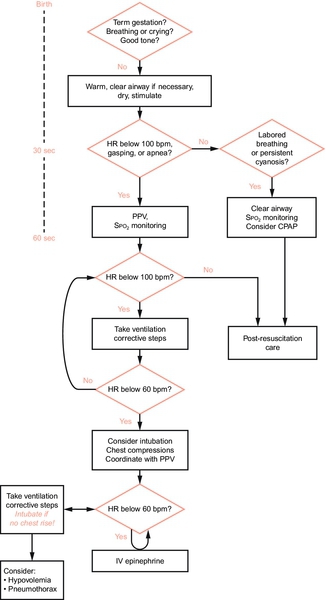

CHAPTER 5 Barbara Elizabeth Pappas; Deanna Lynn Robey 2. Compare three physiologic characteristics of the neonate that make neonatal resuscitation different from adult resuscitation. 3. List three antepartum and intrapartum factors that indicate the neonate may be at risk for developing asphyxia. 4. Identify the equipment needed for neonatal resuscitation. 5. Review the components of neonatal resuscitation as outlined by the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) of the American Heart Association/American Academy of Pediatrics. 6. Recognize three neonatal disease states, congenital malformations, or special situations that may alter the resuscitation process. 7. Describe three potential complications of neonatal resuscitation. 8. Discuss the postresuscitative needs of the neonate. 9. Verbalize three risk factors that may leave the neonate at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest after the initial period of stabilization. 10. Discuss ethical considerations surrounding resuscitation of periviable or marginally viable neonates or those with unpredictable life expectancy. Few neonates require resuscitation at birth. Approximately 10% of all newborn infants require some assistance at birth, but less than 1% require full resuscitative measures (Perlman et al., 2010). Most neonates only require basic stabilization, including thermal and airway management. Neonates requiring more advanced resuscitation often have respiratory insufficiency or depression. Neonates at risk for resuscitation benefit from prompt, organized, and efficient interventions tailored to their needs and response. High-functioning resuscitation teams are optimal. Formalized education, hands-on experience with equipment, periodic review, and mock codes are all beneficial in promoting the resuscitation skills necessary for a smooth and coordinated resuscitation. The risk for cardiopulmonary arrest does not stop once the neonate leaves the delivery environment. Physical and physiologic vulnerabilities continue to place the neonate at risk. Prevention is key, and although studies regarding neonatal rapid response teams are not available, rapid response teams should be considered as an avenue to reduce the need for resuscitation in the neonatal period. Newly born: time of the infant’s life from birth to the first hours after birth. Neonate: refers to the first 28 days of the infant’s life. Infant: neonatal period extending through the first 12 months of life. 1. Large head in proportion to body size. At risk for: a. Insensible water loss (IWL). b. Heat loss: no insulating fat layer. c. Minimal insulation and moisture retention from hair. 2. Large surface area/body size ratio. At risk for: b. Heat loss. 3. Decreased muscle mass. At risk for: a. Increased potential for heat loss through external gradient. b. Decreased ability to flex body to conserve heat, causing increased surface area in premature or ill neonate. c. Decreased ability to generate heat. 4. Decreased subcutaneous fat (premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction). At risk for: a. Decreased heat production (from brown fat metabolism). b. Increased heat loss (from lack of insulation and decreased flexion). 5. Thinner epidermal layer. At risk for: a. Increased IWL; the more premature, the greater the loss. b. Decreased support of internal gradient to maintain heat. c. Increased risk for breakdown and injury can contribute to increased IWL. 6. Immature systems. b. Neuromuscular system: decreased ability to shiver and generate heat. c. Liver: ability to metabolize drugs and mobilize glucose stores is decreased. d. Kidneys: risk for decreased perfusion with compromise; ability to excrete drugs and fluids is impaired. e. Gastrointestinal tract: gastric distention and respiratory compromise related to decreased gastrointestinal motility and forced air entry with bag-and-mask ventilation. f. Metabolism: decreased stores, decreased ability to convert stored glucose, inefficient energy production from stored glucose, and increased utilization of glucose result in hypoglycemia. g. Respiratory system: decreased absorption of lung fluid if cesarean section without trial of labor, decreased surface area for gas exchange, decreased availability of surfactant, and increased risk for aspiration from gastric distention. h. Immune system: increased predisposition to infection, immature immune response despite adequate cell counts. 7. Glottis positioned anteriorly in the hypopharynx. a. Intubation may be difficult. b. The neonate is predisposed to airway compromise from positioning. 8. Short neck. a. Lack of clarity in identifying landmarks contributes to difficulty in intubation. b. Tendency for hyperextension and flexion of neck. 9. Preferential nasal breathing. a. Preferential nose breather; patency is essential to airway maintenance. b. Anatomic patency must be confirmed. c. Increased airway resistance with edema from nasal suctioning. 10. Venous access. a. Small and superficial veins: access is difficult, vessels fragile. b. Vasoconstriction associated with acidosis, hypothermia, hypoglycemia, and shock. c. Umbilical access. Normal cord includes two arteries and one vein. Inadvertent cannulization of the portal vein with umbilical vein catheterization can lead to liver damage with chemical resuscitation. 11. Unknown physical variations make resuscitation and stabilization challenging. a. Lack of adequate perinatal information (i.e., ultrasound, genetic testing). b. Gross physical assessment only. Risk factors are warning signs that alert the perinatal team to the possibility of a crisis and the need for anticipatory preparation of neonatal resuscitation. 1. Maternal age less than 16 years or more than 35 years. 2. Maternal diabetes. 3. Hemorrhage, anemia. 4. Maternal substance abuse. 5. Maternal drug therapy such as magnesium sulfate, adrenergic blocking agents, over-the-counter or herbal medications. 6. Maternal infection. 7. No or late entry to prenatal care. 8. Polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios. 9. Maternal cardiac, renal, pulmonary, thyroid, endocrine, gastrointestinal, or neurologic disease. 10. Premature rupture of membranes. 11. Anatomic abnormalities of the uterus. 12. Isoimmunization, Rh, or ABO (blood group) incompatibilities. 13. Hypertension (pregnancy-induced hypertension, chronic). 14. Multiple gestation. 15. Post-term gestation. 16. Discrepancy in size and dates. 17. Previous pregnancy complication or fetal loss. 18. Diminished or absent fetal activity. 19. Fetal malformations or anomalies (i.e., fetal hydrops). B. Intrapartum period: conditions that predispose the fetus to difficult transition to extrauterine life or signs that the fetus is not tolerating the stresses of labor. Unsuccessful transition may ensue. 1. Abnormal fetal positioning or presentation (e.g., breech position). 2. Cesarean delivery. 3. Fetal heart rate abnormalities (e.g., bradycardia, tachycardia). 4. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns (category 2 or 3). 5. Maternal or fetal intrapartum blood loss (e.g., abruptio placentae, placenta previa). 6. Maternal sedation, anesthesia, or analgesia (e.g., narcotics in the previous 4 hours). 7. Maternal fever or infection (e.g., chorioamnionitis). 8. Prolonged labor (> 24 hours or second stage > 2 hours). 9. Premature labor. 10. Precipitous delivery. 11. Prolonged rupture of membranes (> 18 hours). 12. Prolapse of the umbilical cord. 13. Fetal malformations. 14. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid. 15. Uterine hyperstimulation and/or tachysystole with fetal heart rate pattern changes. 16. Instrument-assisted delivery (e.g., vacuum or forceps). 17. Macrosomia. C. Newly born period: signs or conditions in the delivery room or during the transitional period that indicate the neonate is having difficulty making all the physiologic changes needed for successful adaptation from intrauterine to extrauterine life. 2. Cardiac arrhythmia or murmur (e.g., tachycardia or bradycardia). 3. Extreme color change (e.g., cyanosis, plethora, pallor, mottling). 4. Prolonged or delayed capillary refill time. 5. Respiratory distress (e.g., apnea, tachypnea, grunting, altered breath sounds, excessive secretions). 6. Temperature instability. 7. Hypertonia/hypotonia. 8. Hypotension. 9. Seizures. 10. Hypoglycemia. 11. Prematurity. 12. Postmaturity. 13. Anemia or polycythemia. 14. Feeding difficulty or intolerance. 15. Seemingly well, then clinically deteriorates. Anticipation of and preparation for resuscitation require an evidence-based multidisciplinary approach. Internationally, the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) is recognized as the “gold standard” for neonatal resuscitation. Program content is based on the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association’s “Neonatal Resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care” (Kattwinkel et al., 2010). The Guidelines are based on the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (2010) Consensus on Science statement regarding treatment recommendations for neonatal resuscitation (Perlman et al., 2010). All units and facilities caring for newborn infants and neonates must be adequately staffed, prepared, and equipped to deliver resuscitative care when anticipated or unexpected resuscitation needs arise. A. Education and competency development. 2. Development and implementation of regular mock code system for education and quality improvement. 3. Annual competency evaluation and review are recommended. 4. Establish a quality improvement process for reviewing neonatal codes (e.g., effectiveness of call system, response times, and drug doses). B. General preparation. 2. Consider the development and utilization of a rapid response team. 3. Evaluate and update equipment frequently. 4. Arrange for periodic evaluation and maintenance of electrical equipment by the biomedical engineering department on a regularly scheduled basis. 5. Schedule periodic evaluation and maintenance of all respiratory equipment. 6. Formulate supply replacement procedures. Evaluate and replace supplies as quickly as possible after use (use equipment checklist). 7. Test alerting system for rapid, consistent response of personnel. C. Delivery room preparation. b. Promote effective communication between personnel, departments, and institutions that encourages identification and notification of high-risk situations and preparedness. 2. Prewarm room to minimize thermal losses in the newly born infant. Use a polyethylene plastic wrap or bag for neonate less than 29 weeks of gestation. 3. Assemble equipment in an organized, easily available system. Check function of equipment routinely and before use. 4. Ensure safety of team members and utilization of standard precautions. 5. Preheat warmer, hat, blankets, and nest (blanket rolls or bendable positioning device). Approximately 15 to 30 minutes (heat output set on high) is required to thoroughly warm the mattress on a radiant warmer bed. Assemble alternative heat sources (i.e., warming pad) at bedside as needed. 6. Identify and assemble available team members and designate roles. 7. Position resuscitation algorithms (Fig. 5-1) and charts easily within view of the resuscitative area. 8. Promote family-centered care through active family communication and involvement in decision making. D. Personnel roles. 2. Preparedness for resuscitation should exist at every delivery. Every delivery should be attended by at least one person skilled in neonatal resuscitation who is immediately available and solely responsible for initiating resuscitation and stabilization of the neonate. Additional qualified personnel should be available for more complex situations. For multiple births, separate teams for each baby should be present. 3. A family-centered approach should include a designated support and communication liaison to the family. Family support should not be left unassigned. Family presence during resuscitation has not been shown to be detrimental to the outcome of the neonate. E. Behavioral skills of resuscitative team. Teamwork, communication, and leadership are essential skills of a successful resuscitation. Team members may consist of a variety of provider levels, and experience working in stressful situations is critical. Key behavioral skills of an effective and efficient team include the following: 1. Knowledge of your environment. 2. Anticipation and planning. 3. Assuming leadership role. 4. Effective communication. 5. Optimal workload delegation. 6. Wise attention allocation. 7. Using all available information. 8. Using available resources. 9. Recruiting additional help when needed. 10. Professional behavior. F. Non–delivery room preparation. As with delivery room resuscitation, being prepared for unforeseen events throughout the infant’s entire hospitalization can facilitate success in a time of crisis. Unlike delivery room events, non–delivery room resuscitation is often unpredictable and risks ill preparedness. The following events may precipitate respiratory or circulatory compromise: 2. Choking or aspiration (i.e., feedings). 3. Unwitnessed cardiac arrest. 4. Seizure. 5. Hypoxia or airway obstruction. 6. Infection. 7. Postoperative period. 8. Air leak syndromes. 9. Severe anemia (i.e., subgaleal hemorrhage, abruption). 10. Shock. Not every item on the equipment list (Box 5-1) will be used, but it is important to have appropriate sizes and supply quantities to support a prolonged effort. Ensuring that equipment is functional and up to date is vital to a successful resuscitation. It is important that staff members be familiar with the equipment they will be using and practice with it frequently.

Neonatal Delivery Room Resuscitation

DEFINITIONS

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

RISK FACTORS

ANTICIPATION OF AND PREPARATION FOR RESUSCITATION

EQUIPMENT FOR NEONATAL RESUSCITATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree