Chapter 64 Malpositions and malpresentations

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

Malposition and malpresentations of the fetus can occur in both pregnancy and labour. The midwife has a key role in identifying these, using best evidence to inform and support the mother and effective skills to undertake safe management and care. With associated higher rates of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, it is essential that careful attention be given to the diagnosis of malposition and malpresentations in order to maximize fetal outcomes (Baxley 2001, Cheng & Hannah 1993, Hannah et al 2000, Pritchard & MacDonald 1980).

While primarily a practitioner of the ‘normal’, the midwife must be fully conversant with the problems and practicalities that both malposition and malpresentations can present. In such circumstances, skills are often tested to the limit and the midwife’s ability to gain the confidence of the woman and to work effectively with the wider healthcare team is paramount in achieving a safe and successful outcome for both mother and baby (ALSO 2003). In dealing with malpositions and malpresentations of the fetus, the midwife needs to be knowledgeable about the latest evidence or lack of it, that will help to inform a woman’s decisions in relation to her care and provide her with the options available (Evans 2007).

Identifying Malpositions and Malpresentations of the Fetus

Midwives must be able to employ a range of skills to assist them in identifying the fetus in:

Incidence

It is essential that the midwife recognize that a malposition is the commonest cause of non-engagement of the fetal head at term in a primigravida. It is the commonest cause of prolonged labour and mechanical difficulties associated with the birth. Persistent OP position was a significant factor in caesarean section and instrumental deliveries with less than half of the OP labours ending in a spontaneous birth of the baby (Fitzpatrick et al 2001).

Malposition of the Occiput

Occipitoposterior positions occur in approximately 10–25% of pregnancies during the early stage of labour and in 10–15% during the active phase, most of which end normally (Gardberg & Tuppurainen 1994a).

Causes of OPP include the following:

Sutton and Scott (1996) highlighted the use of optimal fetal positioning (see website) in helping women to increase their chances of normal childbirth. Other work suggests that such strategies for reducing persistent OPP at birth may be more complex (Hunter et al 2007) (see website).

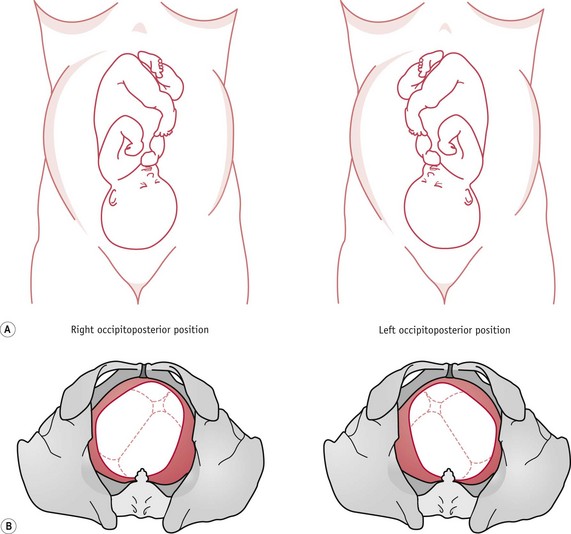

Occipitoposterior positions (Fig. 64.1) throw a heavy responsibility on the midwife, but being overly pessimistic does little to help the mother. Where the labour is progressing satisfactorily, the outcome is likely to be spontaneous rotation to an anterior position followed by a normal vertex delivery.

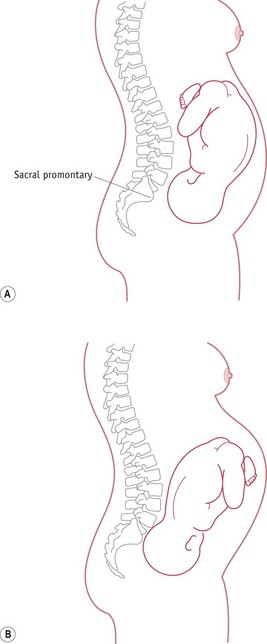

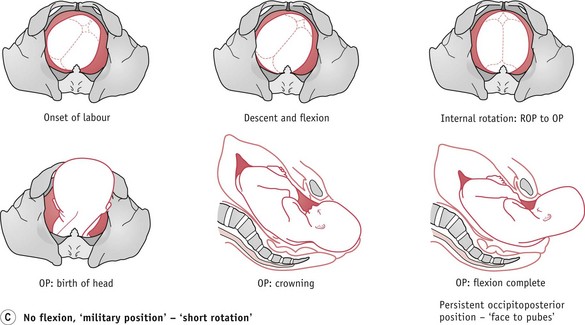

The midwife also needs to be aware of the altered mechanism of a fetus in a posterior position, during which the fetus tends to be in a deflexed attitude, with the anterior fontanelle immediately over the internal cervical os. The fetal spine is towards the forward curve of the maternal lumbar spine, so that the fetus finds it difficult or impossible to adopt a flexed position. As the fetal spine straightens, the fetus tends to ‘square’ the shoulders and raise the chin from the chest, resulting in a deflexed, erect ‘military’ attitude of the fetal head, as shown in Figure 64.2.

Diagnosis of the occipitoposterior position

During pregnancy

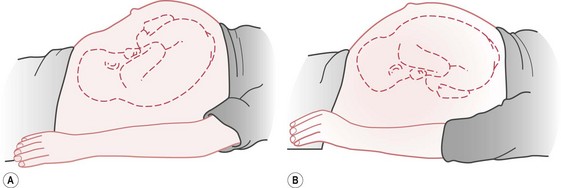

The diagnosis is often made by abdominal examination. On inspection, the abdomen appears flattened, or slightly depressed, below the umbilicus (see Fig. 64.3). On palpation, the fetal head is commonly high. If the fetus is almost occipitolateral, the deflexed head may feel large, because the occipitofrontal diameter is palpated.

The occiput and brow may be felt at the same level at the pelvic inlet, while the fetal back can be palpated out in the flank. If the occiput is markedly posterior, the high head feels small, as the bitemporal diameter is palpated; movements of the fetal limbs can often be seen or easily felt and it may be impossible to feel the back (see Fig. 64.1). The fetal heart sounds can be heard in the midline just below the umbilicus. If the heart sounds are audible in one flank, it suggests that the fetal back is directed towards that side.

During labour

The diagnosis may be made by abdominal examination, though as labour advances, the head may become flexed and engaged. The cephalic prominence of the sinciput can be felt above the pubic bone and on the opposite side to the fetal back. The midwife should be alert whenever the cephalic prominence is felt on the same side as the fetal back and should consider the possibility of a face or brow presentation and seek to exclude these. A deflexed head prior to or in the process of engagement in the maternal pelvis can become extended to a brow, or hyperextended to a face presentation. ‘Coupling’ of contractions is associated with occipitoposterior positions (ALSO 2003). The midwife may identify this phenomenon when she palpates the mother’s abdomen or else on the tocograph tracing if electronic fetal monitoring is in progress.

Progress in labour

Flexion of the fetal head

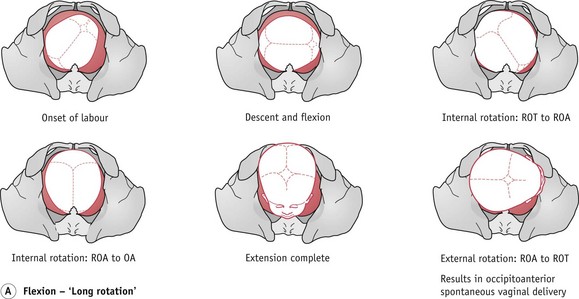

If the head is flexed, labour will probably be completely normal. The engaging diameter is the suboccipitofrontal (10 cm). The occiput reaches the pelvic floor and rotates anteriorly through three-eighths of a circle and the baby is born with the occiput anteriorly (Fig. 64.4).

When the head remains deflexed, it tends to remain high or is slow to engage. Labour is slow to become established, with hypotonic and irregular uterine contractions. However, flexion may improve, and once the head becomes flexed, labour usually accelerates and continues normally, with a long internal rotation and an occipitoanterior birth (Fig. 64.4A).

Persistent occipitoposterior position (POP)

The mechanism is that the lie is longitudinal, presentation vertex and attitude deflexed – the engaging diameter is the occipitofrontal and measures 11.5 cm. The position may be either right or left occipitoposterior and the presenting part is the anterior aspect of the right (ROP) or left (LOP) parietal bone. Descent takes place with deficient flexion and the biparietal diameter of the fetal head is held up on the sacrocotyloid diameter of the maternal pelvis, so that the sinciput becomes the leading part. When the sinciput meets the resistance of the pelvic floor, it rotates forward one-eighth of a circle (Fig. 64.4C). The sinciput passes under the pubic arch and the occiput into the hollow of the sacrum. With good contractions, spontaneous delivery ensues and, with flexion, the occiput sweeps the maternal perineum and, once the glabellar is visible, the brow and face are delivered by extension. The rest of the mechanism follows that of a normal, vertex presentation (see Ch. 37). This is called persistent occipitoposterior position or ‘face-to-pubes’ delivery and is often associated with an anthropoid pelvis (Fig. 64.4C).

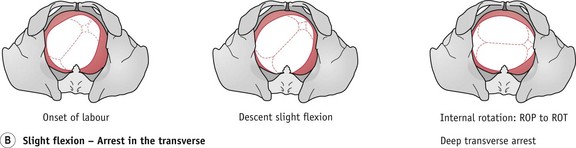

Deep transverse arrest (DTA)

DTA (Fig. 64.4B) may occur if the head remains deflexed. The fetal head may attempt a long rotation, but because of wider diameters and prominence of the ischial spines, it can become caught in the transverse diameter of the obstetric outlet, between the ischial spines.

DTA should be suspected if there is delay in the second stage of labour. On vaginal examination, the sagittal suture is found in the transverse diameter of the pelvis with a fontanelle at each end, close to the ischial spines. In such circumstances, appropriately skilled midwifery or medical assistance should be obtained and, with the use of vacuum extraction (ventouse), the fetal head may be rotated to an anterior position and delivered. Manual rotation of the occiput may also be considered. The midwife should be knowledgeable about this procedure (NMC 2008), and needs to explain the procedure fully to the woman, obtaining informed consent (see website). This should not delay summoning additional assistance.

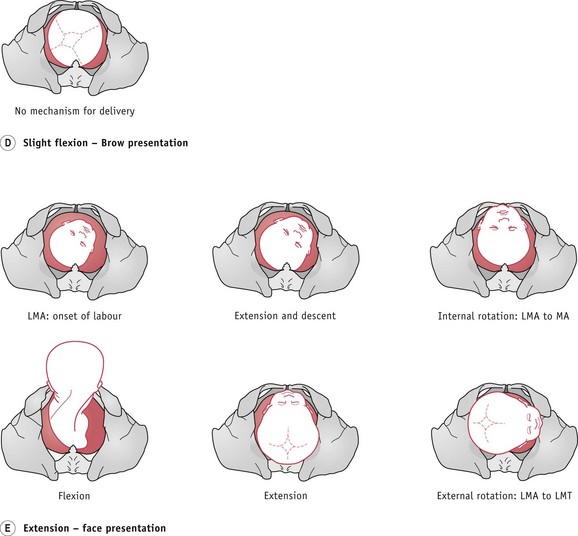

Extension of the fetal head

It is possible that the fetal head may either be in a slightly extended position, or may adopt this as labour progresses, resulting in a brow presentation (Fig. 64.4D). Unless the fetus is particularly small or preterm, then it is unlikely that it will be born vaginally. Full extension of the fetal head may lead to a face presentation, which, if mento-anterior, may deliver vaginally (Fig. 64.4E).

Complications of OPP

Midwives need to carefully consider complications that might arise (Table 64.1) and be fully aware of what action should be taken to prevent or minimize these occurring in their management and care of a woman whose baby is in an occipitoposterior position.

Table 64.1 Complications of occipitoposterior (OP) position

| Complication | Reason |

|---|---|

| Early rupture of the membranes | Poorly fitting presenting part and uneven pressure on the forewaters |

| Cord prolapse | As with any ill-fitting presenting part, the membranes tend to rupture early and the cord may prolapse |

| Prolonged labour | This is associated with a deflexed head, poorly fitting presenting part and misaligned fetal axis pressure. A slightly contracted pelvis may compound this. Hypotonic and inefficient or over-efficient uterine contractions may result. In such circumstances, the development of either fetal or maternal distress is more likely and operative intervention and anaesthesia are often necessary. Postpartum haemorrhage is therefore an added risk |

| Retention of urine | This may occur with prolonged labour and the pressure on the urethra that results from the wider diameters of the OP position |

| Premature expulsive effort | The wider diameter of the OP position results in pressure on the sacral nerves and the woman may feel the need to push before full dilatation of the cervix. Early distension of the perineum and dilatation of the anus can also occur while the head is still high |

| Infection | This is more likely because of early rupture of the membranes, especially if labour is prolonged, and can be compounded by an increased number of vaginal assessments |

| Trauma to the mother’s soft tissues | The risk of trauma is increased with the wider diameter of the OP position. When this is persistent, the biparietal diameter and large occiput distend the maternal perineum. Instrumental delivery may also increase the risk of maternal trauma |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder or postnatal depression | Prolonged, difficult, painful and traumatic labour might result in mental ill-health. This can be exacerbated when the mother has no control over events and is not involved in decision-making. This, together with maternal exhaustion and an unsettled baby, may lead to difficulty in maternal–infant bonding |

| Maternal exhaustion | In prolonged labour, maternal exhaustion may follow the birth |

| Unsettled or difficult-to-feed infant | In an OP position and a prolonged labour, the baby’s head will have been compressed in an unnatural angle, resulting in discomfort and pain |

| Fetal intracranial haemorrhage | Upward moulding of the fetal skull may lead to stretching and damage of the tentorium cerebelli and consequent tearing of the great vein of Galen, resulting in haemorrhage and intracranial damage |

| Increased perinatal mortality and morbidity | This might result from cord prolapse, prolonged labour, instrumental delivery, infection and intracranial haemorrhage, and is increased because of hypoxia and birth trauma |

Malpresentations of the Fetus

Breech presentation

Breech presentation is common before 37 weeks’ gestation, with a suggested incidence of 15% at 29–32 weeks’ gestation reducing to 3–4% at term (Hannah et al 2000, MIDIRS 2008). One fetus in four will present by the breech at some stage in pregnancy. In preterm labour it is not surprising to find the breech presenting and these infants comprise a quarter of all babies born by the breech. However, by the 34th week of pregnancy, the majority will have turned to a vertex presentation.

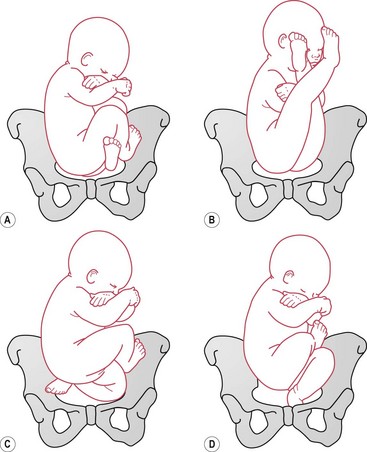

Types

Four types of breech presentation are described (Fig. 64.5). They are determined by the way in which the fetal legs are flexed or extended, and these have implications for the birth.

There is a higher perinatal mortality and morbidity rate with breech presentation, which is largely due to prematurity and congenital abnormalities of the fetus, as well as birth asphyxia and birth trauma (Cheng & Hannah 1993, Hannah et al 2000). The clinical setting, failure to respond to delay and lack of clinical experience may also contribute to poorer outcomes (Kotaska et al 2009).

In providing care, the midwife needs to be conversant with the latest developments surrounding the management and optimal mode of delivery. While the outcomes of the ‘Term Breech Trial’ have dominated the discourse around the mode and management of breech births (Hannah et al 2000) and significantly influenced practice in the United Kingdom and abroad, the evidence is at best uncertain, conflicting and contradictory (Glezerman 2006, Goffinet et al 2006, Hofmeyr & Hannah 2003, Kotaska 2004, Kotaska et al 2009, Van Idderkinge 2007, Waites 2003, Whyte et al 2004).

However, as Shennan & Bewley (2001) point out, the need to provide expertise in vaginal breech delivery will not disappear. Some women present too late, even when a policy of planned caesarean section is in place, and some women will reject the choice of a planned caesarean section and choose to have a vaginal breech birth in either the hospital or home setting because of personal, cultural or religious reasons.

Causes

The fetus may adopt the breech position for a variety of reasons, though the true cause is often unknown. Waites (2003) found that in most cases no single cause can be identified, and it may result from a random occurrence (Bartlett & Okun 1994). The most common cause is likely to be a ‘benign error of orientation’ in which the fetus sits in the breech for no known cause and without any obvious abnormalities. Other causes include:

Table 64.2 Causes of breech presentation

| Primigravidae | Firm abdominal and uterine muscles may prevent flexion of the fetal legs, especially when they are already extended. |

| Uterine anomalies | Bicornuate uterus may restrict fetal movement. Previous breech birth may also be strongly associated with a uterine anomaly. |

| Oligohydramnios | Reduced liquor volume restricts the ability of the fetus to turn in the uterus. The condition may also be associated with fetal anomalies and fetal compromise. |

| Placental location | Placenta praevia may prevent the fetal head from fitting into the lower uterine segment and entering the pelvis. A placenta situated in one or other cornua of the uterus reduces the breadth of space in the upper segment and can lead to a breech presentation. |

| Uterine fibroids |