Nursing Care of Mother and Infant During Labor and Birth

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Discuss specific cultural beliefs the nurse may encounter when providing care to a woman in labor.

5. Describe how the four Ps of labor interrelate to result in the birth of an infant.

7. Explain common nursing responsibilities during the labor and birth.

8. Explain how false labor differs from true labor.

10. Describe the care of the newborn immediately after birth.

Key Terms

accelerations (p. 134)

absent variability (p. 134)

acrocyanosis (ăk-rō-sī-ă-NŌ-sĭs, p. 151)

adjustment (p. 140)

amnioinfusion (ăm-nē-ō-ĭn-FYŪ-zhŭn, p. 137)

amniotomy (ăm-nēŎT-ŏ-mē, p. 137)

baseline fetal heart rate (p. 132)

baseline variability (p. 134)

bloody show (p. 126)

cold stress (p. 150)

coping (p. 140)

crowning (p. 144)

decelerations (p. 134)

dilate (p. 120)

doula (DŪ-lă, p. 143)

efface (ĕ-FĀS, p. 120)

episodic changes (p. 134)

fetal bradycardia (p. 133)

fetal tachycardia (p. 134)

fontanelle (FŎN-tă-nĕl, p. 123)

late decelerations (p. 136)

Leopold’s maneuver (p. 131)

lie (p. 123)

marked variability (p. 134)

moderate variability (p. 134)

molding (p. 123)

neutral thermal environment (p. 150)

nitrazine test (p. 138)

nuchal cord (NŪ-kăl kŏrd, p. 135)

ophthalmia neonatorum (ŏf-THĂL-mē-ă nē-ō-nă-TŎR-ăm, p. 152)

periodic changes (p. 134)

prolonged decelerations (p. 136)

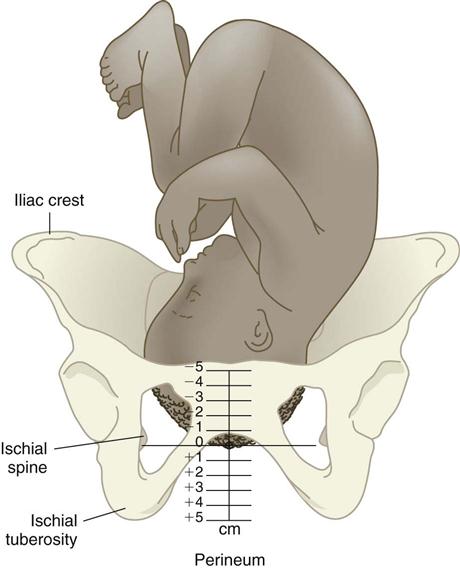

station (p. 127)

sutures (p. 123)

uteroplacental insufficiency (yū-tăr-ō-plă-SĔN-tăl ĭn-sŭ-FĬSH-ăn-sē, p. 136)

vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) (p. 144)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

Childbirth is a normal physiological process that involves the health of the mother and a fetus who will become part of our next generation. The nursing care is unique because every nursing intervention involves the welfare of two patients and the use of skills from medical-surgical and pediatric nursing, psychosocial and communication skills, and specific skills involved in obstetric care. In addition, labor and delivery are often a family affair, with fathers, grandparents, and others closely involved. The details of this experience are often remembered for a long time by each family participant.

The privacy and rights of the mother must be protected, the policies and procedures of the institution must be considered, and the nurse must be familiar with the scope of practice set out by the state board of nursing. Recent changes in the management of labor and delivery include practices related to induction and augmentation of labor, fetal monitoring techniques, maternal positions, types of analgesia offered, and assistive devices such as vacuum extraction.

This chapter provides information concerning the birth process and the nursing responsibilities during labor and delivery.

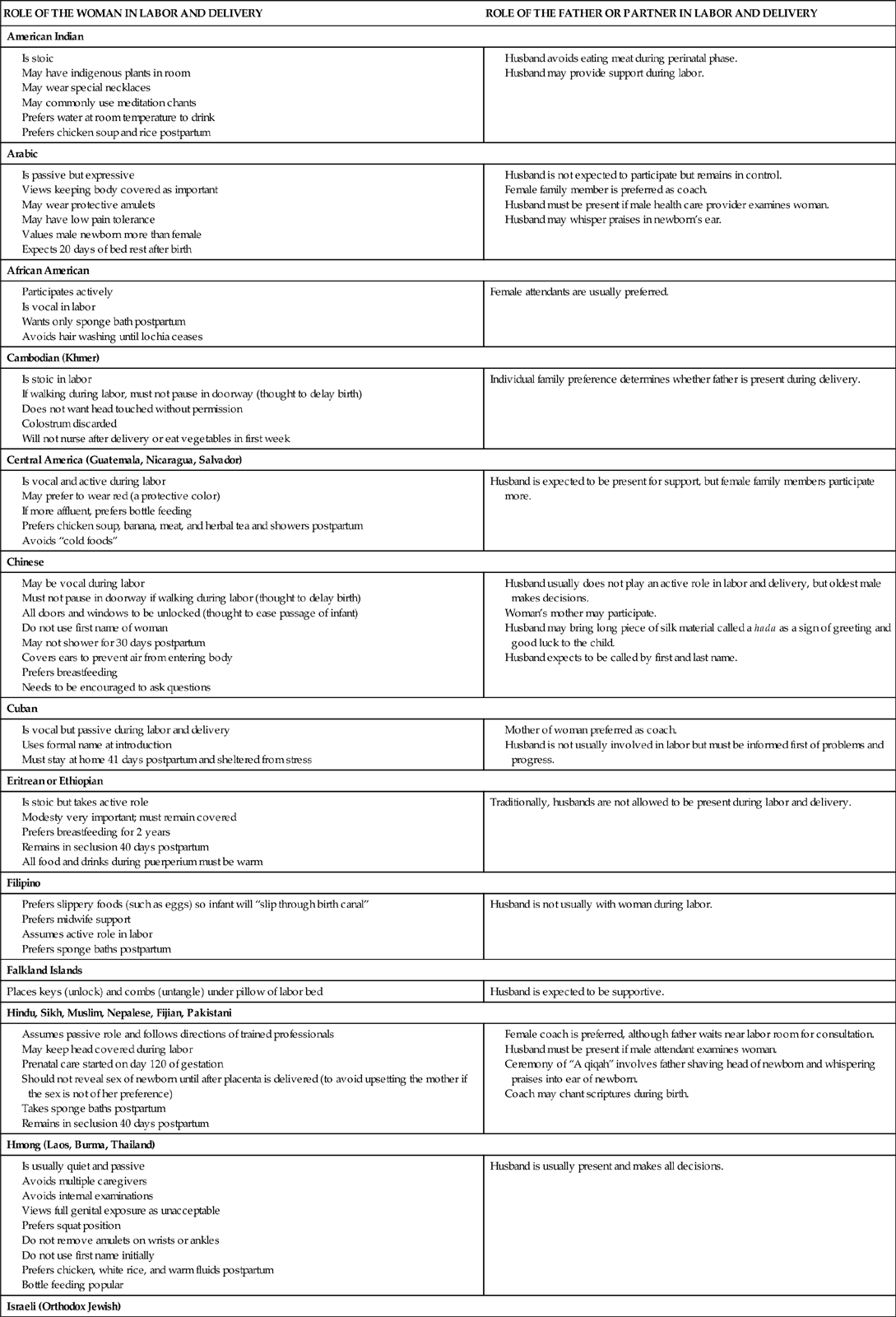

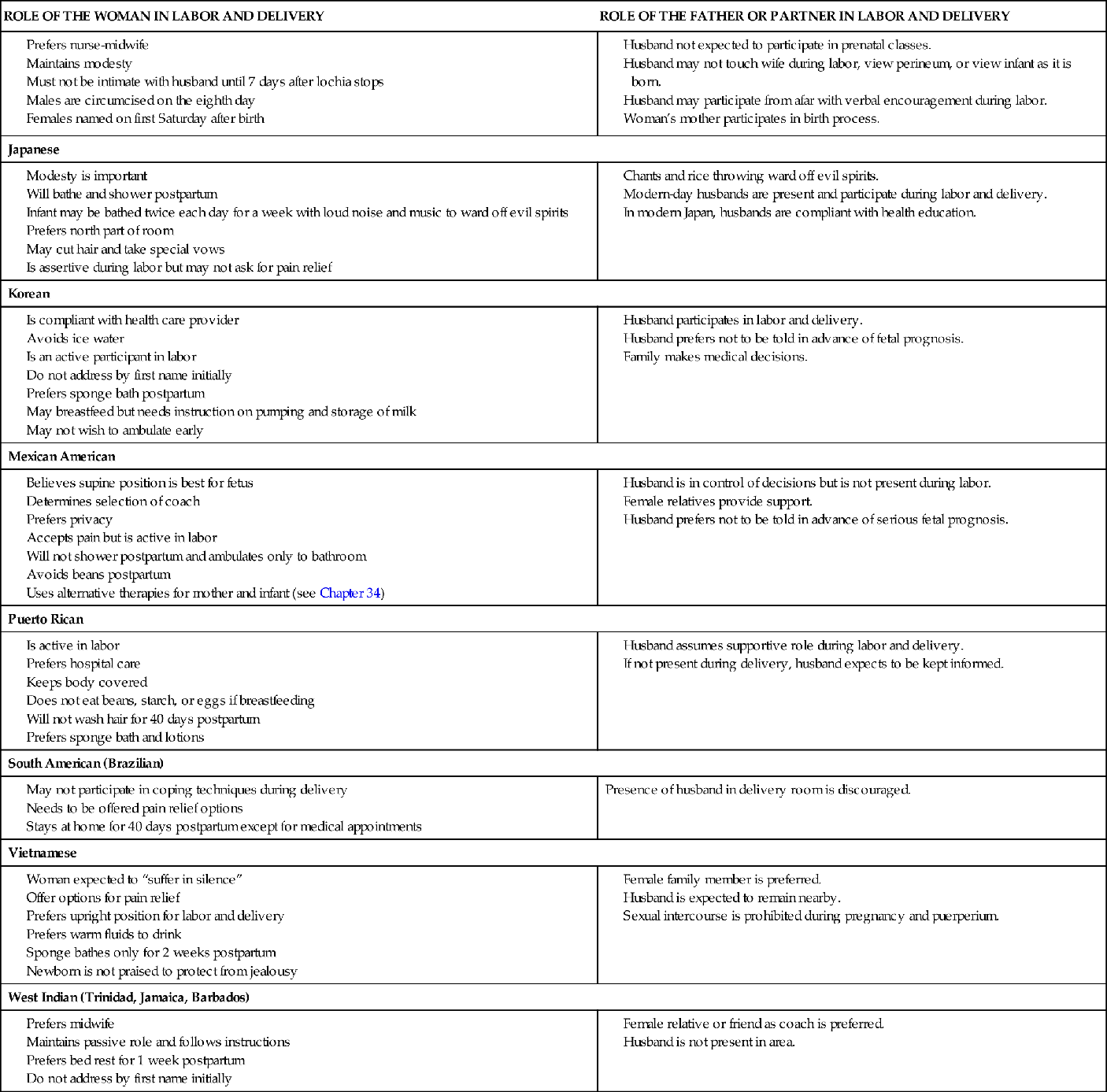

Cultural Influence on Birth Practices

The needs of the woman giving birth may be influenced by her cultural background, which may be very different from that of the nurse but must be understood and respected. In a multicultural environment, nothing is routine. Patient and cultural preferences require flexibility on the part of the nurse. Women of most cultures prefer the presence of a support person at all times during labor and delivery, and that can include the father or family as well as professional staff. The United States is a multicultural society. Table 6-1 lists common traditional birth practices of selected cultures. The practices of these cultural groups may vary depending on the amount of time they have been in the United States and the degree to which they have assimilated into the culture.

Table 6-1

Birth Practices of Selected Cultural Groups

Data from Lipson, J.G., & Dibble, S.L. (2005). Culture and nursing care (2nd ed.). San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing; Lowdermilk, D.L., & Perry, S.E., (2007). Maternity and women’s health care (9th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby; Perry, S.E., Hockenberry, M.J., Lowdermilk, D.L., & Wilson, D. (2010). Maternal and child nursing care (4th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby; Murasaki, S. (1996). Diary of Lady Murasaki. New York: Penguin Books.

Settings for Childbirth

Depending on facilities available in the area and the risks for complications, a woman can choose among three settings in which to deliver her child. Most women give birth in the hospital, whereas others choose freestanding birth facilities or their own home with a nurse-midwife or lay midwife in attendance.

Hospitals

The woman who chooses a hospital birth may have a “traditional” setting, in which she labors, delivers, and recovers in separate rooms. After the recovery period, she is transferred to the postpartum unit. A more common setting for hospital maternity care is the birthing room, often called a labor-delivery-recovery (LDR) room. The woman labors, delivers, and recovers all in the same room. She is then transferred to the postpartum unit for continuing care. The appearance of the birthing room is more homelike than institutional. The fully functional birthing bed has wood trim that hides its utilitarian purpose (Figure 6-1). The beds have receptacles for various fittings, such as a “squat bar,” which facilitates squatting during second-stage labor. The foot of the bed can be detached or rolled away to reveal foot supports or stirrups.

Another hospital birth setting is a single-room maternity care arrangement, often called a labor-delivery-recovery-postpartum (LDRP) room. It is similar to the LDR room, but the mother and infant remain in the same room until discharge.

Advantages of hospital-based birth settings include the following:

Freestanding Birth Centers

Some communities have birth centers that are separate from, although usually near, hospitals and are similar to outpatient surgical centers. Many birth centers are operated by full-service hospitals and are close enough for easy transfer if the mother, fetus, or newborn develops complications. Certified nurse-midwives often attend the births. Advantages of freestanding birth centers include the following:

Disadvantages include the following:

Home

Some women give birth at home. Many factors enter into their decision, and most families have carefully weighed the pros and cons of their choice. Advantages of a home birth include the following:

• Control over persons who will or will not be present for the labor and birth, including children

• No risk of acquiring pathogens from other patients

• A low-technology birth, which is important to some families

Disadvantages vary with the location and may include the following:

Components of the Birth Process

Four interrelated components, often called the “four Ps,” make up the process of labor and birth: the powers, the passage, the passenger, and the psyche. These factors are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Other factors that influence the progress of labor include preparation, such as attendance at prenatal classes; position, horizontal or vertical; professional help, such as knowledgeable nurses in attendance who explain and coach; the place or setting, because a lack of privacy and changes in shift personnel can interrupt rapport; procedures, such as internal examinations; and people, such as the presence of supportive family members (VandeVusse, 1999).

The Powers

The powers of labor are forces that cause the cervix to open and that propel the fetus downward through the birth canal. The two powers are the uterine contractions and the mother’s pushing efforts.

Uterine Contractions

Uterine contractions are the primary powers of labor during the first of the four stages of labor (from onset until full dilation of the cervix). Uterine contractions are involuntary smooth muscle contractions; the woman cannot consciously cause them to stop or start. However, their intensity and effectiveness are influenced by a number of factors, such as walking, drugs, maternal anxiety, and vaginal examinations.

Effect of Contractions on the Cervix.

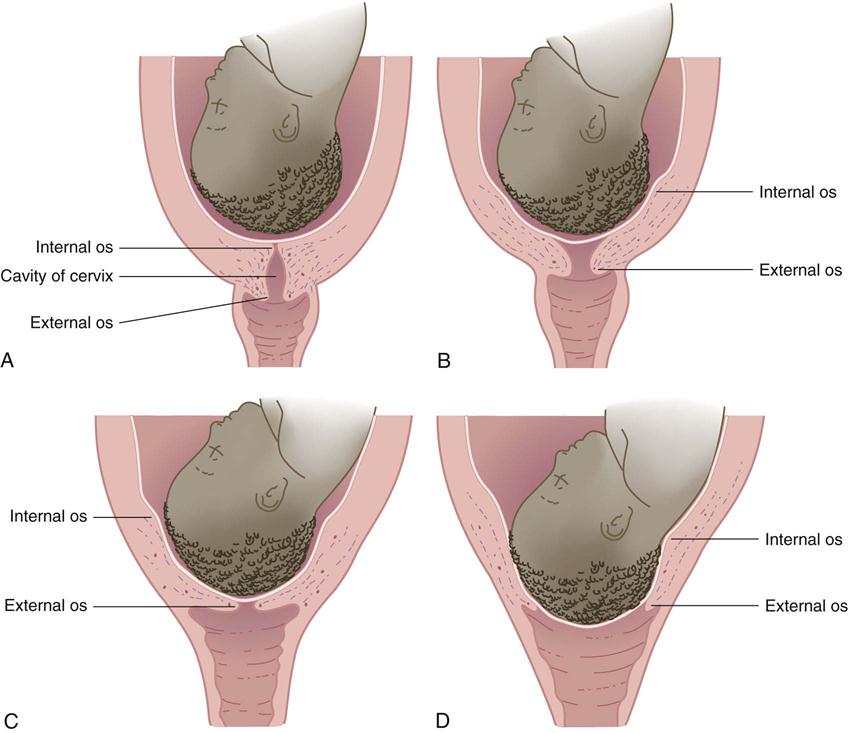

Contractions cause the cervix to efface (thin) and dilate (open) to allow the fetus to descend in the birth canal (Figure 6-2). Before labor begins, the cervix is a tubular structure about 2 to 3.8 cm long. Contractions simultaneously push the fetus downward as they pull the cervix upward (an action similar to pushing a ball out the cuff of a sock). This causes the cervix to become thinner and shorter. Effacement is determined by a vaginal examination and is described as a percentage of the original cervical length. When the cervix is 100% effaced, it feels like a thin, slick membrane over the fetus.

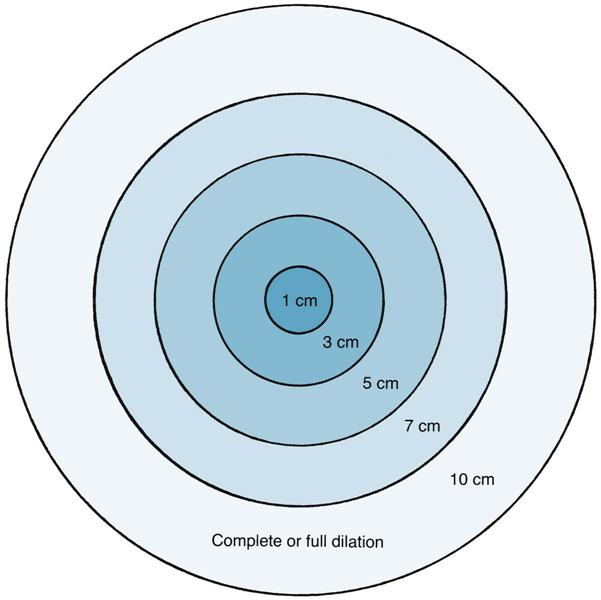

Dilation of the cervix is determined during a vaginal examination. Dilation is described in centimeters, with full dilation being 10 cm (Figure 6-3). Both dilation and effacement are estimated by touch rather than being precisely measured.

Phases of Contractions.

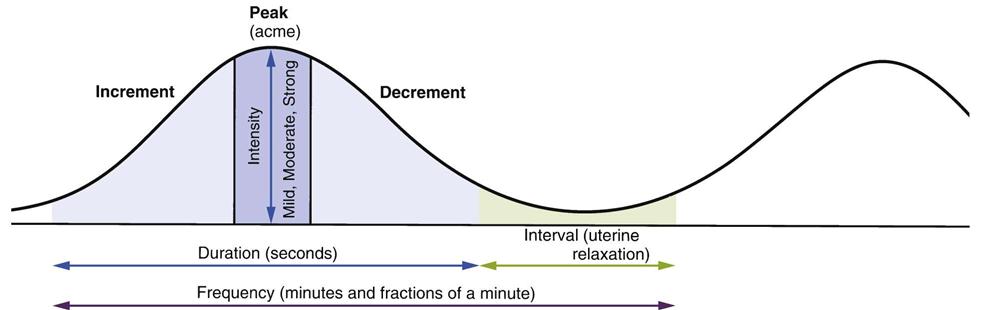

Each contraction has the following three phases (Figure 6-4):

Contractions are also described by their average frequency, duration, intensity, and interval.

Frequency.

Frequency is the elapsed time from the beginning of one contraction until the beginning of the next contraction. Frequency is described in minutes and fractions of minutes, such as “contractions every  minutes.” Contractions occurring more often than every 2 minutes may reduce fetal oxygen supply and should be reported.

minutes.” Contractions occurring more often than every 2 minutes may reduce fetal oxygen supply and should be reported.

Duration.

Duration is the elapsed time from the beginning of a contraction until the end of the same contraction. Duration is described as the average number of seconds for which contractions last, such as “duration of 45 to 50 seconds.” Persistent contraction durations longer than 90 seconds may reduce fetal oxygen supply and should be reported.

Intensity.

Intensity is the approximate strength of the contraction. In most cases, intensity is described in words such as “mild,” “moderate,” or “strong,” which are defined as follows:

Interval.

The interval is the amount of time the uterus relaxes between contractions. Blood flow from the mother into the placenta gradually decreases during contractions and resumes during each interval. The placenta refills with freshly oxygenated blood for the fetus and removes fetal waste products. Persistent contraction intervals shorter than 60 seconds may reduce fetal oxygen supply.

Maternal Pushing

When the woman’s cervix is fully dilated, she adds voluntary pushing to involuntary uterine contractions. The combined powers of uterine contractions and voluntary maternal pushing in stage 2 of labor propel the fetus downward through the pelvis. Most women feel a strong urge to push or bear down when the cervix is fully dilated and the fetus begins to descend. However, factors such as maternal exhaustion or sometimes epidural analgesia (see Chapter 7) may reduce or eliminate the natural urge to push. Some women feel a premature urge to push before the cervix is fully dilated because the fetus pushes against the rectum. This should be discouraged because it may contribute to maternal exhaustion and fetal hypoxia.

The Passage

The passage consists of the mother’s bony pelvis and the soft tissues (cervix, muscles, ligaments, and fascia) of her pelvis and perineum (see Chapter 2 for a review of the structure of the bony pelvis).

Bony Pelvis

The pelvis is divided into the following two major parts: (1) the false pelvis (upper, flaring part); (2) the true pelvis (lower part). The true pelvis, which is directly involved in childbirth, is further divided into the inlet at the top, the midpelvis in the middle, and the outlet near the perineum. It is shaped somewhat like a curved cylinder or a wide, curved funnel. The measurements of the maternal bony pelvis must be adequate to allow the fetal head to pass through, or cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) will occur, and a cesarean birth may be indicated.

Soft Tissues

In general, women who have had previous vaginal births deliver more quickly than women having their first births because their soft tissues yield more readily to the forces of contractions and pushing efforts. This advantage is not present if the woman’s prior births were cesarean. Soft tissue may not yield as readily in older mothers or after cervical procedures that have caused scarring.

The Passengers

The passengers are the fetus, the placenta (afterbirth), amniotic membranes, and amniotic fluid. Because the fetus usually enters the pelvis head first (cephalic presentation), the nurse should understand the basic structure of the fetal head.

The Fetus

Fetal Head.

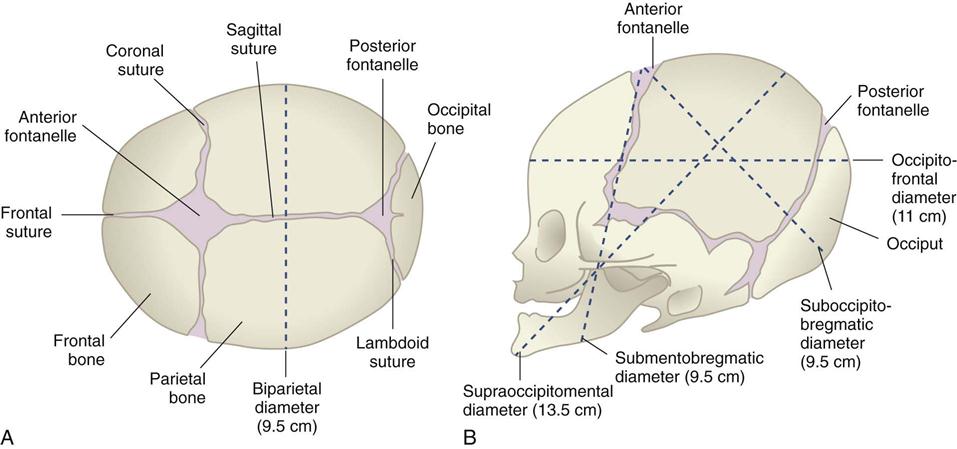

The fetal head is composed of several bones separated by strong connective tissue, called sutures (Figure 6-5). A wider area called a fontanelle is formed where the sutures meet. The following two fontanelles are important in obstetrics:

The sutures and fontanelles of the fetal head allow it to change shape as it passes through the pelvis (molding). They are important landmarks in determining how the fetus is oriented within the mother’s pelvis during birth.

The main transverse diameter of the fetal head is the biparietal diameter, which is measured between the points of the two parietal bones on each side of the head. The anteroposterior diameter of the fetal head can vary depending on how much the head is flexed or extended.

Lie.

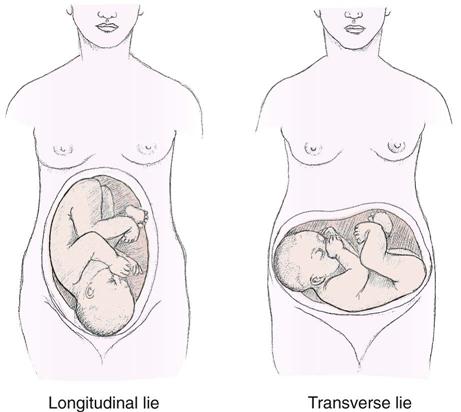

Lie describes how the fetus is oriented to the mother’s spine (Figure 6-6). The most common orientation is the longitudinal lie (greater than 99% of births), in which the fetus is parallel to the mother’s spine. The fetus in a transverse lie is at right angles to the mother’s spine. The transverse lie may also be called a shoulder presentation. In an oblique lie, the fetus is between a longitudinal lie and a transverse lie.

Attitude.

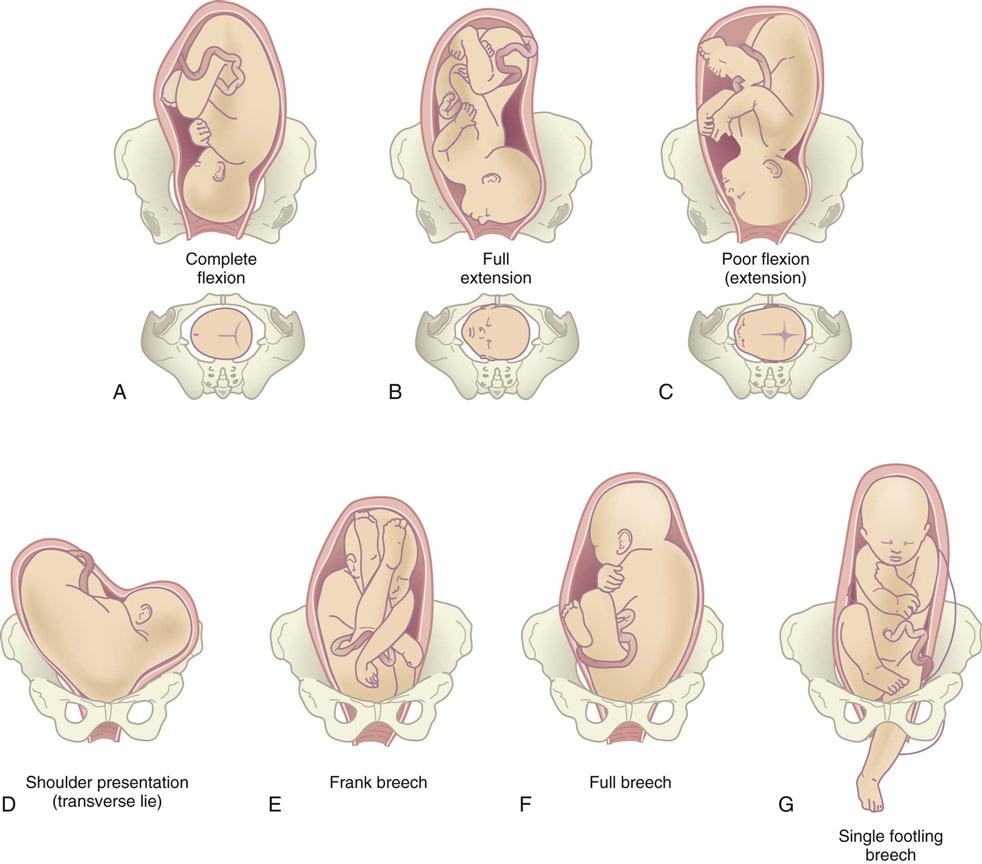

The fetal attitude is normally one of flexion, with the head flexed forward and the arms and the legs flexed. The flexed fetus is compact and ovoid and most efficiently occupies the space in the mother’s uterus and pelvis. Extension of the head, the arms, and/or the legs sometimes occurs, and labor may be prolonged.

Presentation.

Presentation refers to the fetal part that enters the pelvis first. The cephalic presentation is the most common. Any of the following four variations of cephalic presentations can occur, depending on the extent to which the fetal head is flexed (Figure 6-7):

2. Military presentation: The fetal head is neither flexed nor extended.

4. Face presentation: The head is fully extended and the face presents.

The next most common presentation is the breech, which can have the following three variations (see Figure 6-7, E to G):

Many women with a fetus in the breech presentation have cesarean births because the head, which is the largest single fetal part, is the last to be born and may not pass through the pelvis easily because flexion of the fetal head cannot occur (see Figure 8-6, p. 190). After the fetal body is born, the head must be delivered quickly so the fetus can breathe; at this point, part of the umbilical cord is outside the mother’s body and the remaining part is subject to compression by the fetal head against the bony pelvis.

When the fetus is in a transverse lie, the fetal shoulder enters the pelvis first. A fetus in this orientation must be delivered by cesarean section because it cannot safely pass through the pelvis.

Position.

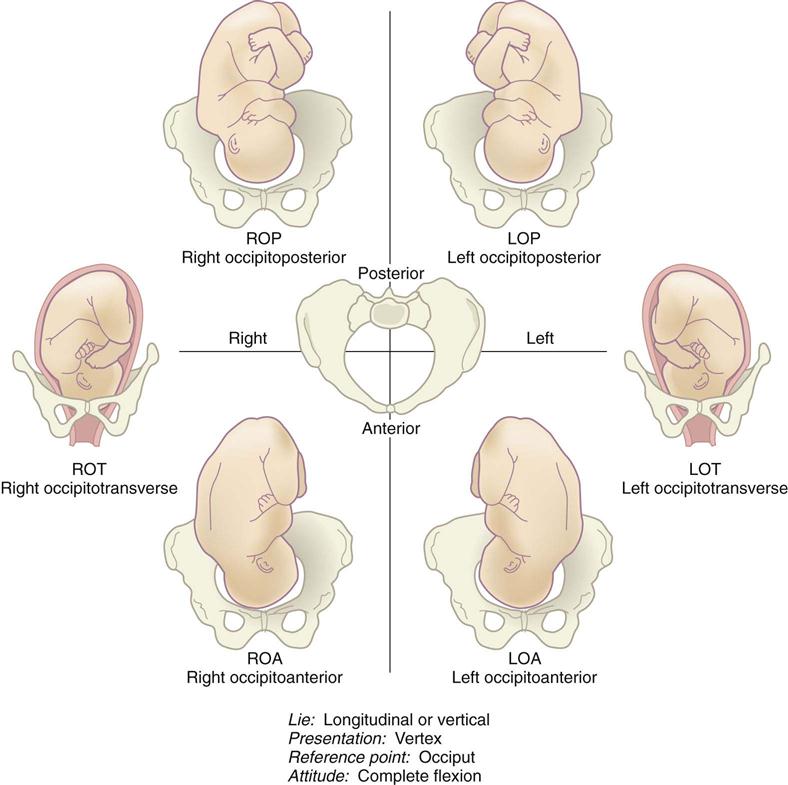

Position refers to how a reference point on the fetal presenting part is oriented within the mother’s pelvis. The term occiput is used to describe how the head is oriented if the fetus is in a cephalic vertex presentation. The term sacrum is used to describe how a fetus in a breech presentation is oriented within the pelvis. The shoulder and back are reference points if the fetus is in a shoulder presentation.

The maternal pelvis is divided into four imaginary quadrants: right and left anterior and right and left posterior. If the fetal occiput is in the left front quadrant of the mother’s pelvis, it is described as left occiput anterior. If the sacrum of a fetus in a breech presentation is in the mother’s right posterior pelvis, it is described as right sacrum posterior.

Abbreviations describe the fetal presentation and position within the pelvis (Box 6-1). Three letters are used for most abbreviations:

Figure 6-8 shows various fetal presentations and positions.

The Psyche

Childbirth is more than a physical process; it involves the woman’s entire being. Women do not recount the births of their children in the same manner that they do surgical procedures. They describe births in emotional terms, such as those they use to describe marriages, anniversaries, religious events, or even deaths. Families often have great expectations about the birth experience, and the nurse can promote a positive childbearing experience by incorporating as many of the family’s birth expectations as possible.

A woman’s mental state can influence the course of her labor. For example, the woman who is relaxed and optimistic during labor is better able to tolerate discomfort and work with the physiological processes. By contrast, marked anxiety can increase her perception of pain and reduce her tolerance of it. Anxiety and fear also cause the secretion of stress compounds from the adrenal glands. These compounds, called catecholamines, inhibit uterine contractions and divert blood flow from the placenta.

A woman’s cultural and individual values influence how she views and copes with childbirth.

Normal Childbirth

The specific event that triggers the onset of labor remains unknown. Many factors probably play a part in initiating labor, which is an interaction of the mother and fetus. These factors include stretching of the uterine muscles, hormonal changes, placental aging, and increased sensitivity to oxytocin. Labor normally begins when the fetus is mature enough to adjust easily to life outside the uterus yet still small enough to fit through the mother’s pelvis. This point is usually reached between 38 and 42 weeks after the mother’s last menstrual period.

Signs of Impending Labor

Signs and symptoms that labor is about to start may occur from a few hours to a few weeks before the actual onset of labor.

Braxton Hicks Contractions

Braxton Hicks contractions are irregular contractions that begin during early pregnancy and intensify as full term approaches. They often become regular and somewhat uncomfortable, leading many women to believe that labor has started (see the discussion of true and false labor later in this chapter). Although Braxton Hicks contractions are often called “false” labor, they play a part in preparing the cervix to dilate and in adjusting the fetal position within the uterus.

Increased Vaginal Discharge

Fetal pressure causes an increase in clear and nonirritating vaginal secretions. Irritation or itching with the increased secretions is not normal and should be reported to the physician or certified nurse-midwife (CNM) because these symptoms are characteristic of infection.

Bloody Show

As the time for birth approaches, the cervix undergoes changes in preparation for labor. It softens (“ripens”), effaces, and dilates slightly. When this occurs, the mucous plug that has sealed the uterus during pregnancy is dislodged from the cervix, tearing small capillaries in the process. Bloody show is thick mucus mixed with pink or dark brown blood. It may begin a few days before labor, or a woman may not have bloody show until labor is under way. Bloody show may also occur if the woman has had a recent vaginal examination or intercourse.

Rupture of the Membranes

The amniotic sac (bag of waters) sometimes ruptures before labor begins. Infection is more likely if many hours elapse between rupture of the membranes and birth because the amniotic sac seals the uterine cavity against organisms from the vagina. In addition, the fetal umbilical cord may slip down and become compressed between the mother’s pelvis and the fetal presenting part. For these two reasons, women should go to the birth facility when their membranes rupture, even if they have no other signs of labor.

Energy Spurt

Many women have a sudden burst of energy shortly before the onset of labor (“nesting”). The nurse should teach women to conserve their strength, even if they feel unusually energetic.

Weight Loss

Occasionally a woman may notice that she loses 1 to 3 lb shortly before labor begins because hormonal changes cause her to excrete extra body water.

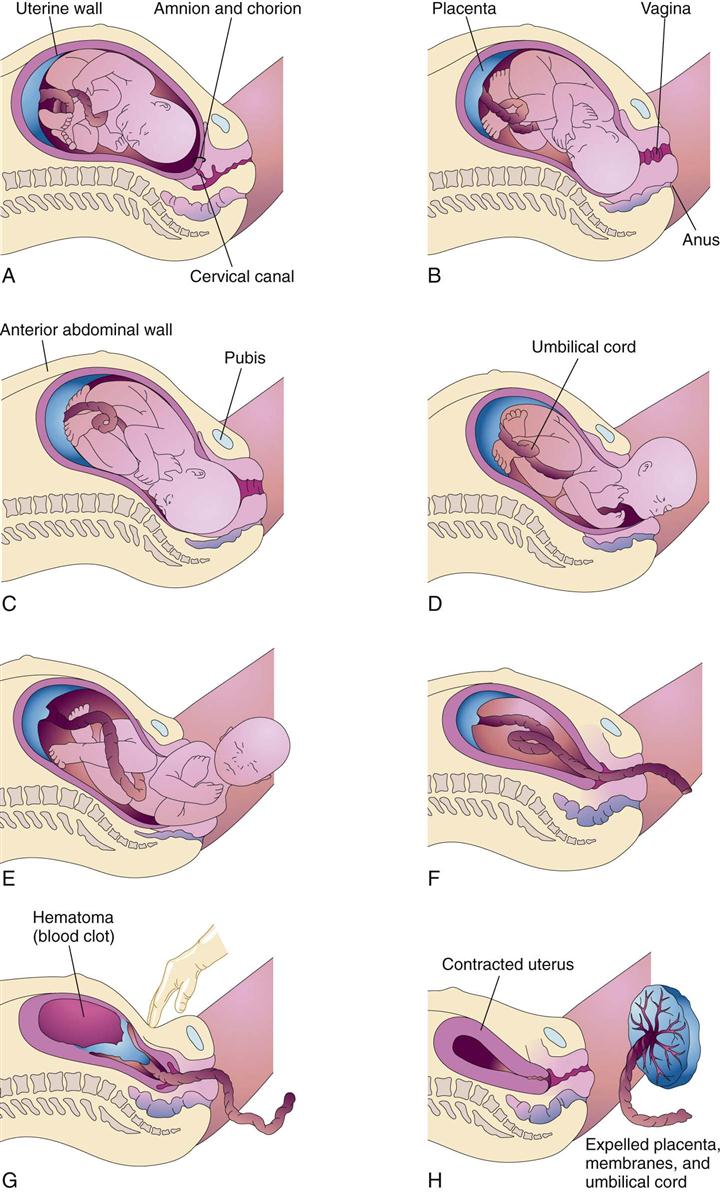

Mechanisms of Labor

As the fetus descends into the pelvis, it undergoes several positional changes so that it adapts optimally to the changing pelvic shape and size. Many of these mechanisms, also called cardinal movements, occur simultaneously (Figure 6-9).

Descent

Descent is required for all other mechanisms of labor to occur and for the infant to be born. Descent occurs as each mechanism of labor comes into play. Station describes the level of the presenting part (usually the head) in the pelvis. Station is estimated in centimeters from the level of the ischial spines in the mother’s pelvis (a 0 [zero] station). Minus stations are above the ischial spines, and plus stations are below the ischial spines (Figure 6-10). As the fetus descends, the minus numbers decrease (e.g., −2, −1) and the plus numbers increase (e.g., +1, +2).

Engagement

Engagement occurs when the presenting part (usually the biparietal diameter of the fetal head) reaches the level of the ischial spines of the mother’s pelvis (presenting part is at a 0 station or lower). Engagement often occurs before the onset of labor in a woman who has not previously given birth (a nullipara); if the woman has had prior vaginal births (a multipara), engagement may not occur until well after labor begins.

Flexion

The fetal head should be flexed to pass most easily through the pelvis. As labor progresses, uterine contractions increase the amount of fetal head flexion until the fetal chin is on the chest.

Internal Rotation

When the fetus enters the pelvis head first, the head is usually oriented so the occiput is toward the mother’s right or left side. As the fetus is pushed downward by contractions, the curved, cylindrical shape of the pelvis causes the fetal head to turn until the occiput is directly under the symphysis pubis (occiput anterior [OA]).

Extension

As the fetal head passes under the mother’s symphysis pubis, it must change from flexion to extension so it can properly negotiate the curve. To do this, the fetal neck stops under the symphysis, which acts as a pivot. The head swings anteriorly as it extends with each maternal push until it is born.

External Rotation

When the head is born in extension, the shoulders are crosswise in the pelvis and the head is somewhat twisted in relation to the shoulders. The head spontaneously turns to one side as it realigns with the shoulders (restitution). The shoulders then rotate within the pelvis until their transverse diameter is aligned with the mother’s anteroposterior pelvis. The head turns farther to the side as the shoulders rotate within the pelvis.

Expulsion

The anterior shoulder and then the posterior shoulder are born, quickly followed by the rest of the body.

Admission to the Hospital or Birth Center

Intrapartum nursing care begins before admission by educating the woman about the appropriate time to come to the facility. Nursing care includes admission assessments and the initiation of necessary procedures. Many women have false labor and are discharged after a short observation period.

When to Go to the Hospital or Birth Center

During late pregnancy the woman should be instructed about when to go to the hospital or birth center. There is no exact time, but the general guidelines are as follows:

Admission Data Collection

The nurse should observe the appropriate infection control measures when providing care in any clinical area. Water-repellent gowns, eye shields, and gloves are worn in the delivery area, and the newborn infant is handled with gloves until after the first bath. General guidelines for wearing protective clothing in the intrapartal area can be found in Appendix A.

When a woman is admitted, the nurse establishes a therapeutic relationship by welcoming her and her family members. The nurse continues developing the therapeutic relationship during labor by determining the woman’s expectations about birth and helping to achieve them. Some women have a written birth plan that they have discussed with their health care provider and the facility personnel. The woman’s partner and other family members she wants to be part of her care are included. From the first encounter, the nurse conveys confidence in the woman’s ability to cope with labor and give birth to her child.

The three major assessments performed promptly on admission are the following: (1) fetal condition, (2) maternal condition, and (3) impending (nearness to) birth.

Fetal Condition

The fetal heart rate (FHR) is assessed with a fetoscope (stethoscope for listening to fetal heart sounds), a hand-held Doppler transducer, or an external fetal monitor. When the amniotic membranes are ruptured, the color, amount, and odor of the fluid are assessed and the FHR is recorded.

Maternal Condition

The temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure are assessed for signs of infection or hypertension.

Impending Birth

The nurse continually observes the woman for behaviors that suggest she is about to give birth, including the following:

• Bearing down with contractions

• Bulging of the perineum or the fetal presenting part becoming visible at the vaginal opening

If it appears that birth is imminent, the nurse does not leave the woman but summons help or uses the call bell. Gloves should be applied in case the infant is born quickly. Emergency delivery kits (called “precip trays” for “precipitous birth”) containing essential equipment are in all delivery areas. The student should locate this tray early in the clinical experience because one cannot predict when it will be needed. The nurse’s priority is to prevent injury to the mother and infant. The nurse should don gloves and a cover gown and assist with the delivery until help arrives (Skill 6-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree