CHAPTER 7. Clinician and Patient Safety

Sherri Barnhill, MA, RN∗

Introduction, 95

Barriers to Improvement, 95

Pathophysiology of Error, 96

Patient Safety, 98

Organizations, 103

Summary, 107

In today’s complex world of health care, clinician and patient safety is paramount now more than ever. Most health care organizations have dedicated staff whose job it is to improve safety for their employees as well as their patients. There are many professional groups that have formed in recent years to support the patient safety teams in hospitals to design safer practices. In this chapter, the following information will be provided: reasons why errors occur in the health care setting, barriers to improving safety, the pathophysiology of errors, and ways to improve patient safety in an organization, with specific examples included for infusion nurses. The last section of the chapter is dedicated to regulatory, accrediting, and professional organizations that are looking at clinician and patient safety from a higher level. Their perspectives on the topic and the ways that they desire adherence or expect compliance are outlined. As each organization approaches clinician and patient safety from a different perspective, the lessons received from each will provide a broad base in which to practice safety in any health care setting.

INTRODUCTION

The purposeful study of improving the safety of both clinician and patient intensified after the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System was published in 2000. The IOM estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 lives are lost each year through medical errors, of which 7000 are from medication errors (IOM, 2000). In patient safety circles, that number is routinely quoted. However, to help put these numbers in perspective, consider that many towns across the United States have far fewer residents. Medical errors are the eighth leading cause of death in the United States. More people die from medical errors than acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), motor vehicle deaths, or breast cancer (IOM, 2000). Where does one start to tackle this huge problem in a health care environment that continues to grow in complexity every day? First of all, there is a need to grasp why errors occur in the first place in order to identify ways to prevent them.

BARRIERS TO IMPROVEMENT

No clinician, be it a physician, nurse, or other health care provider, drives to work each morning and ponders, “How can I mess up today?” On the contrary, clinicians from all specialties arrive at their health care organizations ready to meet the complex demands of caring for their patients every day. So what are their barriers? They fall into three categories: lack of awareness, complex environment, and culture of blame.

LACK OF AWARENESS

The first barrier is a lack of awareness. This refers to lack of awareness of the magnitude of the problem. (This barrier is not referring to lack of clinical knowledge.) Although there are between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths annually, there are approximately 2.5 million nurses and 900,000 physicians practicing in 7500 hospitals across the United States (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and U.S. Census Bureau,). Given these figures, a clinician would, statistically speaking, rarely be involved in a serious incident. Therefore it is not uncommon for nurses and physicians to believe that provision of health care is safer than it actually is in the day-to-day world.

COMPLEX ENVIRONMENT

The second barrier to safety improvement involves the complex environment in which health care providers work. Until fairly recently nurses worked without the benefit of computerized axial tomography (CAT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs). No one knew that one day a gallbladder could be removed through a laparoscope or that a diseased heart could be repaired without using a heart bypass machine. Neonatal intensive care units several years ago could not imagine successfully caring for infants weighing 1 pound. However, along with the tremendous life-giving benefits of technology has come the stress of harnessing that knowledge and making the right decision each and every time. The problem is that clinicians, no matter how well educated, are human and mistakes are going to happen. Vigilance will not prevent human error. Health care is so complex that no one can predict all the possible complications that can occur when providing care to a patient. Therefore because events are tightly interlinked, when an error occurs downward spiraling events develop in rapid succession.

Consider, for example, an infusion nurse who is asked to assist a nurse on a medical-surgical floor who is unable to obtain a peripheral line in one of her patients. The medical-surgical nurse provides the infusion nurse what she believes is the necessary information. The infusion nurse prioritizes care based on the information provided and arrives on the unit within 30 minutes to provide assistance. What the infusion nurse sees, however, is incongruent with the message that was received from the patient’s nurse. The infusion nurse arrives to find a room full of health care personnel quickly trying to manage a patient who is hemodynamically compromised and is being closely monitored. One nurse’s lack of communication dominoes into a scenario in which the patient’s survival can be at risk.

In all work environments, there are two basic kinds of errors that people make. James Reason (2000), a British professor of psychology, defined them as either active errors or latent errors. Active errors, also known as “errors at the sharp end of health care,” occur at the point of interaction between the person (for example, a nurse) and a larger system (for example, a medication cart). An example of an active error is the nurse pulling the wrong medication out of the drawer and administering it. Active errors are considered to occur on the frontline of the job and are in direct control of the clinician on the sharp end of health care. In this example, it would be at the bedside where the medication was given to the patient.

The second type of error is called a latent error. Latent errors are also known as “errors at the blunt end of healthcare.” This is an error that contributed to or gave rise to the active error and is not necessarily apparent when it happens. In the preceding example, the latent error might have been that the incorrect medication was either a look-alike or sound-alike medication. Practicing in a hectic chaotic environment, the nurse mistakes the look-alike medication for the intended medication. Initial review of the incident often focuses on the active error and the nurse on the sharp end at the bedside often gets blamed for the mistake. When that occurs, no attention is focused on the latent error, increasing the likelihood that the error will be repeated. Only when it is recognized that the latent error is actually the root cause of the error that needs to be fixed will the medical errors be reduced or eliminated.

CULTURE OF BLAME

So what is worse than knowing that mistakes are going to happen? The third barrier to decreasing errors is working in an environment in which a culture of blame is the foundation. Who has not heard someone on a nursing unit say, “If the nurse had only been more careful, this would not have happened”? Using the preceding example, when the mistake occurred, did the medical-surgical nurse have all the information to give the infusion nurse? Was the medical-surgical nurse a new graduate? And once the infusion nurse arrived, were all the needed supplies available? Were policies or protocols in place to safely practice? Many organizations have infused their facilities with the belief that if something bad happens, it must be assigned to someone and that person should be blamed, disciplined, or terminated for the mistake. How likely are nurses working in punitive environments willing to come forward and acknowledge a medication error, or a near miss of any kind? Historically, hospitals have stopped the investigation at the active error level rather than researching the latent error or root error creating an unhealthy environment. Reporting near misses is vital for improving patient safety. Not until reporting these events becomes routine will an organization be able to see trends in a certain type of occurrence. When trends are identified, change in practice can occur and a near miss will not become a direct hit. For example, several nurses report choosing a certain medication and at the time of administration it is determined by each to be incorrect. As a result of each nurse reporting a near miss, an investigation occurs that determines two look-alike medications are located side-by-side in the medication drawer. The solution could be to physically separate the two medications. Working in an environment that encourages reporting near misses will improve overall patient safety immeasurably.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ERROR

There is a “pathophysiology of error,” coined by Lucian Leape, MD, faculty member at the Harvard School of Public Health and renowned expert on health care safety. This phrase applies to all work environments including health care. In the next section, several examples of why and how mistakes are made will be covered.

RELIANCE ON WEAK ASPECTS OF COGNITION

Humans often desire to rely on their memory in order to complete tasks. This is the way many people were taught from primary school through nursing or medical school. Memorization often starts with the ABCs, and then the multiplication tables. From there, the expectation may lead to using memory as a tool to learn much more complicated facets of training such as scientific formulas, calculations, and equations. What nursing students and medical students may not be taught is that memory is faulty and not to be fully trusted. The social science term for this is “reliance on weak aspects of cognition,” and this is the first cause of error. Because something is very clear at the moment it is presented, people tend to think that it will stay that clear throughout that day and tomorrow. On a busy nursing unit, however, a nurse may be interrupted five times while walking down the hall to restart an IV. What are the chances that the nurse will remember all five of those messages accurately when charting hours later?

INTERRUPTIONS

Interruptions are the second type of cause of error. When a person stops the nurse in the hallway to deliver a message, the message deliverer does not intend to assist in causing an error but the potential is there. Some health care organizations are so aware of the danger of interruption that when a nurse is preparing medications to be administered, a vest is worn with the following inscription: “Thank you for helping me provide safe care to my patients by not disturbing me while I prepare and administer these medications.”

FATIGUE

Another cause of error is simple fatigue. While historically a badge of honor in health care, fatigue is being acknowledged as a major factor in many types of errors. Lucian Leape, MD, has said many times, “Healthcare is the only profession where fatigue is not considered a factor in errors.” Known as a sleep-deprived nation, American health care providers take that one step further by having nurses work double shifts or historically by the number of hours physicians in training spend on duty at one time. It has been estimated that being awake for 24 hours is the equivalent to having a blood alcohol level of 0.1% (Dawson and Reid, 1997). If it is illegal to drive a motor vehicle because of the impact on the body when exceeding the blood alcohol level, should it be permissible to care for patients? Health care is slowly realizing the concerns and implications. In 1984 an 18-year-old girl was admitted to a New York hospital complaining of flulike symptoms. Seven hours later she was dead. Out of this tragedy came the review of medical residents’ level of fatigue and the role it had in her death. State legislation in New York mandated limiting the hours that medical residents may work in any given week. Known as the Bell Commission, Dr. Bertrand Bell, the chairman of the committee that investigated this case, remarked, “How is it possible for anyone to be functional working an 85 hour work week? A bus driver can not do it, a pilot can not do it, so why should a neophyte doctor do it?” (Josefson, 1998). In 2001 the Accreditation Council for American Medical Education (ACAME), the agency that oversees the accreditation of medical education (similar to the oversight of hospital accreditation by The Joint Commission), now requires a limitation on the number of work hours for physicians in training. Many hospitals have taken this lesson and expanded it to nursing by instituting a policy that does not allow nurses to work more than 12 hours at a time. However, in this time of nursing shortages, many organizations do allow nurses to work extra hours in order to meet the staffing demands. Patients come first, and when there are vacancies or illnesses in the health care organization, nurses will step up and do what it takes to provide patient care.

TIME PRESSURE

Time pressure in health care also adds to the problem of inducing errors in the workplace. In the American environment, where federal reimbursement is decreasing, health care resources are stretched thin, and shortages of nurses abound, time pressures add to the pathophysiology of error. Fewer nurses are caring for more and sicker patients, leaving greater room for error. Because patients are having more diagnostic tests and surgeries, patients are more mobile across the health care settings than ever. Also known as “performance pressure,” the stress to move patients through the health care system has a domino effect on the entire health care system, leaving everyone fatigued, stressed, and accident-prone.

HAND-OFFS

Communication “hand-offs” are another very common way that patient safety is compromised. Most clinicians do not realize how many times information is passed from one person to another in the course of one patient transaction. Hand-offs are like the children’s game of “rumor,” where a sentence is whispered in the ear of one child and the message is whispered to another and another until the last child verbalizes the sentence. As would be expected, the final version of the sentence bears no resemblance to the original statement; so it is with passing information from one clinician to another. Infusion nurses often receive orders that are hand-written and nonstructured, where deciphering the exact order is sometimes difficult. Equally unsafe, the infusion nurse may receive instructions from a nurse who is verbally passing the instructions to another caregiver in a nonstructured format from yet another nurse.

Errors can occur anywhere along the chain of information hand-offs in a multifaceted, complex health care system. Some of these providers will have multiple patients who could be traveling anywhere along this continuum of care, with the likelihood for error increasing exponentially.

MEDICATION TERMINOLOGY

Adding to the contributing factors for error already discussed is a world of medications that have hundreds of look-alike/sound-alike names. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is, among other things, to advance public health by promoting safe and proper use of medications. MEDMARX® is an anonymous Internet-based program that is used by health care organizations to report, track, and analyze medication errors. Since it was created in 1998, hospitals across the nation have voluntarily provided 1.2 million reports of medication errors. The eighth annual USP MEDMARX® report, published in 2008, indicated that more than 1400 commonly used drugs are involved in look-alike/sound-alike drug errors. The MEDMARX® report found that 1.4% of these errors resulted in patient harm. It was also estimated that seven of these errors either caused patient death or significantly contributed to death. From these 1400 drugs, the USP determined that there were 3170 pairs of drugs that are often mistaken for the other (Thompson, 2008 and U.S. Pharmacopeia 8th annual MEDMARX, 2008).

STANDARDIZATION

Nonstandard procedures and nonstandard environments are also a cause for clinicians to inadvertently compromise patient safety. The way to perform any procedure may differ when practices are determined by individual practitioners. Until the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) began its drive to standardize the process for the placement of central lines, each caregiver tended to perform the insertion as trained by the individual’s instructor or mentor. Not until clearly defined steps were outlined and the concept of “bundling” taught, did the infection rate for bloodstream infections start to significantly decrease in health care organizations. Bundling is the concept that multiple steps in a process must be followed 100% of the time in order to decrease the likelihood of error. Environments that are standardized improve efficiency and decrease error for infusion nurses. Safety is improved for infusion nurses when the following occur:

• Carts are fully stocked with items clustered related to use.

• Shelves are labeled.

• Carts and equipment are consistently found in the same place.

Although individuality is to be commended, standardized procedures, treatments, and environments increase safety and decrease error in health care.

KNOWLEDGE BASE

An expanding knowledge base is another cause of error in health care. Information that was learned while in nursing school becomes outdated and sometimes obsolete within a couple of years of postgraduate practice. Within the field of medicine, one study indicated that an internist would need to read 20 newly published articles a day, 365 days a year (and remember all that new information) to keep abreast of the latest scientific information in that chosen specialty (Shaneyfelt, 2001). Nursing would be no different. Obviously this is an impossibility; errors will be made because of the expanding knowledge base within one’s field.

PARADIGM SHIFTS

Although the term “paradigm shift” has become clichéd in many ways, the concept is quite relevant in health care. A paradigm is the way one thinks based on his/her beliefs and environment. Thomas Kuhn (1970), a professor and writer on the history of science, coined the phrase “paradigm shift” in 1960 to indicate the ways humans shift or transition one way of thinking to another. Clinicians in health care often feel comfortable practicing the way they were trained during school, even though science may indicate that new ways of practice are better. This line of thought reflects back to the expanded knowledge base where a nurse cannot practice according to the idea that information learned 5 or 10 years ago is the current method of practice.

Lacking the ability to address a paradigm shift is another way patient safety can suffer. The key components of the central line bundle are hand hygiene, maximal barrier precautions upon insertion, chlorhexidine skin antisepsis, optimal catheter site selection (with the subclavian vein as the preferred site for nontunneled catheters), and daily review of line necessity with prompt removal when unnecessary. One of the biggest drawbacks by many clinicians who have been inserting PICCs for years was the need to wear maximal barrier precautions. It was considered highly unnecessary and would slow down patient care (remember the “time pressure” contribution to error). Infusion nurses had not been trained to wear maximal barrier precautions; so why would one start now (expanding knowledge base)? Only when clinicians could see that changing a traditional process could actually decrease infection did the thought of changing one’s practice—shifting one’s paradigm—demonstrate reductions in infection rates.

PATIENT SAFETY

Most nurses were trained that education was all that was needed to make improvements and then, if needed, to re-educate. While no one would disagree that education is crucial in the delivery of safe health care, the idea that education alone will improve safety is faulty. The role of human factors’ research is a concept that nurses most likely were not taught in school. However, the impact it makes on safety in the workplace is enormous. The science of studying humans and the environments in which they work is termed human factors. For example, under what conditions is the work completed? What kinds of tools are used in order to complete the work? What constraints occur in the workplace? By taking these variables into account, work environments can be made safer and more efficient. In infusion nursing, one of the best examples is how human factors influenced the design of the “smart pump.” Before the new design, a nurse would stand at an IV container/administration set and count drops to calculate flow rates. Medications would be added and tape would be placed on the container indicating such factors as dosing and flow rate. This was dangerous in many ways, but at the time there was no safe alternative. Historically, one of the most common causes of medication errors is that resulting from reliance on these weak aspects of cognition. Often, medications being infused are “high-hazard” medications and, as discussed previously, once an error reaches a patient, the chain of events is so tightly coupled that it is difficult to mitigate its effects. The smart pump has made a positive impact in this area. A smart pump utilizes special software targeted at eliminating the reliance on weak aspects of cognition. This design has incorporated the human factors associated with the infusion and the staff nurses performing this task but has eliminated much of the human variability of administering fluid and medication. Infusion pumps are now fitted with safeguards that have the ability to identify and correct many nurse programming errors before the error reaches the patient. The infusion pump can trigger an alarm that notifies a nurse when drug parameters are either too high or too low. Infusion pumps also have the ability to stop the administration of medication doses identified to be extremely unsafe. Calculating the rate into the pump allows for more consistent administration of the prescribed amount of the solution or medication. However, errors are still possible when an infusion pump allows clinicians to override limits or warnings.

WAYS TO IMPROVE SAFETY AND EFFICIENCY

This section will address several ways that using human factors’ research improves the safety and efficiency of the nurse. In 2006 The Joint Commission (TJC) identified communication breakdowns, estimated at roughly 65%, as the number one root cause of sentinel events in hospitals. A sentinel event is an unexpected occurrence that involves serious physical or psychological injury to a patient or one that causes death (TJC, 2008a). By root cause, The Joint Commission means that while the actual sentinel event may have been “wrong site surgery,” the real root cause of that sentinel event was the result of a communication breakdown between the surgeon and the nurse, which led to the sentinel event.

Reduce and improve hand-offs

Improving communication hand-offs is the first example of how human factors’ research will improve patient safety. Historically, the way in which patient information is communicated, whether it is transferred from one unit to another or at change of shifts, has been determined by the nurse. The report might be communicated by phone, in person, or on a tape recorder. Also, in the past the order in which the information was given and the comprehensiveness of the content were often determined by the individual. Recalling the concept of weak aspects of cognition (where the nurse relied on memory to convey a comprehensive report), there was no assurance that the correct information was reported every time. There was often the illusion that communication had occurred on the part of the nurse giving a report. Communication hand-off tools have become widely used to ensure that vital information is passed on to the next caregiver. A communication form template encourages the nurse giving report to systematically proceed through vital information by having a tool on hand. The nurse is no longer relying on memory to communicate everything that needs to be conveyed.

Hand-off tools

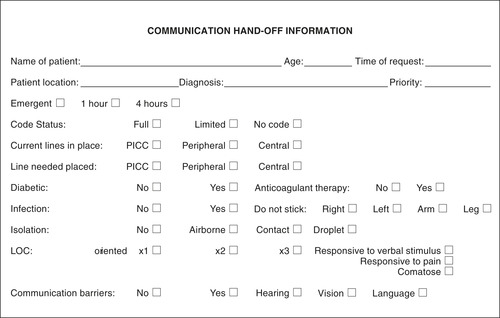

Hand-off tools can be used in a variety of settings whether it is a change of shift report or whether a patient is being temporarily transferred into another department’s care for a specific procedure. For infusion nurses, a hand-off tool can be used when a call is made requesting infusion nursing services. One of the most common error types in infusion nursing is the lack of consistent information obtained from the requesting unit before arrival. The tool will assist in the prioritization of care and arriving at the new site better prepared to immediately begin providing care. There is no one standard hand-off tool and organizations can modify current tools to fit their individual needs (Figure 7-1).The bottom line is to improve patient safety in any way that can be accomplished.

|

| FIGURE 7-1 Communication hand-off information. |

SBAR

It comes as no surprise to say that nurses and physicians are educated differently, not only in content but also in style. Nurses are encouraged to be collaborators and to seek consensus, and they are taught that although they can describe patient conditions, they cannot diagnose them. So in discussing patient care with colleagues, narrative, descriptive explanations are used. Physicians, on the other hand, are taught to be decision-makers, to problem-solve, and then to diagnose. So in crucial situations when vital information needs to be conveyed between these two clinicians, many times each is left frustrated with the other. Communication styles just do not necessarily mesh. A bridge to that communication conflict is a communication tool that actually had its origins in the nuclear submarine field. After the IOM study was published in 2000 and the gravity of up to 98,000 lost lives annually was realized in the health care community, a group of health care providers at Kaiser Permanente met to discuss how medical errors could be decreased. Out of one of these discussions came the communication tool SBAR (pronounced S-BAR). A team member, a former safety officer on a nuclear submarine, explained how vital information was communicated quickly, succinctly, and in the same manner each time. During this strategy session, the concept of SBAR was born (Monroe, 2006), which indicates the following:

• Situation—State the problem (the reason for the call) in 5 to 10 seconds.

• Background—Put the situation in context. Provide objective information.

• Assessment—State the problem.

• Recommendation—Recommend what needs to be done. What does the physician need to do?

By standardizing communication through developing a template, efficiency is increased and patient safety improved (Figure 7-2). Health care organizations across the nation have adopted this communication strategy for use in a variety of situations. Although SBAR is most commonly used when nurses and physicians communicate with each other about a patient issue, it is being used successfully with pharmacists and others. The most important point is this communication strategy works both ways. In health care organizations that have fully integrated this method, physicians call and convey information using SBAR and nurses call and communicate patient information via SBAR to the physicians as well. The following is an example of how this communication technique is used:

|

| FIGURE 7-2 SBAR communication tool. (Adapted from Dingley C, Daugherty K, Derieg MK, and persing R: Improving patient safety through provider communication strategy enhancements, Accessed 1/5/09 from www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/advances2/vol3/advances-dingley_14.pdf). |

• S (Situation)—Dr. Smith, this is Susan Carter. I am the nurse taking care of Daniel Mason in room 1069. He has developed pain and burning at his left forearm IV site.

• B (Background)—Mr. Mason is a 63-year-old male with a history of hypertension, renal insufficiency, and congestive heart failure (CHF), admitted with exacerbation of his CHF. He was started yesterday on intravenous dopamine in an attempt to enhance his urine output. The dopamine is infusing into the site where he has developed symptoms.

• A (Assessment)—His venipuncture site is reddened and edematous. It appears that he has a dopamine extravasation.

• R (Recommendation)—I have discontinued the IV catheter and elevated the arm. I feel he may benefit from phentolamine and would like you to evaluate the patient.

This method of communication will only occur with acceptance from all disciplines. Training on how to use the tool is vital. After training, many hospitals place a laminated SBAR form near telephones and in dictation areas to use as a visual trigger in utilizing this strategy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access