Nancy Ridenour and Yvonne Santa Anna “Law is order, and good law is good order.” —Aristotle Public policy formation in the United States often appears to be indecisive and slow, and it can be difficult for the casual observer to distinguish the subtleties of the process. These nuances require that the observer select a conceptual model of policymaking to assist in understanding the specifics of the policymaking process—that is, why a particular proposal is enacted or defeated. Chapter 6 set forth several models for policy analysis. These can clarify how an issue is placed on the formal agenda for authoritative decision-making. Nurses who understand this process can better influence the development of sound health policies for their patients, their patients’ families, and the profession of nursing. This chapter will describe the path by which a bill becomes a federal or state law in the U.S., with primary emphasis on federal processes. The legislative path differs only slightly between the federal and state levels and from state to state. Only a member of the U.S. Congress (or of a state legislature) can introduce bills, though the idea for a bill can come from anyone, including constituents. A legislator can introduce any one of several types of bills and resolutions by simply giving the bill to the clerk of the house or, in Congress, placing the bill in a box called the hopper (Congressional Quarterly, 2008). In the U.S. Senate, a senator can postpone the introduction of another senator’s bill by 1 day by voicing an objection. Legislation is often introduced simultaneously in the Senate and the House of Representatives as a pair of companion bills. A member of Congress or state legislator who understands the legislative process in depth can contribute more to either the passage or defeat of a bill than one who is an expert only on its substance. However, the numerous players involved (the executive branch, the legislature, constituents, and special interest groups) and the complexity of the legislative process make it far easier to defeat a bill than to pass one. Every bill introduced in Congress faces a 2-year deadline; it must pass into law by then or die by default. Box 65-1 provides an overview of the various types of bills that can be introduced by members of Congress. Legislators introduce bills for a variety of reasons: to declare a position on an issue, as a favor to a constituent or a special interest group, to obtain publicity, or for political self-preservation. Some legislators, having introduced a bill, claim that they have acted to solve the problem that motivated it but do not continue to work toward enactment of the measure, blaming a committee or other members of the legislature if no further action is taken. Passage of a bill requires that at critical points in the policymaking process “a problem is recognized, a solution is available, the political climate makes the time right for a change, and the constraints do not prohibit action” (Kingdon, 1984, p. 93). Although meeting these conditions helps a bill to rise on the decision agenda, nothing can guarantee enactment. Nurses can influence the introduction of bills as constituents and as members of professional associations that lobby Congress. They can call attention to problems in funding health care, such as the need for expanded services for uninsured children, the need for long-term care coverage under Medicare, or the need to increase reimbursement for nursing services. Legislators like to work with organized groups that have strong positions on a bill, such as the American Nurses Association, American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties, or the state nurses associations. Frequently, associations are asked to assist in drafting legislation and in lobbying members of the legislature. Coalitions of interested organizations are created to present a united front, a clear message, and a strong constituency to persuade legislators to support a particular bill (see Chapter 86). Enactment, if achieved at all, may take several legislative sessions. Identifying the appropriate sponsor to introduce a bill is critical to its success. In selecting a primary bill sponsor, it is best to ask a member of a committee that has jurisdiction over the issue you wish to have addressed. For example, in the U.S. Senate, the Finance Committee has jurisdiction over the Medicare program and decides which Medicare-related legislation is sent to the full Senate for a vote. Legislation that would address changes in direct reimbursement of nurse practitioners (NPs) or nurse anesthetists under Medicare would be less likely to be tabled (i.e., never acted upon) if a member of the Senate Finance Committee was a primary sponsor of the measure. Committees are centers of policymaking at both federal and state levels. It is in committee that conflicting points of view are discussed and legislation is often refined and amended. Successful committee consideration of bills requires organization, consensus building, and time; only about 15% of all bills referred to committees are reported out for House and Senate consideration. The Senate and House have separate committees with distinct rules and procedures. Committee procedure provides the means for members of the legislature to sift through an otherwise overwhelming number of bills, proposals, and complex issues. Within the respective guidelines of each chamber, committees adopt their own rules to address their organizational and procedural issues. Generally, committees operate independently of each other and of their respective parent chambers (Schneider, 2008). There are three types of committees at the federal level: standing, select, and joint. A standing committee has permanent jurisdiction over bills and issues in its content area. Some standing committees set authorizing funding levels, and others set appropriating funding levels for proposed laws. This two-step authorizing-appropriating process is designed to concentrate the policymaking decisions within the authorizing committee and decisions about precise funding levels within the appropriations committees. A select committee cannot report out a bill and is often created by the leadership to address a special problem or concern. A joint committee consists of members of both the House and Senate. One type of a joint committee is the conference committee, in which members of each chamber and party work together to address differences in their respective bills. In congressional committees, leadership and authority is centered in the chair of the committee. The chair, always a member of the majority party, decides the committee’s agenda, conducts its meetings, and controls the funds distributed by the chamber to the committee (Schneider, 2007). The senior minority party member of the committee is called the ranking minority member (or ranking member). The committee’s subcommittees also have chairs and ranking members. Often, but not always, the ranking member assists the chair with some of the responsibilities of the committee or subcommittee. The committee chair usually refers a bill to the subcommittees for initial consideration, but only the full committee can report out a bill to the floor (Schneider, 2007). For example, the House Ways and Means Committee refers most Medicare bills to the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Health. If the subcommittee wishes to take action on the bill, it usually will schedule at least one hearing to discuss the substance of the proposed legislation. In very unusual circumstances, a few bills will bypass the committee process. This can only happen if the leadership of the majority consents. For example, according to a U.S. House Select Committee on Aging Fact Sheet, “Since the Roosevelt era, major pieces of social legislation, including civil rights reforms and labor reforms, such as the wage and hours bill, were forced to bypass committees of jurisdiction because the committees refused or delayed in allowing the House to consider them” (Pepper & Roybal, 1988, p. 1). In the end, however, committees and subcommittees usually select the bills they want to consider and ignore the rest. Committees thus perform a gate-keeping function by selecting from the thousands of measures introduced in each session those that meet their party’s leadership priorities and that they consider to merit floor debate. Consideration of bills whose content overlaps the jurisdictions of different committees falls to the leader of the chamber to decide. Health care issues, for example, can cut across the jurisdiction of more than one committee. When this occurs in the House, upon advice from the Parliamentarian, the Speaker of the House will base his or her referral decision on the chamber’s rules and precedents for subject matter jurisdiction and identify the appropriate primary committee and other committees for the bill’s referral (Schneider, 2007). The Parliamentarians in both chambers have a key role in advising the member of Congress presiding over a bill on the floor. While a member is free to take or ignore the Parliamentarian’s advice, few have the knowledge of the chamber’s procedures to preside on their own. The primary committee has primary responsibility for guiding the referred measure to final passage. Referrals to more than one committee can have a positive effect by providing opportunities for greater public discussion of the issue and multiple points of access for special interest groups, but this can also greatly slow down the legislative process (Davidson, Oleszek, & Lee, 2007). A committee can handle a bill in any of the following ways (Congressional Quarterly, 2009): To understand the legislative process and to analyze individual pieces of legislation, it is important to know the distinction between authorizing legislation and appropriating legislation. Because a considerable amount of congressional activity is concerned with decisions related to spending money, and because much of this activity has a direct effect on health care and nursing programs, it is especially important for nurses to be familiar with the authorization-appropriation process. Programs and agencies such as the Nurse Education Act, Scholarships for Disadvantaged Students, the National Health Service Corps, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the National Institutes of Health, and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research are all subject to the authorization-appropriation process. Before any of these programs can receive or spend money from the U.S. Treasury, a two-step process must occur. First, an authorization bill allowing an agency or program to come into being or to continue to exist must be passed. The authorization bill is the substantive bill that establishes the purpose of, and guidelines for, the program and usually sets limits on the amount that can be spent. It gives a federal agency or program the legal authority to operate. Authorizing legislation does not, however, provide the actual dollars for a program or enable an agency to spend funds in the future. Renewal or modification of existing authorization is called reauthorization (see Chapter 64). Second, an appropriation bill must be passed. The appropriation bill enables an agency or program to make spending commitments and to actually spend money. In almost all cases, an appropriation bill for an activity is not supposed to be passed until the authorization for that activity is enacted. That is, no money can be spent on a program unless it first has been authorized to exist. Conversely, if a program has been authorized but no money is provided (appropriated) for its implementation, that program cannot be carried out (Schick, 2007). The authorization-appropriation process is determined by congressional rules that, like most congressional rules, can be waived, circumvented, or ignored on occasion. For example, failure to enact an authorization does not necessarily prevent the appropriations committee from acting. If an expired program—for example, the Nursing Education Act—is deemed likely to be reauthorized, it may receive funds. These must be spent in accordance with the expired authorizing language. Today, much of the federal government is funded through the annual enactment of 13 general appropriations bills. Whether agencies receive all the money they request depends, in part, on the recommendations of the authorizing and appropriating committees. Each chamber has authorizing and appropriating committees, and these have differing responsibilities. For federal nursing education and research activities, the authorizing committees are the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The appropriating committee for federal nursing education and research programs are the Senate and House appropriations committees and their subcommittees on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Figure 65-1). Committee consideration of a measure usually consists of three standard steps: hearings, markups, and reports. Hearings can be legislative, oversight, or investigative; each of these types of hearing may be either public or closed (Schneider, 2007). When the committee leadership decides to proceed with a measure, it will usually conduct hearings to receive testimony in support of a measure. From these hearings the committee will gather information and views, identify problems, gauge support for and opposition to the bill, and build a public record of committee action that addresses the measure (Schneider, 2007). Although most hearings are held in Washington, D.C., field hearings in the members’ respective states are also held. Most witnesses are invited to testify before the committee by the chair, who is a member of the majority party and who sets the agenda for the hearing proceedings. The ranking minority member may have an opportunity to request a witness, but it is up to the discretion of the chair to agree to the selection of the witness. Written testimony can also be submitted to the committee by persons who do not have the opportunity to speak their position on a measure in person. Nurses can influence the policymaking process by testifying at bill hearings. Frequently, committees prefer to deal with large, organized groups that have a position on an issue rather than with private individuals. Professional nursing organizations testify on behalf of their members. Congressional hearings are listed in the official House and Senate websites at www.house.gov and www.senate.gov. C-SPAN provides live and recorded coverage of hearings at www.c-span.org. Constituents can influence the committee process by meeting with and writing to members of the committee. Concerns expressed by constituents are given serious consideration. Lobbyists often meet with all members of the committee to express their client’s position on a measure. Professional associations often activate a grassroots network of members, asking them to contact the committee members to request co-sponsorship of, or opposition to, the measure. The hearing process at the state level is similar, as is the importance of an organized approach to presenting testimony. When several representatives of nursing plan to testify on a bill, it is more efficient and effective for them to coordinate their testimony, raising different aspects of an issue rather than repeating the same points. It is also important for various nursing representatives to emphasize those issues where there is agreement; a unified message can strengthen the impression of a powerful coalition. And a hearing room packed with a supportive audience makes a powerful statement to legislators about support for an issue. When legislative hearings are concluded, a subcommittee decides whether to attempt to report a measure. If the chair decides to proceed with the measure, she or he will generally choose to continue with the legislative process to “mark up” the bill. A markup is the committee meeting where a measure is modified through amendments to clean up problems or errors within the measure (Schneider, 2007). A quorum of one third of the committee is required in both chambers to hold a markup session (Schneider, 2007). A markup session can weaken or strengthen a measure. Pressure from outside interest groups is often intense at this stage. Under congressional “sunshine rules,” markups are conducted in public, except on national-security or related issues. After conducting hearings and markups, a subcommittee sends its recommendation to the full committee, which may conduct its own hearings and markups, ratify the subcommittee’s decision, take no action, or return the bill to the subcommittee for further study. The rules of both the Senate and the House dictate that a committee report accompany each bill to the floor. The report, written by committee staff, describes the intent of legislation (i.e., its purpose and scope). It explains any amendments to the bill, and any changes made to current law by the bill; estimates the cost of the bill to the government; sets out documentation for the bill’s legislative intent; and often contains dissenting views on the measure from the minority-party committee members. A committee’s description of the legislative intent of the bill is extremely important, especially for the government agency that will implement and enforce the law. Sometimes the report contains explicit instructions on how the agency should interpret the law in regulations, or the report may be written without great detail. Sometimes an agency will interpret the law narrowly, particularly if it is written vaguely. For example, when certified nurse midwives received reimbursement authority under the Medicare program, the agency chose to reimburse them only for gynecologic services, not for all the services covered by Medicare, which they are legally able to provide. This was a narrow interpretation of the law and was not the intent of Congress. The committee report is also important because it offers those interested in the bill an opportunity to promote or protect their interests. Committee staffs frequently include the report language suggested by special interest groups if it is congruent with the bill. After a bill is reported out of committee, it can be placed on a calendar of chamber business and scheduled for floor action by the leadership of the majority party (Schneider, 2007). If the bill is not controversial, it may be dealt with expeditiously. Otherwise, it is placed on the chamber’s calendar for future consideration. Both the rules governing the calendar on which a bill is placed and the subsequent floor procedures differ between the House and Senate and among state chambers. Box 65-2 compares the House and Senate procedures for scheduling and raising measures.

An Overview of Legislation and Regulation

Influencing the Legislative Process

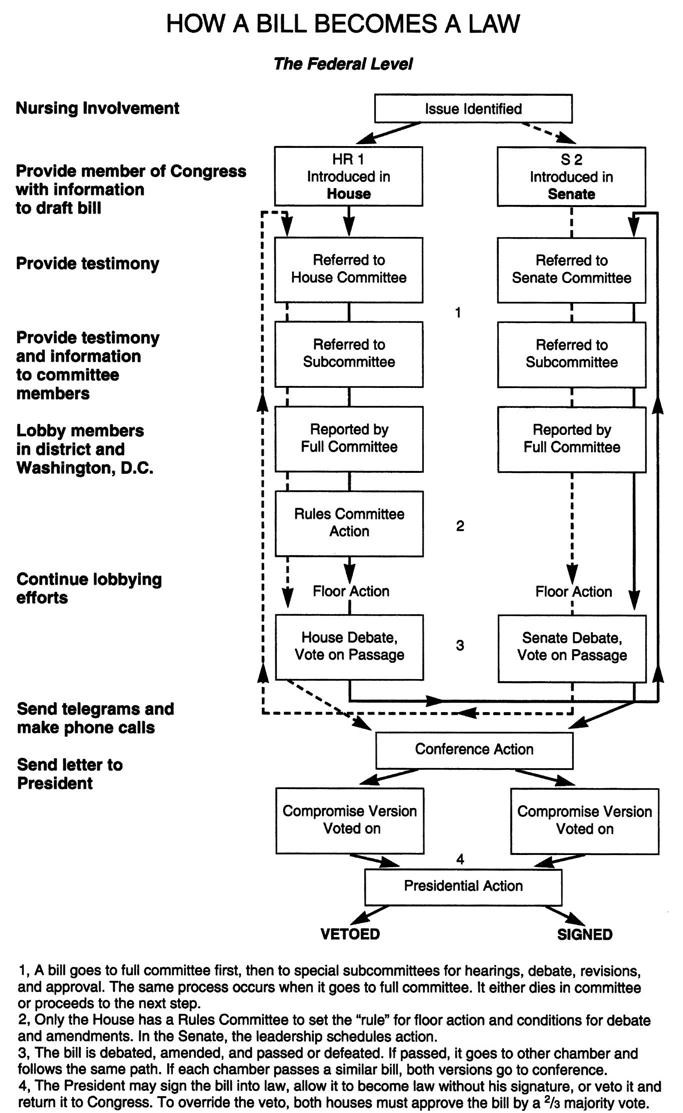

Introduction of a Bill

Influencing the Introduction of a Bill

Committee Action

Authorization and Appropriation Process

Committee Procedures

Hearings.

Markups.

Reports.

Floor Action in the House and Senate

An Overview of Legislation and Regulation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access