Theory development process

Sonya R. Hardin

“Nursing’s potential for meaningful human service rests on the union of theory and practice for its fulfillment.”

(Rogers, 1970, p. viii)

Theory development in nursing is an essential component in nursing scholarship to advance the knowledge of the discipline. The legitimacy of any profession is built on its ability to generate and apply theory (McCrae, 2011, p. 222). Nursing theories that clearly set forth understanding of nursing phenomena (i.e., self care, therapeutic communication, chronic sorrow) guide scholarly development of the science of nursing through research. Once a nursing theory is proposed addressing a phenomenon of interest, several considerations follow, such as its completeness and logic, internal consistency, correspondence with empirical findings, and whether it has been operationally defined for testing. Analyses of these lead logically to the further development of the theory. Scientific evidence accumulates through repeated rigorous research that supports or refutes theoretical assertions and guides modifications or extensions of the theory. Nursing theory development is not a mysterious activity, but a scholarly endeavor pursued systematically. Rigorous development of nursing theories, then, is a high priority for the future of the discipline and the practice of the profession of nursing.

It is important to understand the concept of systematic development since approaches to construction of theory differ. A theory may emerge through deductive, inductive, or retroductive (abductive) reasoning. Deductive reasoning is narrow and goes from general to specific. In the clinical area, nurses often have experience with a general rule and apply it to a patient. Inductive reasoning is much broader and exploratory in nature as one goes from specific to general. Abductive reasoning begins with an incomplete set of observations and proceeds to the likeliest possible explanation for the set. A medical diagnosis is an application of abductive reasoning: given this set of symptoms, what is the diagnosis that would best explain most of them? One aspect they have in common is to approach theory development in a precise, systematic manner, making the stages of development explicit. The nurse who systematically devises a theory of nursing and publishes it for the nursing community to review and debate engages in a process that is essential to advancing theory development. As scholarly work is published in the literature, nurse theoreticians and researchers review and critique the adequacy of the logical processes used in the development of the theory with fresh eyes in relation to practice and available research findings.

Previous author: Sue Marquis Bishop.

Theory components

Development of theory requires understanding of selected scholarly terms, definitions, and assumptions so that scholarly review and analysis may occur. Attention is given to terms and defined meanings to understand the theory development process that was used. Therefore, the clarity of terms, their scientific utility, and their value to the discipline are important considerations in the process.

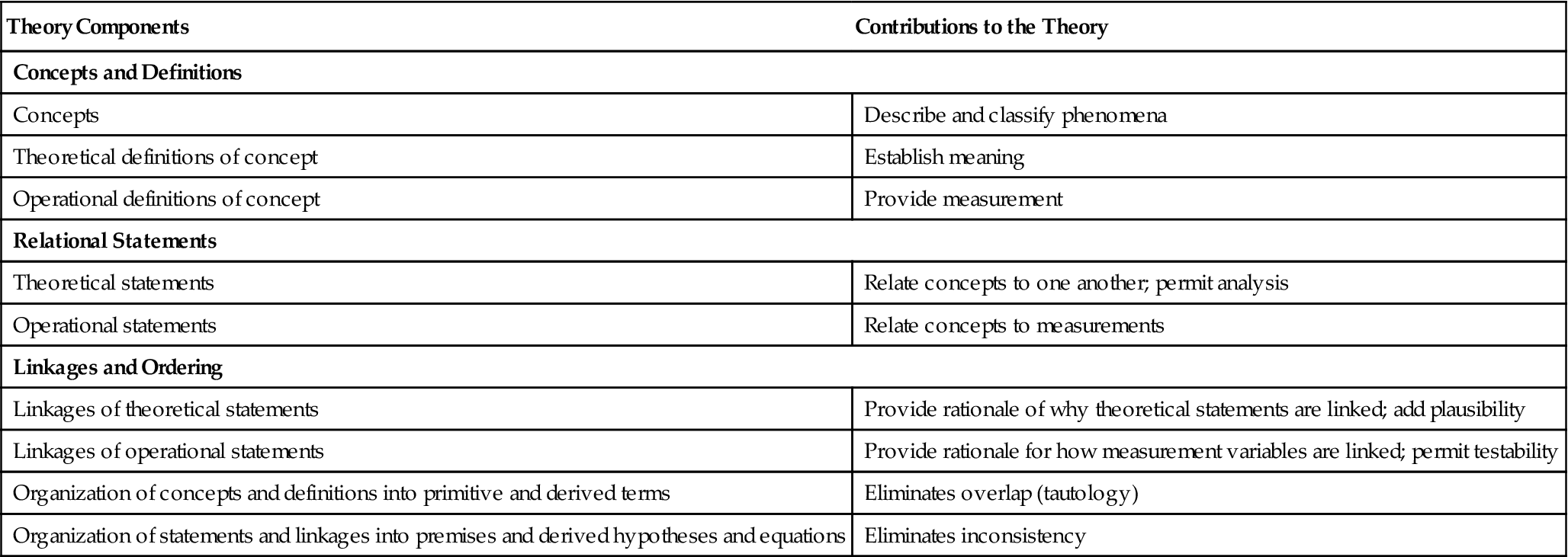

Hage (1972) identified six theory components and specified the contributions they make to theory (Table 3-1). Three categories of theory components are presented as a basis for understanding the function of each element in the theory-building process.

TABLE 3-1

Theory Components and Their Contributions to the Theory

| Theory Components | Contributions to the Theory |

| Concepts and Definitions | |

| Concepts | Describe and classify phenomena |

| Theoretical definitions of concept | Establish meaning |

| Operational definitions of concept | Provide measurement |

| Relational Statements | |

| Theoretical statements | Relate concepts to one another; permit analysis |

| Operational statements | Relate concepts to measurements |

| Linkages and Ordering | |

| Linkages of theoretical statements | Provide rationale of why theoretical statements are linked; add plausibility |

| Linkages of operational statements | Provide rationale for how measurement variables are linked; permit testability |

| Organization of concepts and definitions into primitive and derived terms | Eliminates overlap (tautology) |

| Organization of statements and linkages into premises and derived hypotheses and equations | Eliminates inconsistency |

Modified from Hage, J. (1972). Techniques and problems of theory construction in sociology. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Concepts and definitions

Concepts, the building blocks of theories, classify the phenomena of interest (Kaplan, 1964). It is crucial that concepts are considered within the theoretical system in which they are embedded and from which they derive their meaning, since concepts may have different meanings in various theoretical systems. Scientific progress is based on critical review and testing of a researcher’s work by the scientific community.

Concepts may be abstract or concrete. Abstract concepts are mentally constructed independent of a specific time or place, whereas concrete concepts are directly experienced and relate to a particular time or place (Chinn & Kramer, 2011; Hage, 1972; Reynolds, 1971) (Table 3-2).

TABLE 3-2

Concepts: Abstract versus Concrete

| Abstract Concepts | Concrete Concepts |

| Transport | Stretcher, wheelchair, hospital bed |

| Cardiovascular disease | Stroke, myocardial infarction |

| Telemetry | Electrocardiogram, Holter monitor |

| Loss of relationship | Divorce, widowhood |

| Nurse competency | Cultural, nasogastric tube placement, medication administration |

The stretcher, stroke, wheelchair, and hospital bed are examples of concrete concepts of the abstract concept, transport and the other examples illustrate the concrete to abstract difference. In a given theoretical system, the definition, characteristics, and functioning of a nurse competency clarify more specific instances, such as medication administration nurse competency.

Concepts may be classified as discrete or continuous concepts. This system of labels differentiates types of concept that specify categories of phenomena. A discrete concept identifies categories or classes of phenomena, such as patient, nurse, health, or environment. A student can become a nurse or choose another profession, but he or she cannot become a partial nurse. Phenomena identified as belonging to, or not belonging to, a given class or category may be called nonvariable concepts. Sorting phenomena into nonvariable discrete categories carries the assumption that the associated reality is captured by the classification (Hage, 1972). The amount or degree of the variable is not an issue.

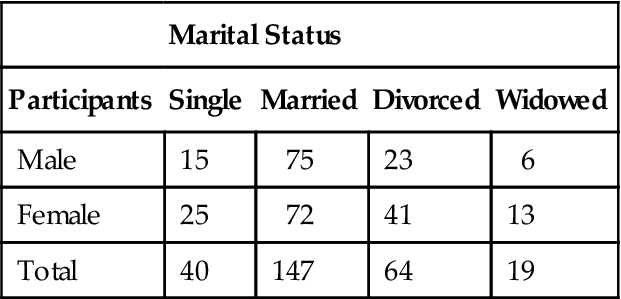

Theories may be used as a series of nonvariable discrete concepts (and subconcepts) to build typologies. Typologies are systematic arrangements of concepts within a given category. For example, a typology on marital status could be partitioned into marital statuses in which a population is classified as married, divorced, widowed, or single. These discrete categories could be partitioned further to permit the classification of an additional variable in this typology. A typology of marital status and gender is shown in Table 3-3. The participants are either one gender or the other since there are no degrees of how much they are in this discrete category. Taking the illustration further, the typology could be partitioned adding the discrete concept of children. Participants would be classified for gender, marital status, and as having or not having children.

TABLE 3-3

Typology of Marital Status and Gender

| Marital Status | ||||

| Participants | Single | Married | Divorced | Widowed |

| Male | 15 | 75 | 23 | 6 |

| Female | 25 | 72 | 41 | 13 |

| Total | 40 | 147 | 64 | 19 |

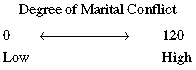

A continuous concept, on the other hand, permits classification of dimensions or gradations of a phenomenon, indicating degree of marital conflict. Marital couples may be classified with a range representing degrees of marital conflict in their relationships from low to high.

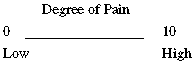

Other continuous concepts that may be used to classify couples might include amount of communication, number of shared activities, or number of children. Examples of continuous concepts used to classify patients are degree of temperature, level of anxiety, or age. Another example is how nurses conceptualize pain as a continuous concept when they ask patients to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10 to better understand their pain threshold or pain experience.

Continuous concepts are not expressed in either/or terms but in degrees on a continuum. The use of variable concepts on a continuum tends to focus on one dimension but does so without assuming that a single dimension captures all of the reality of the phenomenon. Additional dimensions may be devised to measure further aspects of the phenomenon. Instruments may measure a concept and have subscales that measure discrete concepts related to the overall concept. Variable concepts such as ratio of professional to nonprofessional staff, communication flow, or ratio of registered nurses to patients, is used to characterize health care organizations. Although nonvariable concepts are useful in classifying phenomena in theory development, Hage (1972) notes several major breakthroughs in disciplines as the focus shifts from nonvariable to variable concepts, because variable concepts permit the scoring of the phenomenon’s full range of variation.

The development of concepts, then, permits description and classification of phenomena (Hage, 1972). The labeled concept specifies boundaries for selecting phenomena to observe and for reasoning about the phenomena of interest. New concepts may focus attention on new phenomena or facilitate thinking about phenomena in a different way (Hage, 1972). Scholarly analysis of the concepts in nursing theories is a critical beginning step in the process of theoretical inquiry. The concept process continues to flourish with many examples in the nursing literature. See Table 3-4 for references to analyses carried out using different approaches.

TABLE 3-4

Examples of Published Concept Analyses with Different Approaches

| Concept | Approach | Author |

| Spirituality | Chinn & Kramer | Buck (2006) |

| Readiness to change | Chinn & Kramer | Dalton & Gottlieb (2003) |

| Acculturation | Morse | Baker (2011) |

| Ethical sensitivity | Morse | Weaver, Morse, & Mitcham (2008) |

| Disability and aging | Rodgers | Greco & Vincent (2011) |

| Moral distress in neuroscience nursing | Rodgers | Russell (2012) |

| Symptom perception | Schwartz-Barcott & Kim | Posey (2006) |

| Being sensitive | Schwartz-Barcott & Kim | Sayers, K., & de Vries, K. (2008) |

| Work engagement in nursing | Walker & Avant | Bargagliotti (2012) |

| Migration | Walker & Avant | Freeman, Baumann, Blythe, Fisher, & Akhtar-Danesh (2012) |

| Infant distress | Wilson method | Hatfield & Polomano (2012) |

| Social justice | Wilson method | Buettner-Schmidt & Lobo (2012) |

Concept analysis is an important beginning step in the process of theory development to develop a conceptual definition. It is crucial that concepts are clearly defined to reduce ambiguity in the given concept or set of concepts. To eliminate perceived differences in meaning, explicit definitions are necessary. As the theory develops, theoretical and operational definitions provide the theorist’s meaning of the concept and the basis for the empirical indicators. For example, McMahon and Fleury (2012) published a concept analysis on wellness in older adults. Wellness in older adults was theoretically defined as wellness is a purposeful process of individual growth, integration of experience, and meaningful connection with others, reflecting personally valued goals and strengths, and resulting in being well and living values. The concept of wellness in older adults was operationalized as an ever changing process of becoming, integrating, and relating.

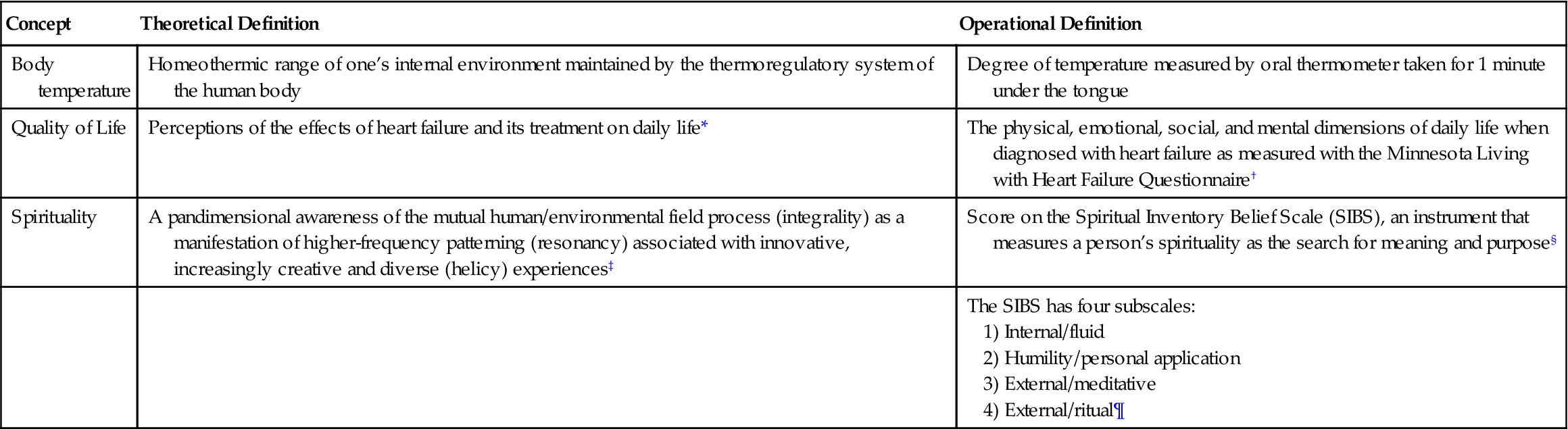

Theories are tested in reality; therefore, the concepts must be linked to operational definitions that relate the concepts to observable phenomena specifying empirical indicators. Table 3-5 provides examples of concepts with their theoretical and operational definitions. These linkages are vital to the logic of the theory, its observation, and its measurement.

TABLE 3-5

Examples of Theoretical and Operational Definitions

| Concept | Theoretical Definition | Operational Definition |

| Body temperature | Homeothermic range of one’s internal environment maintained by the thermoregulatory system of the human body | Degree of temperature measured by oral thermometer taken for 1 minute under the tongue |

| Quality of Life | Perceptions of the effects of heart failure and its treatment on daily life* | The physical, emotional, social, and mental dimensions of daily life when diagnosed with heart failure as measured with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire† |

| Spirituality | A pandimensional awareness of the mutual human/environmental field process (integrality) as a manifestation of higher-frequency patterning (resonancy) associated with innovative, increasingly creative and diverse (helicy) experiences‡ | Score on the Spiritual Inventory Belief Scale (SIBS), an instrument that measures a person’s spirituality as the search for meaning and purpose§ |

| The SIBS has four subscales: |

§Hatch, Burg, Naberhaus, & Hellmich, 1998.

The concept-building process emerges from practice, incorporating the literature and research findings from multiple disciplines. Concepts are built into a conceptual framework and are further refined. A 10-phase process for concept building is described in the literature (Smith & Liehr, 2008; Smith & Liehr, 2012). The process of concept building is guided by patient stories. The 10 phases are as follows: (1) write a meaningful practice story; (2) name the central phenomenon in the practice story; (3) identify a theoretical lens for viewing the phenomenon; (4) link the phenomenon to existing literature; (5) gather a story from someone who has lived the phenomenon; (6) reconstruct the shared story (from Phase 5) and create a mini-saga that captures its message; (7) identify the core qualities of the phenomenon; (8) use the core qualities to create a definition; (9) create a model of the phenomenon; and (10) write a mini-synthesis that integrates the phenomenon with a population to suggest a research direction. The process, which provides the scaffolding for beginning scholars to move from the familiarity of practice to the unfamiliarity of phenomena for research, will be shared with brief examples that demonstrate potential and lessons learned in nearly a decade of use (Smith & Liehr, 2012, p. 65).

Relational statements

Statements in a theory may state definitions or relations among concepts. Whereas definitions provide descriptions of the concept, relational statements propose relationships between and among two or more concepts. Concepts are the building blocks of theory, and theoretical statements are the chains that link the blocks to build theory. Concepts must be connected with one another in a series of theoretical statements to devise a nursing theory.

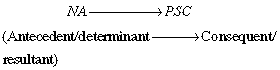

In the connections between variables, one variable may be proposed to influence a second. In this case, the first variable may be viewed as the antecedent or determinate (independent) variable and the second as the consequent or resultant (dependent) variable (Giere, 1997). Zetterberg (1966) concluded that the development of two-variate theoretical statements could be an important intermediate step in the development of a theory. These statements can be reformulated later as the theory evolves or as new information becomes available. An example of an antecedent and a consequent variable is explained looking at the concept of well in older adults, where the antecedents were identified as connecting with others, imagining opportunities, recognizing strengths, and seeking meaning. The consequences identified were living values and being well. These antecedents and consequences were developed from the literature (McMahon & Fleury, 2012).

Theoretical assertions are either a necessary or sufficient condition, or both. These labels characterize conditions that help explain the nature of the relationship between two variables in theoretical statements. For example, a relational statement expressed as a sufficient condition could be: If nurses react with approval of patients’ self-care behaviors (NA), patients increase their efforts in self-care activities (PSC). This is a type of compound statement linking antecedent and consequent variables. The statement does not assert the truth of the antecedent. Rather, the assertion is made that if the antecedent is true, then the consequent is true (Giere, 1979). In addition, no assertion appears in the statement explaining why the antecedent is related to the consequent. In symbolic notation form, the statements may be expressed as:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree