Theory of bureaucratic caring

Sherrilyn Coffman

“Improved patient safety, infection control, reduction in medication errors, and overall quality of care in complex bureaucratic health care systems cannot occur without knowledge and understanding of complex organizations, such as the political and economic systems, and spiritual-ethical caring, compassion and right action for all patients and professionals.”

(M. Ray, personal communication, May 15, 2012).

Marilyn Anne Ray

1938 to present

Credentials of the theorist

Marilyn Anne (Dee) Ray was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and grew up in a family of six children. When Ray was 15, her father became seriously ill, was hospitalized, and almost died. A nurse saved his life. Marilyn decided that she would become a nurse so that she could help others and perhaps save lives, too.

Photo credit: M. Dauley, Artistic Images, Littleton, CO.

In 1958, Marilyn Ray graduated from St. Joseph Hospital School of Nursing, Hamilton, and left for Los Angeles, California. She worked at the University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center on a number of units, including obstetrics and gynecology, emergency department, and cardiac and critical care with adults and children from vulnerable populations. While working with African Americans and Latinos, Ray began to see how important cultures were in the development of people’s views about nursing and the world.

In 1965, Ray returned to school for her BSN and MSN in maternal-child nursing at the University of Colorado School of Nursing. There she met Dr. Madeleine Leininger, who was the first nurse anthropologist and the Director of the Federal Nurse-Scientist program. Through her mentorship, Leininger influenced Ray’s life. Ray took a special interest in nursing, anthropology, childhood, and culture. She studied organizations as small cultures, and her graduate school project involved the study of a children’s hospital as a small culture. While at the University of Colorado, Ray practiced with children and adults in critical care and renal dialysis, and in occupational health nursing with family-centered care.

In the mid 1960s, Ray became a citizen of the United States and shortly afterward was commissioned as an officer in the United States Air Force Reserve, Nurse Corps (and Air National Guard). She graduated as a flight nurse from the School of Aerospace Medicine at Brooks Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas, and served as an aero-medical evacuation nurse. She cared for combat casualties and other patients on board various types of aircraft during the Viet Nam war. Ray served longer than 30 years in different positions in the U.S. Air Force—flight nurse, clinician, administrator, educator, and researcher—and held the rank of colonel. Her interest in space nursing stimulated her to attend the program for educators at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. She remains a charter member of the Space Nursing Society. In 1990, Ray was the first nurse to go to the Soviet Union with the Aerospace Medical Association, when the former USSR opened its space operations to American space engineers and physicians. Ray was called to active duty during the Persian Gulf War in 1991 and was assigned to Eglin Air Force Base, Valparaiso, Florida, where she orchestrated discharge planning and conducted research in the emergency department.

Ray is the recipient of a number of medals, including Air Force commendation medals for nursing education and research developments received during her Air Force career. Most notably, in 2000 she received the Federal Nursing Services Essay Award from the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States for research on the impact of TRICARE/Managed Care on Total Force Readiness. This award recognized her accomplishments in a research program on economics and the nurse-patient relationship that received nearly $1 million from the TriService Military Nursing Research Council. In 2008, she received the TriService Nursing Research Program Coin for excellence in nursing research.

Ray’s first nursing faculty positions were at the University of California San Francisco and the University of San Francisco with Glaser and Strauss, authors of the grounded theory method. She was intrigued by the study of nursing as a culture and had opportunities to teach students from various American and Asian cultures. In 1971, she traveled to Mexico with colleagues to study anthropology and health.

From 1973 to 1977, Ray returned to Canada to be with her family. She joined the nursing faculty at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and taught in the family nurse practitioner program. This was an exciting time, because the McMaster University Health Sciences Center was initiating evidence-based teaching, education, and practice. Ray completed a Master of Arts in Cultural Anthropology at McMaster University and studied human relationships, decision making and conflict, and the hospital as an organizational culture. She then received a letter from Dr. Leininger asking her to apply for the first transcultural nursing doctoral program at the University of Utah. At the university, Ray’s doctoral dissertation (1981a) was a study on caring in the complex hospital organizational culture. From this research, the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring, the focus of this chapter, was developed.

During her doctoral studies, Ray married James L. Droesbeke, her inspiration and friend, and the love of her life. He was a constant source of support and help to her over the course of her career until his untimely death from cancer in 2001. After completing her doctorate in 1981, Ray rejoined the University of Colorado School of Nursing. At the University of Colorado, Ray worked with Dr. Jean Watson, who developed the theory and practice of human caring in nursing. With Watson and other scholars, Ray founded the International Association for Human Caring, which awarded her its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008. In the 1980s, At the University of Colorado, Ray continued her study of phenomenology and qualitative research approaches and directed dissertation work.

In 1989, Ray accepted an appointment by Dean Anne Boykin as the Christine E. Lynn Eminent Scholar at Florida Atlantic University, College of Nursing, a position held until 1994. Florida Atlantic University developed the Center for Caring, which has been housing caring archives since the inception of the International Association for Human Caring in 1977. Ray held the position of Yingling Visiting Scholar Chair at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing from 1994 to 1995, and she was a visiting professor at the University of Colorado from 1989 to 1999. Ray has been visiting professor at universities in Australia, New Zealand, and Thailand, advancing the teaching and research of human caring (Ray 1994b, 2000, 2010a, 2010b; Ray & Turkel, 2000, 2010). She authored several theoretical and research publications in transcultural caring, transcultural ethics, and caring inquiry.

Ray continues as Professor Emeritus at the Florida Atlantic University Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing as a part-time faculty member in the PhD program and faculty mentor. Ray’s interest in transcultural nursing remains a theme in her research, teaching, and practice. With Dr. Sherrilyn Coffman, she completed a grounded theory research study of high-risk pregnant African-American women (Coffman & Ray, 1999, 2002). Learning about vulnerable populations gave Ray a deeper understanding of their needs, particularly the importance of access to health care and caring communities. Ray was vice president of Floridians for Health Care (universal health care) from 1998 to 2000. She is a Certified Transcultural Nurse and a member of the International Transcultural Nursing Society. She has made international presentations in China, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Finland, England, Switzerland, Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1984, Ray received the Leininger Transcultural Nursing Award for excellence in transcultural nursing. In 2005, she was named a Transcultural Nursing Scholar by the International Transcultural Nursing Society. Ray is listed in Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in the World and gave a paper in 2010 on caring organizations at the World Universities Forum in Davos, Switzerland (Ray, 2010c). She attended a program of study at the United Nations related to implementation of the 2015 Millennium goals. Ray serves on review boards of the Journal of Transcultural Nursing and Qualitative Health Research. She also published Transcultural Caring Dynamics in Nursing and Health Care (Ray, 2010a) and, with co-editors, Nursing, Caring, and Complexity Science: For Human-Environment Well-Being, which received a 2011 American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year award.

Ray’s research interests continue to focus on nurses, nurse administrators, and patients in critical care and intermediate care, and in nursing administration in complex hospital organizational cultures. She developed research with Dr. Marian Turkel to study the nurse-patient relationship as an economic resource, funded by the TriService Nursing Research Program (Turkel & Ray, 2000, 2001, 2003). With Turkel, Ray has published about complex caring relational theory, organizational transformation through caring and ethical choice making, instrument development on organizational caring, economic and political caring, and caring organization creation. They recently proposed renaming the nursing process to the language of caring in Nursing Science Quarterly (Turkel, Ray, & Kornblatt, 2012). Continued involvement at Florida Atlantic University has given Ray opportunities to influence complex organizations and caring organizations and environments in local, national, and global contexts. Her contributions to nursing education were recognized in 2005 with an honorary degree from Nevada State College and in 2007 with the Distinguished Alumna Award from University of Utah College of Nursing.

Theoretical sources

Ray’s interest in caring as a topic of nursing scholarship was stimulated by her work with Leininger beginning in 1968, which focused on transcultural nursing and ethnographic-ethnonursing research methods. She used ethnographic methods in combination with phenomenology and grounded theory to generate substantive and formal grounded theories, resulting in the overarching Theory of Bureaucratic Caring (Ray, 1981a, 1984, 1989, 1994b, 2010 b, 2011), which focuses on nursing in complex organizations such as hospitals. She distinguishes organizations as cultures based on anthropological study of how people behave in communities and the significance or meaning of work life (Louis, 1985). Organizational cultures, viewed as social constructions, are formed symbolically through meaning in interaction (Smircich, 1985).

Ray’s work (1981b, 1989, 2010b; Moccia, 1986) was influenced by Hegel, who posited the interrelationship among thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. In Ray’s theory, the thesis of caring (humanistic, spiritual, and ethical) and the antithesis of bureaucracy (technological, economic, political, and legal) are reconciled and synthesized into the unitive force, bureaucratic caring. The synthesis, as a process of becoming, is a transformation that continues to repeat itself always changing, emerging, and transforming.

As she revisited and continued to develop her formal theory, Ray (2001, 2006; Ray & Turkel, 2010) discovered that her study findings fit well with explanations from chaos theory. Chaos theory describes simultaneous order and disorder, and order within disorder. An underlying order or interconnectedness exists in apparently random events (Peat, 2002). Mathematical studies have shown that what may seem random is actually part of a larger pattern. Application of this theory to organizations demonstrates that within a state of chaos, the system is held within boundaries that are well ordered (Wheatley, 2006). Furthermore, chaos is necessary for new creative ordering. The creative process as described by Briggs & Peat is as follows:

“…. when we enter the vital turbulence of life, we realize that, at bottom, everything is always new. Often we have simply failed to notice this fact. When we’re being creative, we take notice.”

(Briggs & Peat, 1999, p. 30)

Ray compares change in complex organizations with this creative process and challenges nurses to step back and renew their perceptions of everyday events, to discover the embedded meanings. This is particularly important during organizational change. Complexity is a broader concept than chaos and focuses on wholeness or holonomy. Complex systems, such as organizations, have many agents that interact with each other in multiple ways. As a result, these systems are dynamic and always changing. Systems behave in nonlinear fashion because they do not react proportionately to inputs. For example, a simple intervention such as asking a colleague for help may be accommodated easily or may be seen as unreasonable on a busy day, making the behavior of complex systems impossible to predict (Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011; Vicenzi, White, & Begun, 1997). Nevertheless, chaos exists only because the entire system is holistic. Briggs and Peat (1999, pp. 156-157) describe this “chaotic wholeness” as “full of particulars, active and interactive, animated by nonlinear feedback and capable of producing everything from self-organized systems to fractal self-similarity to unpredictable chaotic disorder.” Their ideas influenced Ray’s ongoing development of bureaucratic caring theory, which suggests that multiple system inputs are interconnected with caring in the organizational culture (Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011; Ray, Turkel, & Cohn, 2011). Ray’s idea of the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring as holographic was influenced by the revolution taking place in science based on the holographic worldview (Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011; Ray, 2001, 2006; 2010a; Ray & Turkel, 2010). The discovery of interconnectedness among apparently unrelated subatomic events has intrigued scientists. Scientists concluded that systems possess the capacity to self-organize; therefore, attention is shifting away from describing parts and instead is focusing on the totality as an actual process (Wheatley, 2006). The conceptualization of the hologram portrays how every structure interpenetrates and is interpenetrated by other structures—so the part is the whole, and the whole is reflected in every part (Talbot, 1991).

The hologram has provided scientists with a new way of understanding order. Bohm has conceptualized the universe as a kind of giant, flowing hologram (Talbot, 1991; Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011). He asserted that our day-to-day reality is really an illusion, like a holographic image. Bohm termed our conscious level of existence explicate, or unfolded order, and the deeper layer of reality of which humans are usually unaware implicate, or enfolded order. In the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring, Ray compares the health care structures of political, legal, economic, educational, physiological, social-cultural, and technological with the explicate order and spiritual-ethical caring with the implicate order. An example might be a case manager’s decisions about obtaining resources for a client’s care in the home. At first, explicate structures such as the legal managed care contract or the physical needs of the client might appear to provide enough information. However, through the case manager’s caring relationship with the client, implicate issues may emerge, such as the client’s values and desires. In truth, nursing situations involve an endless enfolding and unfolding of information that may be viewed as explicate and implicate order, and important to consider in the decision-making process.

Making things work in a health care organizational system requires knowledge and understanding of bureaucracy, which is rigid, and the complexity of change. Bureaucracy and complexity may seem like the antithesis of each other, but, in reality, the structure of bureaucracy (illuminating the political, economic, legal, and technological systems in organizations) works in conjunction with the complex relational process of networks to co-create patterns of human behavior and patterns of caring. Both bureaucracy and complexity influence the ways in which diverse participants describe and intuitively live out their life world experience in the system. No one thing or person in a system is independent; rather, they are interdependent. The system is holographic as the whole and the part are intertwined. Thus, bureaucracy and complexity co-create and transform each other. The Theory of Bureaucratic Caring is a representation of the relatedness of system and caring factors.

Use of empirical evidence

The Theory of Bureaucratic Caring was generated from qualitative research involving health professionals and clients in the hospital setting. This research focused on caring in the organizational culture and first appeared in the doctoral dissertation in 1981, and in other literature in 1984 and 1989. The purpose of the dissertation research was to generate a theory of the dynamic structure of caring in a complex organization. Methods used were grounded theory, phenomenology, and ethnography to elicit the meaning of caring to study participants.

The grounded theory approach is a qualitative research method that uses a systematic set of procedures to develop an inductive theory of a social process (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The process results in the evolution of substantive theory (caring data generated from experience) and formal theory (integrated synthesis of caring and bureaucratic structures).

Ray studied caring in all areas of a hospital, from nursing practice to materials management to administration, including nursing administration. More than 200 respondents participated in the purposive and convenience sample. The principal question asked was “What is the meaning of caring to you?” Through dialogue, caring evolved from in-depth interviews, participant observation, caregiving observation, and documentation (Ray, 1989).

Ray’s discovery of bureaucratic caring began as a substantive theory and evolved to a formal theory. The substantive theory emerged as Differential Caring, that the meaning of caring differentiates itself by its context. Dominant caring dimensions vary in terms of areas of practice or hospital units. For example, an intensive care unit has a dominant value of technological caring (e.g., monitors, ventilators, treatments, and pharmacotherapeutics), and an oncology unit has a value of a more intimate, spiritual caring (e.g., family focused, comforting, compassionate). Staff nurses valued caring in relation to patients, and administrators valued caring in relation to the system, such as the economic well-being of the hospital.

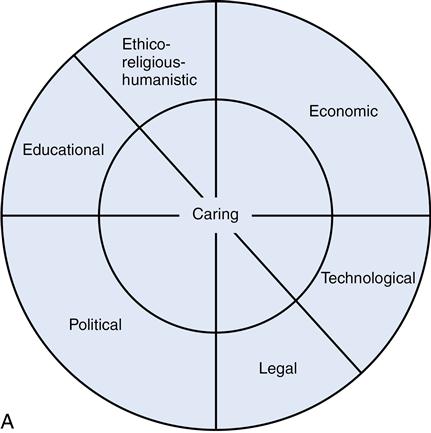

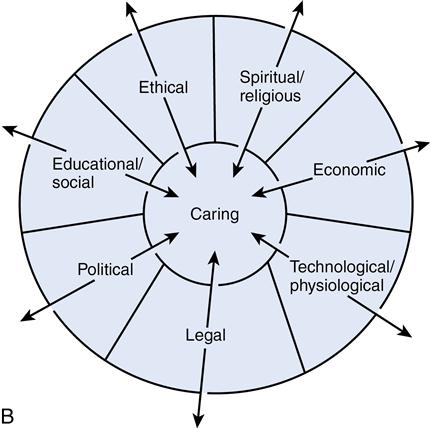

The formal Theory of Bureaucratic Caring symbolized a dynamic structure of caring. This structure emerged from the dialectic between the thesis of caring as humanistic (i.e., social, education, ethical, and religious-spiritual structures) and the antithesis of caring as bureaucratic (i.e., economic, political, legal, and technological structures). The dialectic of caring illustrates that everything is interconnected and that the organization is a macrocosm of the culture.

The evolution of Ray’s theory is illustrated in Figure 8-1, with diagrams of the bureaucratic caring structure published in 1981 and 1989. In the original grounded theory (see Figure 8-1, A). political and economic structures occupied a larger dimension to illustrate their increasing influence on the nature of institutional caring (Ray, 1981a). Subsequent research conducted in intensive care and intermediate care units (Ray, 1989) emphasized the differential nature of caring, as seen through its competing structures of political, legal, economic, technological-physiological, spiritual-religious, ethical, and educational-social elements (see Figure 8-1, B). In her 1987 article on technological caring, Ray noted that “critical care nursing is intensely human, moral, and technocratic” (p. 172). Ray encouraged other researchers to study this area to enhance nursing’s understanding of the advantages and limitations of technology in critical care. The Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing journal recognized Ray as Researcher of the Year for her groundbreaking work.

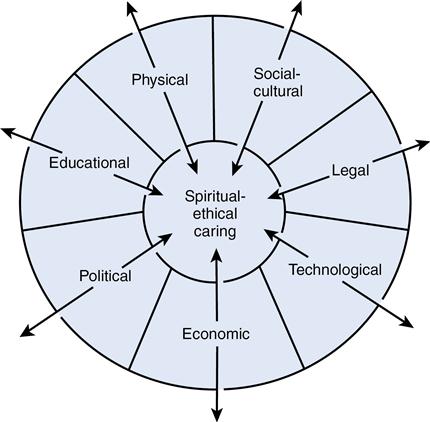

With continued reflection and analysis, combined with research on the economics of the nurse-patient relationship, Ray began to illuminate the ethical-spiritual realm of nursing (Figure 8-2) (Ray, 2001). Spiritual-ethical caring became a dominant modality because of discoveries that focused on the nurse-patient relationship. Qualitatively different systems, such as political, economic, social-cultural, and physiological, when viewed as open and interactive, are whole and operate through the choice making of nurses (Davidson & Ray, 1991; Ray, 1994a). Spiritual-ethical caring suggests how choice making for the good of others can be accomplished in nursing practice.

Ray’s research reveals that in complex organizations, nursing as caring is practiced and lived out at the margin between the humanistic-spiritual dimension and the systemic dimension. These findings are consistent with worldviews from the science of complexity, which propose that antithetical phenomena coexist (Briggs & Peat, 1999; Ray, 1998). Thus, technological and humanistic systems exist together. Complexity theory explains the resolution of the paradox between differing systems (thesis and antithesis) represented in the synthesis or the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring.

In summary, the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring emerged using a grounded theory methodology, blended with phenomenology and ethnography. The initial theory was examined using the philosophy of Hegel. The theory was revisited in 2001 after continuing research, and examination in light of the science of complexity and chaos theory, resulting in the holographic Theory of Bureaucratic Caring (see Figure 8-2).

Major assumptions

Nursing

Nursing is holistic, relational, spiritual, and ethical caring that seeks the good of self and others in complex community, organizational, and bureaucratic cultures. Dwelling with the nature of caring reveals that love is the foundation of spiritual caring. Through knowledge of the inner mystery of the inspirational life within, love calls forth a responsible ethical life that enables the expression of concrete actions of caring in the lives of nurses. As such, caring is cultural and social. Transcultural caring encompasses beliefs and values of compassion or love and justice or fairness, which has significance in the social realm, where relationships are formed and transformed. Transcultural caring serves as a unique lens through which human choices are seen, and understanding in health and healing emerges. Thus, through compassion and justice, nursing strives toward excellence in the activities of caring through the dynamics of complex cultural contexts of relationships, organizations, and communities (Ray, 2010a; Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011).

Person

A person is a spiritual and cultural being. Persons are created by God, the Mystery of Being, and they engage co-creatively in human organizational and transcultural relationships to find meaning and value (M. Ray, personal communication, May 25, 2004).

Health

Health provides a pattern of meaning for individuals, families, and communities. In all human societies, beliefs and caring practices about illness and health are central features of culture. Health is not simply the consequence of a physical state of being. People construct their reality of health in terms of biology; mental patterns; characteristics of their image of the body, mind, and soul; ethnicity and family structures; structures of society and community (political, economic, legal, and technological); and experiences of caring that give meaning to lives in complex ways. The social organization of health and illness in society (the health care system) determines the way that people are recognized as sick or well. It determines how health professionals and individuals view health and illness. Health is related to the way people in a cultural group or organizational culture or bureaucratic system construct reality and give or find meaning (Helman, 1997; Ray, 2010a).

Environment

Environment is a complex spiritual, ethical, ecological, and cultural phenomenon. This conceptualization of environment embodies knowledge and conscience about the beauty of life forms and symbolic (representational) systems or patterns of meaning. These patterns are transmitted historically and are preserved or changed through caring values, attitudes, and communication. Functional forms identified in the social structure or bureaucracy (e.g., political, legal, technological, and economic) play a role in facilitating understanding of the meaning of caring, cooperation, and conflict in human cultural groups and complex organizational environments. Nursing practice in environments embodies the elements of the social structure and spiritual and ethical caring patterns of meaning (Davidson, Ray, & Turkel, 2011; Ray, 2010a).

Theoretical assertions

Person, nursing, environment, and health are integrated into the structure of the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring. The theory implies a dialectical relationship (thesis, antithesis, synthesis) among humans (person and nurse), the dimension of spiritual-ethical caring, and the structural (nursing, environment) dimensions of the bureaucracy or organizational culture (technological, economic, political, legal, and social). For Ray, the dialectic of caring and bureaucracy is synthesized into a theory of bureaucratic caring. Bureaucratic caring, the synthetic margin between the human and structural dimensions, is where nurses, patients, and administrators integrate person, nursing, health, and environment.

Theoretical assertions within the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring are as follows:

1. The meaning of caring is highly differential, depending on its structures (social-cultural, educational, political, economic, physical, technological, legal). The substantive theory of Differential Caring discovered that caring in nursing is contextual and is influenced by organizational structure or culture. Thus the meaning of caring is varied in the emergency department, intensive care unit, oncology unit, and other areas of the hospital and is influenced by the role and position that a person holds. The meaning of caring emerged as differential because no one definition or meaning of caring was identified (Ray, 1984, 1989; Ray, 2010b). The theoretical statement that describes the substantive theory of Differential Caring is formulated as:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree