Nursing Care of Women with Complications During Pregnancy

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Explain the use of fetal diagnostic tests in women with complicated pregnancies.

3. Describe antepartum complications, their treatment, and their nursing care.

4. Identify methods to reduce a woman’s risk for antepartum complications.

5. Discuss the management of concurrent medical conditions during pregnancy.

6. Describe environmental hazards that may adversely affect the outcome of pregnancy.

7. Describe how pregnancy affects care of the trauma victim.

Key Terms

abortion (p. 82)

cerclage (sĕr-KLĂHZH, p. 82)

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (p. 90)

eclampsia (ĕ-KLĂMP-sē-ă, p. 91)

erythroblastosis fetalis (ĕ-rĭth-rō-blăs-Ō-sĭs fĕ-TĂ-lĭs, p. 96)

gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) (p. 97)

hydramnios (hī-DRĂM-nē-ŏs, p. 97)

incompetent cervix (ĭn-KŎM-pă-tănt SŬR-vĭkz, p. 82)

isoimmunization (ī-sō-ĭm-myū-nĭ-ZĀ-shŭn, p. 96)

macrosomia (măk-rō-SŌ-mē-ă, p. 98)

preeclampsia (prē-ĕ-KLĂMP-sē-ă, p. 91)

products of conception (POC) (p. 86)

teratogen (TĔR-ă-tō-jĕn, p. 107)

tonic-clonic seizures (p. 92)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

Most women have uneventful pregnancies that are free of complications. Some, however, have complications that threaten their well-being and that of their babies. Many problems can be anticipated in the course of prenatal care and thus prevented or made less severe. Others occur without warning.

Women who have no prenatal care or begin care late in pregnancy may have complications that are severe because they were not identified early. Danger signs that should be taught to every pregnant woman and reinforced at each prenatal visit are listed in the Patient Teaching box. The woman should be taught to notify her health care provider if any of these danger signs occur. A high-risk pregnancy is defined as one in which the health of the mother or fetus is in jeopardy.

The causes of high-risk pregnancies usually have the following characteristics:

• Relate to the pregnancy itself

• Occur because the woman has a medical condition or injury that complicates the pregnancy

• Result from environmental hazards that affect the mother or her fetus

• Arise from maternal behaviors or lifestyles that have a negative effect on the mother or fetus

Early and consistent assessment for risk factors during prenatal visits is essential for a positive outcome for the mother and the fetus.

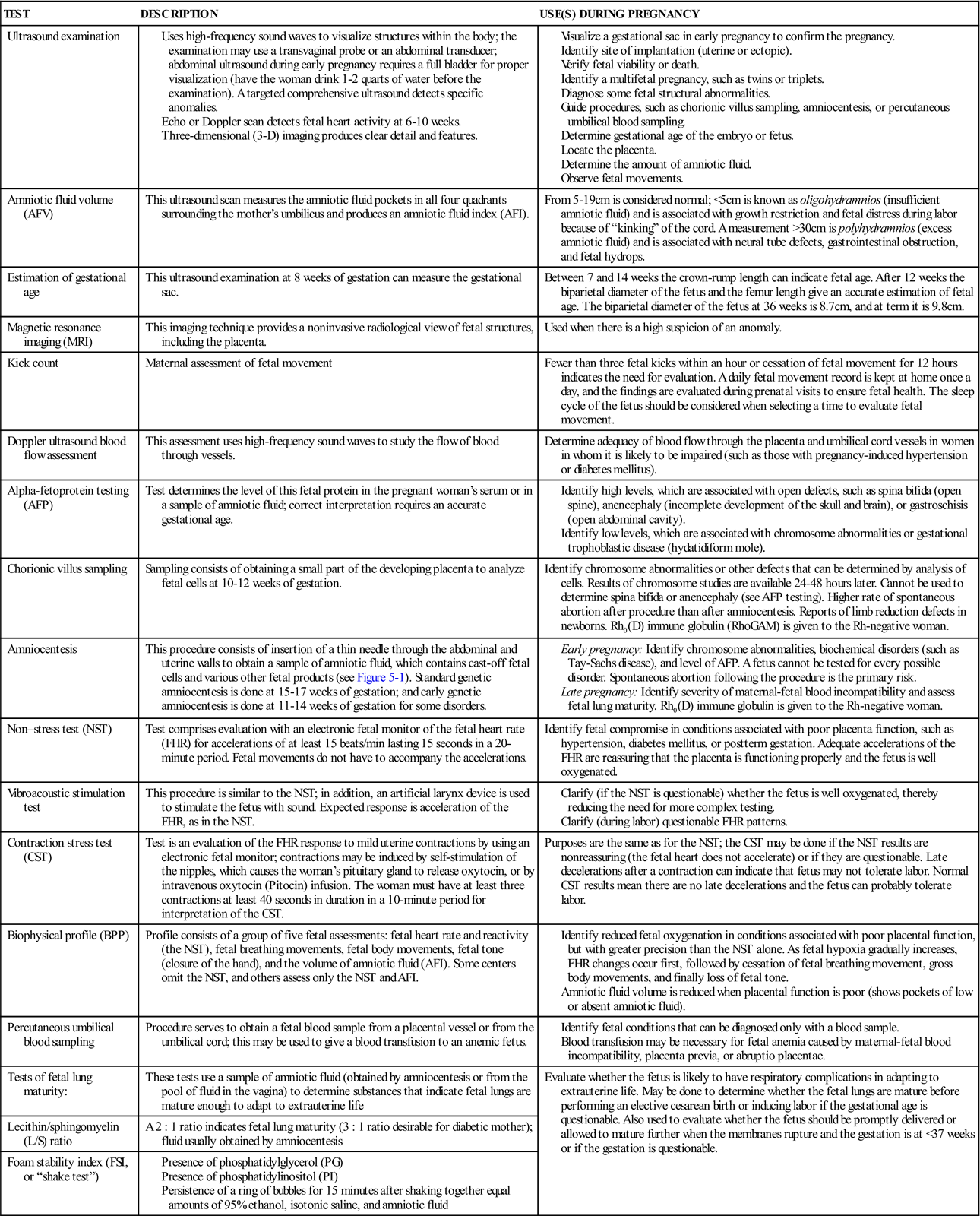

Assessment of Fetal Health

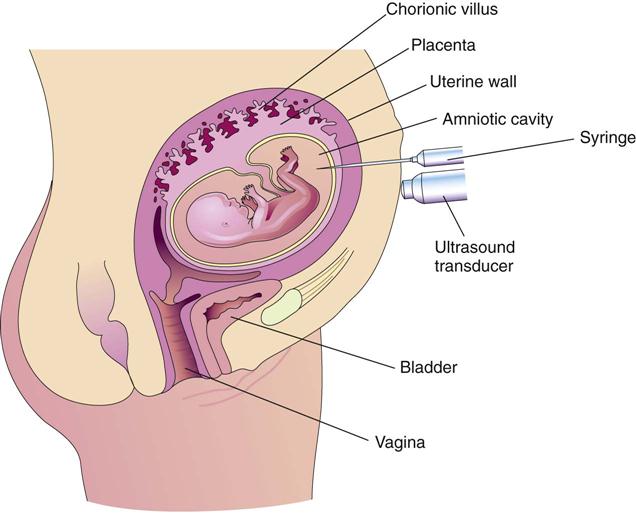

Extraordinary technical advances have enabled the management of high-risk pregnancies so that both the mother and the fetus have positive outcomes. Various tests can be used prenatally to assess the well-being of the fetus. Nursing responsibilities during the assessment of fetal health include preparing the patient properly, explaining the reason for the test, and clarifying and interpreting results in collaboration with other health care providers. The nurse can provide the psychosocial support that will allay or reduce parental anxiety. Figure 5-1 shows amniocentesis, and Table 5-1 reviews common diagnostic tests that assess the status of the fetus. Fetal assessment techniques used during labor are discussed in Chapter 6.

Table 5-1

| TEST | DESCRIPTION | USE(S) DURING PREGNANCY |

| Ultrasound examination | Visualize a gestational sac in early pregnancy to confirm the pregnancy. Identify site of implantation (uterine or ectopic). Verify fetal viability or death. Identify a multifetal pregnancy, such as twins or triplets. Diagnose some fetal structural abnormalities. Determine gestational age of the embryo or fetus. Determine the amount of amniotic fluid. | |

| Amniotic fluid volume (AFV) | This ultrasound scan measures the amniotic fluid pockets in all four quadrants surrounding the mother’s umbilicus and produces an amniotic fluid index (AFI). | From 5-19 cm is considered normal; <5 cm is known as oligohydramnios (insufficient amniotic fluid) and is associated with growth restriction and fetal distress during labor because of “kinking” of the cord. A measurement >30 cm is polyhydramnios (excess amniotic fluid) and is associated with neural tube defects, gastrointestinal obstruction, and fetal hydrops. |

| Estimation of gestational age | This ultrasound examination at 8 weeks of gestation can measure the gestational sac. | Between 7 and 14 weeks the crown-rump length can indicate fetal age. After 12 weeks the biparietal diameter of the fetus and the femur length give an accurate estimation of fetal age. The biparietal diameter of the fetus at 36 weeks is 8.7 cm, and at term it is 9.8 cm. |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | This imaging technique provides a noninvasive radiological view of fetal structures, including the placenta. | Used when there is a high suspicion of an anomaly. |

| Kick count | Maternal assessment of fetal movement | Fewer than three fetal kicks within an hour or cessation of fetal movement for 12 hours indicates the need for evaluation. A daily fetal movement record is kept at home once a day, and the findings are evaluated during prenatal visits to ensure fetal health. The sleep cycle of the fetus should be considered when selecting a time to evaluate fetal movement. |

| Doppler ultrasound blood flow assessment | This assessment uses high-frequency sound waves to study the flow of blood through vessels. | Determine adequacy of blood flow through the placenta and umbilical cord vessels in women in whom it is likely to be impaired (such as those with pregnancy-induced hypertension or diabetes mellitus). |

| Alpha-fetoprotein testing (AFP) | Test determines the level of this fetal protein in the pregnant woman’s serum or in a sample of amniotic fluid; correct interpretation requires an accurate gestational age. | |

| Chorionic villus sampling | Sampling consists of obtaining a small part of the developing placenta to analyze fetal cells at 10-12 weeks of gestation. | Identify chromosome abnormalities or other defects that can be determined by analysis of cells. Results of chromosome studies are available 24-48 hours later. Cannot be used to determine spina bifida or anencephaly (see AFP testing). Higher rate of spontaneous abortion after procedure than after amniocentesis. Reports of limb reduction defects in newborns. Rh0(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) is given to the Rh-negative woman. |

| Amniocentesis | This procedure consists of insertion of a thin needle through the abdominal and uterine walls to obtain a sample of amniotic fluid, which contains cast-off fetal cells and various other fetal products (see Figure 5-1). Standard genetic amniocentesis is done at 15-17 weeks of gestation; and early genetic amniocentesis is done at 11-14 weeks of gestation for some disorders. | |

| Non–stress test (NST) | Test comprises evaluation with an electronic fetal monitor of the fetal heart rate (FHR) for accelerations of at least 15 beats/min lasting 15 seconds in a 20-minute period. Fetal movements do not have to accompany the accelerations. | Identify fetal compromise in conditions associated with poor placenta function, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or postterm gestation. Adequate accelerations of the FHR are reassuring that the placenta is functioning properly and the fetus is well oxygenated. |

| Vibroacoustic stimulation test | This procedure is similar to the NST; in addition, an artificial larynx device is used to stimulate the fetus with sound. Expected response is acceleration of the FHR, as in the NST. | |

| Contraction stress test (CST) | Test is an evaluation of the FHR response to mild uterine contractions by using an electronic fetal monitor; contractions may be induced by self-stimulation of the nipples, which causes the woman’s pituitary gland to release oxytocin, or by intravenous oxytocin (Pitocin) infusion. The woman must have at least three contractions at least 40 seconds in duration in a 10-minute period for interpretation of the CST. | Purposes are the same as for the NST; the CST may be done if the NST results are nonreassuring (the fetal heart does not accelerate) or if they are questionable. Late decelerations after a contraction can indicate that fetus may not tolerate labor. Normal CST results mean there are no late decelerations and the fetus can probably tolerate labor. |

| Biophysical profile (BPP) | Profile consists of a group of five fetal assessments: fetal heart rate and reactivity (the NST), fetal breathing movements, fetal body movements, fetal tone (closure of the hand), and the volume of amniotic fluid (AFI). Some centers omit the NST, and others assess only the NST and AFI. | |

| Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling | Procedure serves to obtain a fetal blood sample from a placental vessel or from the umbilical cord; this may be used to give a blood transfusion to an anemic fetus. | |

| Tests of fetal lung maturity: | These tests use a sample of amniotic fluid (obtained by amniocentesis or from the pool of fluid in the vagina) to determine substances that indicate fetal lungs are mature enough to adapt to extrauterine life | Evaluate whether the fetus is likely to have respiratory complications in adapting to extrauterine life. May be done to determine whether the fetal lungs are mature before performing an elective cesarean birth or inducing labor if the gestational age is questionable. Also used to evaluate whether the fetus should be promptly delivered or allowed to mature further when the membranes rupture and the gestation is at <37 weeks or if the gestation is questionable. |

| Lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio | A 2 : 1 ratio indicates fetal lung maturity (3 : 1 ratio desirable for diabetic mother); fluid usually obtained by amniocentesis | |

| Foam stability index (FSI, or “shake test”) |

The future of fetal assessment lies in the continued development of new ultrasound technologies and hand-held receivers. Ultrasound pictures taken by a portable instrument can be transmitted via the Internet to be interpreted by experts in medical centers. Telemedicine, a growing field, is a specialized technology in prenatal care.

Pregnancy-Related Complications

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Mild nausea and vomiting are easily managed during pregnancy (see Chapter 4). In contrast, the woman with hyperemesis gravidarum has excessive nausea and vomiting that can significantly interfere with her food intake and fluid balance. Fetal growth may be restricted, resulting in a low-birth-weight infant. Dehydration impairs perfusion of the placenta, reducing the delivery of blood oxygen and nutrients to the fetus.

Manifestations.

Hyperemesis gravidarum differs from “morning sickness” of pregnancy in one or more of the following ways:

Treatment.

The health care provider will rule out other causes for the excessive nausea and vomiting, such as gastroenteritis or liver, gallbladder, or pancreatic disorders, before making this diagnosis. The medical treatment for hyperemesis gravidarum is to correct dehydration and electrolyte or acid-base imbalances with oral or intravenous fluids. Antiemetic drugs may be prescribed after the health care provider informs the woman about any potential risk to the developing fetus. Occasionally, severe cases necessitate total parenteral nutrition. The woman may need hospital admission to correct dehydration and inadequate nutrition if home measures are not successful. The condition is self-limiting in most women, although it is quite distressing to the woman and her family.

Nursing Care.

Nursing care focuses on patient teaching, because most care occurs in the home. The woman should be taught how to reduce factors that trigger nausea and vomiting. She should avoid food odors, which may abound in meal preparation areas and tray carts if she is hospitalized. If she becomes nauseated when her food is served, the tray should be removed promptly and offered again later.

Accurate intake and output records are kept to assess fluid balance. Frequent, small amounts of food and fluid keep the stomach from becoming too full, which can trigger vomiting. Easily digested carbohydrates, such as crackers or baked potatoes, are tolerated best. Foods with strong odors should be eliminated from the diet. Taking liquids between solid meals helps to reduce gastric distention. Sitting upright after meals reduces gastric reflux (backflow) into the esophagus.

The emesis basin is kept out of sight so that it is not a visual reminder of vomiting. It should be emptied at once if the woman vomits and the amount documented on the intake and output record.

Stress may contribute to hyperemesis gravidarum; stress may also result from this complication. The nurse should provide support by listening to the woman’s feelings about pregnancy, child rearing, and living with constant nausea. Although psychological factors may play a role in some cases of hyperemesis gravidarum, the nurse should not assume that every woman with this complication is adjusting poorly to her pregnancy.

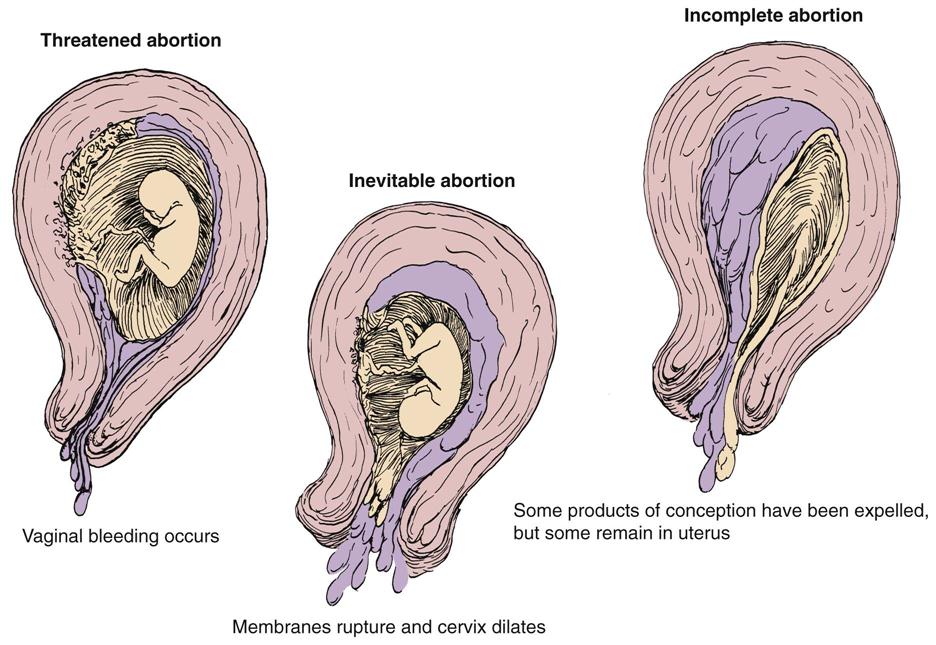

Bleeding Disorders of Early Pregnancy

Several bleeding disorders can complicate early pregnancy, such as spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) (Figure 5-2), ectopic pregnancy (see Figure 5-3), or hydatidiform mole (see Figure 5-4). Maternal blood loss decreases the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, resulting in fetal hypoxia, and places the fetus at risk.

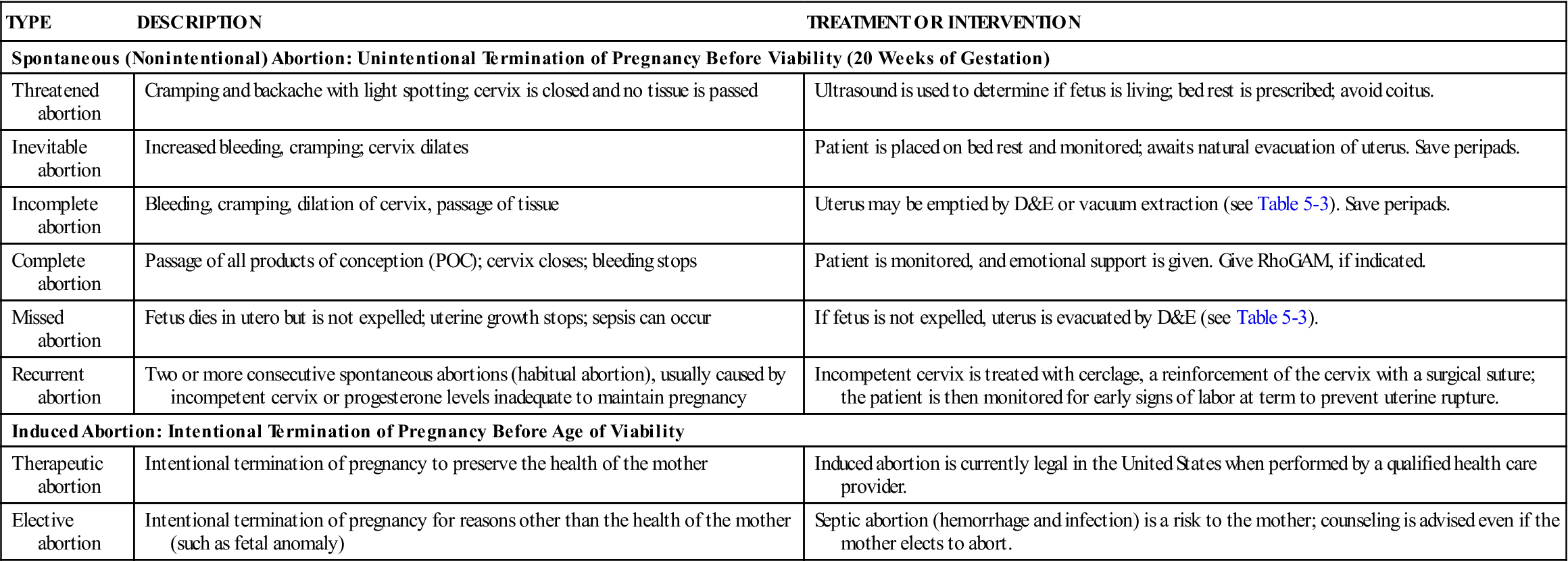

Abortion

Table 5-2 differentiates types of abortions.

Table 5-2

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | TREATMENT OR INTERVENTION |

| Spontaneous (Nonintentional) Abortion: Unintentional Termination of Pregnancy Before Viability (20 Weeks of Gestation) | ||

| Threatened abortion | Cramping and backache with light spotting; cervix is closed and no tissue is passed | Ultrasound is used to determine if fetus is living; bed rest is prescribed; avoid coitus. |

| Inevitable abortion | Increased bleeding, cramping; cervix dilates | Patient is placed on bed rest and monitored; awaits natural evacuation of uterus. Save peripads. |

| Incomplete abortion | Bleeding, cramping, dilation of cervix, passage of tissue | Uterus may be emptied by D&E or vacuum extraction (see Table 5-3). Save peripads. |

| Complete abortion | Passage of all products of conception (POC); cervix closes; bleeding stops | Patient is monitored, and emotional support is given. Give RhoGAM, if indicated. |

| Missed abortion | Fetus dies in utero but is not expelled; uterine growth stops; sepsis can occur | If fetus is not expelled, uterus is evacuated by D&E (see Table 5-3). |

| Recurrent abortion | Two or more consecutive spontaneous abortions (habitual abortion), usually caused by incompetent cervix or progesterone levels inadequate to maintain pregnancy | Incompetent cervix is treated with cerclage, a reinforcement of the cervix with a surgical suture; the patient is then monitored for early signs of labor at term to prevent uterine rupture. |

| Induced Abortion: Intentional Termination of Pregnancy Before Age of Viability | ||

| Therapeutic abortion | Intentional termination of pregnancy to preserve the health of the mother | Induced abortion is currently legal in the United States when performed by a qualified health care provider. |

| Elective abortion | Intentional termination of pregnancy for reasons other than the health of the mother (such as fetal anomaly) | Septic abortion (hemorrhage and infection) is a risk to the mother; counseling is advised even if the mother elects to abort. |

Treatment.

Abortion is the spontaneous (miscarriage) or intentional termination of a pregnancy before the age of viability (20 weeks of gestation) (see Table 5-2). When a threatened abortion occurs, efforts are made to keep the fetus in utero until the age of viability. In recurrent pregnancy loss, causes are investigated that could include genetic, immunological, anatomical, endocrine, or infectious factors. Cerclage, or suturing an incompetent cervix that opens when the growing fetus presses against it, is successful in most cases. A low human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level or low fetal heart rate by 8 weeks of gestation may be an ominous sign.

Termination of pregnancy after 20 weeks of gestation (age of viability) is called preterm labor and is discussed in Chapter 8. Table 5-3 describes procedures used in pregnancy termination. In all cases of pregnancy loss, counseling of the parent(s) is essential. Even when the mother elects to terminate pregnancy, there are emotional responses that should be recognized and addressed.

Table 5-3

Procedures Used in Pregnancy Termination

| PROCEDURE AND DESCRIPTION | COMMENTS |

| Vacuum aspiration (vacuum curettage): Cervical dilation with metal rods or laminaria (a substance that absorbs water and swells, thus enlarging the cervical opening) followed by controlled suction through a plastic cannula to remove all products of conception (POC) | Used for first-trimester abortions; also used to remove remaining POC after spontaneous abortion; may be followed by curettage (see Dilation and evacuation); paracervical block (local anesthesia of the cervix) or general anesthesia needed; conscious sedation with midazolam (Versed) may be used. |

| Dilation and evacuation (D&E): Dilation of the cervix as in vacuum curettage followed by gentle scraping of the uterine walls to remove POC | Used for first-trimester abortions and to remove all POC after a spontaneous abortion; greater risk of cervical or uterine trauma and excessive blood loss than with vacuum curettage; paracervical block or general anesthesia needed. |

| Mifepristone (RU486) | An oral medication that may be taken until up to 5 weeks of gestation; often used with a prostaglandin agent that causes bleeding and termination of pregnancy within 5 days. |

| Methotrexate | An oral or intramuscular medication given with misoprostol, a prostaglandin analog; applied intravaginally, causes termination of pregnancy within 1 or 2 days. |

| Prostaglandins | Available in gel form or intrauterine injection; can be used in the second trimester to terminate pregnancy; unpleasant side effects can occur. |

| Hypertonic uterine infusion | Causes uterine contractions to occur within 12-24 hours; in early second trimester, drugs such as misoprostol (Cytotec) and oxytocin expedite the process; complications include sepsis and bleeding. |

Oxytocin (Pitocin) controls blood loss before and after curettage, much as the drugs do after term birth. Rh0(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM [300 mcg] or the lower-dose MICRhoGAM [50 mcg]) is given to Rh-negative women after any abortion to prevent the development of antibodies that might harm the fetus during a subsequent pregnancy.

Nursing Care

Physical care.

The nurse documents the amount and character of bleeding and saves anything that looks like clots or tissue for evaluation by a pathologist. A pad count and an estimate of how saturated each is (e.g., 50%, 75%) documents blood loss most accurately. The woman with threatened abortion who remains at home is taught to report increased bleeding or passage of tissue.

The nurse should check the hospitalized woman’s bleeding and vital signs to identify hypovolemic shock resulting from blood loss. She should not eat (remain NPO) if she has active bleeding to prevent aspiration if anesthesia is required for dilation and evacuation (D&E) treatment. Laboratory tests, such as a hemoglobin level and hematocrit, are ordered.

After vacuum aspiration or curettage, the amount of vaginal bleeding is observed. The blood pressure, pulse, and respirations are checked every 15 minutes for 1 hour, then every 30 minutes until discharge from the postanesthesia care unit. The mother’s temperature is checked on admission to the recovery area and every 4 hours until discharge to monitor for infection.

Most women are discharged directly from the recovery unit to their home after curettage. Guidelines for self-care at home include the following:

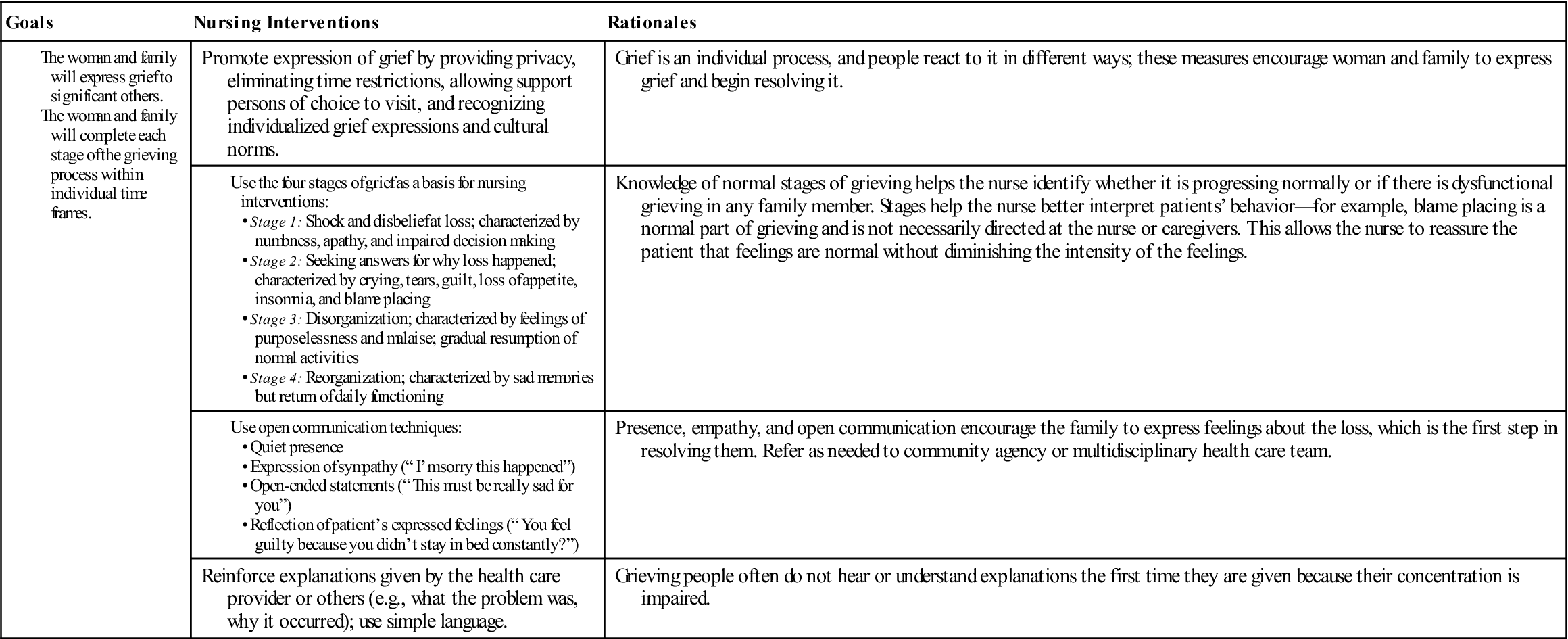

Emotional care.

Society often underestimates the emotional distress spontaneous abortion causes the woman and her family. Even if the pregnancy was not planned or not suspected, they often grieve for what might have been. Their grief may last longer and be deeper than they or other people expect. The nurse listens to the woman and acknowledges the grief she and her partner feel. The Communication box gives examples of effective and ineffective techniques for communicating with the family experiencing pregnancy loss. Spiritual support of the family’s choice and community support groups may help the family work through the grief of any pregnancy loss. Nursing Care Plan 5-1 suggests interventions for families experiencing early pregnancy loss.

Ectopic Pregnancy

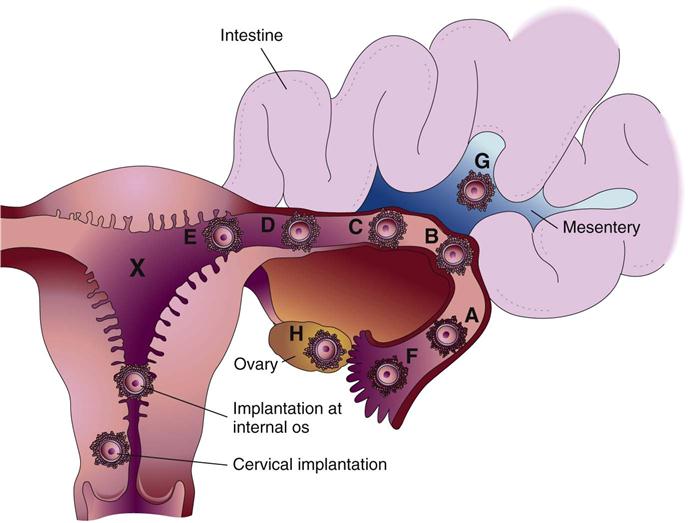

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilized ovum (zygote) is implanted outside the uterine cavity (Figure 5-3). Of all ectopic pregnancies, 95% occur in the fallopian tube (tubal pregnancy). An obstruction or other abnormality of the tube prevents the zygote from being transported into the uterus. Scarring or deformity of the fallopian tubes or inhibition of normal tubal motion to propel the zygote into the uterus may result from the following:

Use of an intrauterine device for contraception may contribute to ectopic pregnancy, because these devices promote inflammation within the uterus. A woman who has had a previous tubal pregnancy or a failed tubal ligation is also more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy.

A zygote that is implanted in a fallopian tube cannot survive for long because the blood supply and size of the tube are inadequate. The zygote or embryo may die and be resorbed by the woman’s body, or the tube may rupture with bleeding into the abdominal cavity, creating a surgical emergency.

Manifestations.

The woman often complains of lower abdominal pain, sometimes accompanied by light vaginal bleeding. If the tube ruptures, she may have sudden severe lower abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and signs of hypovolemic shock (Box 5-1). The amount of vaginal bleeding may be minimal because most blood is lost into the abdomen rather than externally through the vagina. Shoulder pain is a symptom that often accompanies bleeding into the abdomen (referred pain).

Treatment.

A sensitive pregnancy test for hCG is done to determine if the woman is pregnant. Trans-vaginal ultrasound examination determines whether the embryo is growing within the uterine cavity. Culdocentesis (puncture of the upper posterior vaginal wall with removal of peritoneal fluid) may occasionally be done to identify blood in the woman’s pelvis, which suggests tubal rupture. A laparoscopic examination may be done to view the damaged tube with an endoscope (lighted instrument for viewing internal organs).

The physician attempts to preserve the tube if the woman wants other children, but this is not always possible. The priority medical treatment is to control blood loss. Blood transfusion may be required for massive hemorrhage. One of the following three courses of treatment is chosen, depending on the gestation and the amount of damage to the fallopian tube:

Nursing Care.

Nursing care includes observing for hypovolemic shock as in spontaneous abortion. Vaginal bleeding is assessed, although most lost blood may remain in the abdomen. The nurse should report increasing pain, particularly shoulder pain, to the physician.

If the woman has surgery, preoperative and postoperative care is similar to that for other abdominal surgery, as follows:

• Measurement of vital signs to identify hypovolemic shock; of temperature to identify infection

• Assessment of lung and bowel sounds

• Intravenous fluid; blood replacement may be ordered if the loss was substantial

• Pain medication, often with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) after surgery

In addition to physical preoperative and postoperative care, the nurse provides emotional support because the woman and her family may experience grieving similar to that accompanying spontaneous abortion. Loss of a fallopian tube threatens future fertility and is another source of grief.

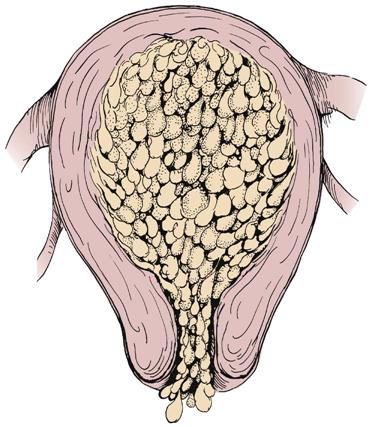

Hydatidiform Mole

Hydatidiform mole (gestational trophoblastic disease; also known as a molar pregnancy) occurs when the chorionic villi (fringelike structures that form the placenta) increase abnormally and develop vesicles (small sacs) that resemble tiny grapes (Figure 5-4). The mole may be complete, with no fetus present, or partial, in which only part of the placenta has the characteristic vesicles. Hydatidiform mole may cause hemorrhage, clotting abnormalities, hypertension, and later development of cancer (choriocarcinoma). Chromosome abnormalities are found in many cases of hydatidiform mole. It is more likely to occur in women at the age extremes of reproductive life, and a woman who has had one molar pregnancy has a 1% chance of another molar pregnancy in the future.

Manifestations.

Signs associated with hydatidiform mole appear early in pregnancy and can include the following:

• Bleeding, which may range from spotting to profuse hemorrhage; cramping may be present

• Rapid uterine growth and a uterine size that is larger than expected for the gestation

• Failure to detect fetal heart activity

• Signs of hyperemesis gravidarum (see p. 79)

• Unusually early development of gestational hypertension (see p. 90)

• Higher than expected levels of hCG

• A distinctive “snowstorm” pattern on ultrasound but no evidence of a developing fetus in the uterus

Treatment.

The uterus is evacuated by vacuum aspiration and D&E. The level of hCG is tested and retested until it is undetectable, and the levels are followed for at least 1 year. Persistent or rising levels suggest that vesicles remain or that malignant change has occurred. The woman should delay conceiving until follow-up care is complete because a new pregnancy would confuse tests for hCG. Rho(D) immune globulin is prescribed for the Rh-negative woman.

Nursing Care.

The nurse observes for bleeding and shock; care is similar to that given in spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy. If the woman also experiences hyperemesis or preeclampsia, the nurse incorporates care related to those conditions as well. The woman has also lost a pregnancy, so the nurse should provide care related to grieving, similar to that for a spontaneous abortion. The need to delay another pregnancy may be a concern if the woman is nearing the end of her reproductive life and wants a child; therefore the need for follow-up examinations is reinforced. The woman is encouraged and taught how to use contraception (see Chapter 11).

Bleeding Disorders of Late Pregnancy

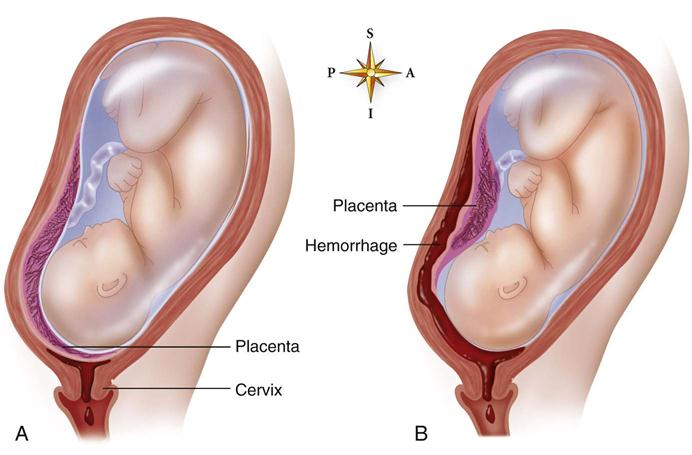

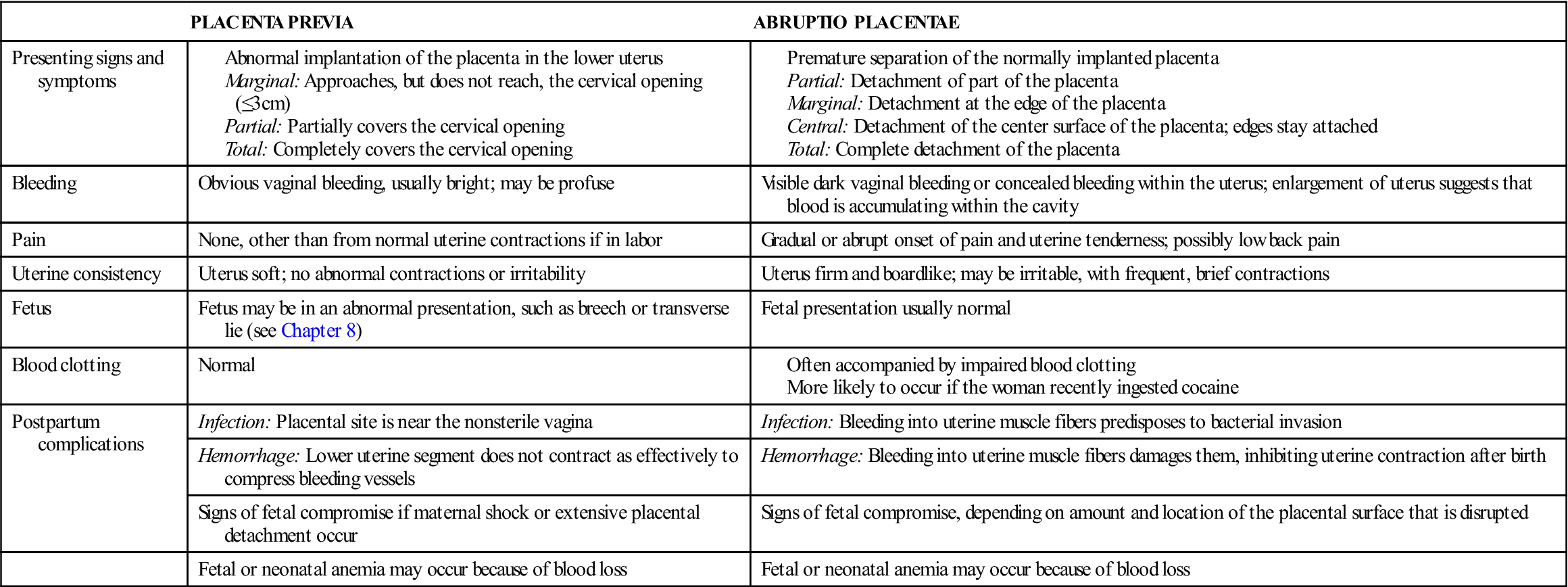

Bleeding in late pregnancy is often caused by placenta previa or abruptio placentae (Table 5-4).

Table 5-4

Comparison of Placenta Previa and Abruptio Placentae

| PLACENTA PREVIA | ABRUPTIO PLACENTAE | |

| Presenting signs and symptoms | ||

| Bleeding | Obvious vaginal bleeding, usually bright; may be profuse | Visible dark vaginal bleeding or concealed bleeding within the uterus; enlargement of uterus suggests that blood is accumulating within the cavity |

| Pain | None, other than from normal uterine contractions if in labor | Gradual or abrupt onset of pain and uterine tenderness; possibly low back pain |

| Uterine consistency | Uterus soft; no abnormal contractions or irritability | Uterus firm and boardlike; may be irritable, with frequent, brief contractions |

| Fetus | Fetus may be in an abnormal presentation, such as breech or transverse lie (see Chapter 8) | Fetal presentation usually normal |

| Blood clotting | Normal | |

| Postpartum complications | Infection: Placental site is near the nonsterile vagina | Infection: Bleeding into uterine muscle fibers predisposes to bacterial invasion |

| Hemorrhage: Lower uterine segment does not contract as effectively to compress bleeding vessels | Hemorrhage: Bleeding into uterine muscle fibers damages them, inhibiting uterine contraction after birth | |

| Signs of fetal compromise if maternal shock or extensive placental detachment occur | Signs of fetal compromise, depending on amount and location of the placental surface that is disrupted | |

| Fetal or neonatal anemia may occur because of blood loss | Fetal or neonatal anemia may occur because of blood loss |

Placenta Previa

Placenta previa occurs when the placenta develops in the lower part of the uterus rather than the upper. There are three degrees of placenta previa, depending on the location of the placenta in relation to the cervix (Figure 5-5, A), as follows:

Marginal: Placenta reaches within 2 to 3 cm of the cervical opening

Partial: Placenta partly covers the cervical opening

A low-lying placenta is implanted near the cervix but does not cover any of the opening. This variation is not a true placenta previa and may or may not be accompanied by bleeding. The low-lying placenta may be discovered during a routine ultrasound examination in early pregnancy. It also may be diagnosed during late pregnancy because the woman has signs similar to those of a true placenta previa.

Manifestations.

Painless vaginal bleeding, usually bright red, is the main characteristic of placenta previa. The woman’s risk of hemorrhage increases as term approaches and the cervix begins to efface (thin) and dilate (open). These normal prelabor changes disrupt the placental attachment. The fetus is often in an abnormal presentation (e.g., breech or transverse lie) because the placenta occupies the lower uterus, which often prevents the fetus from assuming the normal head-down presentation.

The fetus or neonate may have anemia or hypovolemic shock because some of the blood lost may be fetal blood. Fetal hypoxia may occur if a large disruption of the placental surface reduces the transfer of oxygen and nutrients.

The woman with placenta previa is more likely than others to have an infection or hemorrhage after birth for the following reasons:

Treatment.

Medical care depends on the length of gestation and the amount of bleeding. The goal is to maintain the pregnancy until the fetal lungs are mature enough that respiratory distress is less likely (at about 34 weeks of gestation). Delivery will be done if bleeding is sufficient to jeopardize the mother or fetus, regardless of gestational age.

The woman should lie on her side or have a pillow under one hip to avoid supine hypotension. If bleeding is extensive or the gestation is near term, a cesarean section is performed for partial or total placenta previa. The woman with a low-lying placenta or marginal placenta previa may be able to deliver vaginally unless the blood loss is excessive.

Nursing Care.

The priorities of nursing care include observation of vaginal blood loss and of signs and symptoms of shock. Vital signs are taken every 15 minutes if the woman is actively bleeding, and oxygen is often given to increase the amount delivered to the fetus. Vaginal examination is not done because it may precipitate bleeding if the placental attachment is disrupted. The fetal heart rate is monitored continuously. The nurse implements care for a cesarean delivery, as needed (see Chapter 8). The parents of the infant are often fearful for their child, particularly if a preterm delivery is required. Supportive care should be given.

Abruptio Placentae

Abruptio placentae is the premature separation of a placenta that is normally implanted. Predisposing factors include the following:

• Cigarette smoking and poor nutrition

• Blows to the abdomen, such as might occur in battering or accidental trauma

• Prior history of abruptio placentae

Abruptio placentae may be partial or total (see Figure 5-5, B); it may be marginal (separating at the edges) or central (separating in the middle). Bleeding may be visible or concealed behind the partially attached placenta.

Manifestations.

Bleeding accompanied by abdominal or low back pain is the typical characteristic of abruptio placentae. Unlike the bleeding in placenta previa, most or all of the bleeding may be concealed behind the placenta. Obvious dark-red vaginal bleeding occurs when blood leaks past the edge of the placenta. The woman’s uterus is tender and unusually firm (boardlike) because blood leaks into its muscle fibers. Frequent, cramplike uterine contractions often occur (uterine irritability).

The fetus may or may not have problems, depending on how much placental surface is disrupted. As in placenta previa, some of the blood lost may be fetal, and the fetus or neonate may have anemia or hypovolemic shock.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a complex disorder that may complicate abruptio placentae. The large blood clot that forms behind the placenta consumes clotting factors, which leaves the rest of the mother’s body deficient in these factors. Clot formation and anticoagulation (destruction of clots) occur simultaneously throughout the body in the woman with DIC. She may bleed from her mouth, nose, incisions, or venipuncture sites because the clotting factors are depleted.

Postpartum hemorrhage may also occur because the injured uterine muscle does not contract effectively to control blood loss. Infection is more likely to occur because the damaged tissue is susceptible to microbial invasion.

Treatment.

The treatment of choice, immediate cesarean delivery, is done because of the risk for maternal shock, clotting disorders, and fetal death. Blood and clotting factor replacement may be needed because of DIC. The mother’s clotting action quickly returns to normal after birth because the source of the abnormality is removed.

Nursing Care.

Preparation for cesarean section and close monitoring of vital signs and fetal heart are essential. Signs of shock and bleeding from the nose, the gums, or other unexpected sites should be promptly reported. Rapid increase in the size of the uterus suggests that blood is accumulating within it. The uterus is usually very tender and hard. Nursing care after delivery is similar to that with placenta previa.

The fetus sometimes dies before delivery. See Nursing Care Plan 5-1 for nursing care related to fetal death (stillbirth) and support of the grieving family. Many therapeutic communication techniques outlined in the Communication box on p. 85 are appropriate. The care of a pregnant woman with excessive bleeding is summarized in Box 5-2.

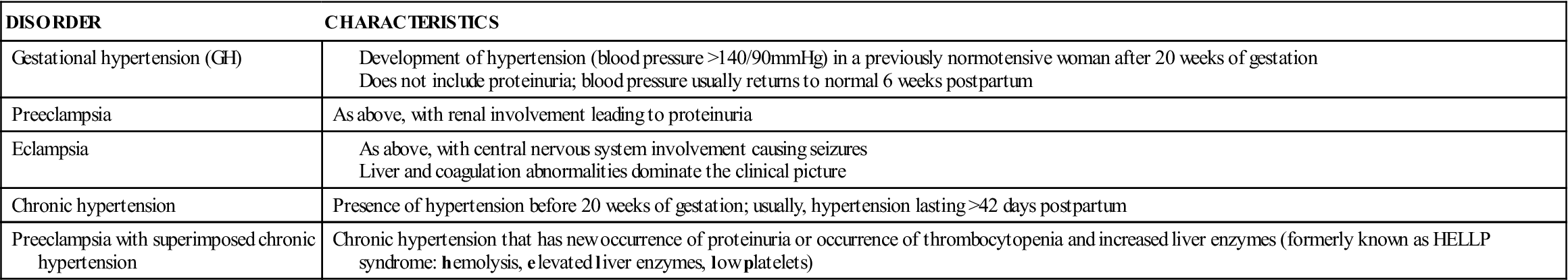

Hypertension During Pregnancy

Hypertension may exist before pregnancy (chronic hypertension), but often it develops as a pregnancy complication (gestational hypertension [GH], formerly known as pregnancy-induced hypertension [PIH]). Table 5-5 compares the different types of hypertension during pregnancy. The term preeclampsia may be used when GH includes proteinuria. Preeclampsia progresses to eclampsia when convulsions occur. One sometimes hears the term toxemia, an old term for GH.

Table 5-5

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Modified from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2006). Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin #33, Washington, DC; and National Institutes of Health, 2001.

The cause of GH is unknown, but birth is its cure. It usually develops after the twentieth week of gestation. Vasospasm (spasm of the arteries) is the main characteristic of GH. Although the cause is unknown, any of several risk factors increases a woman’s chance of developing GH (Box 5-3).

There has been a gradual increase in the number of women delaying pregnancy until over age 30 years, and the chances of chronic hypertension complicating pregnancy has increased. Chronic hypertension is considered moderate if the systolic reading is between 140 and 160 mm Hg and the diastolic reading is below 110 mm Hg. However, an increase over baseline blood pressure of 30 mm Hg or more systolic and 15 mm Hg diastolic will place the woman in a high-risk category. Therefore a woman with a baseline blood pressure that is normally low, such as 90/60 mm Hg, may be at risk for GH if her blood pressure rises to 120/80 mm Hg (Creasy et al., 2009). Blood pressure normally decreases during the first two trimesters.

Hypertension is closely related to the development of complications, such as abruptio placentae, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, prematurity, and stillbirth, so special care of the pregnant woman with hypertension is essential. The approach to chronic hypertension during pregnancy is complex because many drugs used to treat hypertension, such as atenolol, cause a drop in mean arterial blood pressure and can result in restricted fetal growth and other problems. For this reason, antihypertensive medication is not given for mild to moderate levels of high blood pressure. Instead, frequent prenatal visits, urinalysis to detect proteinuria, and fetal assessments are the standards of care, and medication is started if the blood pressure exceeds the moderate range. Drugs of choice include methyldopa (Aldomet), alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic blockers (labetalol), and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine) in some cases of hypertensive crisis.

Manifestations of Gestational Hypertension.

Vasospasm impedes blood flow to the mother’s organs and placenta, resulting in one or more of these signs: (1) hypertension, (2) edema, and (3) proteinuria (protein in the urine). Severe GH can also affect the central nervous system, eyes, urinary tract, liver, gastrointestinal system, and blood clotting function. Table 5-6 summarizes laboratory tests that aid in diagnosis.

Table 5-6

Laboratory Tests for Patients with Gestational Hypertension

| TEST | RATIONALE |

| Hemoglobin and hematocrit | Detects hemoconcentration for indication of severity of gestational hypertension (GH) |

| Platelets | Thrombocytopenia suggests GH |

| Urine for protein | Proteinuria confirms GH when hypotension is present |

| Serum creatinine | Elevated creatinine and oliguria suggest GH |

| Serum uric acid | Elevated uric acid suggests GH |

| Serum transaminase | Elevated transaminase confirms liver involvement in GH |

Modified from National High Blood Pressure Education Program. (2001). Working group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynecology, 46(2), 22.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree