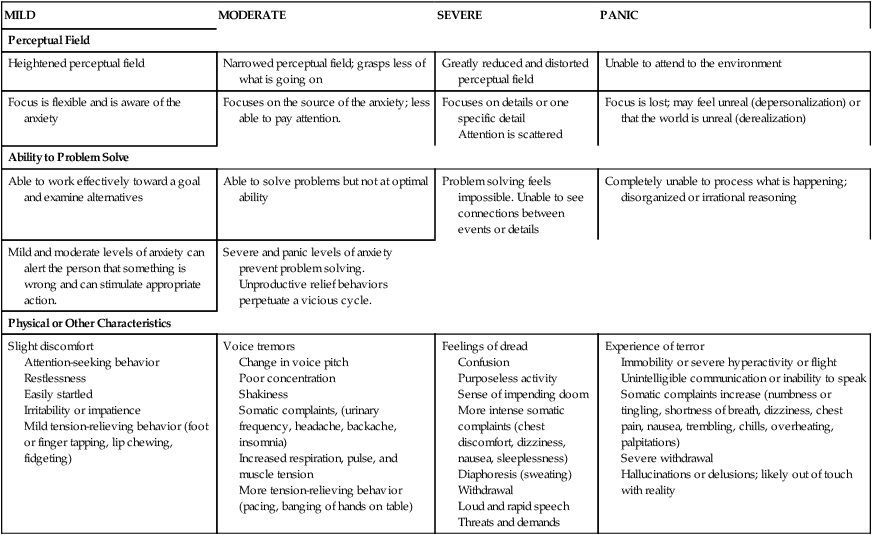

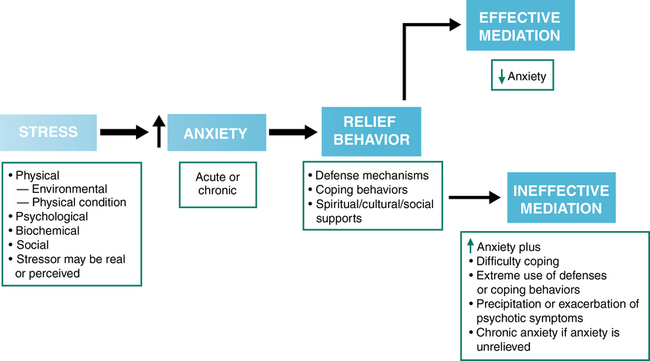

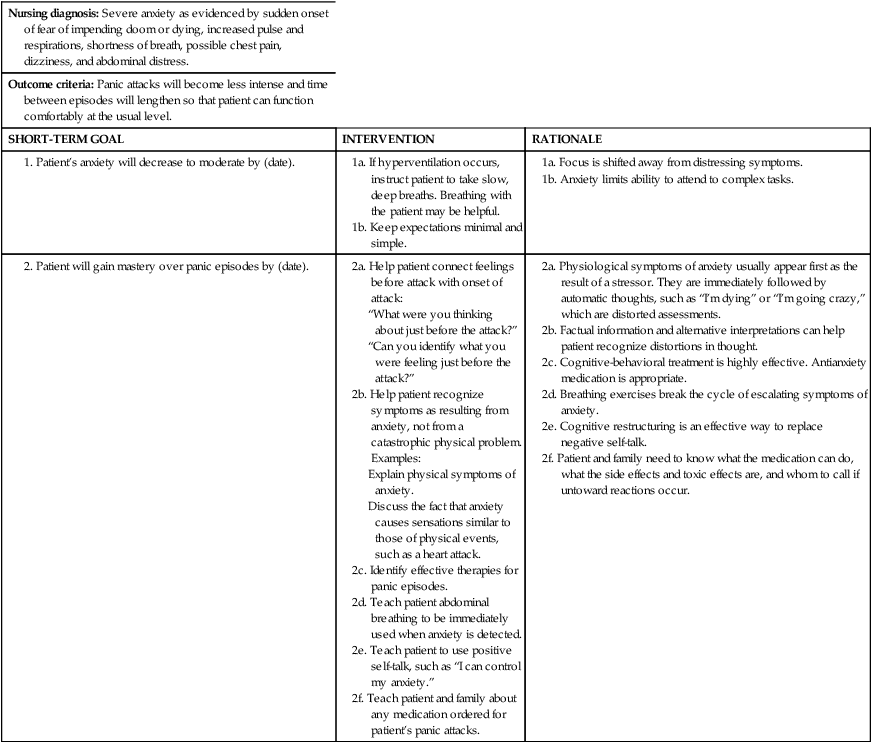

CHAPTER 15 Margaret Jordan Halter and Elizabeth M. Varcarolis 1. Compare and contrast the four levels of anxiety in relation to perceptual field, ability to problem solve, and physical and other defining characteristics. 2. Identify defense mechanisms and consider one adaptive and one maladaptive (if any) use of each. 3. Describe clinical manifestations of each anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder. 4. Identify genetic, biological, psychological, and cultural factors that may contribute to anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. 5. Describe feelings that may be experienced by nurses caring for patients with anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. 6. Formulate four appropriate nursing diagnoses that can be used in treating a person with anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. 7. Propose realistic outcome criteria for a patient with (a) generalized anxiety disorder, (b) panic disorder, and (c) obsessive-compulsive disorder. 8. Describe five basic nursing interventions used for patients with anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. 9. Discuss four classes of medications appropriate for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. 10. Describe advanced-practice and basic-level interventions for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis As discussed in Chapter 2, Hildegard Peplau had a profound role in shaping the specialty of psychiatric mental health nursing. She identified anxiety as one of the most important concepts and developed an anxiety model that consists of four levels: mild, moderate, severe, and panic (Peplau, 1968). The boundaries between these levels are not distinct, and the behaviors and characteristics of individuals experiencing anxiety can and often do overlap. Identification of the specific level of anxiety is essential because interventions are based on the degree of the patient’s anxiety. As anxiety increases, the perceptual field narrows, and some details are excluded from observation. The person experiencing moderate anxiety sees, hears, and grasps less information and may demonstrate selective inattention, in which only certain things in the environment are seen or heard unless they are pointed out. The ability to think clearly is hampered, but learning and problem solving can still take place although not at an optimal level. Sympathetic nervous system symptoms begin to kick in. The individual may experience tension, pounding heart, increased pulse and respiratory rate, perspiration, and mild somatic symptoms (e.g., gastric discomfort, headache, urinary urgency). Voice tremors and shaking may be noticed. Mild or moderate anxiety levels can be constructive because anxiety may be a signal that something in the person’s life needs attention or is dangerous (see the Case Study and Nursing Care Plan for moderate anxiety on the Evolve website). The perceptual field of a person experiencing severe anxiety is greatly reduced. A person with severe anxiety may focus on one particular detail or many scattered details and have difficulty noticing what is going on in the environment, even when another points it out. Learning and problem solving are not possible at this level, and the person may be dazed and confused. Behavior is automatic and aimed at reducing or relieving anxiety. Somatic symptoms (e.g., headache, nausea, dizziness, insomnia) often increase; trembling and a pounding heart are common, and the person may experience hyperventilation and a sense of impending doom or dread (see Case Study and Nursing Care Plan 15-1). Adaptive use of defense mechanisms helps people lower anxiety to achieve goals in acceptable ways. Maladaptive use of defense mechanisms occurs when one or several are used in excess, particularly in the overuse of immature defenses. Figure 15-1 operationally defines anxiety and shows how defenses come into play. With the exception of sublimation and altruism, which are always healthy coping mechanisms, most defense mechanisms can be used in both healthy and unhealthy ways. Most people use a variety of defense mechanisms but not always at the same level. Keep in mind that evaluating whether the use of defense mechanisms is adaptive or maladaptive is determined for the most part by their frequency, intensity, and duration of use. Table 15-2 describes defense mechanisms and their adaptive and maladaptive uses. TABLE 15-2 ADAPTIVE AND MALADAPTIVE USES OF DEFENSE MECHANISMS Individuals with anxiety disorders use rigid, repetitive, and ineffective behaviors to try to control their anxiety. The common element of such disorders is that those affected experience a degree of anxiety so high that it interferes with personal, occupational, or social functioning. The presence of chronic anxiety disorders may increase the rate of cardiovascular system-related deaths. Anxiety disorders tend to be persistent and often disabling. Chapter 10 offers a more complete description of the debilitating effects of chronic stress and resultant anxiety. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), the term anxiety disorder refers to a number of disorders, including: Separation anxiety is a normal part of infant development; it begins around 8 months of age, peaks around 18 months, and begins to decline after that. People with separation anxiety disorder exhibit developmentally inappropriate levels of concern over being away from a significant other (Bostic & Prince, 2010). There may also be fear that something horrible will happen to the other person and that it will result in permanent separation. The anxiety is so intense that it distracts sufferers from their normal activities, causes sleep disruptions and nightmares without the significant other close by, and is often manifested in physical symptoms such as gastrointestinal disturbances and headaches. This problem is typically diagnosed prior to the age of 18 after about a month of symptoms. Separation anxiety may develop after a significant stress, such as the death of a relative or pet, an illness, a move or change in schools, or a physical or sexual assault (Ursano et al., 2011). Recently, clinicians have begun to recognize an adult form of separation anxiety disorder that may begin either in childhood or in adulthood. Those who are the subject of the attachment—a parent, a spouse, a child, or a friend—may grow weary of the constant neediness and clinginess. In fact, adults with this disorder often have extreme difficulties in romantic relationships and are more likely to be unmarried (Nichols, 2009). Characteristics of adult separation anxiety disorder include harm avoidance, worry, shyness, uncertainty, fatigability, and a lack of self-direction (Mertol & Alkin, 2012). It is accompanied by a significant level of discomfort and disability that impairs social and occupational functioning and does not respond well to the most popular type of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy. People who experience these attacks begin to “fear the fear” and become so preoccupied about future episodes of panic that they avoid what could be pleasurable and adaptive activities, experiences, and obligations. Table 15-3 outlines a generic nursing care plan for panic disorder, and the Evidence-Based Practice box provides additional information. TABLE 15-3 GENERIC CARE PLAN FOR PANIC DISORDER Consider the case of Daniel, who developed a profound fear of elevators after being trapped in one for 3 hours during a power outage. As his fear and anxiety intensified, it became necessary for him to use only stairs or escalators. He obsesses about the possibility that he will be forced to use an elevator in social situations and avoids attending events where this may occur. It has reached a point where even going inside closets or small storage rooms is unbearable. This fear of enclosed spaces is called claustrophobia. Other common phobias are listed in Table 15-4. TABLE 15-4 CLINICAL NAMES FOR COMMON PHOBIAS The key pathological feature of generalized anxiety disorder is excessive worry (Newman & Llera, 2011). Children, teens, and adults may experience this worry, which is out of proportion to the true impact of events or situations. Persons with generalized anxiety disorder anticipate disaster and are restless, irritable, and experience muscle tension. Decision making is difficult due to poor concentration and dread of making a mistake. Sleep disturbance is common because the individual worries about the day’s events and real or imagined mistakes, reviews past problems, and anticipates future difficulties. Fatigue is a noticeable side effect of this sleep deprivation. Refer to Table 15-5 for a generic care plan for generalized anxiety disorder. TABLE 15-5 GENERIC CARE PLAN FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER 1a. Conveys acceptance and ability to give help. 1b. Conveys calm and promotes security. 1d. Counters feeling of loss of control that accompanies severe anxiety. 1e. Reduces indecision. Conveys belief that patient can respond in a healthy manner. 1f. Reduces need to focus on diverse stimuli. Promotes ability to concentrate. 1g. Reduces anxiety and allows patient to use coping skills. 1h. Anxiety is transmissible. Displays of negative emotion can cause patient anxiety.

Anxiety and obsessive-compulsive related disorders

Anxiety

Levels of anxiety

Moderate anxiety

Severe anxiety

Defenses against anxiety

DEFENSE MECHANISM

ADAPTIVE USE

MALADAPTIVE USE

Compensation is used to counterbalance perceived deficiencies by emphasizing strengths.

A shorter-than-average man becomes assertively verbal and excels in business.

An individual drinks alcohol when self-esteem is low to temporarily diffuse discomfort.

Conversion is the unconscious transformation of anxiety into a physical symptom with no organic cause.

No example. Almost always a pathological defense

A man becomes blind after seeing his wife flirt with other men.

Denial involves escaping unpleasant, anxiety-causing thoughts, feelings, wishes, or needs by ignoring their existence.

A man reacts to the death of a loved one by saying “No, I don’t believe you” to initially protect himself from the overwhelming news.

A woman whose husband died 3 years earlier still keeps his clothes in the closet and talks about him in the present tense.

Displacement is the transference of emotions associated with a particular person, object, or situation to another nonthreatening person, object, or situation.

A child yells at his teddy bear after being picked on by the school bully.

A child who is unable to acknowledge fear of his father becomes fearful of animals.

Dissociation is a disruption in consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment that results in compartmentalizing uncomfortable or unpleasant aspects of oneself.

An art student is able to mentally separate herself from the noisy environment as she becomes absorbed in her work.

As the result of an abusive childhood and the need to separate from its realities, a woman finds herself perpetually disconnected from reality.

Identification is attributing to oneself the characteristics of another person or group. This may be done consciously or unconsciously.

An 8-year-old girl dresses up like her teacher and puts together a pretend classroom for her friends.

A young boy thinks a neighborhood pimp with money and drugs is someone to look up to.

Intellectualization is a process in which events are analyzed based on remote, cold facts and without passion, rather than incorporating feeling and emotion into the processing.

Despite the fact that a man has lost his farm to a tornado, he analyzes his options and leads his child to safety.

A man responds to the death of his wife by focusing on the details of day care and operating the household, rather than processing the grief with his children.

Projection refers to the unconscious rejection of emotionally unacceptable features and attributing them to others.

No example. This is considered an immature defense mechanism

A woman who has repressed an attraction toward other women refuses to socialize. She fears another woman will make homosexual advances toward her.

Rationalization consists of justifying illogical or unreasonable ideas, actions, or feelings by developing acceptable explanations that satisfy the teller as well as the listener.

An employee says, “I didn’t get the raise because the boss doesn’t like me.”

A man who thinks his son was fathered by another man excuses his malicious treatment of the boy by saying, “He is lazy and disobedient,” when that is not the case.

Reaction formation is when unacceptable feelings or behaviors are controlled and kept out of awareness by developing the opposite behavior or emotion.

A recovering alcoholic constantly talks about the evils of drinking.

A woman who has an unconscious hostility toward her daughter is overprotective and hovers over her to protect her from harm, interfering with her normal growth and development.

Regression is reverting to an earlier, more primitive and childlike pattern of behavior that may or may not have been previously exhibited.

A 4-year-old boy with a new baby brother temporarily starts sucking his thumb and wanting a bottle.

A man who loses a promotion starts complaining to others, hands in sloppy work, misses appointments, and comes in late for meetings.

Repression is an unconscious exclusion of unpleasant or unwanted experiences, emotions, or ideas from conscious awareness.

A man forgets his wife’s birthday after a marital fight.

A woman is unable to enjoy sex after having pushed out of awareness a traumatic sexual incident from childhood.

Splitting is the inability to integrate the positive and negative qualities of oneself or others into a cohesive image.

No example. Almost always a pathological defense

A 26-year-old woman initially values her acquaintances yet invariably becomes disillusioned when they turn out to have flaws.

Sublimation is an unconscious process of substituting mature and socially acceptable activity for immature and unacceptable impulses.

A woman who is angry with her boss writes a short story about a heroic woman.

The use of sublimation is always constructive.

Suppression is the conscious denial of a disturbing situation or feeling. For example, Jessica has been studying for the state board examination for a week solid. She says, “I won’t worry about paying my rent until after my exam tomorrow.”

A businessman who is preparing to make an important speech is told by his wife that morning that she wants a divorce. Although visibly upset, he puts the incident aside until after his speech, when he can give the matter his total concentration.

A woman who feels a lump in her breast shortly before leaving for a 3-week vacation puts the information in the back of her mind until after returning from her vacation.

Undoing is most commonly seen in children. It is when a person makes up for an act or communication.

After flirting with her male secretary, a woman brings her husband tickets to a concert he wants to see.

A man with rigid, moralistic beliefs and repressed sexuality is driven to wash his hands to gain composure when around attractive women.

Anxiety disorders

Clinical picture

Separation anxiety disorder

Panic disorders

Specific phobias

CLINICAL NAME

FEARED OBJECT OR SITUATION

Acrophobia

Heights

Agoraphobia

Open spaces

Astraphobia

Electrical storms

Claustrophobia

Closed spaces

Glossophobia

Talking

Hematophobia

Blood

Hydrophobia

Water

Monophobia

Being alone

Mysophobia

Germs or dirt

Nyctophobia

Darkness

Pyrophobia

Fire

Xenophobia

Strangers

Zoophobia

Animals

Generalized anxiety disorder

Nursing diagnosis: Ineffective coping related to persistent anxiety, fatigue, difficulty concentrating

Outcome criteria: Patient will maintain role performance.

SHORT-TERM GOAL

INTERVENTION

RATIONALE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Anxiety and obsessive-compulsive related disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access