Chapter 70 Grief and bereavement

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

With better antenatal care and advances in technology, childbirth is now relatively safe, and the birth of a child is usually a cause for celebration and joy rather than as in Dickens’ time, when childbirth itself held significant dangers for mother and baby (see Fig. 70.1). Sadly, even now, some babies do die – there were 3603 stillbirths and 2380 neonatal deaths recorded in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2006 (Lewis 2007, ONS 2006). In addition, it is estimated that 20% of confirmed pregnancies end in miscarriage before 20 weeks’ gestation.

It has only been in the last 15–25 years that the importance of grieving in achieving a healthy long-term outcome has been recognized. Research at the Tavistock Clinic in London has shown that, following stillbirth, bereaved mothers may suffer lifelong repercussions, including hypochondria, phobias and disturbances in relationships (Lewis & Bourne 1989). Appropriate professional help and support throughout the period are essential. Recognizing and responding to the parents’ feelings, sensing what they need and helping them to make informed choices are the challenges for professionals involved in caring for these parents before, during and after the birth of their baby (Schott et al 2007).

Therapeutic use of ourselves

As individuals we naturally tend to turn away from looking at painful things, yet it is only in looking at ourselves that we can grow and ultimately help others. When a baby dies at or soon after birth, the exposure to the parents’ grief, sadness and pain may remind us of our own previous losses. Midwives themselves may have experienced pregnancy loss, or had difficulty in achieving motherhood, and this can impact on their feelings and experience of caring for women and families who also lose babies (Bewley 2010).

Looking after ourselves as professionals

Support and training for midwives working in partnership with families

Bereavement skills training and support should be an intrinsic part of maternity care, whatever the setting (Schott et al 2007). Using counselling and listening skills is an essential part of the professional’s role and requires training, enabling midwives to care effectively when managing the death of a baby.

It is important that the midwife is aware of:

Understanding loss and grief

There are many theories explaining the grieving process, including Bowlby’s (1980) attachment theory; Kubler-Ross (1970) and Parkes’ (1972) series of predictable grief reactions which make up stages or phases of the grief response; and Worden’s (1991) ‘tasks of mourning’.

These tasks of mourning are useful as a framework for understanding the grieving response following the death of a baby. Worden (1991) stresses that mourning, defined as the emotional process that occurs after a loss, is an essential and necessarily painful healing process. As with healing after physical injury, the process can be delayed or go wrong. The midwife has a significant part to play in helping parents begin to accomplish in particular the first two of the following tasks:

Accepting the reality of the loss

Midwives can help enable parents to gradually face reality. Being sensitive to parents’ needs, discussing what other parents have valued, offering choices, such as seeing and holding their dead baby, being involved as much as possible in the preparations for the funeral, and observing rituals and traditions, all help to make what has happened real. Families from different faiths need support for the mourning rituals appropriate to their culture (Thomas 2001, Schott et al 2007, CBC 2007d).

Working through to the pain of grief

As denial and numbness gradually subside, the bereaved parents usually experience the full impact of what has happened. Intensely painful feelings may last many weeks or months. This normal reaction to an abnormal event can be overwhelming as they think about what could have been and what the future now holds. Bereaved mothers are often incapable of thinking about anything or anybody else and are consumed with their child, themselves and how they feel. Painful reminders get in the way and are all around them. Innocent comments may get misinterpreted and cause distress and irritability. Susan Hill (1990), a writer and bereaved mother, eloquently described her extreme sensitivity after the death of her baby Imogen as ‘like having one skin less’, and appreciated the professionals who treated her gently.

The importance of the loss

When a baby lives only a short time or dies before birth, because of miscarriage, termination for fetal anomaly or stillbirth, a common assumption is that the loss is not as significant. Pregnancy is a time of anticipation and many parents, particularly mothers, develop a strong bond with their baby long before it is born (Fig. 70.2). When a baby dies, parents grieve for all they had hoped and the lost opportunity of getting to know their child in a future they had planned together.

The midwife can also help prepare the woman for reactions and feelings that she might experience during the pregnancy and birth of this baby, which might include mixed feelings at the birth, and high levels of anxiety concerning the baby’s wellbeing and survival (Caelli et al 1999, Hunfeld et al 1997). The healthcare team can be alert to this mother’s needs, and ensure that support systems are available during the pregnancy and puerperium (Thomas 2001, Schott et al 2007). Bereaved mothers may be inclined to develop postnatal depression, particularly in cases of complicated grief.

Different parental responses in bereavement

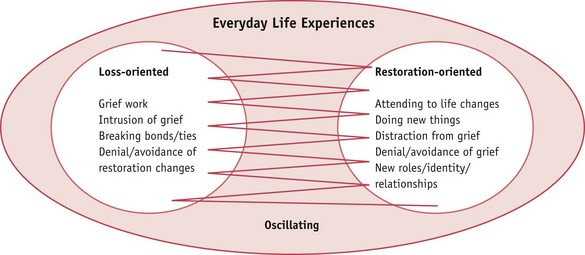

Grief is solitary – even when a couple are grieving, each parent can feel alone in his or her grief, and normal patterns in relationships may become disrupted. As a father’s and mother’s needs are different, they may find they are unable to communicate with one another, to express the awfulness of their feelings. Women naturally tend to be more loss-oriented and focus on their loss and the emotions they are experiencing. They need memories and to constantly recall, be reminded of and talk about their baby who has died. Men are generally more restoration-oriented – they want things to return to normal and prefer to look to the future. Although they feel the loss, it is a loss not to be acknowledged (Puddifoot & Johnson 1997) and this response may be interpreted by their partner, and others, as being uncaring and less interested in their baby. The dual process model of grieving (Stroebe & Schut 1999) illustrates the way bereaved people engage in both loss-oriented and restoration-oriented grieving behaviour and oscillate in healthy grieving between the two behaviours (Fig. 70.3).

Figure 70.3 A dual process model of coping with loss.

(From Stroebe and Schut, 1999, with permission.)

Supporting parents

Women and men say that the most supportive care is when professionals are able to help and encourage parents to ‘parent’ (CBT 2003a, 2003c, CBC 2007a), to be involved with their baby before and after death.

Both parents need support and both need information, though it should be remembered that it is often difficult for distressed parents to absorb and understand what they are told. It is useful to ask the parents to explain to you what they have understood. They may want more information about their baby’s condition or to know more about the reason for their baby’s death, and so any help the midwife can provide in obtaining this information will be welcomed (Schott et al 2007).