5 Analgesia, Sedation, and Neuromuscular Blockade

Pearls

• Analgesia entails assessment and treatment of pain; sedation entails assessment and treatment of agitation; neuromuscular blockade entails pharmacologic inhibition of voluntary muscle movement.

• Analgesia often improves agitation, but does not necessarily provide sedation; sedation often improves pain, but does not necessarily provide analgesia; neuromuscular blockade provides neither analgesia nor sedation, and should never be induced without first ensuring adequate levels of both analgesia and sedation.

• Most critically ill children experience some degree of pain and agitation: optimal nursing care of critically ill children asks how best to provide appropriate analgesia and sedation, not whether analgesia or sedation should be provided.

• Pain and agitation are usually dynamic processes. Nurses should perform appropriate assessments to monitor pain, agitation, and effectiveness of interventions; reassess patients regularly using consistent tools and modify interventions as needed.

• Change in pharmacologic analgesia and sedation to different agents, or to different routes of administration, requires equipotent conversion to ensure ongoing efficacy and to prevent inadequate or excessive dosing.

• All opioid analgesics and many systemic sedatives can induce physiologic tolerance, and should be weaned gradually after prolonged administration to prevent withdrawal. Appropriate use of these agents does not cause addiction, and they should not be avoided because of such concern.

Introduction

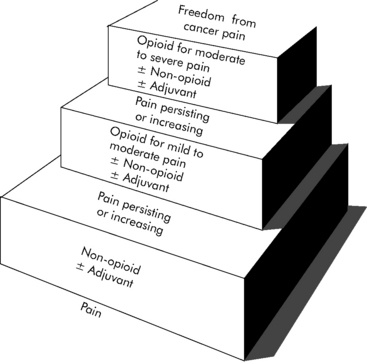

Pain and agitation are common in critically ill patients. As our understanding of these processes in critically ill children has evolved, we now recognize the vital importance of appropriate analgesia and sedation in such patients.48 In 1986, the World Health Organization first published its Analgesic Ladder for the management of cancer pain (Fig. 5-1). This paradigm and others like it are now widely accepted as guidelines for analgesia and sedation in all patients. Despite such advances, considerable progress remains to be made. Caregiver education should enhance awareness of the crucial need for appropriate analgesia and sedation in critically ill children. Practice patterns must continue to change to include appropriate analgesia and sedation as essential components of pediatric critical care. Ongoing research must continue to explore the nature of these complex processes and their optimal management.

(With permission from: Cancer pain relief and palliative care in children. Companion volume to: Cancer pain relief, with a guide to opioid availability. Geneva 1998, World Health Organization. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241545127.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2010.)

All pharmacologic agents used to provide analgesia, sedation, and neuromuscular blockade have potential side effects and complications, particularly a risk of respiratory depression and cardiovascular compromise. Risk may be higher in pediatric patients, especially when they are developmentally immature or medically fragile.54 Ongoing patient monitoring is essential.

Anatomy, physiology, and embryology of pain

Nociception

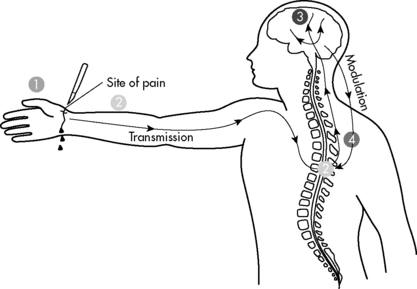

Nociception is the normal process through which pain is experienced (Fig. 5-2). Nerve pathways underlying pain sensation in humans are fully developed at term (see Anatomy, Physiology and Embryology of Pain in the Chapter 5 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Most pain in critically ill children is nociceptive in nature and tends to respond to conventional antinociceptive analgesics.

Perception refers to the complex and poorly understood process by which pain becomes a conscious experience. Perception includes the physical sensation of noxious stimuli and the entire conscious experience of such stimuli with attendant emotional and behavioral components.22 Perception is a unique process in each patient and is affected by age, developmental maturity, and underlying medical condition. Perception is also a highly dynamic process, varying among patients and in the same patient at different times.

Modulation refers to modification of pain by other nervous system input. Modulation can ameliorate or exacerbate pain and may explain some of the tremendous variability in subjective pain experience, especially in children. Modulation is a highly complex process and can take place at any point in transduction, transmission, and perception. A particularly important modulatory pathway is the descending pain system, with nerve axons projecting from the brainstem and other supraspinal centers to various laminae of the spinal cord. These descending fibers inhibit transmission of painful sensory stimuli, enhancing analgesia. Anxiety can also modulate pain, causing increased sensitivity to pain and resultant pain-related disability, particularly in chronic pain.40

Classification of Pain

Pain is often classified temporally as acute or chronic, anatomically as somatic or visceral, and pathophysiologically as nociceptive or neuropathic (Table 5-1). Such classifications are not mutually exclusive; clinical presentations may suggest considerable overlap, and clear distinctions are not always possible.

Table 5-1 Classifications of Pain

| Temporal Classification* | |

| Acute Pain | Chronic Pain |

| Expected duration, often hours to days | Prolonged duration, often weeks to months |

| Somatic or visceral | Somatic or visceral |

| More commonly nociceptive | Nociceptive or neuropathic |

| Anatomic Classification | |

| Somatic Pain | Visceral Pain |

| Originates in somatic innervation of periphery | Originates in autonomic innervation of viscera |

| Acute or chronic | Acute or chronic |

| Nociceptive or neuropathic | Nociceptive or neuropathic |

| Pathophysiologic Classification | |

| Nociceptive Pain | Neuropathic Pain |

| Result of normal nervous system function | Associated with nervous system dysfunction |

| Acute or chronic | More commonly chronic |

| Somatic or visceral | More commonly somatic |

| Typically responds to conventional analgesics | Responds poorly to conventional analgesics |

* Classifications are not mutually exclusive: clinical presentations frequently suggest considerable overlap, and clear distinctions are not always possible.

Temporal Classification of Pain

Pain can be classified temporally as acute or chronic. Acute pain persists for an expected duration, often hours to days. Many medical illnesses and surgical procedures are associated with acute pain of fairly predictable duration with subsequent resolution. Acute pain can be somatic or visceral (see section, Anatomic Classification of Pain). Acute pain in children is most commonly nociceptive, although acute neuropathic pain may be encountered.

Neuropathic Pain

Phantom or deafferentation pain is a variant of neuropathic pain associated with central nervous system dysfunction following disruption of peripheral sensory input. Phantom pain can occur long after denervation of affected areas and may persist chronically or even permanently. Phantom pain may be seen following traumatic or surgical amputation and has even been described after dental extraction.46 The pathophysiology of phantom pain is complex and incompletely understood.

Patient assessment

Recognition and treatment of pain and agitation can be particularly challenging in the absence of reliable objective quantitative assessments on which to base clinical decisions. Patient descriptions can guide analgesic and sedative interventions. However, even verbal children may find it difficult to express this information, particularly in the setting of critical illness. Children may be nonverbal or otherwise incommunicative secondary to age, developmental immaturity, medical illness, surgical procedures, or interventions such as intubation. Caregivers must recognize patient behaviors or behavioral patterns that provide clues to the presence, location, severity, and even cause of pain and agitation, and must monitor changes to guide therapy. No single objective assessment strategy will be sufficient or appropriate for every patient in every setting.31

Caregiver fears and beliefs may also hinder adequate analgesia and sedation. Caregivers may fear providing unnecessary analgesia or sedation, particularly controlled substances. They may misinterpret regulations and legal requirements associated with these medications, or may fear promoting patient addiction. In terminal or palliative care settings, caregivers may fear hastening or even causing death. These issues must be addressed within the healthcare team (see Chapter 3).

Assessment Tools

Subjective Patient Report

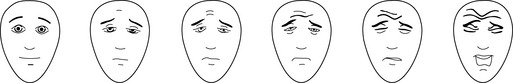

Assessment tools relying on a subjective patient report ask the patient to indicate status on a continuum. Pain scales commonly range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum possible pain); sedation scales vary more widely. Verbal children who are able to count may simply be asked to indicate their pain score on a 0-10 scale. Interactive but nonverbal children, or children unable to count, may be asked to indicate their pain score on a continuum scale using colors, pictures of children, or drawings of faces that represent degrees of distress. Three such pain assessment tools commonly used in pediatric practice are the Oucher! (see Evolve Fig. 5-1 in the Chapter 5 Supplement on the Evolve Website), the McGrath Faces Pain Scale, and the Hicks Faces Pain Scale-Revised (Fig. 5-3). See Patient Assessment in the Chapter 5 Supplement on the Evolve Website.

Objective Caregiver Evaluation

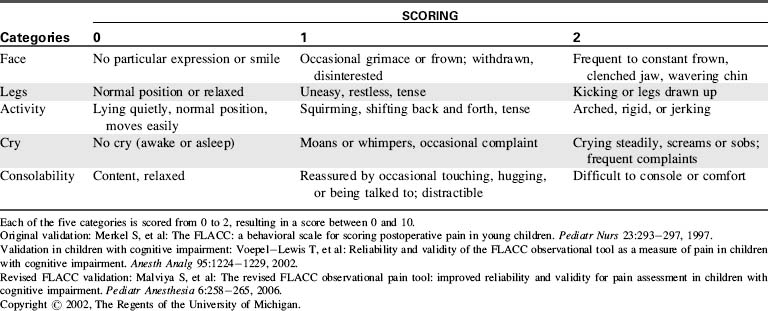

Many assessment tools for objective caregiver evaluation of pain and agitation have been developed for and validated in the pediatric setting. Examples include the FLACC scale (characterizing the patient’s Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability using specific options) for assessment of pain in nonverbal children (Table 5-2), the COMFORT scale (assessing overall comfort by evaluating specific physical characteristics) for assessment of agitation in critically ill children, and the State Behavioral Scale for assessment of agitation in infants and children during mechanical ventilation.19 Examples of these tools may be found in Evolve Fig. 5-2 in the Chapter 5 Supplement on the Evolve Website. Additional tools have been reported for use in specific patient populations or particular clinical settings.50

Management Planning

With appropriate intervention, most critically ill children should experience little pain and minimal distress. Following comprehensive patient assessment, an appropriate management plan is developed to address patient pain and agitation.48 The goals of any management plan should be to maximize analgesia and sedation, minimize side effects and complications, and if possible aid in diagnosis and treatment of underlying critical illness. Ideally, all caregivers should be involved in development of this plan and should be aware of planned interventions. During and after interventions, caregivers must perform regular and periodic patient reassessment to evaluate patient response and guide further interventions. Management must be individualized for each patient, combining nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions as appropriate.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Cognitive and Behavioral Modalities

Music Therapy

Music therapy can provide both distraction and relaxation in children. It has been used effectively in the operating room, postanesthesia care unit, neonatal critical care unit,4,32 and oncology ward. Music choice should be based on patient age, culture, and preference, guided as necessary by parents, other family members, and friends. Listening to music through headphones offers the added benefit of masking chaotic auditory stimuli.

Systemic analgesics

Numerous systemic analgesics are available for use in children (Table 5-3). Systemic analgesics can have a wide range of physiologic effects, particularly in critically ill children. Knowledge of the agents being administered is essential for optimal efficacy and patient safety. Nurses must be aware of expected clinical effect, usual time of onset, likely duration, and potential side effects of each agent administered. Medications ordered on an as-needed basis are effective only when given appropriately with ongoing and recurring patient assessment. Frequent requirement for a drug ordered only on an as needed basis should prompt consideration of scheduled administration and additional interventions. Intramuscular injection is painful and absorption variable; it should be avoided except perhaps in the setting of difficult intravenous access. Although many systemic analgesics can produce sedation, they should not be used primarily for this purpose.

| Drug | Dose | Comments |

| Acetaminophen | ||

| Acetaminophen and NSAIDs are generally synergistic and may be given together without need to alternate or stagger doses. | ||

| Acetaminophen | Load: 20 mg/kg PO (maximum 1000 mg), then | Good antipyretic; hepatic toxicity with overdose |

| Main: 15 mg/kg PO (maximum 1000 mg) q4-6 h | Loading dose especially useful for procedural or perioperative analgesia | |

| Load: 40 mg/kg PR (maximum 1300 mg), then | FDA now advises maximum single adult dose of 650 mg for over-the-counter use | |

| Main: 20 mg/kg PR (maximum 1300 mg) q4-6 h | ||

| Maximum 4 g/24 h PO/PR | ||

| Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) | ||

| Acetaminophen and NSAIDs are generally synergistic, and may be given together without the need to alternate or stagger doses. | ||

| Choline magnesium trisalicylate | 10 mg/kg PO/PR (maximum 1500 mg) q6-8 h | Only NSAID without platelet dysfunction |

| Maximum 4 g/24 h PO/PR | No association with Reye syndrome | |

| Ibuprofen | 10 mg/kg PO/PR (maximum 800 mg) q6-8 h | Good antipyretic (IV dose: 5 mg/kg may be used for antipyretic) |

| IV: 10 mg/kg (for pain) | ||

| Maximum 3200 mg/24 h PO/PR | IV formula recently approved analgesic in adults | |

| Ketorolac | 0.5 mg/kg IM/IV (maximum 30 mg) q6 h | Potentially significant platelet dysfunction |

| Total therapy must be <5 days | ||

| Lower Potency Oral Opioids | ||

| Recommended doses are for initial administration in opioid-naïve patients: titration to clinical effect is required; recommended initial opioid doses should typically be reduced 35% to 50% in neonates and young infants. | ||

| Codeine | 1 mg/kg PO q4 h (adult dose, 30-60 mg) | Tablet and liquid preparations typically in combination with acetaminophen |

| High incidence of gastrointestinal side effects | ||

| Hydrocodone | 0.2 mg/kg PO q4 h (adult dose, 10-15 mg) | Tablet and liquid preparations typically in combination with acetaminophen or NSAID |

| Moderate incidence of gastrointestinal side effects | ||

| Sustained-release product available as antitussive, under study as analgesic | ||

| Oxycodone | 0.1 mg/kg PO q4 h (adult dose, 5-10 mg) | Tablet preparations with or without acetaminophen or NSAID |

| Liquid preparations contain only oxycodone | ||

| Low incidence of gastrointestinal side effects | ||

| Sustained-release product available for chronic therapy | ||

| Higher Potency Opioids | ||

| Recommended doses are for initial administration in opioid-naive patients: titration to clinical effect is required; recommended initial opioid doses should typically be reduced 25% to 50% in neonates and young infants; PCA demand dose typically q 8-10 min for patient-controlled analgesia, q 15-60 min for nurse or parent-controlled analgesia. | ||

| Fentanyl | 5-15 mcg/kg PO (adult dose 400 mcg) | Dosing interval for oral preparation not well defined |

| 0.5-2 mcg/kg IV (adult dose 100 mcg) q 1 h | ||

| Infusion 0.5-2 mcg/kg per hour (adult dose 100 mcg/h) | Rapid IV infusion may cause chest wall rigidity in infants | |

| Patch 25 mcg = 1 mg/h IV morphine | ||

| PCA demand dose 0.5-1 mcg/kg IV (adult dose 50-100 mcg) | Tachyphylaxis common | |

| PCA basal 0.5-1 mcg/kg per hour IV (adult dose 50-100 mcg/h) | Transdermal patch not for acute management | |

| Hydromorphone | 20-40 mcg/kg PO (adult dose 2-4 mg) q 3 h | Sustained-release oral product under study as analgesic |

| 10-20 mcg/kg IM/IV/SC (adult dose 1-2 mg) q 3 h | ||

| Infusion 4 mcg/kg per h (adult dose 0.2-0.3 mg/h) | Less histamine release than morphine | |

| PCA demand dose 4 mcg/kg IV (adult dose 0.2-0.3 mg) | ||

| PCA basal 4 mcg/kg per hour IV (adult dose 0.2-0.3 mg/h) | ||

| Meperidine | 0.25-0.5 mg/kg IM/IV/SC (adult dose 12.5-25 mg) | Doses for treatment of shivering |

| Infusion/PCA not recommended | Neurotoxic metabolite may induce seizures | |

| No hepatobiliary advantage over any other opioid | ||

| No longer recommended as primary analgesic | ||

| Methadone | 0.1 mg/kg PO (adult dose 5-10 mg) q6-12 h | Useful for chronic therapy Treatment of addiction must be in federally licensed facility |

| 0.05 mg/kg IV (adult dose 2.5-5 mg) q6-12 h | ||

| Infusion/PCA not generally used | ||

| Morphine | 0.3 mg/kg PO (adult dose 15-30 mg) q3 h | Sustained-release oral product available for chronic therapy |

| 0.05-0.1 mg/kg IM/IV/SC (adult dose: 5-10 mg) q3 h | ||

| Infusion 0.02 mg/kg per h (adult dose 1-1.5 mg/h) | Potentially significant histamine release | |

| PCA demand dose, 0.02 mg/kg IV (adult dose 1-1.5 mg) | ||

| PCA basal 0.02 mg/kg per hour IV (adult dose 1-1.5 mg/h) | ||

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; h, hour; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; Load, loading dose; Main, maintenance dose; mcg, microgram; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PO, by mouth; PR, by rectum; q, every; SC, subcutaneous.

Nonopioid Analgesics

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is widely used as an analgesic and an antipyretic. It can provide complete analgesia for mild to moderate pain and may reduce opioid requirement in moderate to severe pain, particularly when given on a scheduled basis. Acetaminophen is not an NSAID. Although it is a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, it has virtually no antiinflammatory activity, and therefore has few gastrointestinal, renal, or hematologic side effects. The primary toxicity of acetaminophen is hepatic, seen with both acute and chronic overdose, although renal toxicity has been described.42

Acetaminophen is at least as effective an analgesic as codeine,12 and it is synergistic with NSAIDs.52 Acetaminophen and NSAIDs can be given simultaneously without need to alternate or stagger doses. As with most nonopioid analgesics, acetaminophen demonstrates a ceiling effect: exceeding recommended doses does not significantly improve analgesia and increases risk of side effects and toxicity. Recently, an FDA advisory committee recommended the maximum single adult dose for over-the-counter products be reduced to 650 mg because of risk of hepatic injury.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at