The Family After Birth

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Describe how to individualize postpartum and newborn nursing care for different patients.

4. Describe postpartum changes in maternal systems and the nursing care associated with those changes.

5. Modify nursing assessments and interventions for the woman who has a cesarean birth.

6. Explain the emotional needs of postpartum women and their families.

7. Recognize the needs of a grieving parent.

8. Identify signs and symptoms that may indicate a complication in the postpartum mother or newborn.

9. Describe the nursing care of the normal newborn.

10. Describe nursing interventions to promote optimal infant nutrition.

11. Discuss the influences related to the choice of breastfeeding or bottle feeding the newborn.

12. Explain the physiological characteristics of lactation.

13. Compare various maternal and newborn positions used during breastfeeding.

14. Identify principles of breast pumping and milk storage.

15. Illustrate techniques of formula feeding.

16. Compare the nutrients of human milk with those of infant formulas.

17. Discuss the dietary needs of the lactating mother.

18. Discuss the principles of weaning the infant from the breast.

19. Plan appropriate discharge teaching for the postpartum woman and her newborn.

Key Terms

afterpains (p. 201)

attachment (p. 219)

bonding (p. 219)

colostrum (kŏ-LŎS-trŭm, p. 223)

diastasis recti (dī-ĂS-tă-sĭs RĔK-tī, p. 208)

episiotomy (p. 204)

foremilk (p. 223)

fundus (p. 200)

galactagogues (gă-LĂK-tō-gŏgz, p. 223)

hindmilk (p. 223)

involution (ĭn-vō-LŪ-shŭn, p. 200)

let-down reflex (p. 222)

lochia (LŌ-kē-ă, p. 201)

postpartum blues (p. 211)

puerperium (pū-ŭr-PĒ-rē-ŭm, p. 199)

rugae (p. 203)

suckling (p. 225)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

The postpartum period, or puerperium, is the 6 weeks following childbirth. This period is often referred to as the fourth trimester of pregnancy. This chapter addresses the physiological and psychological changes in the mother and her family and the initial care of the newborn.

Adapting Nursing Care for Specific Groups and Cultures

The nurse must adapt care to a person’s circumstances, such as those of the single or adolescent parent, the poor, families who have a multiple birth, and families from other cultures.

Adolescents, particularly younger ones, need help to learn parenting skills. Their peer group is very important to them, so the nurse must make every effort during both pregnancy and the postpartum period to help them to fit in with their peers. They are often passive in caring for themselves and their infants. They may also be single and poor. Poor, young adolescent mothers often have several children in a short time, which compounds their social problems.

A single woman may have problems making postpartum adaptations if she does not have a strong support system. Often she must return to work very soon because she is the sole provider for her family.

Poor families may have difficulty meeting their basic needs before a new infant arrives, and a new family member adds to their strain. Women may have inadequate or sporadic prenatal care, which increases their risk for complications that extend into the puerperium and to their child. They may need social service referrals to direct them to public assistance programs or other resources.

Families who add twins (or more) face different challenges. The infants are more likely to need intensive care because of preterm birth, which delays the parents’ attachment and assumption of newborn care. It is also difficult for the parents to see the individuality of each infant, and they may be more likely to attach to them as a set. The infants may require care at a distant hospital if their problems are severe. Financial strains mount with each added problem.

Cultural Influences on Postpartum Care

The United States has a diverse population. Special cultural practices are often most evident at significant life events such as birth and death. The nurse must adapt care to fit the health beliefs, values, and practices of that specific culture to make the birth a meaningful emotional and social event as well as a physically safe event. See Chapter 6 for specific cultural practices during labor, delivery, and postpartum.

Using Translators

The nurse may need an interpreter to understand and provide optimal care to the woman and her family. If possible, when discussing sensitive information the interpreter should not be a family member, who might interpret selectively. The interpreter should not be of a group that is in social or religious conflict with the patient and her family, an issue that might arise in many Middle Eastern cultures. It is also important to remember that an affirmative nod from the woman may be a sign of courtesy to the nurse rather than a sign of understanding or agreement. Cultural preferences influence the presence of partners, parents, siblings, and children in the labor and delivery room (Figure 9-1).

Dietary Practices

Some cultures adhere to the “hot” and “cold” theory of diet after childbirth. Temperature has nothing to do with which foods are hot and which are cold; it is the intrinsic property of the food itself that classifies it. For example, “hot” foods include eggs, chicken, and rice. Women may also prefer their drinking water hot rather than cool or cold. Other hot-cold dietary practices include a balance between yin foods (e.g., bean sprouts, broccoli, and carrots) and yang foods (e.g., broiled meat, chicken, soup, and eggs).

Postpartum Changes in the Mother

Table 9-1 summarizes nursing assessments for the postpartum woman. See Chapter 10 for additional information about postpartum complications.

Table 9-1

Summary of Nursing Assessment Postpartum*

| ASSESSMENT | INTERVENTIONS |

| Vital signs | Report temperature above 38° C (100.4° F) or abnormal heart or respiratory rates |

| Fundus | Evaluate firmness, height, and location. |

| Lochia | Observe for character, color, amount, odor, and presence of clots. |

| Perineum | Observe for hematoma, edema, and episiotomy using REEDA scale; note hemorrhoids and degree of discomfort, if any. |

| Bladder | Observe for fullness, output, burning, and pain. |

| Breasts | Check for engorgement, nipple tenderness, and breastfeeding. |

| Bowels | Determine passage of flatus, bowel sounds, and defecation. |

| Pain | Determine location, character, severity, use of relief measures, and need for analgesics. |

| Extremities | Observe for signs of thrombophlebitis, ability to ambulate, and Homans sign. |

| Emotional | Evaluate family interaction, support, and any signs of depression. |

| Attachment | Observe for interest in newborn, eye contact, touch contact, and ability to respond to infant cries. |

| Cultural variations | Observe for cultural practices that the staff can incorporate into a plan of care. |

REEDA, Redness, edema, ecchymosis, drainage, approximation.

*Routine assessments are usually done every 4-6 hours unless risk factors exist. An acronym that helps remember and organize the postpartum assessment is BUBBLE-HE Breast; Uterus; Bladder; Bowels; Lochia; Episiotomy (perineum); Homans sign; Emotions or bonding.

Reproductive System

Following the third stage of labor, there is a fall in the blood levels of placental hormones, human placental lactogen, human chorionic gonadotropin, estrogen, and progesterone that help return the body to the prepregnant state. The most dramatic changes after birth occur in the woman’s reproductive system. These changes are discussed in the following sections, and the nursing care is discussed for each area as applicable.

Uterus

Involution refers to changes that the reproductive organs, particularly the uterus, undergo after birth to return them to their prepregnancy size and condition. The uterus undergoes a rapid reduction in size and weight after birth. The uterus should return to the prepregnant size by 5 to 6 weeks after delivery. The failure of the uterus to return to the prepregnant state after 6 weeks is called subinvolution (see Chapter 10).

Uterine Lining.

The uterine lining (called the endometrium when not pregnant and the decidua during pregnancy) is shed when the placenta detaches. A basal layer of the lining remains to generate new endometrium to prepare for future pregnancies. The placental site is fully healed in 6 to 7 weeks.

Descent of the Uterine Fundus.

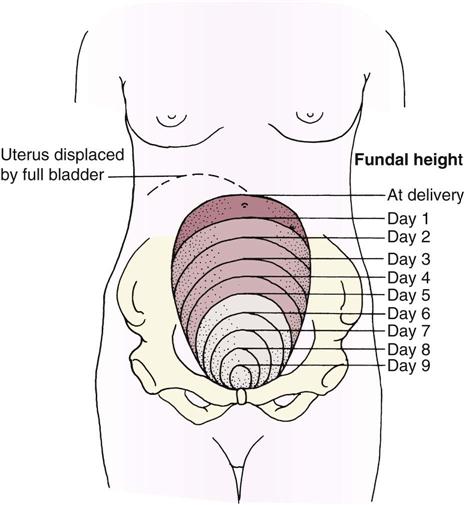

The uterine fundus (the upper portion of the body of the uterus) descends at a predictable rate as the muscle cells contract to control bleeding at the placental insertion site and as the size of each muscle cell decreases. Immediately after the placenta is expelled, the uterine fundus can be felt midline, at or below the level of the umbilicus, as a firm mass (about the size of a grapefruit). After 24 hours the fundus begins to descend about 1 cm (one finger’s width) each day. By 10 days postpartum, it should no longer be palpable (see Skill 9-2). A full bladder interferes with uterine contraction because it pushes the fundus up and causes it to deviate to one side, usually the right side (Figure 9-2).

Afterpains.

Intermittent uterine contractions may cause afterpains similar to menstrual cramps. The discomfort is self-limiting and decreases rapidly within 48 hours postpartum. Afterpains occur more often in multiparas or in women whose uterus was overly distended. Breastfeeding mothers may have more afterpains because infant suckling causes their posterior pituitary to release oxytocin, a hormone that contracts the uterus. Mild analgesics may be prescribed. Aspirin is not used postpartum because it interferes with blood clotting.

Lochia.

Vaginal discharge after delivery, called lochia, is composed of endometrial tissue, blood, and lymph. Lochia gradually changes characteristics during the early postpartum period:

• Lochia rubra is red because it is composed mostly of blood; it lasts for about 3 days after birth.

Lochia has a characteristic fleshy or menstrual odor; it should not have a foul odor. The woman’s fundus should be checked for firmness, because an uncontracted uterus allows blood to flow freely from vessels at the placenta insertion site.

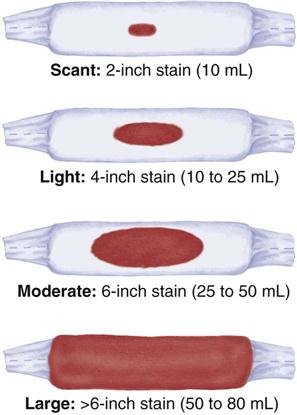

Many facilities use perineal pads that contain cold or warm packs. These pads absorb less lochia, and that fact must be considered when estimating the amount (Skill 9-1). If a mother has excessive discharge of lochia, a clean pad should be applied and checked within 15 minutes. The peripads applied during a given time period are counted or weighed to help determine the amount of vaginal discharge. One gram of weight equals about a 1-mL volume of blood. The nurse should assess the underpads on the bed to determine if bleeding has overflowed onto the bed linen.

The flow of lochia is briefly heavier when the mother ambulates, because lochia pooled in the vagina is discharged when she assumes an upright position. A few small clots may be seen at this time, but large clots should not be present. The quantity of lochia may briefly increase when the mother breastfeeds, because suckling causes uterine contraction. The rate of discharge increases with exercise. Women who had a cesarean birth have less discharge of lochia during the first 24 hours because the uterine cavity was sponged at delivery. The absence of lochia is not normal and may be associated with blood clots retained within the uterus or with infection.

Nursing Care.

The fundus is assessed at routine intervals for firmness, location, and position (Skill 9-2) in relation to the midline. Women who have a higher risk for postpartum hemorrhage (see Chapter 10) should be assessed more often. While doing early assessments, the nurse explains the reason they are done and teaches the woman how to assess her fundus. If her uterus stops descending, she should report that to her birth attendant.

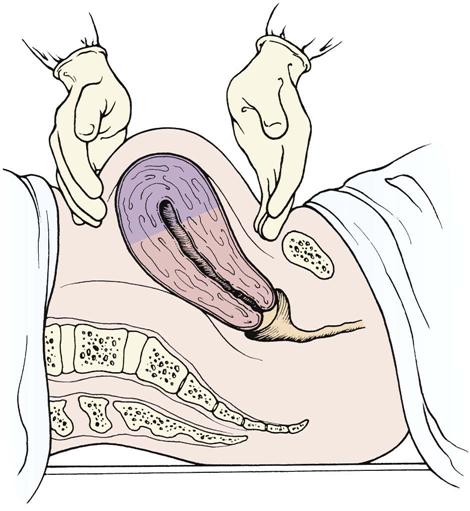

A poorly contracted (soft or boggy) uterus should be massaged until firm to prevent hemorrhage. Lochia flow may increase briefly as the uterus contracts and expels it. It is essential not to push down on an uncontracted uterus to prevent inverting it. If a full bladder contributes to poor uterine contraction, the mother should be assisted to void in the bathroom or on a bedpan if she cannot ambulate. Catheterization may be necessary if she cannot void.

The woman should be taught the expected sequence for lochia changes and the amount she should expect. The woman should report any of the following abnormal characteristics:

• Foul-smelling lochia, with or without fever

• Lochia rubra that persists beyond the third day

• Unusually heavy flow of lochia

• Lochia that returns to a bright red color after it has progressed to serosa or alba

Medications that may be given to stimulate uterine contraction include the following:

• Oxytocin (Pitocin), often routinely given in an intravenous infusion after birth

• Methylergonovine (Methergine), given intramuscularly or orally

An infant suckling at the breast has a similar effect because natural oxytocin release stimulates contractions.

Mild analgesics relieve afterpains adequately for most women. The breastfeeding mother should take an analgesic immediately after breastfeeding to minimize sedation and side effects passing to the newborn. Afterpains persisting longer than the expected time should be reported.

Cervix

The cervix regains its muscle tone but never closes as tightly as during the prepregnant state. Some edema persists for a few weeks after delivery. A constant trickle of brighter red lochia is associated with bleeding from lacerations of the cervix or vagina, particularly if the fundus remains firm.

Vagina

The vagina undergoes a great deal of stretching during childbirth. The rugae, or vaginal folds, disappear, and the walls of the vagina become smooth and spacious. The rugae reappear 3 weeks postpartum. Within 6 weeks the vagina has regained most of its prepregnancy form, but it never returns to the size it was before pregnancy.

Nursing Care.

Couples often are hesitant to ask questions concerning resumption of sexual activity after childbirth, and many resume activity before the 6-week checkup. It is important for the nurse to teach the woman that it is considered safe to resume sexual intercourse when bleeding has stopped and the perineum (episiotomy) has healed. However, the vagina does not lubricate well in the first 6 weeks after childbirth (or longer in the breastfeeding mother). A water-soluble gel such as K-Y or a contraceptive gel can be used for lubrication to make intercourse more comfortable. Instructing the woman to correctly perform the Kegel exercise helps her strengthen muscles involved in urination, bowel function, and vaginal sensations during intercourse.

Perineum

The perineum is often edematous, tender, and bruised. An episiotomy (incision to enlarge the vaginal opening) may have been done, or a perineal laceration may have occurred. Women with hemorrhoids often find that these temporarily worsen during the pressure of birth.

Nursing Care.

The perineum should be assessed for normal healing and signs of complications (Skill 9-3). The REEDA acronym helps the nurse remember the five signs to assess.

Comfort and hygienic measures are the focus of nursing care and patient teaching. An ice pack or chemical cold pack is applied for the first 12 to 24 hours to reduce edema and bruising and numb the perineal area. A disposable rubber glove filled with ice chips and taped shut at the wrist can also be used. The cold pack should be covered with a paper cover or a washcloth. When the ice melts, the cold pack is left off for 10 minutes before applying another for maximum effect. In some cultures, women believe that heat has healing properties and may resist the use of an ice pack.

After 24 hours, heat in the form of a chemical warm pack, a bidet, or a sitz bath increases circulation and promotes healing. The sitz bath may circulate either cool or warm water over the perineum to cleanse the area and increase comfort. Sitting in 4 to 5 inches of water in a bathtub has a similar effect (Skill 9-4).

The woman is taught to do perineal care after each voiding or bowel movement to cleanse the area without trauma. A plastic bottle (peribottle) is filled with warm water, and the water is squirted over the perineum in a front-to-back direction. The perineum is blotted dry. Perineal pads should be applied and removed in the same front-to-back direction to prevent fecal contamination of the perineum and vagina (Skill 9-5).

Topical and systemic medications may be used to relieve perineal pain. Topical perineal medications reduce inflammation or numb the perineum. Commonly prescribed medications include the following:

In addition to these topical medications, witch hazel pads (Tucks) and sitz baths reduce the discomfort of hemorrhoids.

To reduce pain when sitting, the mother can be taught to squeeze her buttocks together as she lowers herself to a sitting position and then to relax her buttocks. An air ring, or “donut,” takes pressure off the perineal area when sitting. The mother should inflate the ring about halfway. (If it is inflated fully, she tends to topple off when she sits on it.) A small eggcrate pad is an alternative to the air ring.

Return of Ovulation and Menstruation

The production of placental estrogen and progesterone stops when the placenta is delivered, causing a rise in the production of follicle-stimulating hormone and the return of ovulation and menstruation. Menstrual cycles resume in about 6 to 8 weeks if the woman is not breastfeeding. The early menstrual periods may or may not be preceded by ovulation. Return of ovulation is more delayed in the breastfeeding mother. However, ovulation may occur at any time after birth, with or without menstrual bleeding, and pregnancy is possible. Therefore pregnancy can occur unless birth control is practiced. Regular oral contraceptives are not used during early breastfeeding, but a minipill can be used effectively.

Breasts

Both nursing and nonnursing mothers experience breast changes after birth. Assessments for both types of mothers are similar, but nursing care differs.

Changes in the Breasts.

For the first 2 or 3 days the breasts are full but soft. By the third day the breasts become firm and lumpy as blood flow increases and milk production begins. Breast engorgement may occur in both nursing and nonnursing mothers. The engorged breast is hard, erect, and very uncomfortable. The nipple may be so hard that the infant cannot easily grasp it. The breasts of the nonnursing mother return to their normal size in 1 to 2 weeks.

Nursing Care.

At each assessment the nurse checks the woman’s breasts for consistency, size, shape, and symmetry. The nipples are inspected for redness and cracking, which makes breastfeeding more painful and offers a port of entry for microorganisms. Flat or inverted nipples make it more difficult for the infant to grasp the nipple and suckle.

Both nursing and nonnursing mothers should wear a bra to support the heavier breasts. The bra should firmly support the nursing mother’s breasts but not be so tight that it impedes circulation. Some nonnursing mothers may prefer to wear an elastic binder to suppress lactation.

The nonnursing mother should avoid stimulating her nipples, which stimulates lactation. She should wear a bra at all times to avoid having her clothing brush back and forth over her breasts and should stand facing away from the water spray in the shower.

The nipples should be washed with plain water to avoid the drying effects of soap, which can lead to cracking. The nonnursing woman should minimize stimulation when washing her breasts. Breastfeeding is discussed on pp. 221–229.

Cardiovascular System

Cardiac Output and Blood Volume

Because of a 50% increase in blood volume during pregnancy, the woman tolerates the following normal blood loss at delivery:

Despite the blood loss there is a temporary increase in blood volume and cardiac output because blood that was directed to the uterus and the placenta returns to the main circulation. Added fluid also moves from the tissues into the circulation, further increasing her blood volume. The heart pumps more blood with each contraction (increased stroke volume), leading to bradycardia. After the initial postbirth excitement wanes, the pulse rate may be as low as 50 to 60 beats/min for about 48 hours after birth. To reestablish normal fluid balance, the body rids itself of excess fluid in the following two ways:

Coagulation

Blood clotting factors are higher during pregnancy and the puerperium, yet the woman’s ability to lyse (break down and eliminate) clots is not increased. Therefore she is prone to blood clot formation, especially if there is stasis of blood in the venous system. This situation is more likely to occur if the woman has varicose veins, has had a cesarean birth, or must delay ambulation. Dyspnea (difficult breathing) and tachypnea (rapid breathing) are hallmark signs of a pulmonary embolus and necessitates immediate medical intervention.

Blood Values

The massive fluid shifts just described affect blood values such as hemoglobin and hematocrit, making them difficult to interpret during the early puerperium. Fluid that shifts into the bloodstream dilutes the blood cells, which lowers the hematocrit. As the fluid balance returns to normal, the values are more accurately interpreted, usually by 8 weeks postpartum.

The white blood cell (leukocytes) count may rise as high as 12,000 to 20,000/mm3, a level that would ordinarily suggest infection. The increase is in response to inflammation, pain, and stress, and it protects the mother from infection as her tissues heal. The white blood cell count returns to normal by 12 days postpartum.

Chills

Many mothers experience tremors that resemble shivering or “chills” immediately after birth. This tremor is thought to be related to a sudden release of pressure on the pelvic nerves and a vasomotor response involving epinephrine (adrenaline) during the birth process. Most women will deny feeling cold. These tremors or “chills” stop spontaneously within 20 minutes. The nurse should reassure the woman and cover her with a warm blanket to provide comfort. Chills accompanied by fever after the first 24 hours suggest infection and should be reported.

Orthostatic Hypotension

Resistance to blood flow in the vessels of the pelvis drops after childbirth. As a result, the woman’s blood pressure falls when she sits or stands, and she may feel dizzy or lightheaded or may even faint. Guidance and assistance are needed during early ambulation to prevent injury.

Nursing Care.

After the fourth stage, vital signs are taken every 4 hours for the first 24 hours. The temperature may rise to 38° C (100.4° F) in the first 24 hours. A higher temperature or the persistence of a temperature elevation for more than 24 hours suggests infection. The pulse rate helps to interpret temperature and blood pressure values. Because of the normal postpartum bradycardia, a high pulse rate often indicates infection or hypovolemia.

If diaphoresis bothers the woman, she should be reminded that it is temporary. The nurse should help her shower or take a sponge bath and provide dry clothes and bedding.

The nurse checks for the presence of edema in the lower extremities, hands, and face. Edema in the lower extremities is common, as it is during pregnancy. Edema above the waist is more likely to be associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, which can continue during the early postpartum period.

The woman’s legs should be checked for evidence of thrombosis at each assessment, looking for a reddened, tender area (superficial vein) or edema, pain and, sometimes, pallor (deep vein). Homans sign (calf pain when the foot is passively dorsiflexed) is of limited value in identifying thrombosis in the postpartum phase (see Chapter 10). Early and regular ambulation reduces the venous stasis that promotes blood clots.

Urinary System

Kidney function returns to normal within a month after birth. A decrease in the tone of the bladder and ureters as a result of pregnancy combined with intravenous fluids administered during labor may cause the woman’s bladder to fill quickly but empty incompletely during the postpartum period. This can lead to postpartum hemorrhage when the full bladder displaces the uterus, or a possible urinary tract infection because of stasis of the urine in the bladder.

Nursing Care.

The nurse should regularly assess the woman’s bladder for distention. The bladder may not feel full to her, yet the uterus is high and deviated to one side. If she can ambulate, the mother should go to the bathroom and urinate. The first two to three voidings after birth or after catheter removal are measured. Women who receive intravenous infusions or have an indwelling catheter continue to have their urine output measured until the infusion and/or catheter are discontinued. The following measures may help a woman to urinate:

• Provide as much privacy as possible.

• Remain near the woman, but do not rush her by constantly asking her if she has urinated.

• Have the woman place her hands in warm water.

Some discomfort with early urination is expected because of the edema and trauma in the area. However, continued burning or urgency of urination suggests bladder infection. High fever and chills may occur with kidney infection.

Gastrointestinal System

The gastrointestinal system resumes normal activity shortly after birth when progesterone decreases. The mother is usually hungry after the hard work and food deprivation of labor. The nurse should expect to provide food and water to a new mother often!

Constipation may occur during the postpartum period owing to several factors:

• Medications may slow peristalsis.

• Slight dehydration and little food intake during labor make the feces harder.

Nursing Care.

The mother is encouraged to drink lots of fluids, add fiber to her diet, and ambulate. A stool softener such as docusate calcium (Surfak) or docusate sodium (Colace) is usually ordered. These measures are generally sufficient to correct the problem. Because constipation is a common problem during pregnancy, measures she has used to relieve it are discussed at that time and efforts are made to build on her knowledge. A common laxative is bisacodyl (Dulcolax), given orally or as a suppository when a laxative is indicated.

Integumentary System

Hyperpigmentation of the skin (“mask of pregnancy,” or chloasma, and the linea nigra) disappears as hormone levels decrease. Striae (“stretch marks”) do not disappear but fade from reddish purple to silver.

Musculoskeletal System

The abdominal wall has been greatly stretched during pregnancy and may now have a “doughy” appearance. Many women are dismayed to discover that they still look pregnant after they give birth. They should be reassured that time and exercise can tighten their lax muscles. Also, some women have diastasis recti, in which the longitudinal abdominal muscles that extend from the chest to the symphysis pubis are separated. Abdominal wall weakness may remain for 6 to 8 weeks and contribute to constipation. Hypermobility of the joints usually stabilizes within 6 weeks, but the joints of the feet may remain separated and the new mother may notice an increase in shoe size. The center of gravity of the body returns to normal when the enlarged uterus returns to its prepregnant size.

A woman can usually begin light exercises as soon as the first day after vaginal birth. Women who have undergone a cesarean birth may wait longer. The woman should consult her health care provider for specific instructions about exercise. Common postpartum exercises include the following:

Immune System

Prevention of blood incompatibility and infection are addressed in the postpartum period according to each woman’s specific needs.

Rho(D) Immune Globulin

The woman’s blood type and Rh factor and antibody status are determined on an early prenatal visit or on admission if she did not have prenatal care. The Rh-negative mother should receive a dose of Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) within 72 hours after giving birth to an Rh-positive infant. This prevents sensitization to Rh-positive erythrocytes that may have entered her bloodstream when the infant was born. RhoGAM is given to the mother, not the infant, by intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle. The woman receives an identification card stating that she is Rh negative and has received RhoGAM on that date.

Rubella (German Measles) Immunization

Rubella titers are done early in pregnancy to determine if a woman is immune to rubella. A titer of 1:8 or greater indicates immunity to the rubella virus. The mother who is not immune is given the vaccine in the immediate postpartum period. The vaccine prevents infection with the rubella virus during subsequent pregnancies, which could cause birth defects. A signed informed consent is usually required to administer the rubella vaccine.

The rubella vaccine is given subcutaneously in the upper arm. The woman should not get pregnant for the next 1 month. The vaccine should not be administered if she is sensitive to neomycin. Women vaccinated during the postpartum period may breastfeed without adverse affects on the newborn (CDC, 2009).

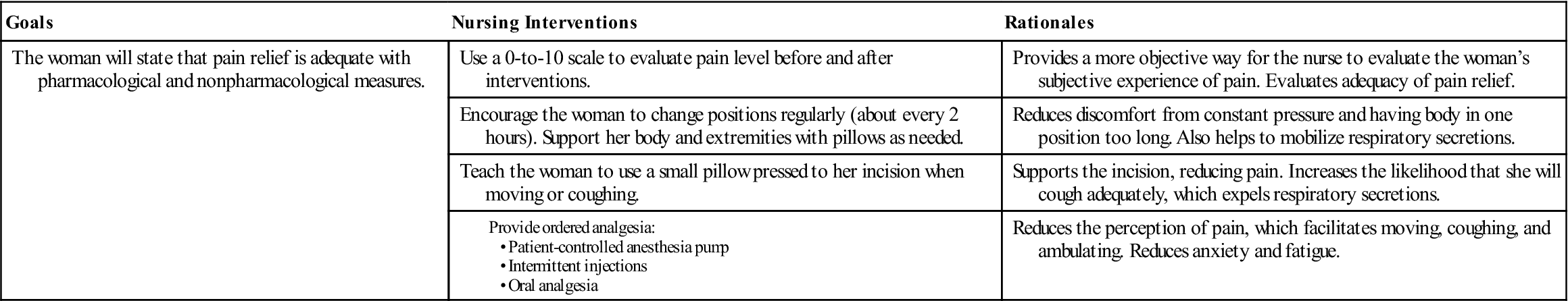

Adaptation of Nursing Care following Cesarean Birth

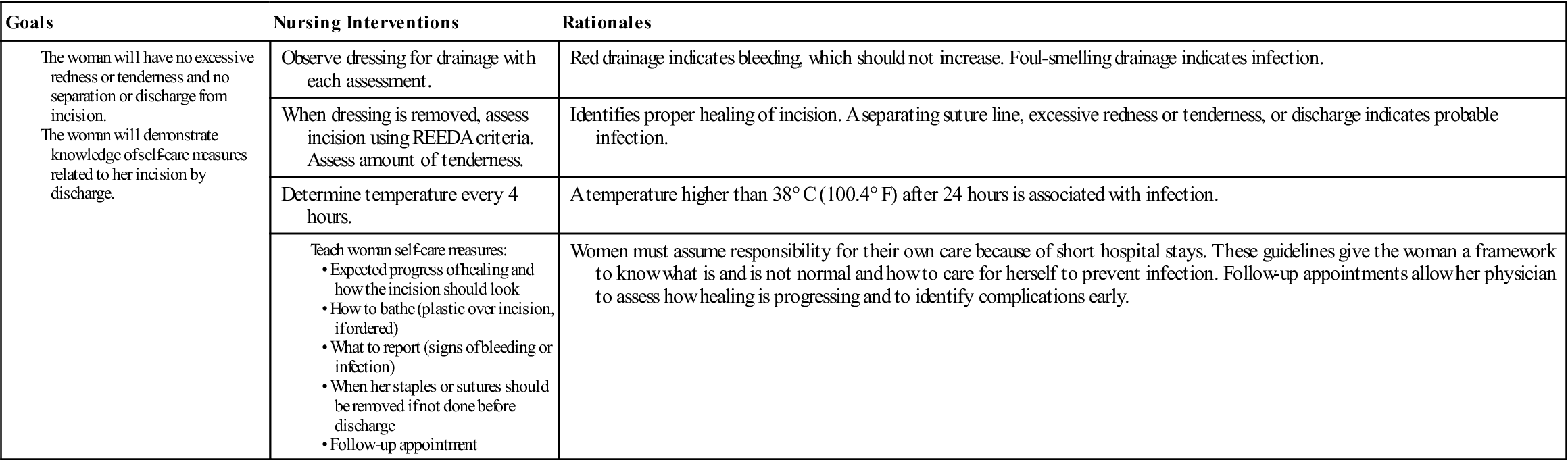

The woman who has a cesarean birth has had surgery as well as given birth. Many of her reactions to the surgical birth depend on whether she expected it. The woman who had an unexpected, emergency cesarean often has many questions about what happened to her and why, because there was no time to answer these questions at the time of birth. In addition, her anxiety may have limited her ability to comprehend any explanations given. Occasionally a woman may feel that she failed if she was unable to give birth after laboring. Terms such as failed induction and failure to progress imply that the woman herself was not competent in some way. Some variations of normal postpartum care are needed for the woman who has a cesarean birth (Nursing Care Plan 9-1).

Uterus

The nurse should check the fundus as on any new mother; it descends at a similar rate. Checking her fundus when a woman has a transverse skin incision is not much different from checking the woman who had vaginal birth. If she has a vertical skin incision, the nurse should gently “walk” the fingers toward the fundus from the side to her abdominal midline. If the fundus is firm and at its expected level, no massage is necessary.

Lochia

Lochia is checked at routine assessment intervals, which vary with the time since birth. The quantity of lochia is generally less immediately after cesarean birth because surgical sponges have removed the contents of the uterus.

Dressing

The dressing should be checked for drainage as with any surgical patient. When the dressing is removed, the incision is assessed for signs of infection. The wound should be clean and dry, and the staples should be intact. The REEDA acronym previously described is a good way to remember key items to check on an incision: redness, edema, ecchymosis, drainage, and approximation. Staples may be removed and Steri-Strips applied shortly before hospital discharge on the third day. If a woman leaves earlier, the staples may be removed in her health care provider’s office.

The woman can shower as soon as she can ambulate reliably. A shower chair reduces the risk for fainting. The dressing or incision can be covered with a plastic wrap, and the edges secured with tape. The woman should be told to position herself with her back to the water stream. The dressing is changed after the woman finishes her shower. A similar technique can be used to cover an intravenous infusion site. If the infusion site is in her hand, a glove can cover it.

Urinary Catheter

An indwelling urinary catheter is generally removed within 24 hours of delivery. Urine is observed for blood, which may indicate trauma to the bladder during labor or surgery. The blood should quickly clear from the urine as diuresis occurs. Intake and output are measured until both the intravenous infusion and the catheter are discontinued. The first two to three voidings are measured, or until the woman urinates at least 150 mL. The nurse should observe and teach the woman to observe for the following signs of urinary tract infection because use of a catheter increases this risk:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree