Theory of illness trajectory

Janice Penrod, Lisa Kitko and Gwen McGhan

Carolyn L. Wiener

1930 to present

Marylin J. Dodd

1946 to present

“The uncertainty surrounding a chronic illness like cancer is the uncertainty of life writ large. By listening to those who are tolerating this exaggerated uncertainty, we can learn much about the trajectory of living”

(Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 29).

Credentials and background of the theorists

Carolyn l. Wiener

Carolyn L. Wiener was born in 1930 in San Francisco. She earned her bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary social science from San Francisco State University in 1972. Wiener received her master’s degree in sociology from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) in 1975. She remained at UCSF to pursue her doctorate in sociology, and she completed her Ph.D. in 1978. After receiving her Ph.D., Wiener accepted the position of assistant research sociologist at UCSF, where she remained for her entire professional career, attaining the rank of full professor in 1999.

Photo credit: Robert Foothorap. From (2001). The UCSF School of Nursing Annual Publication, The Science of Caring, 13(1), 7.

Photo credit: Craig Carlson.

Wiener is currently emeritus professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the School of Nursing at UCSF. Her research has focused on organization in health care institutions, chronic illness, and health policy. She has taught qualitative research methods, mentored nursing and sociology students and visiting scholars at UCSF, and conducted numerous seminars and workshops, nationally and internationally, on the grounded theory method.

Throughout her career, Wiener’s excellence earned her several meritorious awards and honors. In 2001, she gave the opening lecture in an international series entitled “Critiquing Health Improvement” at Nottingham University School of Nursing in England. Also in 2001, she was an honoree at the UCSF assemblage “Celebrating Women Faculty,” an inaugural event honoring women faculty for their accomplishments. Wiener’s collaborative relationship with the late Anselm Strauss (co-originator with Barney Glaser of grounded theory) and her prolific experience in grounded theory methods are evidenced by her invited presentations at the Celebration of the Life and Work of Anselm Strauss at UCSF in 1996, at a conference entitled Anselm Strauss, a Theoretician: The Impact of His Thinking on German and European Social Sciences in Magdeburg, Germany in 1999, and at the First Anselm Strauss Research Colloquium at UCSF in 2005. Wiener is highly sought as a methodological consultant to researchers and students from a variety of specialties.

Dissemination of research findings and methodological papers is a hallmark of Wiener’s work. She produced a steady stream of research and theory articles from the mid-1970s. In addition, she authored or coauthored several books (Strauss, Fagerhaugh, Suczek, et al., 1997; Wiener, 1981, 2000; Wiener & Strauss, 1997; Wiener & Wysmans, 1990). Her early works focused on illness trajectories, biographies, and the evolving medical technology scene. From the late 1980s to 1990s, Wiener focused on coping, uncertainty, and accountability in hospitals. Her study examining quality management and redesign efforts in hospitals and the interplay of agencies and hospitals around accountability led to a book, The Elusive Quest (Wiener, 2000). In this book, Wiener describes the poor fit of quality improvement techniques borrowed from corporate industry in a hospital setting where professionals from diverse disciplines provide highly sophisticated care to patients whose individual biographies defy categorization and whose course of illness is idiosyncratic. Wiener challenged the concept that hospital performance can be, or should be, quantitatively measured. All of Wiener’s work is grounded in her methodological expertise and sociological perspective.

Marylin j. Dodd

Marylin J. Dodd was born in 1946 in Vancouver, Canada. She qualified as a registered nurse after studying at Vancouver General Hospital in British Columbia, Canada. She continued her education, earning a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in nursing from the University of Washington in 1971 and 1973, respectively. Dodd worked as an instructor in nursing at the University of Washington following graduation with her master’s degree. By 1977, Dodd returned to academe and completed a Ph.D. in nursing from Wayne State University. She then accepted the position of Assistant Professor at UCSF. During her tenure there, Dodd advanced to the rank of full professor, serving as Director for the Center for Symptom Management at UCSF. In 2003, she was awarded the Sharon A. Lamb Endowed Chair in Symptom Management at the UCSF School of Nursing.

Dodd’s exemplary program of research is focused in oncology nursing, specifically, self-care and symptom management. Her outstanding record of funded research provides evidence of the superiority and significance of her work. She has skillfully woven modest internal and external funding with 23 years of continuous National Institutes of Health funding to advance her research. Her research trajectory has advanced impeccably as she progressively utilized both descriptive studies and intervention studies employing randomized clinical trial methodologies to extend an understanding of complex phenomena in cancer care.

Dodd’s research was designed to test self-care interventions (PRO-SELF Program) to manage the side effects of cancer treatment (mucositis) and symptoms of cancer (fatigue, pain). This research, entitled The PRO-SELF: Pain Control Program—An Effective Approach for Cancer Pain Management, was published in Oncology Nursing Forum (West, Dodd, Paul, et al., 2003). Dodd teaches in the Oncology Nursing Specialty. In 2002, she instituted two new courses (“Biomarkers I and II”) that were developed by the Center for Symptom Management Faculty Group.

Dodd’s illustrious career has merited several prestigious awards. Among these honors, she was recognized as a fellow of the American Academy of Nursing (1986). Her excellence and significant contributions to oncology nursing are evidenced by her having received the Oncology Nursing Society/Schering Excellence in Research Award (1993, 1996), the Best Original Research Paper in Cancer Nursing (1994, 1996), the Oncology Nursing Society Bristol-Myers Distinguished Researcher Career Award (1997), and the Oncology Nursing Society/Chiron Excellence of Scholarship and Consistency of Contribution to the Oncology Nursing Literature Career Award (2000). In 2005, Dodd received the prestigious Episteme Laureate (the Nobel Prize in Nursing) Award from Sigma Theta Tau International. This impressive partial listing of awards demonstrates the magnitude of professional respect and admiration that Dodd has garnered throughout her career.

Dodd’s record in research dissemination is equally illustrious. Her volume of original publications began in 1975. By the early 1980s, she was publishing multiple, focused articles each year, and this pace has only accelerated. She has authored or coauthored 130 data-based peer-reviewed journal articles, seven books and many book chapters, and numerous editorials, conference proceedings, and review papers (1978, 1987, 1988, 1991, 1997, 2001, 2004). Her many presentations at scientific gatherings around the world accentuate this work. Dodd has been an invited speaker throughout North America, Australia, Asia, and Europe.

Dodd’s active service to the university, School of Nursing, Department of Physiological Nursing, and to numerous professional and public organizations and journal review boards augments her outstanding record of service to the profession of nursing. Despite the breadth and volume of these activities, she is an active teacher and mentor. Dodd is the faculty member of record for several graduate courses and carries a significant advising load in the master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral programs at UCSF. From this brief overview of her amazing career, it is clear that Dodd is an exemplar of excellence in nursing scholarship.

Theoretical sources

Although coping with illness has been of interest to social scientists and nursing scholars for decades, Wiener and Dodd clearly explicate that formerly implicit theoretical assumptions have limited the utility of this body of work (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, 2000). Being ill creates a disruption in normal life. Such disruption affects all aspects of life, including physiological functioning, social interactions, and conceptions of self. Coping is the response to such disruption. Because the processes surrounding the disruption of illness are played out in the context of living, coping responses are inherently situated in sociological interactions with others and biographical processes of self. Coping is often described as a compendium of strategies used to manage the disruption, attempts to isolate specific responses to one event that is lived within the complexity of life context, or assigned value labels to the responsive behaviors (e.g., good or bad) that are described collectively as coping. Yet, the complex interplay of physiological disruption, interactions with others, and the construction of biographical conceptions of the self warrants a more sophisticated perspective of coping.

The Theory of Illness Trajectory* addresses these theoretical pitfalls by framing this phenomenon within a sociological perspective that emphasizes the experience of disruption related to illness within the changing contexts of interactional and sociological processes that ultimately influence the person’s response to such disruption. This theoretical approach defines this theory’s contribution to nursing: coping is not a simple stimulus-response phenomenon that can be isolated from the complex context of life. Life is centered in the living body, therefore physiological disruptions of illness permeate other life contexts to create a new way of being, a new sense of self. Responses to the disruptions caused by illness are interwoven into the various contexts encountered in one’s life and the interactions with other players in those life situations.

Within this sociological framework, Wiener and Dodd address serious concerns regarding conceptual overattribution of the role of uncertainty for understanding responses to living with the disruptions of illness (Wiener & Dodd, 1993). An old adage tells us that nothing in life is certain, except death and taxes. Living is fraught with uncertainty, yet illness (especially chronic illness) compounds uncertainty in profound ways. Being chronically ill exaggerates the uncertainties of living for those who are compromised (i.e., by illness) in their capability to respond to these uncertainties. Thus, although the concept of uncertainty provides a useful theoretical lens for understanding the illness trajectory, it cannot be theoretically positioned so as to overshadow conceptually the dynamic context of living with chronic illness.

In other words, the illness trajectory is driven by the illness experience lived within contexts that are inherently uncertain and involve both the self and others. The dynamic flow of life contexts (both biographical and sociological) creates a dynamic flow of uncertainties that take on different forms, meanings, and combinations when living with chronic illness. Thus, tolerating uncertainty is a critical theoretical strand in the Theory of Illness Trajectory.

Use of empirical evidence

The Theory of Illness Trajectory was expanded through a secondary analysis of qualitative data collected during a prospective longitudinal study that examined family coping and self-care during 6 months of chemotherapy treatment. The sample for the larger study included 100 patients and their families. Each patient had been diagnosed with cancer (including breast, lung, colorectal, gynecological, or lymphoma) and was in the process of receiving chemotherapy for initial disease treatment or for recurrence. Subjects in the study designated at least one family member who was willing to participate in the study.

Although both quantitative and qualitative measures were used in data collection for the larger study, this theory was derived through analysis of the qualitative data. Interviews were structured around family coping and were conducted at three points during chemotherapeutic treatment. The patients and the family members were asked to recall the previous month and then discuss the most important problem or challenge with which they had to deal, the degree of distress created by that problem within the family, and their satisfaction with the management of that concern.

Meticulous attention was paid to consistency in data collection: family members were consistent and present for each interview, the interview guide was structured, and the same nurse-interviewer conducted each data collection point for a given family. Audiotaping the interview proceedings, verbatim transcription, and having a nurse-recorder present at each interview to note key phrases as the interview progressed further enhanced methodological rigor. The resultant data set consisted of 300 interviews (three interviews for each of 100 patient-family units) obtained at varied points in the course of chemotherapeutic treatment for cancer.

As the data for the larger study were analyzed, it became apparent to Dodd (principal investigator) that the qualitative interview data held significant insights that could further inform the study. Wiener, a grounded theorist who collaborated with Strauss, one of the method’s founders, was subsequently recruited to conduct secondary analysis of interview data. It should be noted that grounded theory methods typically involve a concurrent, reiterative process of data collection and analysis (Glaser, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1965). As theoretical insights are identified, sampling and subsequent data collection are theoretically driven to flesh out emergent concepts, dimensions, variations, and negative cases. However, in this project, the data had been collected previously using a structured interview guide; thus, this was a secondary analysis of an established data set.

Wiener’s expertise in grounded theory methods permitted the adaptation of grounded theory methods for application to secondary data that proved successful. In essence, the principles undergirding analyses (i.e., the coding paradigm) were applied to the preexisting data set. The analytical inquiry proceeded inductively to reveal the core social-psychological process around which the theory is explicated: tolerating the uncertainty of living with cancer. Dimensions of the uncertainty, management processes, and consequences were further explicated revealing the internal consistency of the theoretical perspective of illness trajectory.

When considering the use of adapted grounded theory methods to analyze preexisting empirical evidence, several insights support the integrity of this work. First, Wiener was well prepared to advance new applications of the method from training and experience as a grounded theorist. The methodological credibility of this researcher supports her extension of a traditional research method into a new application within her disciplinary perspective (sociology). Further support is from the size of the data set: 100 patients and families were interviewed 3 times each, for a total of 300 interviews, a very large data set for a qualitative inquiry. Oberst pointed out that given this volume of data, some semblance of theoretical sampling (within the full data set) would likely be permitted by the researchers (Oberst, 1993). But the sheer size of the data set does not tell the whole story.

Sampling patients who had a relatively wide range of types of cancers (ranging from gynecological cancers to lung cancer) and both patients undergoing initial chemotherapeutic treatment and those receiving treatment for recurrence contributed significantly to variation in the data set. These sampling strategies ultimately contributed to establishing an appropriate sample, especially for revealing a trajectory perspective of change over time. Finally, despite the structured format of the interview, it is important to note that the patients and families dialogued about the previous month’s events in a form of “brainstorming” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 18). This technique allowed the subjects to introduce almost any topic that was of concern to them (regardless of the subsequent structure of the interview). The audiotaping and verbatim transcription of these dialogues contributed to the variation and appropriateness of the resultant data set. Therefore, it may be concluded that empirical evidence culled through the interviews conducted in the larger study provide adequate and appropriate data for a secondary analysis using expertly adapted grounded theory methods.

Major assumptions

Personis the focus of this middle-range theory. Middle range theories address one or more of the paradigm concepts (nursing, person, health, and environment), therefore some are not explicitly addressed; however, the following discussion of theoretical assumptions sheds some light on a theoretical interpretation of these concepts. Wiener and Dodd’s Theory of Illness Trajectory explicates major assumptions that reflect its derivation within a sociological perspective (Wiener & Dodd, 1993). Closer examination of each assumption reveals several related basic premises undergirding the theory.

The Theory of Illness Trajectory encompasses not only the physical components of the disease, but the “total organization of work done over the course of the disease” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 20). An illness trajectory is theoretically distinct from the course of an illness. In this theory, the illness trajectory is not limited to the person who suffers the illness. Rather, the total organization involves the person with the illness, the family, and health care professionals who render care.

Also, notice the use of the term work. “The varied players in the organization have different types of work; however, the patient is the ‘central worker’ in the illness trajectory” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 20). This statement reaffirms an earlier assertion in illness trajectory literature (Fagerhaugh, Strauss, Suczek, et al., 1987; Strauss, Corbin, Fagerhaugh, Glaser, et al., 1984). The work of living with an illness produces certain consequences that permeate the lives of the people involved. In turn, consequences and reciprocal consequences ripple throughout the organization, enmeshing the total organization with the central worker (i.e., the patient) through the trajectory of living with the illness. The relationship among the workers in the trajectory is an attribute that “affects both the management of that course of illness, as well as the fate of the person who is ill” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 20).

Theoretical assertions

The context for the work and the social relationships affecting the work of living with illness in the Theory of Illness Trajectory is based in the seminal work of Corbin and Strauss (1988). As the central worker, actions are undertaken by the person to manage the impact of living with illness within a range of contexts, including the biographical (conception of self) and the sociological (interactions with others). From this perspective, managing disruptions (or coping with uncertainty) involves patient interactions with various players in the organization as well as external sociological conditions. Given the complexity of such interactions across multiple contexts and with the numerous players throughout the illness trajectory, coping is a highly variable and dynamic process.

Originally, it was anticipated that the trajectory of living with cancer had discernible phases or stages that could be identified by major shifts in reported problems, challenges, and activities. This was the rationale for collecting qualitative data at three points during the chemotherapy treatment. In fact, this notion did not hold true: the physical status of the patient with cancer and the social-psychological consequences of illness and treatment were the central themes at all points of measurement across the trajectory.

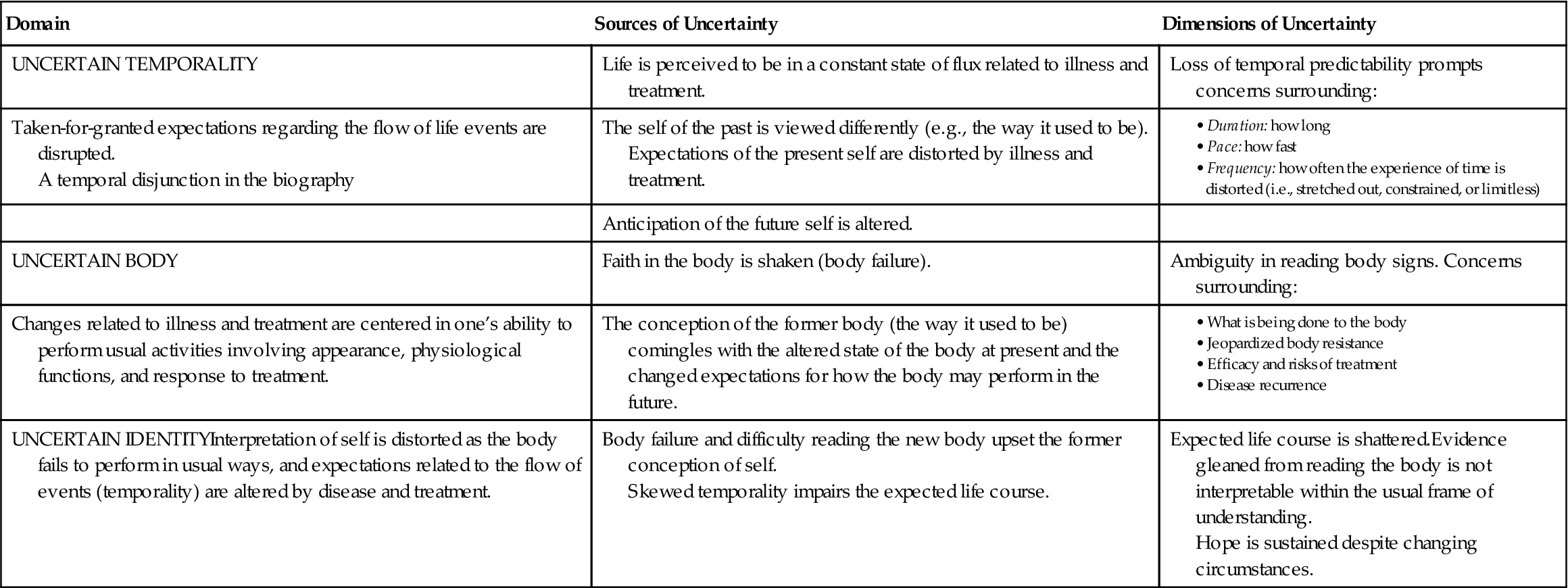

The authors conceptually equate uncertainty with loss of control, described as “the most problematic facet of living with cancer” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 18). This theoretical assertion is reflected further in the identification of the core social-psychological process of living with cancer, “tolerating the uncertainty that permeates the disease” (p. 19). Factors that influenced the degree of uncertainty expressed by the patient and family were based in the theoretical framework of the total organization and external sociological conditions, including the nature of family support, financial resources, and quality of assistance from health care providers.

Logical form

The primary logical form was grounded theory and inductive reasoning. Analytical reading of the interviews provided insights that led to the identification of the core process that unifies the theoretical assertions: tolerating uncertainty. Systematic coding processes were applied to define the dimensions of uncertainty and management processes used to deal with disease. The findings were then examined for fit within extant theoretical writings to extend understanding of the illness trajectory. The resultant qualitatively derived theory was grounded in the reported experiences of the participants and integrated with illness knowledge trajectories to advance the science.

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

The Theory of Illness Trajectory provides a framework for nurses to understanding how cancer patients tolerate uncertainty manifested as a loss of control. Identification of the types of uncertainty is especially useful because it reveals strategies commonly employed by oncology patients in their attempt to manage their lives as normally as possible in the wake of the uncertainty created by a cancer diagnosis. Awareness of the themes of uncertainty and related management strategies faced by patients undergoing chemotherapy and survivorship and their family members has a significant impact on how nurses subsequently intervene with these compromised patient systems who are managing the work of their illness to “facilitate a less troubled trajectory course for some patients and their families” (Wiener & Dodd, 1993, p. 29). An example is Schlairet and colleagues (2010), who examined the needs of cancer survivors receiving care in a cancer community center using the Theory of Illness Trajectory as a framework. They concluded that nurses need to be aware of the specific needs of cancer survivors so that interventions can be developed to meet their needs (Schlairet, Heddon, & Griffis, 2010).

Education

Wiener and Dodd are highly respected educators who share their ongoing work through international conferences, seminars, consultations, graduate thesis advising, and course offerings. Incorporation of this work into these presentations not only advances knowledge related to the utility of illness trajectory models but also, perhaps more importantly, demonstrates how data-based theoretical advancement contributes to an evolving program of research in cancer care (Dodd, 1997, 2001). Including the theory in nursing texts on research and theory exposes researchers to the work and those in nursing practice (Wiener & Dodd, 2000).

Research

The theory has been referenced in a limited number of concept analyses or state-of-the-science papers addressing uncertainty (McCormick, 2002; Mishel, 1997; Parry, 2003). Mishel (1997) has praised the broad theoretical focus maintained through the qualitative approach to theory derivation. Much of the work in coping with illness is constrained by the application of Lazarus and Folkman’s framework of problem-based or emotion-based coping; however, in this study, inductive reasoning produced data-based theory that identifies a broad range of strategies related to tolerating and abating uncertainty (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Mishel, 1997). The variation and range of abatement strategies identified in this theory are a unique and significant contribution to the body of research in coping with the uncertainty of illness.

Further development

In an earlier response article to the original publication, Oberst (1993) took issue with the delimitation of the concept of uncertainty to loss of control. This criticism was echoed by McCormick (2002), who theoretically positioned loss of control in the uncertainty cycle rather than as a manifestation of a state of uncertainty. In their work on end-of-life caregiving, Penrod and colleagues (2012, 2011) posit that minimizing uncertainty by increasing confidence and control is desirable for patients and their family caregivers transitioning through the end-of-life trajectory. Further research into the concept of control is warranted to untangle the conceptual boundaries and linkages between control and uncertainty throughout the illness trajectory.

Other researchers have criticized the implicit assertion that uncertainty (or loss of control) is always a negative event that requires some form of abatement (Oberst, 1993; Parry, 2003). Oberst (1993) suggested the need for further investigation to differentiate work related to tolerating uncertainty from abatement work in order to reveal how effective strategies in each type of work affect the sense of uncertainty throughout the trajectory. Parry (2003) studied survivors of childhood cancer and revealed that although uncertain states may be a problematic stressor for some, a more universal theme of embracing uncertainty toward transformational growth was evident in these survivors.

Penrod (2007) helped to clarify the concept of uncertainty with a phenomenological investigation that advanced the concept of uncertainty and identified different types of uncertainty. The experience of living with uncertainty was dynamic in nature with changes in the types and modes of uncertainty, and various types of uncertainty were guided by the primary tenets of confidence and a sense of control.

These insights demonstrate an evolving body of research related to uncertainty, control, and the illness trajectory. Rather than assume that uncertainty is a negative aspect of life, researchers must remain open to positive transformational outcomes of living through uncertainty. Wiener and Dodd’s original recommendation remains salient, to expand the scope of the illness trajectory framework (Wiener & Dodd, 1993). The illness trajectory theoretical framework is especially useful for understanding the variations in uncertainty and control and for gaining a fuller perspective of the human experience with cancer and other conditions where the significance of uncertainty and control may vary.

Critique

Clarity

One concern in the clarity in Wiener and Dodd’s Theory of Illness Trajectory is the delimitation of the concept of uncertainty to a loss of control. This limited conceptual perspective of uncertainty is clearly set forth in the work; therefore, this issue does not create a significant or fatal flaw in the work. The theory is delineated clearly and well supported by previous work in illness trajectories. Propositional clarity is achieved in the logical presentation of relationships and linkages between concepts. The conceptual derivation of managing illness as work is well developed and provides unique insight into the meaning of living through chemotherapy during cancer treatment. The application of the trajectory model is used consistently to demonstrate the dynamic fluctuations in coping, not in clearly demarcated stages or phases, but in situation-specific contexts of the work of managing illness.

Simplicity

This complex theory is interpreted in a highly accessible manner. The Theory of Illness Trajectory adopts a sociological framework that is applied to a phenomenon of concern to nursing: chemotherapeutic treatment of cancer patients and their families. The sense of understanding imparted by the theory is highly relevant to oncology nursing practice. The theory presents an eloquent and parsimonious interpretation of the complexity of cancer work using key concepts with adequate definition; however, in order to comprehend the theoretical assertions fully, review of previous published studies would be very helpful.

Generality

The authors have limited the scope of this theory to patients and families progressing through chemotherapy for initial treatment or recurrence of cancer. The Theory of Illness Trajectory is well defined within this context. The integration of this middle-range theory with other work in illness trajectories and uncertainty theory indicates an emergent fit with other models of illness trajectories and uncertainty. Further theory-building work may produce a broader scope that permits application of the theoretical propositions in other contexts of illness trajectories.

Accessibility

Grounded theory methods rely on the dominance of inductive reasoning, that is, drawing abstractions or generalities from specific situations. Thus, the derived theory is rooted in the experiences expressed in the hundreds of interviews with cancer patients and their families. The integration of data-based evidence (e.g., quotes) in the formal description of the theory supports the linkages between the theoretical abstractions and empirical observations. Empirical evidence is presented in a logical, consistent manner that rings true to clinical experiences. Thus, the theory is useful to clinicians and holds promise for further research application.

Importance

The importance of the theoretical contributions made by this work, especially types of work and uncertainty abatement strategies during chemotherapy, has been established. The utility of the theory is apparent in cancer treatment, and further theoretical development holds promise of being generalizable to other contexts within cancer care and other illness trajectories. Yet, the limited evidence of directly derived consequences related to application of the Theory of Illness Trajectory in practice-based studies in nursing remains problematic. Applicability of this theory to phenomena of concern to nursing has been established by the focus on cancer chemotherapy. Therefore, potential utility for guiding nursing practice is demonstrated by the integration of the theory into Dodd’s exemplary program of research in cancer care (Dodd & Miaskowski, 2000; Dodd, 2001; 2004; Miaskowski, Dodd, & Lee, 2004; Jansen, Miaskowski, Dodd, et al., 2007).

Summary

Wiener and Dodd’s Theory of Illness Trajectory is at once complex, yet eloquently simple. The sociological perspective of defining the work of managing illness is especially relevant to the context of cancer care. The theory provides a new understanding of how patients and families tolerate uncertainty and work strategically to abate uncertainty through a dynamic flow of illness events, treatment situations, and varied players involved in the organization of care. The theory is pragmatic and relevant to nursing. The merits of this work warrant attention and use of the theory for practice applications that inform nurses as they interpret and facilitate the management of care during illness.