Adolescent Sexual Activity and Teenage Pregnancy

Frances A. Maurer

Focus Questions

How prevalent is sexual activity among U.S. adolescents?

What are some of the factors that influence a teenager’s decision to engage in sexual activity?

What are some of the risks associated with early sexual activity?

What are some of the reasons teenagers become pregnant?

What are some of the factors associated with increased risk for pregnancy for young girls?

What are some of the social costs of teenage pregnancy?

How can community/public health nurses act to reduce the risks of teenage pregnancy?

What are the nurse’s responsibilities as a health care professional visiting an at-risk family?

What community programs are available to assist teenage parents and their children?

Key Terms

Abstinence-only programs

Comprehensive sex education programs

Life options programs

Low birth weight

Risky behaviors

Sexting

Teenage sexual activity

Unintended pregnancy

Unprotected intercourse

Virginity pledgers

Teenage sexual activity involves sexual intercourse and other sexual acts in adolescents younger than 20 years of age. Early sexual activity is very common and is accompanied by major public health concerns such as increased risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), pregnancy, and early parenthood. Adolescent parents are more likely to have substantial problems adjusting to parenthood and acquiring adequate parenting skills. Their children are often affected by their difficulties. Children born to younger teens are at greater risk for health problems than children born to mothers in other age groups (Martin et al., 2010b; Mathews and MacDorman, 2010).

Although substantial progress has been made in educating teens and in influencing sexual behaviors, much remains to be done. The teenage pregnancy rate is the lowest ever recorded, and as a result both the birth rate and the abortion rate among teenage girls have also declined (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [MMWR], 2011a). There is evidence to suggest that teens are delaying the start of sexual activity, but by age 18 to 19 years, the majority (70%) of teens have had a sexual experience (Guttmacher Institute [GI], 2011a).

Teenage sexual activity

Sexual intercourse, especially unprotected intercourse (sexual intercourse without the use of barriers or other contraceptives), carries the risk for pregnancy. The level of sexual activity among teenagers is extremely high (GI, 2011a). Peer pressure, an adolescent’s need to belong, and the sexual content of media messages make it difficult for teens to delay or abstain from sexual activity.

Extent of Sexual Activity among Teenagers

Sexual activity among adolescents continues to be a prevalent issue, although some data suggest that there has been a decline in sexual activity among certain age groups. Since 1991, the number of high school teenagers who engaged in sexual intercourse decreased from 54% to 46% (MMWR, 2011a). There is some evidence to suggest that teens are delaying the age at first intercourse; however, the rate of sexual intercourse increases with age. Approximately 13% of teens have had their first sexual encounter before the age of 15 years. By age 17 years, only 27.7% of girls and 28.8% of boys have engaged in sexual activity; by the time they reach 18 to 19 years of age, 59.7% of girls and 65.2% of boys have engaged in sexual activity (Abma et al., 2010). The Healthy People 2020 objectives (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010) have identified priorities associated with teenage sexual activity, including the following (see also the Healthy People 2020 box on page 605):

• Increasing the age at first intercourse

• Reducing the number of adolescents engaging in sexual activity

• Increasing the number of adolescents who use protective measures when engaging in sexual activity.

Mixed Emotions about First Sexual Intercourse

Abma and colleagues (2010) conducted a study on teens and their first sexual intercourse. Seven percent of girls reported that their first sexual intercourse was not voluntary. In addition, 10% of girls and 5% of boys reported that they did not want their first intercourse to happen when it did, and 47% of girls and 34% of boys had mixed feelings about the timing of their first intercourse. This suggests much ambivalence about initiation of sexual activity. Educational programs and counseling should continue to stress techniques to handle pressure from peers and potential partners related to initiation of sexual activity.

Increased Frequency of Oral Sex

The practice of oral sex is now as common as intercourse in the teen population. Approximately 25% of teens substitute oral sex for intercourse. In one survey, half of the teens did not consider oral sex to be a sexual activity. Half of all college students who pledged to remain virgins reported that they engaged in oral sex (Dailard, 2003). One-third of teens reported having oral sex with someone who was not the right partner for intercourse or someone with whom they wished to delay initiation of intercourse (Chandra et al., 2011; Dailard, 2006). Most were unaware of the risk for STDs associated with oral sex.

Comparison of Teenage Sexual Behavior among Countries

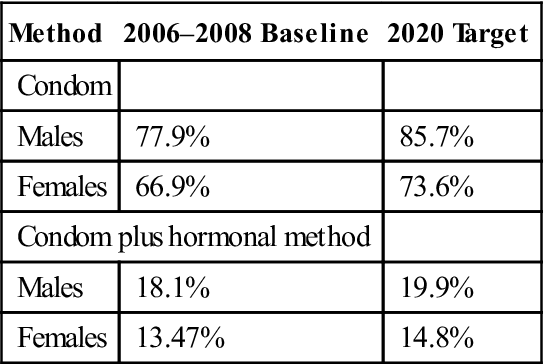

The most current comprehensive comparative study (United Nations, 2008) shows little difference in sexual experience or age at initial sexual intercourse among teenagers in developed countries (Figure 24-1). There are, however, differences in contraceptive behaviors and pregnancy rates. Teenagers in the United States are less likely to be aware of contraceptive methods, to know or to explore how to obtain and use contraceptives, and to initiate action to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancies either before or just after their first sexual experience (Abma et al., 2010; Albert, 2010). The reason for such sexually risky behavior is at least partially the way in which sexuality and sexual behaviors are addressed in the United States.

(Note: Data are for the mid-1990s.) (From Darroch J. E., Frost, J. J., Singh, S., et al. [2001]. Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries: Can more progress be made? [Occasional Report No. 3]. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute.)

In other developed countries, information about sexual intercourse and birth control is regularly provided to teenagers. Government-sponsored sex education programs in the school systems are common. Programs include health teaching on contraceptive methods, encouragement of responsible sexual activity, and easy access to contraceptives and service is generally provided in a nonjudgmental fashion (GI, 2006a). Sexuality and contraception education is mandatory in public schools in England, Wales, France, and Sweden and in most Canadian schools.

The United States provides little information on contraceptives, and contraception is not an emphasized element in most school-based sex education programs. One-third of high school students have had no formal education on contraceptives, and 24% of students received abstinence education without any information on birth control (GI, 2011b; Martinez et al., 2010). The United States has also been ambivalent about providing contraceptive services to teenagers. In some instances, federal or state funding for clinics serving large numbers of young disadvantaged females has been reduced or discontinued (see Chapters 4 21 and 27). A significant number of U.S. teenagers and their families have no health insurance and find access to any kind of health care services (including contraceptive services) difficult (Gold et al., 2009; MMWR, 2011b). Some federal programs have actively attempted to restrict rather than increase access to reproductive services.

Formal sexual education programs for adolescents are closely monitored. Parental involvement and permission requirements and abstinence-only programs are two methods supported at the federal level. Federal funding for abstinence-only sex education programs increased by 157% between 1997 and 2005 (Lindberg et al., 2006a) but has since been reduced, pending results of the efficacy of such education programs.

In 2011, 37 states required parental involvement in sex education programs, and 3 states required parental consent before a child could attend a sex education program (National Conference of State Legislatures [NCSL], 2011). The type and manner of “parental involvement” varies by state. In addition, 37 states and the District of Columbia allow parents to opt out of sex education programs for their children. By contrast, the majority of states (73%) required education about STDs and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). No program that takes federal funds is allowed to provide information about the positive effects of contraceptive use.

Factors Associated with Decisions to Engage in Sexual Activity

An adolescent’s decision to initiate sexual activity appears to be influenced by multiple factors. A brief discussion of the most important findings is presented here.

Peer Pressure and Intimacy Needs

Research suggests that one of the most important influences on a teenager’s decision to begin sexual activity is the attitudes and behaviors of peers (Albert, 2010; National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy [NCPTP), 2009a). Adolescent motives for sexual behavior are linked to the desire for intimacy, social status, and pleasure (Ott et al., 2006). Teenage girls listed intimacy as the most important motive for sexual activity, whereas teenage boys listed pleasure and social status as more important. Before 1980, race, socioeconomic status, type of neighborhood and dwelling, and religion were significantly related to age at first intercourse. Although many of these factors still have an effect, they are diminishing in significance.

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Some differences are seen in the age of onset of sexual behavior among races. African Americans are sexually active at an earlier age, but white and Hispanic youths are rapidly catching up. In 2009, 72% of all black male high school students, 53% of Hispanic males and 40% of white male students engaged in sexual activity in high school. Female teenagers of all races initiate sexual intercourse later than do adolescent males, but 58% of black females and 45% of Hispanic and white females have had sexual intercourse during high school years (MMWR, 2011a).

Reasons for Delaying Sexual Activity

Religious upbringing has some impact on adolescent sexual activity, reducing the proportion of teens who are sexually active. The main reason given by teens who have not initiated sexual activity was religious or moral beliefs (Abma et al., 2010). In addition to religious concerns, adolescents listed fears of pregnancy and STDs as reasons for delaying sexual activity. More boys (30%) than girls (10%) stated that they had not found the right partner (Abma et al., 2010). Of those who abstained during their teenage years, almost all had initiated sexual activity by 24 years of age regardless of marital status. Only 12.3% of females and 14.3% of males age 20 to 24 years reported not ever engaging in sexual activity (Chandra et al., 2011).

Socioeconomic Status, Family Composition, and Risky Behaviors

Family income and academic standing also influence the adolescent’s decision making related to sexual activity. Teenagers from poor and low-income groups are moderately more likely to be sexually active, and initiate sexual activity approximately 4 to 6 months earlier compared with adolescents from higher-income families. This is especially true for adolescent females.

Students who are academically motivated, are progressing well in school, are future oriented, and have established goals generally delay sexual activity and avoid pregnancy (Abma et al., 2010; Manlove et al., 2004). Frost and colleagues (2001) reported that for girls, education seems to delay age of first intercourse. Thirty-three percent of girls who did not complete high school reported starting sexual activity before age 15. Only 17% of female high school graduates and only 9% of females with some college education initiated sexual activity before age 15. Better school performance and parental expectations positively influenced the decisions of both boys and girls to postpone sexual activity (NCPTP, 2010a).

Common opinion links single-parent families, poor parental communication on sexual matters, and school-based sex education with early sexual activity. Teens of both sexes who are from single-parent homes are more likely to be sexually active and to have a child at a young age compared with children from two-parent families (Abma et al., 2010). Recent studies indicated that the absence of a father in the household increases the risk for both boys and girls for early sexual activity and pregnancy (NCPTP, 2009b). Girls in one-parent families or blended families and those in out-of-home placements are twice as likely to be sexually active compared with girls in two-parent families (Abma et al., 2010).

Parental connection seems to delay initiation of sexual activity and reduce risky sexual behavior (Haggerty et al., 2007; Prado et al., 2007). However, over half of teens reported that they had not talked with their parents about saying no to sex or about birth control methods (Martinez et al., 2010).

Most studies found no relationship or only very weak correlations between school-based sex education and a teenager’s decision to initiate sexual activity. The most recent evidence suggests that such education encourages the delay of initiation of sexual activity and sexually active teenagers to use contraceptives (Manlove et al., 2004; MMWR, 2011a).

Teenagers who engage in other risky behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and drug use are more likely to risk engaging in sexual activity (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2009; Eaton et al., 2006; NCPTP, 2011). This is especially true of younger teens. Adolescents 14 and 15 years of age who engage in other risky health behaviors are twice as likely as their peers to be sexually active (Albert et al., 2003). For example, 25% of sexually active young teens drink or use drugs before having sex (ACOG, 2009; Eaton et al., 2006). Children and adolescents who have been sexually abused are at greater risk for continued sexual activity (Brennan et al., 2007; Santelli et al., 2006a) (see Chapter 21).

Initiation of sexual intercourse during the teenage years tends to increase the risk for multiple partners (Abma et al., 2010; Eaton et al., 2006). The younger the adolescent at the start of sexual activity, the greater is the risk for multiple partners. Women who initiated sexual experiences by age 15 reported having more sexual partners than women who started sexual activity later in their teens (Abma et al., 2010; NCPTP, 2002). Abma and colleagues (2010) found that 30% of sexually active male and female adolescents are most likely to have had two or more partners in the previous year.

Other Factors Associated with Adolescent Sexual Activity

Early sexual maturation coupled with a prolonged transition to independence compounds the adolescent’s journey toward responsible adulthood. The number of years the youth are expected to spend in preparation for work or a career is longer than at any other time in history. Along the way, adolescents encounter mixed messages about sex, sexual activity, and responsible behavior (Albert, 2010; NCPTP, 2007). A longitudinal analysis of programming on four major television networks showed a steady increase in the amount of sexual activity and behavior (Frutkin, 1999; Kunkel et al., 1996). Fewer than 30% of sexual situations involved responsible sexual activity such as waiting to have sex or attempting to reduce the risk for STDs, HIV infection, or unintended pregnancy (Kunkel et al., 1999). L’Engle and colleagues (2006) found teens exposed to sexuality in the media were more likely to engage in sexual activity. Teens reported that TV shows which deal with teenage pregnancy or health and social problems associated with sexual activity made them think more about the consequences of sexual intercourse (Albert, 2010; NCPTP, 2007).

Sexting is a new form of sexual activity and is defined as sharing suggestive images of oneself over electronic media. Sexting has become popular with teens, many of whom do not anticipate the problems and pressures they may encounter as a result of this practice. Albert (2010) reported that most teens (71%) believe sexting leads to an increase in sexual activity among teens.

Some teens have additional concerns that can affect their decision process and behavior. Poverty, family dysfunction, and poor school performance can negatively influence the development of a healthy self-esteem, hinder long-term goal setting, and reduce future expectations. All these factors are associated with an early initiation into sexual activity and an increase in pregnancy rates (Abma et al., 2010; Boonstra, 2002; Klima, 2003). One study that linked mental health and sexual activity reported that sexually active teens were three times more likely to feel depressed and at greater risk of suicide than teens who were not (Rector et al., 2003). Additional research in this area is currently underway.

Risk for Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Early onset of sexual activity increases the risk for multiple sex partners, unprotected sex, and STDs (Abma et al., 2010; USDHHS, 2000). Each year, approximately 9 million adolescents contract an STD (Guttmacher Institute, 2006b; USDHHS, 2000). Of the top 10 infectious diseases, 5 are STDs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, AIDS, syphilis, and hepatitis B. In 2008, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study reported that 26% of girls between the ages of 14 and 19 years (3.2 million girls) were infected with at least one of the most common types of STD (human papillomavirus [HPV], chlamydia, genital herpes, trichomoniasis) (CDC, 2008). This study did not include syphilis, HIV infection, or gonorrhea, and it did not include young males. Incidence rates can be expected to be higher if the excluded STDs and young males were included in the study.

The rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes, and syphilis among sexually active teens are higher than the rates in the general population. Abma and colleagues (2010) reported that 15- to 24-year-olds acquired nearly 50% of all STDs each year. Table 24-1 provides information on selected STDs actually reported to the CDC; not all STDs are reportable. In 2009, there were over 1.2 million cases of chlamydia, of which approximately 600,000 occurred among teens and young adults (MMWR, 2011c). HIV/AIDS is a growing problem in the adolescent population. Infections are often contracted in the teenage years and remain undetected until the infected persons reach their twenties or thirties (see Chapters 7 and 8). The rates of STDs are higher among racial and ethnic minority groups and adolescents living in poverty than among adolescents in other racial groups or teens living in families with higher socioeconomic levels (see Chapters 78, and 21). As the differences among racial and ethnic groups disappear, differences in STD rates will also disappear.

Table 24-1

Sexually Transmitted Diseases among Adolescents

| Disease | New Cases |

| Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection | NA |

| Trichomoniasis | NA |

| Chlamydia | 430, 255 |

| Genital herpes | NA |

| Gonorrhea | 87, 221 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection | 2036 |

| Syphilis | 1005 |

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). 2009 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance: STDs in adolescents and young adults. Retrieved August 22, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/STD/Stats09/adol.htm; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Basic statistics. Retrieved August 22, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm.

The rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea are higher among females than among males. Much of that difference might be due to the greater extent of screening and detection provided to females by reproductive health care services. Males, who are largely asymptomatic, do not generally seek reproductive health care services, and the infections are more likely to remain undetected (ACOG, 2009; Abma et al., 2004; Chesson et al., 2004;). Females are also more likely to experience health complications from STDs, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical cancer, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy (Mayo Clinic, 2011; USDHHS, 2007).

Contraceptive Use

Contraceptive use among teenagers has steadily increased since the 1980s. Approximately 12% of teens do not use protection during intercourse (Abma et al., 2010; MMWR, 2011a). Birth control use generally starts after sexual activity has already begun. Teenagers use birth control sporadically and tend to switch methods without taking the proper precautions (Abma et al., 2010; Santelli et al., 2006b).

Condoms are the most common type of contraception used at first intercourse. More than 95% of sexually active teens reported using condoms (Abma et al., 2010). Teens who engage in sexual activity on an ongoing basis switch to more effective methods such as birth control pills, injectable Depo-Provera, and intrauterine devices. About 52% of adolescent females reported using birth control pills. Concern about HIV and STDs have led to an increased use of barrier methods (condoms) in conjunction with other birth control measures. Although dual contraceptive use in teens has increased, only 35% of teens report using two methods of birth control (Abma et al., 2010).

Poverty is associated with less access to and less successful use of reversible contraceptive measures. Poor people have difficulty obtaining contraceptive health care services and paying for birth control products. Frost and colleagues (2001) reported that poor teens are less likely to use birth control pills than those who are more economically advantaged. The price of one cycle of pills averages $30 per month. Teens who are not well off must rely on public programs to obtain contraceptive services. Public program services are financed by federal and state monies, primarily Medicaid and Title X monies. Approximately 30% (5 million) of women serviced at public-funded centers were younger than 20 years (GI, 2010a). The importance of subsidized family planning services has been stressed, but these services are likely to see additional funding cuts as both the federal and state governments deal with the current economic recession.

Teenage pregnancy

The United States has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in the developed world.

• Approximately 410,000 teenagers become pregnant each year.

• Eighty-two percent of these pregnancies are unintended.

• Of pregnancies in 15- to 17-year-olds:

• More than 400,000 babies are born to mothers younger than 19 years of age each year.

• Pregnant teenagers are more likely to drop out of high school, live in poverty, and have limited occupational choices compared with girls who do not become pregnant during the teenage years (GI, 2010b; MMWR, 2011a; Ventura et al., 2011).

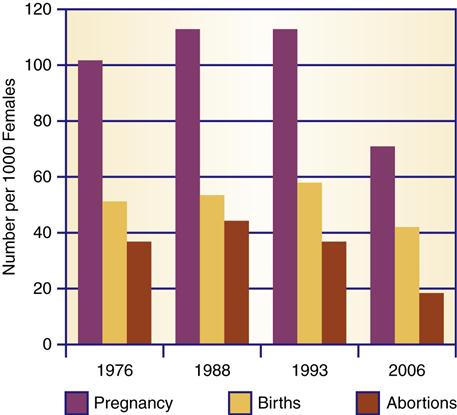

Trends in Pregnancy and Birth Rates among Teens

Preliminary figures through 2009 point to a sharp decline in pregnancy and a more moderate decline in birth and abortion rates among adolescents. Tabulation and publication of national data comparisons of pregnancy, birth rates, and abortion rates among teens are delayed by 4 or more years. Figure 24-2 shows the most current information for all three categories. In 1991, the birth rate for teens (15 to 19 years) was 62.1 per 1000. In 2009, the birth rate was 39.1 per 1000 (MMWR, 2011a). Nevertheless, both the pregnancy rate and teen birth rate remain high.

Rates per 1000 females. (Data from Guttmacher Institute. [2010]. U.S. teenage pregnancies, births, and abortion: National and state trends and trends by race and ethnicity. New York: Author; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2003]. Revised pregnancy rates, 1990-1997 and new rates for 1998-99: United States. National Vital Statistics Reports, 52[7]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; and CDC. [1999]. Highlights of trends in pregnancies and pregnancy rates by outcome: Estimates for the United States, 1976-1996. National Vital Statistics Reports, 47[29]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.)

Approximately 14% of the decline in pregnancy rates is attributable to delaying sexual activity, and 86% is related to the use of highly effective contraceptive methods among sexually active adolescent girls (Santelli et al., 2007).

Intended versus Unintended Pregnancy

Most teen pregnancies (82%) are unintended (Ventura et al., 2011). Whether intended or unintended, adolescent girls who become pregnant and choose to continue the pregnancy are more likely to come from low socioeconomic circumstances, live on their own or with one parent, have lower educational and career aspirations, and have older sexual partners (Abma et al., 2010; MMWR, 2011a).

An unintended pregnancy is an unplanned or accidental pregnancy and is accompanied by increased risks for the pregnancy, the mother, and the baby. Unintended pregnancies are more likely to result in premature or low-birth-weight babies, little or no prenatal care, abortion and miscarriages, and pregnancy complications (MMWR, 2011a; Ventura et al., 2011). Unintended pregnancies have a social cost to young mothers. These young women are at great risk for limited educational and employment opportunities, the consequences of which can last a lifetime.

Pregnancy Outcomes

Approximately 60% of pregnancies result in birth, and one-fourth of pregnancies end in abortion (see Figure 24-2). Most single mothers keep their infants rather than place them for adoption. Therefore, there is a greater demand for adoptions than there are infants placed for adoption.

Characteristics Associated with Risk for Pregnancy

Some variations are seen in pregnancy and birth rates among adolescents. A teen’s age and the age of her sexual partner, marital status, racial/ethnic group, and socioeconomic status influence the chances of pregnancy and childbirth.

Older teens have a higher pregnancy and birth rate compared with younger teens, perhaps because more of the older adolescents engage in sexual intercourse compared with younger teens. The pregnancy rate for females 15 to 17 years of age is 41.4 per 1000, and for females 18 to 19 years of age, it is 118.6 per 1000 (MMWR, 2009). The older the teen’s sexual partner, the more likely it is that an adolescent female will become pregnant.

In general, teens do not delay sexual activity or pregnancy until marriage. Marriage because of pregnancy used to be common in the past; today, few teenagers opt for marriage if they become pregnant. Approximately 84% of pregnant adolescents remain unwed (CDC, 2009). Pregnancy is, however, still the main reason for teenage marriages.

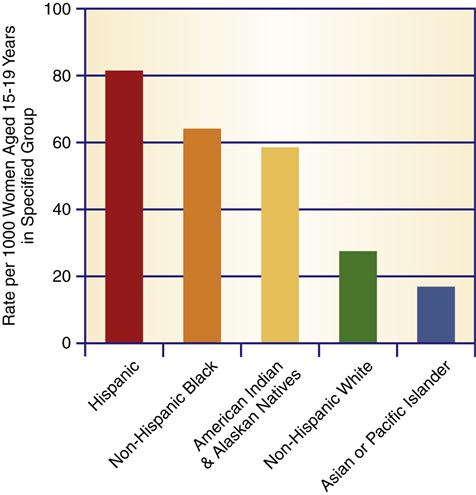

There are differences in pregnancy and abortion rates among racial and ethnic groups. The highest rates of birth are among black and Hispanic adolescents, and the lowest are among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents (Figure 24-3). The pregnancy rates in all racial and ethnic groups have declined in the past decade, with the sharpest decline in African American pregnancy rates. Abortion rates are lowest among white adolescents, perhaps because they have a lower pregnancy rate. African American adolescents chose abortion at twice the rate of Hispanic American teens. The pregnancy rates for other ethnic groups have not been as widely published. Birth rate data provide some indication of pregnancy rates. American Indian and Alaska Native teens have the third highest birth rate, non-Hispanic whites the fourth highest, and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have the lowest birth rate.

A common public perception is that among teenagers, most pregnancies and births occur in those from racial minority groups. This is not true. In 2007, white teenagers accounted for the largest percentage of births (56%), followed by black (34%) and Hispanic (4%) teens (Martin et al., 2010a). Hispanic and black teenagers have a higher proportional rate of adolescent pregnancy, but because they are fewer in number, the largest number of teenage births occurs among white teenagers.

Among adolescent females, there is a link between pregnancy rate and socioeconomic status. Teens from lower-income families start sexual intercourse at an earlier age, which increases their risk for pregnancy. Teens from lower-income groups are more likely than those from middle-income or upper-income groups to become pregnant and, once pregnant, to choose to have the baby (Abma et al., 2010; Young et al., 2004). Of teens aged 15 to 19 years, 19% of those with family income at or below 150% of the poverty level have a child, compared with 2% of teens with family incomes at or above 300% of the poverty level (Frost et al., 2001).

Reasons for Adolescent Pregnancies

With advances in birth control, increased sexual activity does not necessarily mean an increased risk for pregnancy. Why, then, are teenage pregnancy rates so high? There is no single, clear-cut answer. Teenage pregnancies occur due to a variety of reasons. Any effort to reduce the rate of adolescent pregnancies must begin with a clear understanding of the conscious or unconscious reasons and motives behind teenage pregnancies. Knowledge about the motives and reasoning of sexually active teenagers helps the community health nurse identify teens at particular risk for pregnancy. Some of the factors associated with pregnancies in the teenage population are enumerated in Box 24-1. Many teens who become pregnant do not do well academically and have few expectations for the future (Albert, 2010; Manlove et al., 2004). A study of pregnant teens in California found that 44% had dropped out of school prior to pregnancy and that many lived in chaotic family situations. Approximately 25% could not identify any future life goals. Many of the girls reported that in their social circles early childbearing was common, and almost 70% identified an adolescent friend or sibling who was either pregnant or already had a child (Frost & Oslake, 1999; Raneri & Wiemann, 2007).

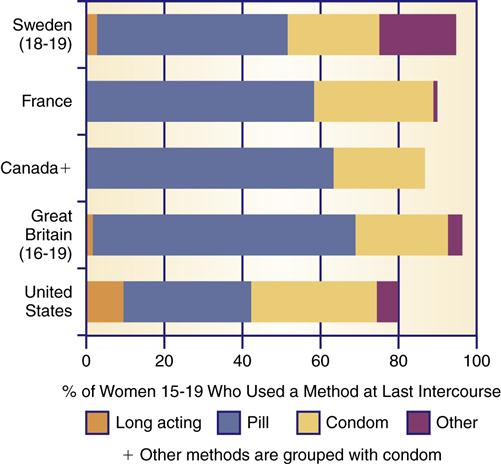

Comparison of pregnancy-related issues in other countries

Sexual activity among teenagers is commonplace in all developed countries (GI, 2001, 2006b). Although the levels of teenage sexual activity are similar, developed countries differ in the ways they deal with sex education and sexually active teens. Experts suggest that the methods used in the United States are not as effective as those used in other developed countries, as evidenced by significantly higher rates of teenage pregnancy, birth, and abortion in the United States (Abma et al., 2010; GI, 2006b).

Pregnancy Rates in Selected Countries

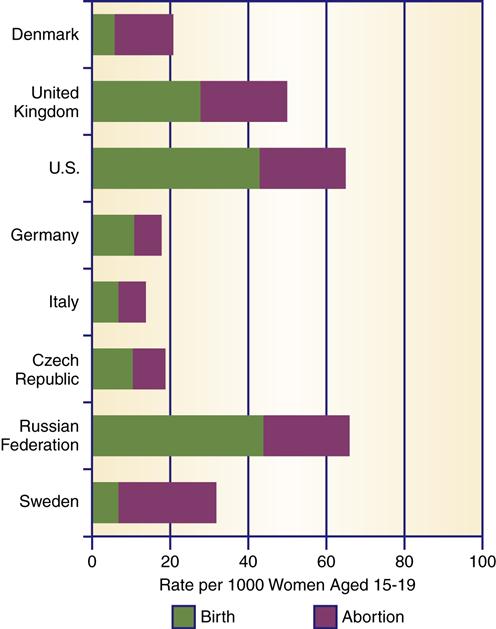

The United States leads most developed nations in the rate of teenage pregnancy (Albert, 2010; GI, 2006b). A comparison of eight countries indicates that the U.S. pregnancy rate is two or more times higher than the rates in all other comparable countries, except the Russian Federation (Figure 24-4).

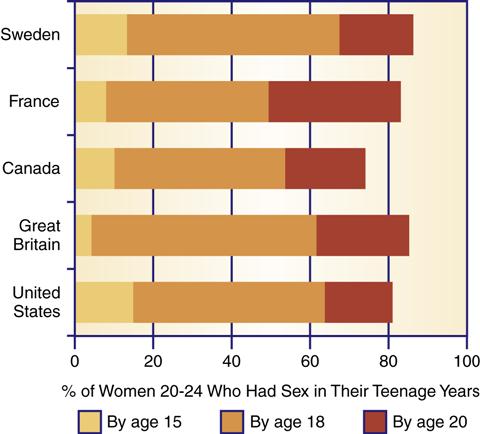

Teenagers appear to run a greater risk for pregnancy at an earlier age in the United States than in other countries (Santelli et al., 2008). A comparison of the five industrialized countries shows that in all of them, contraceptive services are more readily available and in greater use than in the United States (Figure 24-5). This disparity in availability and use can be explained partly by the different types of health insurance available in each country. The four other countries—France, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Canada—all have national health care systems. In those countries, contraceptive services and supplies are provided free or at reduced cost; contraceptives are advertised in the media; and contraceptive methods are included in the sex education programs provided to adolescents (GI, 2006b; Santelli et al., 2008). In the United States, many teens and their families lack health insurance coverage (see Chapters 4 and 21). Furthermore, birth control supplies are not advertised in print or television media, and many sex education programs restrict information to abstinence-only approaches (NCSL, 2011).

(Note: Data are for the mid-1990s.) (From Darroch J. E., Frost, J. J., Singh, S., et al. [2001]. Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries: Can more progress be made? [Occasional Report No. 3]. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute.)

Abortion Rates in Selected Countries

When teenagers become pregnant, many choose abortion, with some variations seen among countries. As with pregnancy rates, the abortion rate is higher in the United States than in four of the comparable countries (see Figure 24-4). The abortion rate in the Russian Federation is partly the result of poor access to contraceptives due to cost. The abortion rate is very similar in the United States, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In Sweden and Denmark, the rate of abortion (as a chosen alternative) among pregnant teenagers is higher than that among pregnant teenagers in the United States.

In all the comparison countries, access to abortion is less problematic, and there is little or no controversy about abortion compared with the United States. Abortion is provided by government health services or funded by national health insurance. In the United States, abortion might be covered under health insurance for those whose families have insurance, but some policies specifically deny coverage—for example, federal insurance programs and some state Medicaid programs (GI, 2006b, 2011c). Abortion services are provided by separate providers, not the teen’s or family’s regular physician or health care practice. Some states have made it more difficult for teens to have abortions, requiring parental consent, judicial reviews, waiting periods, and mandatory counseling sessions (see Chapter 6). Advocacy groups are attempting to further restrict service availability through boycotting or protest campaigns and are attempting to secure the passage of state regulations or legislation that restricts clinic operations. These efforts have met with some success.

Public costs of adolescent pregnancy and childbearing

Teenage pregnancy has both short- and long-term effects on the national economy. Public funds pay for a significant amount of the care and consequences associated with teenage pregnancy, and therefore, all taxpayers ultimately contribute to the costs associated with teenage pregnancy.

It is difficult to determine the exact health costs of teenage pregnancy and adolescent motherhood, but an estimate is $9 billion per year (MMWR, 2011a). The costs include medical care for pregnant adolescents without private health insurance and the higher costs of medical care for their infants, who are at greater risk for medical complications and death.

Young mothers and their families impact social welfare programs in ways other than medical costs. The need of young mothers to care for infants and children and their relatively low educational levels limit their ability to obtain and hold jobs that provide a living wage. As a result, adolescent mothers and their dependent children are at greater risk for needing welfare programs and for remaining in these programs for longer periods than are other welfare applicants. Between 25% to 50% of all teenage mothers receive welfare assistance after the birth of their child (Dye, 2008; NCPTP, 2010c). An estimated $23.6 billion in services was provided in 2004 to families headed by females who were teens when they had their first child (Hoffman, 2006). That amount includes funds for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF); food stamps; Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program; social service block grants; foster care; and adoption services (see the Ethics in Practice box).

Starting in 1997, limitations were placed on the amount of time young mothers could receive public assistance and subsidized health benefits. The full impact of recent reforms in the welfare system at both the federal and state levels is not yet known. All able-bodied adults receiving TANF are expected to look for work. Persons are limited to 2 consecutive years of TANF benefits and a life-time maximum of 5 years. All states make some exemption for mothers with very young babies or children, but each state’s definition of “very young” is different. For example, Oregon applies the term “very young” to children younger than 3 months of age, Texas to children younger than 4 years of age.

Because of the time limits, the impact of the 1997 changes is just now starting to become apparent. What is known is that families are moving off “welfare” programs. The preliminary data indicate that while some families have improved their economic situations, many of these families have not made a successful entry to new jobs and financial independence (Congressional Budget Office, 2007; Government Accounting Office [GAO], 2010a) (see Chapters 4 and 21). The National Center on Family Homelessness (NCFH, 2009) reported that the number of families using homeless services has increased. Some families are homeless and receiving TANF benefits. However, many more no longer qualify for TANF and are less well off. These families are without health insurance and are either chronically underemployed or working minimum-wage jobs. Changes in the TANF and in medical relief programs such as Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), as well as the effects of economic retrenchment, have long-term impacts on social program recipients (NCFH, 2009; see Chapter 21). Most states have announced cutbacks to Medicaid and state CHIP medical assistance programs and the effects of the federal budget crisis are yet to be felt.

Forcing mothers off TANF support and limiting or denying medical assistance might simply delay problems and increase public costs. When people do not have health insurance, they delay seeking care. Consequently, when they do seek medical care, their health problems are more serious, take longer to treat, and cost more to treat (see Chapter 21). The health status and quality of life of both mothers and infants who are affected by these program changes are important factors that demand serious monitoring in the next few years.

Consequences of early pregnancy for teenagers and infants

To provide quality care for pregnant adolescents, the community health nurse must understand the scope of the problem and the needs, concerns, and health issues of pregnant teenagers. There are economic, medical, and emotional consequences of pregnancy and childbearing for young mothers and their children (Albert, 2010; NCPTP, 2010b). Teenage mothers and their infants are at greater risk for serious medical complications, low birth weight of infants, and poorer outcomes compared with older women and their infants (Martin et al., 2006; NCPTP, 2010b). Teenagers who become pregnant jeopardize their educational progress and endanger their future expectations (Hoffman, 2006; NCPTP, 2010a). Children born to adolescent mothers are at greater risk for poverty. Family members and significant others are also affected because they are called on to provide physical, emotional, and financial support while burdened with their own responsibilities. Almost 8 million children live in grandparent-headed households, and 1.9 million of these children do not have a parent present in the home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Role in the Poverty Cycle

Families headed by young females have a greater chance of being poor compared with other families (Hoffman, 2006; NCPTP, 2010b). The child of a teenage mother who did not get a high school diploma or GED has a nine times greater risk of growing up in poverty compared with a child whose mother delayed having children until she was older (NCPTP, 2010c). More than 30% of single women with children live in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Poverty is accompanied by many quality-of-life problems for teenage mothers and their children, including an increase in health problems and limited access to health care services (see Chapter 21). Teenage pregnancy is viewed as the hub of the poverty cycle in the United States because teenage mothers are likely to rear children who repeat the cycle (Abma et al., 2010; Elfenbein & Felice, 2003; Hoffman, 2006).

Educational and Economic Consequences

Pregnancy affects educational achievement. Only 66% of women who become mothers in adolescence complete high school compared with 94% of women who delay childbirth until age 20 to 21 (Perper et al., 2010). Many teenagers who became pregnant were not doing well in school and had dropped out even before they became pregnant. Shearer and colleagues (2002) compared adolescent females’ test scores and found that teens with lower cognitive scores initiate sex earlier and have a higher rate of pregnancy compared with girls with higher test scores. Others drop out of school because of the demands of pregnancy and child rearing. The younger the teenager at the time of pregnancy, the greater is the danger that she will not complete high school. Teen mothers are also less likely to attend college. Only 2% of women who become pregnant before 18 years of age go on to college (Hoffman, 2006).

It is important for the community health nurse and others involved with pregnant teens to encourage the girls to remain in school, if possible. Lack of education hampers the mother’s prospects in the job market. The income of young mothers is only half that of women who delay childbearing until after 25 years of age.

Less Prenatal Care

A third of pregnant teens receive inadequate prenatal care (Chen et al., 2007). Many pregnant teenagers delay seeking prenatal care or do not receive regular care. Although the number of young women who receive first-trimester care has increased over the past 10 years, more than 33% have had no prenatal care at the end of their first trimester (NCPTP, 2010b; Philliber et al., 2003). The same teenagers at greatest risk for pregnancy—those from poor families—are also at greatest risk for poor prenatal care. In general, this group tends to be more oriented to treatment rather than prevention of illness in its health practices (see Chapter 4). Delays in seeking prenatal care might also be influenced by denial of the pregnancy and an orientation toward concrete, present-centered reasoning.