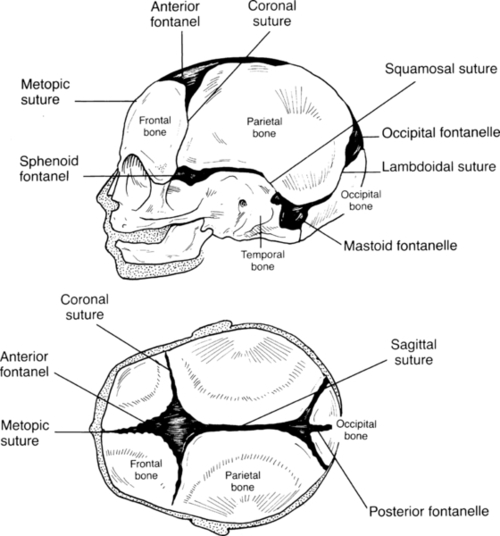

CHAPTER 7 Kathleen Benjamin; Susan Arana Furdon 1. Review key aspects of the perinatal history as it relates to physical assessment of the newborn. 2. Describe methods of determining gestational age (GA). 3. Relate growth pattern and maturity to classification of newborns by GA and weight. 4. Describe a systematic approach in the examination of the newborn infant. A comprehensive newborn physical examination requires a synthesis of perinatal and neonatal risk factors with a systematic approach to the examination. An understanding of growth, maturity, and GA risk factors provides a framework for defining wellness or subsequent problems. The nurse is in a unique position of providing a detailed observation and description within the context of these factors. Elements of a perinatal history focus on the relationship of maternal medical condition and the overall growth and maturity of the infant. Communication from obstetric staff to pediatric staff of fetal anomalies and risk factors for abnormal growth or fetal well-being is essential. 1. Known inherited diseases/conditions: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/geneticdisorders.html. b. Hereditary anemia/coagulation disorders: sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, Von Willebrand’s disease, hemophilia. c. Genetic brain disorder: leukodystrophy, phenylketonuria, Tay–Sachs disease, Wilson’s disease. 2. Chronic disorders or disabilities: diabetes, hypertension, mental retardation, cardiac lesions, renal disease, and seizures. B. Maternal medical history. 2. Chronic illness: diabetes, cardiac disease, hypertension, asthma, thyroid disorder, systemic lupus erythematosus, herpes simplex virus, addiction, and anxiety/depression disorder. 3. Surgical procedures and hospitalizations. 4. Medications before and during pregnancy inclusive of prescribed opiates, medical marijuana/illicit substance use. C. Obstetric history. 2. Previous pregnancies (gravida): number of live born, term versus preterm, spontaneous or elective abortions. 3. Birth weight(s) of live born and neonatal problems identified. 4. Previous fetal demise or neonatal death(s): age of infant and reason for death. D. Social history: early identification of family stressors or support and barriers to teaching. 1. Marital status and consanguinity. 2. Financial support, socioeconomic status, and education level. 3. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use. 4. History of depression. 5. Domestic violence. 6. Religious and cultural considerations. 7. Factors affecting teaching. b. Sensory deficits. E. Pregnancy history. 1. Prenatal care: timing of first visit, compliance with follow-up. 2. Estimated date of confinement. b. Ultrasound dating. c. Birth date calculator (wheel). 3. Single versus multiple gestation. 4. Weight gain and nutritional status. 5. Blood group incompatibility and risk for isoimmunization: maternal blood type and Rh status. a. Antepartum administration of Rho(D) immunoglobulin prophylaxis for D-negative blood group. b. Positive antibody screen (examples: Cc, Ee, Kell, and Duffy). c. Serial fetal surveillance for positive isoimmunization status: antibody titers, ultrasounds, amniocentesis, fetal transfusion. 6. Maternal serum screening: triple or quad screen. 7. Group B streptococcus (GBS) culture at 35 to 37 weeks of gestation. 8. Congenital infection: rubella, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, human papillomavirus, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and parvovirus. Congenital West Nile virus has also been reported (O’Leary et al., 2006). 9. Maternal diabetes. b. Classification. c. Glucose control. 10. Hypertensive disorders. a. Gestational hypertension (formerly called pregnancy-induced hypertension). b. Preeclampsia/eclampsia. c. Chronic hypertension. d. Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP syndrome). 11. Abnormal fetal growth: fundal height, serial ultrasounds. a. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) factors: multiple maternal, placental, uterine, and fetal factors limit intrauterine growth potential (Breeze and Lees, 2007; Lawrence, 2006). (1) Previous small-for-gestational-age (SGA) or IUGR baby. (2) Age greater than 35 or less than 16 years, single marital status, low socioeconomic status. (3) Malnutrition, low pregnancy weight gain, active Crohn’s disease, untreated celiac disease. (4) Unexplained history of miscarriage or stillbirth (fetal loss at >20 weeks of gestation). (5) Multiple gestation. (6) Tobacco exposure. (a) Nicotine releases catecholamines, reduces prostacyclin synthesis. (b) Vasoconstriction and increased vascular resistance decrease placental delivery of nutrients and oxygen. (c) Associated with placental abruption and late fetal death. (d) IUGR rates 3 to 4.5 times those for nonsmokers. (7) Hypertensive/vascular disorders causing placental insufficiency. (a) Chronic hypertension. Incidence 4 times greater, with severe versus mild hypertension. (b) Preeclampsia. (c) Advanced diabetes mellitus. (d) Placental or umbilical cord abnormalities or disruption. (8) Chronic renal failure. (9) Congenital infections: toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpesvirus (TORCH); cytomegalovirus most common association. (10) Congenital malformations and chromosomal abnormalities. b. Large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infant (Lawrence, 2007). (2) Maternal diabetes. (3) Obesity. (4) Previous LGA infant. 12. Fetal anomaly: ultrasound, fetal echocardiography, and amniocentesis. 13. Placental or vascular abnormality: a. Abnormal cord insertion: velamentous. b. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies: reverse end-diastolic flow, increased middle cerebral flow velocity. c. Twin-to-twin transfusion. 14. Amniotic fluid volume: polyhydramnios, oligohydramnios. 15. Recurrent urinary tract infections. F. Labor and delivery. 1. History of presenting problem. a. Labor: preterm labor, post-dates. b. Bleeding. c. Acute abdominal pain. d. Hypertension. e. Medically indicated elective delivery conditions: maternal conditions and/or poor fetal growth/status. f. Trauma. 2. Infection risks: b. GBS: revised Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (Verani et al., 2010). 3. Risk factors that increase neonatal early-onset GBS infection: preterm premature rupture of membranes, prolonged rupture of membranes greater than 18 hours (Baker et al., 2011). 4. Intrapartum chemoprophylaxis for GBS colonization. a. Preterm labor with intact membranes is associated with occult intra-amniotic infection (American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [AAP and ACOG], 2012). 5. Fetal lung maturity. b. Antenatal corticosteroids administered for anticipated preterm delivery at less than 34 weeks of gestation are effective in decreasing neonatal morbidity and mortality (AAP and ACOG, 2012). c. Optimal benefit of glucocorticosteroid: 24 hours after administration for up to 7 days; may be beneficial at less than 24 hours of treatment (Surbek et al., 2012). 6. Spontaneous versus induced labor, indication for induction of labor. 7. Cord prolapse. 8. Fetal distress and nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (Macones et al., 2008). 9. Analgesic and anesthetic prior to and at delivery. 10. Mode of delivery: vaginal, cesarean, assisted (forceps and vacuum); indication for cesarean. 11. Presentation: vertex, breech, brow, chin, and arm. 12. Appearance of amniotic fluid. b. Green: meconium stained. c. Yellow: old meconium, old blood, and sepsis. d. Cloudy: sepsis. 13. Shoulder dystocia (Benjamin, 2005). (1) Maternal risk factors: uterine abnormalities, diabetes, maternal body proportions. (2) Infant risk factors: macrosomia, transverse lie, poor tone, 5-minute Apgar score less than 5. b. Intrapartum events: (1) Mechanical forces of labor alone. (2) Vaginal breech delivery/operative vaginal delivery. (3) Prolonged duration of labor. (4) Precipitous delivery. (5) Prolonged head-to-body interval at delivery. G. Newborn resuscitation (see Chapter 5). The principal basis for use of GA instruments is that fetal maturity follows a predictable, organized course and that physical and neurologic characteristics are common to a given GA. An accurate GA is critical for counseling families and making treatment decisions based on known GA morbidity and mortality risks for a specific GA and birth weight. 1. Use neonatal assessment tools from birth to 5 days, before physical characteristics change. 2. Perform within 48 hours of birth for highest accuracy. 3. Consider problems with accuracy of GA assessments when using GA-based treatment guidelines for extremely preterm treatment or withdrawal-of-care decisions (Parikh et al., 2010). 4. Neurologic findings may be influenced by prematurity and disease processes. B. Most common tools. 1. Dubowitz: clinical assessment of GA (Dubowitz et al., 1970). a. Scores criteria: 10 neurologic and 11 external (physical). b. Combined total score correlated to weeks of gestation. c. Combined score has higher correlation (±2 weeks, 95% confidence) than either component separately. d. SGA infants: external signs underscored and neurologic signs overscored; combined score reliable. e. Overestimates GA in premature infants. f. Widely used before development of Ballard score. 2. Ballard: newborn maturity rating. a. Simplified system based on Dubowitz’s method, less time to use. b. Eliminates active tone scoring, passive tone more useful than active tone. c. Six neurologic and six physical criteria, scores totaled. d. GA maturity rating assigned using form chart. 3. New Ballard Score (Ballard et al., 1991). a. Modified to assess GA of 20 to 44 weeks. b. Accurate within 2 weeks of gestation; sick or well infants. c. For 20 to 26 weeks of gestation: most accurate when scored within first 12 hours of life. d. Limitations. (1) Examination should be done twice by two different examiners for objectivity. (2) Infant must be in a quiet, alert state. (3) Scoring affected by: (a) Breech and positional deformities, (b) Neurologic disorders and asphyxia, and (c) Infants affected by maternal medications. 4. Eye examination: anterior vascular lens capsule evaluation (Fig. 7-1). b. Limitations: requires direct ophthalmoscopic exam, cannot be used at less than 27 weeks of gestation, and must be done in first 24 to 48 hours of life. Not used routinely. C. GA examination technique: Use published New Ballard chart for scoring each criterion. 1. Neurologic criteria features. (1) Evaluates degree of arm and leg flexion and extension and leg abduction. (2) Flexion and hip adduction increase with increasing GA. (3) Early in gestation, the infant’s resting posture is hypotonic. (4) Observe infant’s posture while supine and quiet. b. Square window. (1) Evaluates flexion when the wrist is at a right angle to the forearm. (2) Angle decreases with increasing GA because of the influence of maternal hormones at the end of pregnancy. (3) Findings do not change after birth. (4) Flex infant’s hand on the forearm between examiner’s thumb and index finger. Use sufficient pressure to get full flexion. Visually measure angle between hypothenar eminence and ventral aspect of forearm. c. Arm recoil. (1) Evaluates degree of arm flexion and the strength of recoil. (2) Place infant supine, flex arms for 5 seconds, then fully extend arms by pulling the hands downward, then release. d. Popliteal angle. (1) The angle decreases with increasing GA. (2) Position infant supine, pelvis flat on surface; hold thigh in knee–chest position with left index finger and thumb. Place right index finger behind infant’s ankle and extend leg with gentle pressure. (3) Measure the angle between the lower leg and thigh, posterior to the knee. e. Scarf sign. (2) Observe the position of the elbow relative to the midline of the infant’s body. f. Heel to ear. (2) Observe distance between the foot and head and the degree of knee extension. Knee is left free and may draw down alongside abdomen. 2. Physical examination criteria: observe and grade according to Figure 7-2. (1) With increasing GA, transparency decreases and more texture develops, vessels become obscured. (2) As gestation progresses beyond 38 weeks, subcutaneous tissue decreases, causing wrinkling and desquamation. b. Lanugo. (1) Fine, downy hair that covers the body of the fetus from 20 to 28 weeks. (2) At 28 weeks, it begins to disappear around the face and anterior aspect of the trunk. (3) At term, a few patches may be present over the shoulders. c. Plantar creases. (2) An infant with IUGR and early loss of vernix caseosa may have more plantar creases than expected for size. (3) After 12 hours, the skin begins to dry and plantar creases are no longer a valid indicator of GA. d. Breast development. (1) Nipple size and amount of breast tissue are examined. (2) A 1- to 2-mm nodule of breast tissue is palpable by about 36 weeks and grows to approximately 10 mm by 40 weeks of gestation. e. Eyes and ears. (1) Evaluate for fused eyelids. (2) At 26 to 28 weeks of gestation, fused eyelids open. (3) Assess ear formation and amount of pinna cartilage. (4) Inward curving of the upper pinna usually begins by 34 weeks of gestation and by 40 weeks extends to the lobe. (5) Before 34 weeks, the pinna has little cartilage and will stay folded on itself. (6) By 36 weeks there is some cartilage, and the pinna will spring back from being folded. f. Genitalia. (a) Early in gestation the clitoris is prominent, with small, widely separated labia. (b) By 40 weeks, fat deposits have increased in size in the labia majora, so that the labia majora completely cover the labia minora. (2) Male infant: evaluate presence of testes, degree of descent into scrotum, and development of rugae on the scrotum. (a) The testes begin to descend from the abdomen at 28 weeks. (b) At 37 weeks, the testes can be palpated high in the scrotum. (c) At 40 weeks, the testes are completely descended and scrotum is covered with rugae. (d) As gestation progresses, the scrotum becomes more pendulous. D. Clinical estimate of GA (AAP, 2004; AAP and ACOG, 2012). 1. Document GA on all newborns. 2. Use standard terminology. a. GA is the time between the last menstrual period and the day of delivery. b. Use obstetric estimated GA when the physical exam approximates the GA by estimated date of confinement within 2 weeks (Thilo and Rosenberg, 2012). c. Express in completed weeks of gestation. 3. Document marked discrepancy between obstetric and physical data. 4. Assign GA using assessment of all obstetric, pediatric, and nursing data (AAP and ACOG, 2012). 5. Classify maturity. a. Preterm: infant born on or before the end of the 37th week of gestation. (1) Subcategory: “late preterm” defined as between 340/7 and 366/7 weeks of gestation (Engle, 2006). (2) Replaces the phrase near term, emphasizes the higher morbidity and mortality of premature infants. b. Term: infant born from the first day of the 38th week to the last day of the 42nd week. c. Post-term: infant delivered from the first day of the 43rd week. The intrauterine growth pattern reflects fetal well-being. This pattern is influenced by race, maternal health or disease, placental function, medications, socioeconomic factors, nutrition, altitude, substance abuse, and smoking. There are multiple reasons to classify growth and maturity of the newborn infant: ■ Assist in identification of the most commonly occurring problems in the newborn period. ■ Estimate dating if there is no prenatal care. ■ Examine discrepancy between weight and GA. ■ Standardize reports of health statistics. 2. Growth curves should be GA- and gender-specific for weight, length, and head circumference. B. Obtain measurements. a. Normal-appearing infants: weight, length, and head circumference. b. Dysmorphic appearance: may require more extensive measurements. 2. Birth weight. a. Obtain as soon as possible after delivery. b. Express in grams. c. Weigh unclothed infant when quiet (weight can be falsely increased with significant motion). d. Classifications (regardless of GA) (AAP and ACOG, 2012). (1) Low birth weight: less than 2500 g birth weight. (2) Very low birth weight: less than 1500 g birth weight. (3) Extremely low birth weight: less than 1000 g birth weight. 3. Length: crown-to-heel measurement. a. Most variable measurement: requires full extension of normally flexed infant. b. Measure length with infant supine and leg extended, head to heel. c. Accuracy facilitated by use of measurement board. d. Use crown-to-rump measurement to establish proportionality when length falls below norms (referenced data in Smith’s Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation [Jones, 2006]). (1) Congenital bone disorders. (2) When lower extremity anomalies make crown-to-heel measurement unreliable. 4. Head circumference (HC): indication of normal brain growth. a. Measurement of largest occipitofrontal circumference. b. Apply paper measurement tape firmly around head above the eyebrow ridges, from most prominent frontal to occipital areas. c. Occipitofrontal circumference as measured may be erroneous: significant cranial molding, craniosynostosis, caput succedaneum, and cephalohematoma need to be noted along with the measurement. d. Consider parent head size versus intracranial pathology when head size is of concern. C. Plot newborn’s weight, length, and head circumference by GA on standardized growth charts. 1. CDC national reference for term infants. a. Recommend use of World Health Organization growth charts for ages 0 to 24 months (Grummer-Strawn et al., 2010). b. Growth below the 2nd percentile and above the 97th percentile indicates growth 2 standard deviations from median and should be investigated. c. Available at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts. 2. Colorado Intrauterine Growth Chart (Fig. 7-3) (Lowdermilk and Perry, 2007). a. Colorado growth charts developed in 1960s. b. Other limitations of Lubchenco data (Thomas et al., 2000). (2) Overestimates number of infants greater than 90th percentile and less than 10th percentile. (3) Population sampled only whites and primarily low socioeconomic groups. c. Leads to inaccurate classification of SGA and LGA. 3. Babson and Benda fetal–infant growth graph (Fenton, 2003). b. CDC growth charts could be used after 50 weeks. c. Original 1976 chart updated in 2003 with growth data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. d. Useful in neonatal intensive care units as it reflects preterm infants’ postnatal weight and length delay in comparison to head growth. e. Open access with credit given, available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/3/13. 4. Pediatrix Medical Group Inc. Growth Chart (Thomas et al., 2000) (Fig. 7-4). a. GA had largest influence on each growth parameter. b. Infants less than 30 weeks of GA: overall lower growth parameters compared to Lubchenco chart. c. Infants greater than 36 weeks of GA: larger and heavier. d. Updated intrauterine growth curves using large, racially and geographically diverse sample from Pediatrix Medical Group NICU’s (Olsen et al., 2010). D. Compare weight with GA to determine size classification (weight compared with established norm). 1. SGA: birth weight less than 10th percentile. 2. Appropriate for gestational age (AGA): birth weight within 10th and 90th percentiles. 3. LGA: birth weight greater than 90th percentile. E. Compare all growth parameters (head circumference, birth weight, and length) with GA. a. Process of slowing of intrauterine growth rate. b. IUGR infants may or may not be SGA. c. Below expected norms for weight and length at birth based on GA, race, and gender. 2. Classifications. (1) Proportional decreased growth. (2) Measurements for weight, length, and HC all within the same growth curve, all less than 10th percentile. (3) Etiology: decreased growth potential or reduced fetal cells (see Pregnancy History). (a) Intrauterine congenital infection. (b) Congenital malformation. (c) Chromosomal disorder. b. Asymmetrical (head-sparing). (1) Disproportionate reduction in weight and length at birth compared with head circumference. (2) Weight below expected norms for GA, race, and gender. (3) Etiology: normal number of cells; reduced cell size. (a) Uteroplacental insufficiency. (b) Maternal malnutrition. (c) Extrinsic factors occurring late in pregnancy. F. Determine neonatal mortality risk based on classification of newborns by standardized birth weight norms and GA. 1. Morbidity and mortality statistics: standardized reporting of reproductive health statistics. 2. Establishment of level of risk for short- and long-term complications. 3. Mortality risk (Fig. 7-5). 4. Morbidity risk by birth weight and GA (Fig. 7-6). G. Identify infants at risk for respiratory disease, hypoglycemia, and thermal instability based on classification(s): 2. Late preterm (Engle, 2006; McIntire and Leveno, 2008). b. GA ≥34 and less than 37 weeks. c. Potential problems: temperature instability, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, apnea, bradycardia, feeding difficulty, and hyperbilirubinemia. 3. Post-term: problems associated with placental insufficiency—asphyxia and meconium aspiration. 4. IUGR (Doctor et al., 2001; Rosenberg, 2008). a. Focus initial exam on identification of congenital anomalies and dysmorphic features. b. Associated with chromosomal syndromes, intrauterine drug exposure, and viral infections. c. Typical appearance of asymmetrically growth-restricted infant. (1) Head disproportionately large for trunk. (2) Extremities appear wasted. (3) Facial appearance of “old man.” (4) Large anterior fontanelles with cranial sutures wide or overlapping. (5) Thin umbilical cord, diminished Wharton’s jelly. (6) Scaphoid abdomen. (7) Skin: petechiae, loose, decreased subcutaneous fat, dry, flaky, little or no vernix caseosa. (8) Tone and alertness dependent on degree of IUGR. (a) Mild/moderate IUGR: hyperalert, jittery, hypertonic. (b) Severe: hypotonic, “apathetic.” d. Potential problem list; increased risk at all GAs with IUGR. (2) Hypothermia: high demand plus inadequate adipose tissue to maintain temperature. (3) Polycythemia/hyperviscosity: increased red blood cell production in utero caused by chronic hypoxia or endocrine/metabolic or chromosomal disorder. (4) Hypoxia: birth asphyxia, persistent pulmonary hypertension, and meconium aspiration. (5) Infection. (6) Problems related to etiology of growth restriction. (7) Long-term morbidity and mortality dependent on etiology: 10 to 20 times perimortality of AGA infants. 5. LGA infant. (2) Infant of diabetic mother. (b) Characteristic large body with head circumference within normal limits for GA (insulin does not cross the blood–brain barrier). b. Potential problem list (Lawrence, 2007). (1) Abnormal glucose metabolism after birth, hyperinsulinemia, and hypoglycemia. (2) Birth trauma from difficult extraction (fractured clavicle, brachial plexus injury) or asphyxia. (3) Complications from operative or assisted delivery: respiratory distress, adverse effects of anesthesia. (4) Iatrogenic prematurity: overestimation of fetal GA. (5) Association with other problems related to infant of diabetic mother: respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, polycythemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and congenital anomalies. (6) Pulmonary hypertension. (7) Poor feeding. (8) Thermal instability as a result of central nervous system (CNS) trauma or infection. (9) Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, LGA, macroglossia, hypoglycemia, umbilical hernia, undescended testes. A systematic approach to the physical examination of the newborn should be performed in the first 12 to 18 hours of life after successfully transitioning. This prevents pertinent omissions and provides a detailed description that can be utilized in communication of alterations in anatomic structure or changes in physiology or function. These observations ultimately must be made within the context of the patient’s history and GA. Communication to the primary care provider is essential for further evaluation and prompt treatment. 1. Examine in well-lit room; direct light should not be in infant’s face. 2. Warm hands and equipment. 3. Keep infant warm by using overhead heat source or uncovering small areas at a time to prevent hypothermia. 4. Complete detailed observations prior to physical contact. 5. Order of examination: a. Depends on the purpose of the examination and the current state of the infant (Fletcher, 1998). b. Generally: least invasive observations to most disturbing techniques. c. Observe skin throughout the examination. d. Evaluate neurobehavior within the context of the infant’s behavioral state. 6. Document physical examination in patient care record inclusive of description of abnormalities and vital signs. B. Timing of examinations (AAP and ACOG, 2012). 1. Recognize life-threatening symptoms and address those prior to a comprehensive examination. 2. Modify elements of examination based on infant’s state or illness. a. Initial examination in delivery room. b. Apgar scoring. c. Inspection for birth injury or major congenital malformation. d. Evaluation of pulmonary and cardiovascular adjustment to extrauterine life. e. Notification of primary care provider. (2) Maternal fever. (3) Abnormal examination findings. (4) Evidence of and/or suspected substance abuse. 3. Comprehensive newborn examination. b. Discharge examination: focus on problem(s) during hospitalization, problems with feeding and weight gain, and ability of parent(s) to meet infant’s needs. C. General appearance: initial impression. 1. State: indicator of well-being. a. Sleep states: deep sleep and light sleep. b. Awake states: quiet alert, actively alert, and crying. 2. Color. b. Lighting and color of blankets can affect perception of color. c. Central cyanosis; always abnormal. (1) Recognition influenced by hematocrit, temperature, and environmental factors. (2) Central cyanosis: superficial capillaries exceed 5 g/dL unsaturated hemoglobin (Park, 2008). (3) Variety of etiologies: cardiac, pulmonary, infection, metabolic, neurologic, and hematologic. d. Acrocyanosis. (1) Suggests instability of peripheral circulation. (2) Cyanosis limited to hands, feet, and circumoral area (lips). (3) May be a result of cold, stress, shock, and polycythemia. (4) Normal finding for 24 to 48 hours after birth. e. Pallor: pale, white appearance. (1) Reflects poor perfusion and circulatory failure or acidosis. (2) With bradycardia, indicates anoxia or vasoconstriction found in shock, sepsis, or severe respiratory distress. (3) With tachycardia, can indicate anemia. f. Plethora: ruddy or red appearance. (1) May indicate polycythemia. g. Jaundice: yellow pigmentation in skin or conjunctivae due to deposition of bilirubin. (1) Abnormal in the first 24 hours of life. Needs immediate investigation. (2) Cephalocaudal progression. h. Mottling: checkerboard red-and-white pattern. (2) May be seen in cold stress, hypovolemia, and sepsis. (3) Cutis marmorata: exaggerated marbling greatest on extremities but also present on trunk (Fletcher, 1998). i. Harlequin sign: distinct midline demarcation. (1) Pale on one side and red on the opposite side. (2) Owing to immature autoregulation of blood flow. 3. Respiratory effort. (1) Normal 40 to 60 respirations per minute. (2) Rate can vary with activity of infant. b. Quality: absence of “work of breathing.” (1) Retractions: occur more often in premature infant as a result of highly compliant chest wall. (2) Nasal flaring: diameter of nares increased as mechanism to decrease airway resistance. (3) Expiratory grunting: increase in intrathoracic pressure to prevent volume loss during expiration as a result of alveolar collapse. 4. Wheezing: due to increased airway resistance. High-pitched rhonchi heard more loudly on expiration. 5. Stridor: partially obstructed airway. 6. Nutritional status. a. Well nourished: increased subcutaneous fat, without loose skin. b. Growth restricted: thin and wasted appearance, no subcutaneous fat, loose skin. 7. Tone. b. Initial position reflects intrauterine position and may reflect limitation of movement or increased pressure on head, trunk, or extremities. c. Degree of flexion and amount of resistance demonstrated with examiner’s extension of extremities. d. Decreased flexion (hypotonia) or increased flexion (hypertonia) should be evaluated further. 8. Congenital defects. b. Describe anatomic structures fully: size, number, shape, position, color, texture, continuity, and alignment. 9. Temperature (see Chapter 6). D. Skin (see Chapter 36). a. Findings differ with GA, especially with extremely low birth weight. b. Indicators of underlying illness: petechiae, pigmentation, rashes, and pustules. c. Congenital lesions may not be apparent at birth; influenced by maternal hormones. d. Differentiate between findings at birth versus injury after birth (medical interventions). e. Use basic descriptors: color, quantity, size, shape, pattern of distribution, and texture. 2. Skin is soft, smooth, and opaque and should be warm to the touch; cold, clammy skin may indicate shock. 3. Inspect lesions, rashes, bruises, and birthmarks. Differentiate between benign findings and those suspicious of infection or hematologic or neurologic disturbance. 4. Palpate for texture (raised, flat) unless lesion is open. 5. Vernix caseosa. b. Sebaceous gland secretions and exfoliated skin cells. c. Presents during third trimester and decreases with increasing GA. 6. Lanugo: fine soft hair covering face, trunk. a. Amount and distribution are GA dependent. b. Covers entire body in preterm, disappears at 32 to 37 weeks from face and lower back. c. At term, present on upper back and limbs. 7. Erythema toxicum (newborn rash). a. Erythematous macules, each containing a central papule (yellow or white). b. Papules contain eosinophils in a fluid that is sterile. c. Persist for several days and then resolve spontaneously. d. Most often located on trunk, arms, and perineal areas. e. Never located on soles of feet or palms of hands. 8. Pustular melanosis. a. Benign, transient, nonerythematous pustules and vesicles. b. Single or clusters, rupture leaves scaly white lesion. 9. Ecchymosis: nonblanching blue or black area. a. Extravasation of blood into tissue. b. Related to trauma of blood vessels. 10. Petechiae. a. Tiny red or purple nonblanching pinpoint macules. b. Benign when found on presenting part; result from areas of compression during delivery. c. More diffuse distribution suggests general thrombocytopenia. d. Require further evaluation when progressive. 11. Vascular nevi. a. Common cutaneous malformation(s) that can occur anywhere on body. b. May present at birth or may develop in early infancy. c. Types. (1) Nevus simplex or capillary hemangiomas (stork bite). (a) Macular patches with diffuse borders. (b) Found on forehead, nape of neck, glabella, and eyelids. (c) Blanch when pressure is applied. (d) Resolve spontaneously. (2) Nevus flammeus (port wine stain). (a) Flat, sharply defined lesion. (b) Most common on back of neck. (c) If present over the face following branches of trigeminal nerve (forehead and upper eyelid), may be associated with Sturge–Weber syndrome. (d) Will not blanch with pressure. (e) May fade with time but will not resolve. 12. Café-au-lait spots. a. Light tan or brown macules with well-defined borders. b. Deeper pigmentation than surrounding skin. c. Six or more may be pathologic. 13. Strawberry hemangioma(s). a. Red, raised, circumscribed, and compressible. b. Can occur anywhere on the body. c. Proliferate: increase in size and number. d. Most involute spontaneously. e. No treatment is required unless they affect vital function. f. Occur with increasing frequency with decreased GA. 14. Epidermolysis bullosa. a. Blistering internally and externally. b. May be either autosomal dominant or recessive. 15. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. a. Skin response to Staphylococcus aureus. b. Scalded skin appearance. 16. Sucking blisters: skin erosion on thumbs, index fingers, wrist, or forearm from intrauterine sucking. E. Head. a. Up to 90% of the congenital malformations present at birth are apparent on the head and neck (Jones, 2006). b. Review perinatal history, abnormal ultrasound findings, and mode of delivery. c. Many variations are transient or racial, sexual, or familial traits. 2. Obtain head circumference (HC measurements). a. Measurement reflects brain growth. b. Predictable measurement: follows norms for GA and weight. c. Usually HC falls on same percentile curve as length. Determine etiology of abnormal growth if length and HC differ by greater than one quartile. d. Normal HC 32 to 38 cm for full-term AGA. (1) Microcephalic: poor brain growth, atrophy, or premature cranial synostosis. (2) Macrocephalic: familial (follows persistently higher but consistent growth curve) and pathologic (hydrocephalus: increase in cerebrospinal fluid results in increasing HC). 3. Observe shape and symmetry; may reflect effect of birth process or in utero position or significant anatomic defect. (2) Elongation of head with prominence of occiput and overriding sagittal suture line. (3) Resolution in first week of life. (4) Not uncommon for overriding sutures to persist longer than 1 week in the extremely low birth weight infant. b. Rounded head occurs with delivery by cesarean section without labor; flat head with increased occipital–frontal diameter occurs with breech delivery. c. Abnormal prominence, depressions, or flattening. d. Abnormal shape of skull. (1) Plagiocephaly: asymmetrical appearance of head, flattened on one side. (2) Craniosynostosis: premature closing of one or more of cranial sutures. (3) Anencephaly: failed closure of neural tube without skull formation. 4. Palpate sutures and fontanelles (Fig. 7-7). (2) Overriding. (b) Fused suture: premature synostosis. (3) Wide sutures. (a) May be wide in the absence of increased intracranial pressure. (b) Widened lambdoid suture: indicates increased pressure. (c) Sagittal and metopic sutures normally wider in black infants (Fletcher, 1998). (4) Craniotabes: soft demineralized area typically found in parietal and occipital regions along the lambdoidal suture line. (a) Under gentle pressure, the area will collapse and then recoil. (b) Infant engaged in the vertex position for a prolonged period. (c) Pressure of skull against maternal pelvis results in delayed ossification or reabsorption of bone. b. Anterior fontanelle. (1) Location: junction of sagittal and coronal sutures. (2) Shape: diamond. (3) Size: measures 4 to 6 cm at the largest diameter (bone to bone). (4) Normally closes at 18 months. c. Posterior fontanelle. (1) Location: junction of lambdoidal and sagittal sutures. (2) Shape: triangular. (3) Size: usually fingertip. (4) Normally closes by 2 months of age. d. Abnormal findings. (2) Size: large fontanelle, considerable racial variations; not pathognomonic for any condition (Fletcher, 1998). (3) Closed fontanelles with immobile, rigid sutures suggest premature synostosis. (4) Bruit over temporal, frontal, or occipital area associated with high-output cardiac failure and arteriovenous malformation. (5) Abnormal tension. (b) Depressed fontanelle: associated with dehydration.

Physical Assessment

PERINATAL HISTORY (SEE CHAPTERS 1, 2, 3, AND 4)

GESTATIONAL-AGE INSTRUMENTS

CLASSIFICATION OF GROWTH AND MATURITY

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

7: Physical Assessment

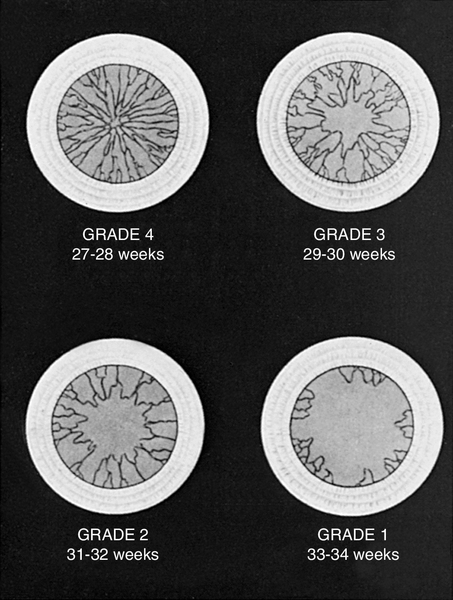

FIGURE 7-1 ■ Grading system for assessment of gestational age by examination of anterior vascular capsule of lens. (From Hittner, H.M., Hirsch, N.J., and Rudolph, A.J.: Assessment of gestational age by examination of the anterior vascular capsule of the lens. Journal of Pediatrics, 91[3]:455-458, 1977.)

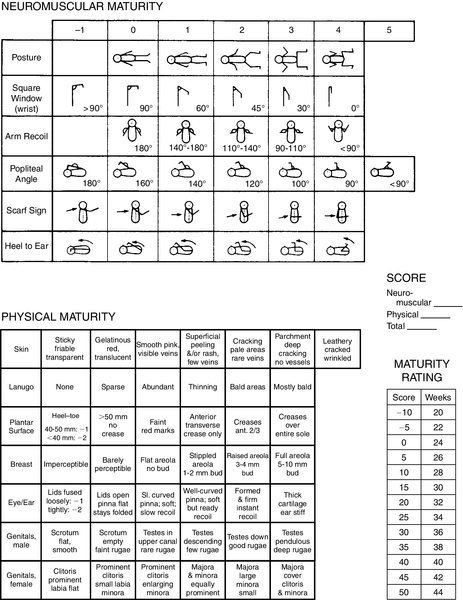

FIGURE 7-2 ■ New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. (From Ballard, J.L., Khoury, J.C., Wedig, K., et al.: New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. Journal of Pediatrics, 119[3]:417-423, 1991.)

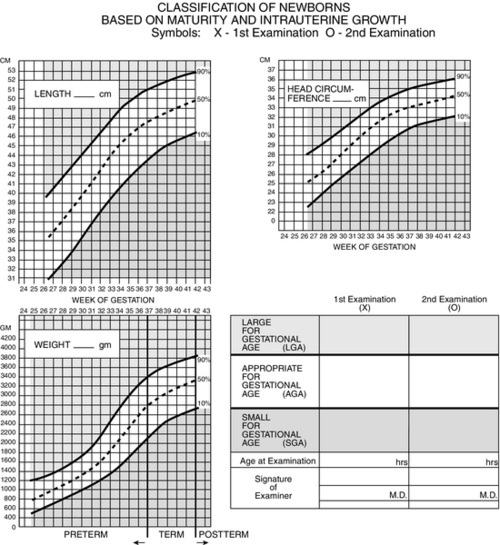

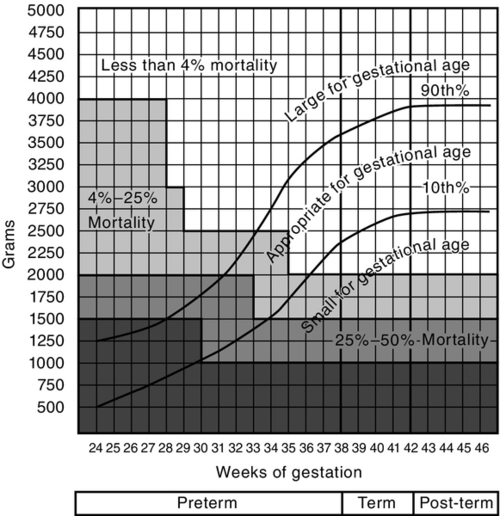

FIGURE 7-3 ■ Estimating gestational age: Newborn classification based on maturity and intrauterine growth. (From Lowdermilk, D.L. and Perry, S.E.: Maternity & women’s health care [9th ed.]. St. Louis, 2007, Elsevier Mosby; modified from Lubchenco, L., Hansman, C., Boyd, E.: Intrauterine growth in length and head circumference as estimated from live births at gestational ages from 26 to 42 weeks. Journal of Pediatrics, 37:403, 1966; Battaglia, F. and Lubchenco, L.: A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. Journal of Pediatrics, 71[2]:159-163, 1967.)

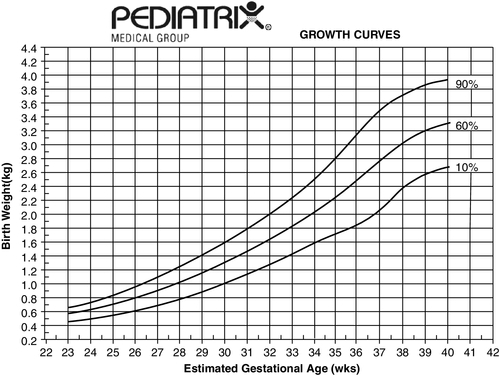

FIGURE 7-4 ■ These growth curves represent an estimate of intrauterine growth based on data from 80,011 neonates admitted to 114 neonatal intensive care units (birth weight above 250 g and gestational age of 22 to 42 weeks). Gender, race, and multiple births had a small but significant effect on each parameter (see the Clinical Research Center at Pediatrix U, www.pediatrixu.com/clinical_research_center.asp). These curves are a reference for the clinician to assess neonates’ intrauterine and postnatal growth. The CDC national references (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/) may also be used for term infants. (Copyright 2001 Pediatrix Medical Group, Inc. Reproduction of this material by any means without the express written permission of Pediatrix Medical Group, Inc., is prohibited. Please see www.pediatrix.com for updated information.)

FIGURE 7-5 ■ University of Colorado Medical Center classification of newborns by birth weight and gestational age and by neonatal mortality risk. (From Battaglia, F. and Lubchenco, L.: A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age. Journal of Pediatrics, 71[2]:159-163, 1967.)

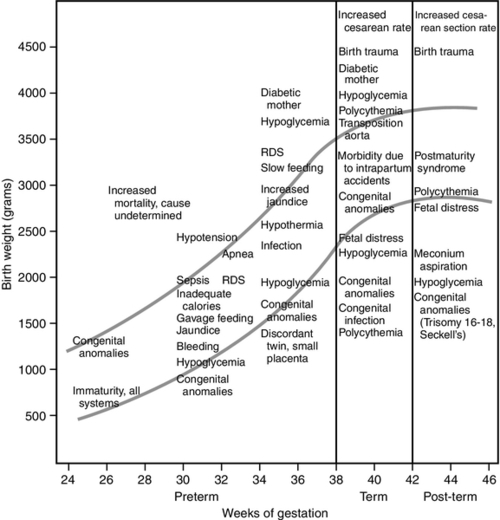

FIGURE 7-6 ■ Specific neonatal morbidity by birth weight and gestational age. RDS, respiratory distress syndrome. (From Lubchenco, L.O.: The high-risk infant. Philadelphia, 1976, W.B. Saunders.)

FIGURE 7-7 ■ Two views of skull, showing fontanelles and sutures.