that will prevent practitioner back strain. It provides a safe environment for the baby (see Fig. 41.2) and a safe storage space for the required equipment (see Box 41.3). In the home environment, the midwife can use a changing mattress or table (or similar surface area) covered with a warm sheet/towel to examine the baby.

Physical assessment of the newborn

Formal assessment of the newborn

Physical examination of the newborn baby should be performed systematically, examining each physiological system to ensure entirety (see Fig. 41.1), using the skills of observation, palpation and, where relevant, auscultation. Each system should be critically evaluated, normality validated and deviations recognized. Where deviations occur, the midwife needs to ascertain the severity in order to plan appropriate management and transfer to the care of the neonatologist as appropriate.

History

Sexually transmitted diseases, if not treated in the antenatal period, may affect the baby postnatally and thus the baby will need to be observed for signs of infection (see Ch. 47).

When undertaken correctly, fetal surveillance (see Ch. 36) can assist the midwife to have the relevant practitioners present at birth. The type of birth may affect the management of the baby – after a protracted labour, the baby may be traumatized and may require an initial superficial examination to validate wellbeing, followed by a full examination when signs of recovery are apparent. Minimal handling may assist the shocked newborn to recover. The examination should last no longer than 15 minutes.

General appearance

A baby who has had a difficult birth may be very irritable or be in a deep sleep (State 1 – see Box 41.1), and the midwife uses the baby’s behaviour to guide the examination. The physical examination can be delayed until the baby is able to tolerate handling and an interim observational examination undertaken.