Diane M. Doran

- Outcomes-focused knowledge translation provides an approach to knowledge translation that links patient outcomes, measurement, and feedback with research evidence and patient preferences, to encourage evidence-based practice (EBP).

- One mechanism by which outcomes feedback is expected to improve EBP and treatment outcomes involves critical reflection about what is working and what is not working in patient care. A second mechanism by which outcomes feedback is expected to improve treatment outcomes may involve improved communication between the clinician and patient.

- Intuitive reasoning, a relatively automatic form of reasoning, which can stem either from instinctual cognitive processes or from highly practiced, over-learned behavior, is subject to a well-known range of biases and contextual errors. The goal of outcomes-focused knowledge translation is to stimulate rational deliberative reasoning about the patient’s response to health-care intervention and about the most appropriate patient-care interventions.

- Outcomes-focused knowledge translation could be used in combination with other validated approaches for knowledge translation that include attention to the context of care.

Introduction

This chapter describes the conceptual framework for knowledge translation that is known as outcomes-focused knowledge translation (Doran & Sidani 2007). Knowledge translation is defined as “the exchange, synthesis and ethically sound application of researcher findings within a complex system of relationships among researchers and knowledge users” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/7518.html, accessed July 19, 2009). Outcomes-focused knowledge translation provides an approach to knowledge translation that links patient outcomes, measurement, and feedback with research evidence and patient preferences, to encourage evidence-based practice (EBP). It involves four components:

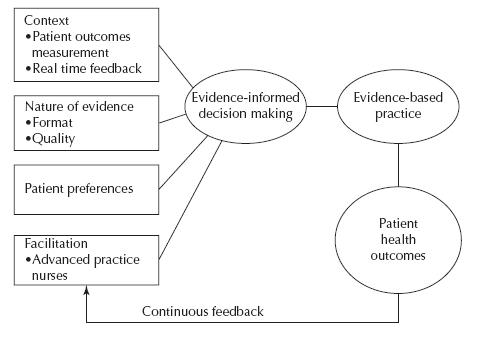

The outcomes-focused knowledge-translation framework was informed by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) model. Figure 4.1 illustrates the framework.

Figure 4.1 Outcomes-focused knowledge-translation framework.

Source: Doran and Sidani (2007). Reprinted with the permission from Blackwell Publishing.

Purpose of the framework

A conceptual framework is described as a set of broad ideas and principles taken from relevant fields of enquiry and used to guide research or practice. It is a set of coherent ideas or concepts organized in a manner that makes them easy to communicate to others. The outcomes-focused knowledge-translation framework was developed to guide knowledge-translation activities by encouraging the uptake of evidence through patient outcomes measurement and feedback and through reflective practice. Its primary target audience is the individual clinician. The individual clinician is a linchpin in the knowledge-translation process because it is the individual clinician who is the ultimate arbiter of decisions related to the care and treatment of patients (Brehaut et al. 2007). With new knowledge in the health sciences being advanced so rapidly, clinical practice has become the most efficient context for learning about new innovations in patient care (Handfield-Jones et al. 2002). We note that a most compelling rationale for EBP is that it offers an approach to foster learning that goes beyond ad hoc needs to true lifelong learning (Spring 2007). We also know that the individual clinician does not practice in isolation but is influenced by the action of others and by the norms, resources, and facilities of the practice environment (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2002). The context of care is most important to the translation of new knowledge. To explore how outcomes should stimulate that learning translation at the clinical level it is helpful to examine in more detail the outcomes-focused knowledge-translation framework, its theoretical foundations, and empirical evidence.

The focus on outcomes

In its bid to increase accountability for the delivery of health-care services, to promote quality improvement, and to measure the impact of nurses within the health-care system, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) instituted data collection on a core set of patient outcomes that are sensitive to the practice of nurses (Pringle & White 2002). This initiative, which is known as Health Outcomes for Better Information and Care (HOBIC), involves the collection of outcomes data by nurses at the time patients are admitted to health-care services and at discharge. HOBIC consists of a set of generic outcomes relevant for adult populations in acute care, home care, long-term care, and complex continuing care settings. The HOBIC outcomes include functional status, symptoms (pain, nausea, dypsnea, fatigue), pressure ulcers, falls, and therapeutic self-care. Staff nurses are instructed in how to collect the outcomes data using standardized tools and in how to record their assessments as part of routine documentation. This Ontario initiative is highlighting the importance of patient outcomes data and is making it much more accessible to frontline providers of care. Because the outcomes are collected as part of routine practice, nurses and other clinicians have the opportunity to receive real-time feedback about patient outcomes achievement. This opportunity for real-time feedback about how patients are responding to health-care interventions provides an ideal opportunity to link real-time outcomes feedback with knowledge-translation activities.

Patient outcomes are defined as changes in the patient’s health status that can be attributed to antecedent health care (Donabedian 1980). Outcomes measurement tells us about how a patient is responding to a health-care intervention but outcomes data can also be used as a basis for planning and evaluating health-care delivery. The value of outcomes research and its relevance to EBP is illustrated in the following two studies (Bernabei et al. 1998; Zyczkowska et al. 2007). Bernabei et al. followed approximately 13,000 cancer patients discharged to home from hospital and found that approximately 4000 (~29%) reported pain on a daily basis (Bernabei et al. 1998). Twenty six percent of the patients who experienced pain on a daily basis received no analgesia at all, contrary to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) best-practice guideline recommendations for cancer pain management (Zech et al. 1995). A decade later we still observed problems with effective pain management. Zyczkowska et al. followed the outcomes of 193,198 home care and complex continuing care clients and found there was a consistent decline in the percentage of patients receiving analgesia consistent with the WHO best-practice recommendations among those in the highest age groups (Zyczkowska et al. 2007). Centenarians (those 100 years of age or older) made up 0.41% (n = 788) of the sample. Twenty percent of the clients aged 100 years and older were receiving no analgesia agents for their pain. These studies clearly demonstrate a disconnect between the knowledge, the outcomes, and the care provided. This chapter will explore how outcomes-focused knowledge-translation can be utilized to change this picture by improving EBP.

The premise underlying outcomes-focused knowledge translation is that health-care professionals will be motivated to change their practice through access to real-time feedback about their patients’ outcomes and through timely access to best-practice guidelines and other forms of evidence that inform decision making. EBP is the process of shared decision making between practitioner, patient, and others significant to them based on research evidence, the patient’s experiences and preferences, clinical expertise or know-how, and other available robust sources of information (Sigma Theta Tau International 2005–2007 Research and Scholarship Advisory Committee 2008: p. 57). One mechanism by which outcomes feedback is expected to improve evidence-informed decision making and treatment outcomes involves critical reflection about what is working and what is not working in patient care. A second mechanism by which outcomes feedback is expected to improve treatment outcomes may involve improved communication between the clinician and patient (Pyne & Labbate 2008). Research by Lambert suggests that patient-focused outcomes-feedback endeavors to improve outcomes by monitoring patient progress and providing this information to clinicians in order to guide ongoing treatment (Lambert et al. 2005).

Practice reflection based on outcomes

If a patient’s outcomes are not responding in the desired direction or at the expected rate of change, the outcomes feedback should encourage clinicians to reflect on their practice. With regard to such reflection, a central finding from cognitive psychology is that human reasoning can be characterized as involving two parallel forms of processing. The first form, a fast, intuitive, relatively automatic form of reasoning, can stem either from instinctual cognitive processes or from highly practiced, over-learned behavior (Brehaut et al. 2007). The second form is a slower, rational, deliberative form of reasoning. Brehaut et al. (2007) noted that knowledge structures that allow for fast, intuitive reasoning are a central component in the development of medical expertise. For novices, every decision must involve deliberative consideration of relevant signs and symptoms, while for experts many decisions can be made effortlessly (Brehaut et al. 2007). However, they further note that for all its advantages, intuitive reasoning is also subject to a well-known range of biases and contextual errors. The goal of outcomes-focused knowledge translation is to stimulate rational deliberative reasoning about the patient’s response to health-care intervention and about the most appropriate patient-care interventions. Those interventions are ones that are based on the best available evidence and on patient preferences. Therefore, the aim of outcomes-focused knowledge translation is to shift practice away from unproven interventions toward EBPs.

Lockyer et al. (2004) suggested that reflection is the “engine” that shifts surface learning to deep learning and transforms knowing in action into knowledge in action. They noted that reflection changes current knowledge, experiences, and feelings into new knowledge. Practice reflection enables the clinician to gain an understanding of what is effective in a particular patient context. Evidence in combination with reflection helps the clinician to attain an understanding of the change in practice that is required.

Outcomes feedback

The literature on cognitive psychology clearly indicates that improving performance in any complex task is dependent on feedback, in particular, feedback that is immediate and specific (Brehaut et al. 2007; Jamtvedt et al. 2003). Audit and feedback approaches involve measuring provider performance over many patients and then providing generalized feedback about how that performance stands within a distribution of other provider colleagues (Foy & Eccles 2009). This ordinarily occurs well after individual patient-care decisions have been made. However, effective performance improvement requires more immediate and specific feedback (Brehaut et al. 2007; Kluger & DeNisi 1996). Outcomes feedback provides health professionals with specific information related to the results of their work, information that is essential for improving performance (Kluger & DeNisi 1996). Care provided in the absence of knowledge of its impact, even if based on the best available evidence, can be misdirected. Furthermore, practice guidelines established for specific diagnostic groups still need to be tailored to the needs of the individual patient and adapted based on the patient’s response to treatment as evidenced by the patient’s outcome status (DiCenso 1999).

The effects of Feedback Intervention (FI) on performance are well documented (Axt-Adams et al. 1993; Gill et al. 1999; Heffner 2001; Thompson O’Brien et al. 2002); however, the evidence demonstrates considerable variation in impact (Doran & Sidani 2007; Kiefe et al. (2001). Kiefe et al. (2001) have shown that providing feedback in comparison to results achieved by the best performing providers can be more effective than providing feedback comparing individuals to average results. Doran and Sidani (2007) found that FIs have primarily targeted feedback about the processes of care/healthcare intervention. Outcomes feedback is identified as an important element in performance improvement that is often used in chronic disease management to provide clinicians with information about treatment outcomes (Pyne & Labbate 2008; Von Korff et al. 1997). In another care context, Slade et al. (2006) found that mental health standardized outcomes assessment, consisting of quality of life, mental health problem severity, and therapeutic alliance, along with feedback to clinicians and patients every 3 months was associated with fewer psychiatric admissions. A meta-analysis of clinical trials by Lambert and colleagues (2005), utilizing 2,500 cases, found significant improvement in psychotherapy treatment outcomes following outcomes-feedback interventions. The outcomes feedback not only reduced patient deterioration but also led to improvement in clinically meaningful outcomes (Lambert et al. 2005). Lambert et al. (2005) concluded that therapists became more attentive to a patient when they received feedback that the patient was not progressing as expected. Pyne and Labbate (2008) designed a study to determine which outcome domains were preferred by patients with schizophrenia to be included in a real-time FI. Overall, physical health problems were the most preferred outcome domain, followed by medication side effects, and satisfaction with mental health treatment. The long-term goal of Pyne and Labatte’s research is to include the patient perspective in the design of real-time outcomes FI (Pyne & Labbate 2008). Through each of these studies the patient’s perspective is confirmed as an important component of evidence-informed decision making.

The objective in outcomes-focused knowledge translation is to provide the feedback to clinicians at the point-of-care. Point-of-care in this context is where clinicians and patients interact and could include the bedside, an ambulatory clinic, the home, or even an electronic communication. A computerized handheld “information gathering and dissemination system” (e-Volution in Outcomes-Focused Knowledge TranslationTM) was developed that enables nurses, simultaneously to: (a) assess and record patient outcomes information through a wireless network using personal digital assistants (PDAs) or mobile tablet personal computers (PCs); (b) present information in summary format for case-based reasoning; (c) experience real-time feedback of patient outcomes information; and (d) reference practice information, such as best-practice guidelines, at the point-of-care (Doran & Dipietro 2008; Doran et al. 2007a). In this system, feedback is provided in two formats: (i) clinicians receive feedback about change in the patient’s outcomes in graphical format and (ii) clinicians have the ability to benchmark their patient’s outcomes relative to similar patients. The similarity is based on medical diagnosis, co-morbidities, age, and gender. This feedback serves as a decision aid, prompting the nurse to re-evaluate the plan of care if the patient’s outcomes are not improving or not changing at either the expected rate or in the expected direction. The system was evaluated in a study that engaged six settings: three hospitals and three home-care agencies. Acute care nurses in the study who used PDAs to assess patient outcomes, receive real-time feedback, and access best-practice guidelines reported that communication improved significantly. They also found that, with respect to feedback, they were more likely to receive information in a timely manner when their patient’s condition changed (Doran et al. 2007b).

Patient preferences for care

Evidence-based medicine is “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current, best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (Sackett et al. 1997: p. 2). In nursing, evidence base has come to mean more than just the use of research in practice (Ciliska et al. 2001). Engaging the patient in the evidence gathering is recognized as a significant component of EBP (Coyler & Kamath 1999; Sidani et al. 2006). Coyler and Kamath (1999) proposed an approach to care that integrates the evidence base with a patient-centered focus. That integrated approach consists of identifying effective interventions, presenting the pros and cons of different treatment options to the patient, and incorporating the patient’s preference in the treatment recommendation. Sidani et al. (2006) describe another patient-centered evidence-based approach to care involving three steps: identifying alternative treatment options that are found effective and relevant, on the basis of the best available evidence; consulting with patients to elicit their preference for alternative treatment options; and accounting for patients’ preference in providing treatment. Treatment preference reflects the person’s expression of values and attitude toward alternative interventions. In Spring’s research (Spring 2007) “preferences are the lynchpin in the movement towards shared health decision-making” (p. 614). Shared decision making is defined as “a decision making process jointly shared by patients and their health care providers” (Legare et al. 2008: p. 526). A systematic review of the barriers and facilitators related to shared decision making found that the three most frequent barriers were time pressure, lack of applicability due to patient characteristics, and lack of applicability due to the clinical situation (Legare et al. 2008). The three most often identified facilitators were: (1) motivation of health professionals, (2) the perception that shared decision making will lead to a positive impact on patient outcomes, and (3) the perception that shared decision making will lead to a positive impact on the clinical process (Legare et al. 2008).

In outcomes-focused knowledge translation, clinicians engage patients systematically in treatment decision making by eliciting their preferences for care, clarifying their values, and incorporating the evidence into clinical decision making about health-care intervention. Of interest in this regard, an electronic clinical decision support system has been developed that provides clinicians with timely access to clinical evidence and feedback data about patient outcomes at the point-of-care. The system is designed to address many of the barriers to shared decision making identified by Legare et al. (2008). For example, timely access to evidence at the point-of-care addresses some of the time barriers clinicians experience because the evidence is available at the time of clinician–patient discussion. The outcomes-feedback data are important to enabling clinicians to see the positive impact of shared decision making on patient outcomes. Clinical expertise is needed to integrate the evidence from research and from patient preferences and values, and to determine the intervention/treatment that is most appropriate for the patient (Doran & Dipietro 2008; Doran et al. 2009). Patient involvement in care or treatment-related decision making has been associated with increased sense of control, increased satisfaction with care, and improved functional and clinical outcomes (McCormack et al. 1999; Street & Voigt 1997). In a study of the extent to which patients and care providers desire mutual decision making, BeLue et al. (2004) found that patient involvement in decision making is largely dependent upon the provider. “Patients look to providers to assist them in decision making and expect providers to tell them not only the full scope of treatment options but also how they can engage in clinical decision making” (Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overbolt 2006: p. 125). The development of tools to measure patient preferences is a burgeoning area in medical research (Spring 2007) and should be incorporated into electronic decision support tools for use at the point-of-care.

Facilitation to support change

Facilitation is the technique by which one person helps others to understand what they have to change and how they change it to achieve the desired outcome (Kitson et al. 1998). The facilitator role is an important component of the PARIHS model (Kitson et al. 1998; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2002). Harvey et al. (2002) noted the kinds of strategies thought to be effective in facilitating EBP. These include change management techniques such as academic detailing, educational outreach visits, audit and feedback (described earlier), social influence, and marketing approaches. They further observed that the most effective implementation strategies are those that adopt a multifaceted approach (Harvey et al. 2002). In a study of information behavior in the context of improving patient safety, McIntosh-Murray and Choo (2005) found advanced practice nurses performed an important role as “information/change agent” for inpatient nursing teams. The functions of the information/change agent included: (a) acting as a boundary spanner between the frontline staff nurses’ patient level of focus and the system-process level and between staff nurses and resources outside the unit; (b) acting as an information seeker for frontline staff nurses and seeking appropriate information; and (c) acting as a change champion with “just-in-time” education, change initiatives, and ongoing coaching. In the Advancing Research and Clinical Practice through close Collaboration (ARCC) model the facilitator is referred to as an EBP mentor (Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overbolt 2006). Mazurek Melnyk and Fineout-Overbolt (2006) describe the elements of the EBP mentor role as providing knowledge and skills about research to others, assisting others to hone their skills in assessing patient preferences, and incorporating patient preferences into clinical decision making.

In outcomes-focused knowledge translation, facilitation involves each of the characteristics described earlier. It also draws on techniques and approaches from quality-improvement literature and from learning theory. From that literature we know that the facilitator needs to assist staff in interpreting significant trends in outcome achievement by utilizing the theory of statistical process control (Berwick 1991; Deming 1986). Facilitation should include the broad participation of clinicians, managers, and other staff involved in delivering care, in measurement and statistical analysis, in problem solving through inductive reasoning, and in progress through small-scale implementation and evaluation (Herman et al. 2006). Facilitation must engage all participants in the cognitive aspects of care. “Cognitive learning often involves seeing a problem from a new perspective or viewpoint. Change requires cognitive re-organization and perhaps even the abandonment of previously learned principles or approaches” (Handfield-Jones et al. 2002: p. 951).

Self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci 2000) is a well-established and validated theory of adult motivation that pertains to the role of facilitation in achieving change. It has direct implications for adult learning through the insights it provides into how motivation relates to three of the basic psychological needs of individuals: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. It posits that humans search out growth opportunities and naturally seek to engage in meaningful activities, to enhance capabilities, and to encounter social connectedness in groups. SDT explicitly addresses the social environment of the individual striving to realize the goals of growth, improvement, and self-actualization. The social environment must support and nourish human growth-oriented endeavors. The facilitator role is an important component of the social environment because facilitators need to create a favorable learning environment where clinicians experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness in order to achieve practice change.

Related theoretical models

Model A. Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services

Outcomes–focused knowledge translation is based in cognitive learning theory (Kluger & DeNisi 1996; Ryan & Deci 2000) and was conceptualized as an approach to operationalize the concepts from the PARIHS model (Kitson et al. 1998; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2002) at the point-of-care. The PARIHS model provides a framework for guiding the continuous improvement of nursing practice through EBP (Kitson et al. 1998; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2002). Kitson et al. (1998) suggest that successful implementation of evidence into practice is a function of the relationship between (a) the nature of the evidence, (b) the context in which practice change will occur, and (c) the mechanisms by which the change is facilitated. They describe the nature of evidence in three formats: research information, clinical experience, and patient choice. Successful implementation into practice is most likely when the research evidence is of high quality, where there is high professional consensus concerning the evidence, and where there is a process for systematic feedback and input from patients into health-care decision making. The context is the environment or setting in which the proposed change will be implemented. It consists of three elements: the prevailing culture, the leadership roles assigned, and measurement, that is the organization’s approach to monitoring its systems and services. Facilitation, as previously indicated, is the technique by which one person helps others to understand what they have to change and how they change it to achieve the desired outcome (Kitson et al. 1998).

Practice development, as conceptualized by Kitson and colleagues, involves the continuous improvement of patient care through EBP (Kitson 2002; McCormack et al. 1999). The PARIHS model is helpful in identifying the important elements within the practice setting that need to be in place in order to foster EBP change. It identifies performance measurement as an important component of the context for change. However, previous descriptions of the model do not specifi-cally identify which indicators are appropriate for evaluating nursing systems and services or how to use performance measurement and feedback to design and evaluate practice change. Outcomes-focused knowledge translation provides a framework to operationalize the performance measurement and feedback component of the PARIHS model. As such, it is complimentary to the PARIHS model. It should be applied in conjunction with the other knowledge-translation strategies identified within the PARIHS model. Indeed, evidence suggests that without such a multifaceted set of interventions and strategies, knowledge translation will be less successful (Graham et al. 2006).

In outcomes-focused knowledge translation patient outcomes feedback and research evidence are linked through an electronic decision support system that is designed to support evidence-informed decision making at the point-of-care. A theory-driven approach has been used to develop the decision-support system. Building on the suggestions in the PARIHS model, research findings are provided in the form of best-practice guidelines and are presented to clinicians in a “push” fashion, automatically, in response to their outcomes assessment data. Previous research suggests that it may be more effective to provide clinicians with research evidence in a “push” fashion that is automatically delivered in the form of alerts and reminders, than in a “pull” fashion, that relies on clinicians to search out the information (Bates et al. 2003). Consistent with the recommendations in the PARIHS model, a hyperlink is provided within the knowledge-translation system that enables clinicians to read about the quality of the evidence and its source. The inclusion of a discussion of the quality of the evidence and its source is thought to function as a social-persuasion mechanism, anticipating that clinicians are more likely to adopt evidence in practice when they believe the evidence comes from a credible source and is of high quality.

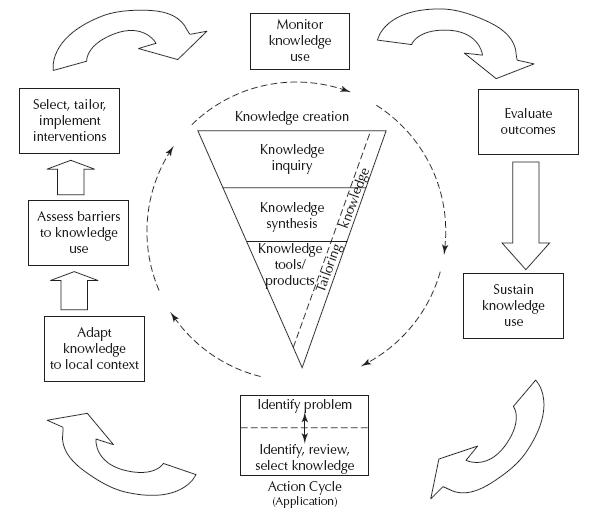

Model B. Knowledge-to-Action

Outcomes-focused knowledge translation can also fit within a broader framework for knowledge-to-action (KTA) developed by Graham et al. (2006). KTA is a process for practice change that consists of two concepts: knowledge creation and action (see Figure 4.2). Within KTA, knowledge is seen to be primarily empirically derived (i.e., research based) but also encompasses other forms of knowing such as experiential knowledge. The knowledge concept, represented by the funnel in Figure 4.2, represents knowledge creation and consists of the major types of knowledge or research, namely, primary research, knowledge synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis), and knowledge tools and products (e.g., best-practice guidelines, decision-support tools) (Graham et al. 2006). As knowledge moves through the funnel it becomes more distilled and refined. Knowledge inquiry represents the multitude of primary studies or information of variable quality. This is referred to as first-generation knowledge that is in its natural state. Knowledge synthesis, or second-generation knowledge, represents the aggregation of existing knowledge. At this stage the knowledge often takes the form of systematic reviews. Knowledge tools or products are third-generation knowledge and most often take the form of practice guidelines, decision aids, and rules.

Figure 4.2 Knowledge-to-action framework.

Reprinted, with permission, from Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., CaswellL, W. & Robinson, N. (2006) ‘Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map’. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, 13–24.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree