An Introduction to Community Activism

DeAnne K. Hilfinger Messias

“Action indeed is the sole medium of expression for ethics.”

—Jane Addams

Community activism is the means through which individuals, groups, and organizations work together to bring about specific, often radical, changes in social, economic, environmental, and cultural policies and practices. The broad goal of community activism is to enact social transformation that contributes directly to improving living conditions, enhancing community environments, and eliminating health and social disparities. Community activists engage in collaborative, sustained actions focused on changing underlying structures or removing barriers—be they political, social, economic, environmental, or cultural—with the ultimate aim of improving the lives of individuals or groups subjected to disparate, discriminatory, or oppressive conditions (Table 92-1). The primary focus on changing underlying or contributing structures, practices, or policies is what distinguishes community activism from community service, the provision of goods or services for underserved or underprivileged individuals or groups (Jennings, Parra-Medina, Messias, & McLoughlin, 2006; Jennings, Messias, & Hardee, 2010). It is further distinguished from community development, in which the primary focus is to enhance existing social and economic infrastructures through the creation of new service programs, leadership training, and innovative partnerships (Larsen, 2004). Another distinguishing characteristic of community activism is that the primary commitment and motivation for change are generated from within the community of interest. In contrast, the motivation, expertise, and resources for community service and development often originate outside the local community.

TABLE 92-1

Types and Definitions of Community Actions

| Type of Community Action | Definition |

| Community activism | Collaborative, sustained actions focused on changing structures or removing barriers with the ultimate aim of improving the lives of individuals or groups subjected to disparate, discriminatory, or oppressive social, economic, political, cultural, or environmental conditions |

| Community development | The creation of new programs and services in order to improve and enhance local social and economic infrastructures |

| Community service | The provision of goods or services for underserved or underprivileged individuals or groups |

Key Concepts

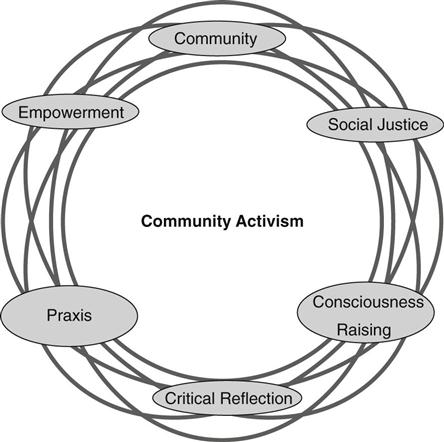

The concepts of social justice, community, consciousness-raising, critical reflection, praxis, and empowerment are integral to community activism (Figure 92-1).

Social Justice

Social justice is a philosophical, political, and public health concept rooted in the ideal of human rights and social equity (Reichert, 2007). The equitable distribution of resources and opportunities for a productive and fulfilling life is a human rights concern. Prerequisites for social justice include the establishment and assurance of equal treatment under the law, equal access opportunities, and fair and equitable distribution of resources. Yet in many communities around the globe, availability and access to basic resources and opportunities (i.e., clean air and water, adequate and nutritious food, appropriate housing, safe and secure neighborhoods, equitable educational opportunities, the means to a productive and fulfilling livelihood, affordable culturally appropriate health services, and fair and equal treatment under the law) are not equitably distributed among all individuals and groups. Rather, factors such as social privilege or market forces determine the distribution of these key resources and opportunities, resulting in social injustices and inequities. Overcoming social injustice requires collective action and solutions on multiple fronts. One of the ways the ideal of social justice is translated into practice is through community activism.

Community

Community is a dynamic and fluid concept, conceptualized and practiced in diverse ways. In relation to activism, community implies the actual involvement of individuals and groups directly impacted by the specific issues or conditions that are the focus of change. In a more traditional sense, community—or grassroots—activism is considered to be locally generated and locally focused. Many community activists are located within and focused on creating change in a specific geographic location, such as the neighborhood, school district, or city where they live, study, or work. Neighborhood activists frequently mobilize around issues related to public safety, environmental health, education, land use, zoning, and economic development. The focus may be location-specific (e.g., getting traffic signs installed at busy intersections, organizing a neighborhood watch or clean-up effort, eliminating the presence of alcohol and tobacco advertising in low-income and minority neighborhoods) or may address broader structural issues such as economic development or environmental pollution.

In the United States, education is a common focus of activism involving students, parents, teachers, and the broader community. For example, in 2002, Mayor Jerry Brown hired 100 police officers to patrol Oakland, California’s underfunded public schools serving primarily African-American and Hispanic youth. This policy decision prompted the mobilization of the very youth intended as the target of armed police surveillance. In protest of the surveillance-based policy focus, Oakland students organized youth rallies and a march on City Hall, forcing the mayor to acknowledge other approaches to youth development and to allocate $7 million to Oakland youth programs (Ginwright & Cammarota, 2006). Similarly, the implementation of bilingual education programs in southwest Chicago public schools came about in response to Mexican-American community activism (Stovall, 2006).

Grassroots activists also mobilize across geographical and social communities. Historically, community activists have participated in broader social movements (e.g., the women’s rights, civil rights, workers’ rights, and environmental health movements). Much activism occurs within the context of communities formed through affiliation with a collective social identity (e.g., a cultural or ethnic group, race, or religion) or shared sense of political responsibility. Collective social identities related to specific health issues (e.g., HIV/AIDS, cancer, mental health, tuberculosis, women’s reproductive health) have given rise to significant community activist movements. Over the past 25 years, what is now a global HIV/AIDS movement began as local activism within gay communities in the U.S., Canada, Western Europe, and Australia. These early activists mobilized to educate their own communities around HIV prevention and, at the same time, demand responsive public action from governments, medical researchers, health care providers, pharmaceutical companies, and legal systems (Piot, 2006). Subsequent HIV/AIDS grassroots mobilizations have involved diverse communities, including persons living with AIDS in Brazil, Uganda, and South Africa; sex-workers in Thailand; religious and community leaders in Senegal; and impoverished mothers of childhood AIDS victims in Romania. Through relentless advocacy and demands for changes in public policy as well as local health care systems, HIV/AIDS community activists have provoked governmental and industry responses, resulting in more effective prevention and access to treatment and significantly impacting the global HIV/AIDS epidemic (Marcolongo, 2002; Piot, 2006).

Consciousness Raising, Critical Reflection, and Praxis

Consciousness raising, critical reflection, and praxis are three interrelated components of community activism. Underlying liberatory approaches to community activism is the premise that empowerment emerges from engagement in focused dialogue, listening, critical reflection, and reflective action (Freire, 1970, 1973). One of the first steps of engaging participants in activist endeavors is to increase public awareness of specific issues and the associated root causes.

Consciousness Raising

Consciousness raising goes beyond simply presenting others with information to actually engaging with others in critical reflection. Popular educator and community activist Paulo Freire originally defined and applied the concept of conscientização (Portuguese for “conscientization”) in his community-based work with illiterate Brazilian peasants. Conscientization is a reflective process in which individuals and groups examine their own particular situations and contexts in order to identify social, economic, cultural, political, and environmental forces contributing to these situations. Critical awareness arises through the reflective processes of problem-posing and interpretive decoding of lived experiences.

Critical Reflection

Critical reflection is integral to understanding the linkages and connections between a local community’s issues and problems and those of other communities across the globe. By engaging in critical dialogue and reflection, community activists begin to envision possibilities for collective action leading to transformation (Jennings et al., 2010). Critical reflection also involves attention to the political processes and actions necessary to challenge inequalities and effect change. Praxis is purposeful, reflective action arising out of individual and collective conscientization and theorizing, grounded in a commitment to building a more just society, through diverse means, including culture circles, critical pedagogies, action research, and community activism (Freire, 1970, 1973; Hesse-Biber, 2007; Stovall, 2006). Community activism is a form of critical social praxis, an iterative cycle of conscientization-reflection-reflective action in which relations of power and inequality are identified, challenged, and changed.

Empowerment

Empowerment is a multilevel construct that incorporates processes and outcomes of social action through which individuals, families, organizations, and communities gain control and mastery within the social, economic, and political contexts of their lives in order to attain greater equity and improve the quality of life (Jennings et al., 2006). At the individual level, empowerment may result from the generation of new knowledge and understanding of issues and the development of new skills among community activists. This individual empowerment then can be linked to community organizing to support social action and political change, as well as to individual self-protective and other socially responsible behaviors (Wallerstein, Sanchez-Merki, & Velarde, 2005). Collective empowerment occurs within families, organizations, and communities. It involves processes and structures that enhance members’ skills, provide them with mutual support necessary to effect change, improve their collective well-being, and strengthen intraorganizational and interorganizational networks and linkages to improve or maintain the quality of community life.

The process of making connections between personal experiences and broader social issues is integral to personal and community empowerment and to effective action. In describing a youth empowerment program at an alternative high school for youth unable to succeed within the traditional educational system, Mitra (2008) reported an adult advisor’s observation that “The kids involved are changing [from] delinquent into activists. [They can see] how they got sucked into being delinquent and the criminal justice system through their upbringing—not just their family, but the community and the policies” (p. 210). The purpose of empowerment education is to develop the requisite knowledge and skills for community activism, particularly among youth. By participating in community action projects (e.g., peer teaching, the production of murals, cultural institutes, the creation of videos for use in educational efforts, or photo-voice projects), youth and other potential activists develop the requisite knowledge and skills for community activism as they engage in collective consciousness-raising, critical reflection, and reflective action (Messias, McLoughlin, Fore, Jennings, & Parra-Medina, 2008).

Taking Action to Effect Change: Characteristics of Community Activists and Activism

Activists not only recognize injustice but are willing to take action to correct it (Sherrod, 2006). Situated across the social, economic, and political spectrum, activists share a desire to contribute to the collective welfare and create a more just and equitable society. Motivation and commitment of personal time and energy to social involvement, a willingness to take risks, and the belief in power and efficacy of groups to effect change are common characteristics among community activists. The motivation may be rooted in personal or professional experience, empathy, or solidarity (Lewis-Charp, Yu, & Soukamneuth, 2006; Montlake, 2009). Due to the risks embedded in social justice work, activists must individually and collectively assess the potential harm that may come from actions, help each other prepare if they choose to take calculated risks, and take steps to protect themselves and others as best as possible when they do (Cohen, de la Vega, & Watson, 2001).

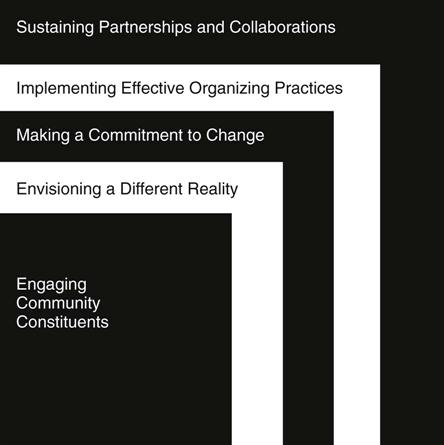

Community activism grows out of the desire to change existing social, political, or environmental conditions. In their commitment to change and transform the way power is distributed or controlled, activists draw on the power of the people and the community (power within) and exert pressure on those who hold institutional power (power over). Characteristics of successful community activism include the ability to frame issues and envision a different reality, a clear commitment to change at various levels, the implementation of effective organizing practices and actions, and the ability to develop and sustain collaborative partnerships and relationships (Figure 92-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree