Health Care and Fetal Assessment During Pregnancy

Objectives

2. Discuss the concept of preconception care.

3. Explain the significance of prenatal care.

4. Outline the care given during the initial prenatal visit.

5. Review care given on subsequent prenatal visits.

6. Explain five factors that place the fetus at risk.

7. Describe four methods of assessing the fetal condition during the antepartum period.

8. Explain the uses of ultrasonography during pregnancy.

9. Explain the uses of amniocentesis as a diagnostic tool.

10. Compare chorionic villi sampling with amniocentesis.

11. Explain the biophysical profile.

12. Describe the purpose of the nonstress test.

14. Demonstrate three exercises to strengthen and stretch muscles in preparation for childbirth.

15. Outline four safety precautions for exercising during pregnancy.

16. Discuss the benefits and limitations of immunizations during pregnancy.

17. Individualize various optimum weight gain patterns during pregnancy.

18. Identify the suggested dietary alterations during pregnancy.

19. Describe a common pica substance ingested by a pregnant woman.

20. Identify the basic philosophy of preparation for childbirth.

21. Illustrate three different breathing patterns used during labor and birth.

Key Terms

cleansing breath (p. 86)

doulas (DOO-lăz, p. 87)

effleurage (ĕf-loo-RĂZH, p. 85)

Kegel exercises (KĒ-gŭl, p. 69)

Lamaze technique (p. 84)

Leopold’s maneuvers (p. 64)

MyPlate (p. 81)

paced breathing (p. 86)

pelvic tilt exercise (p. 69)

pica (PĪ-kă, p. 84)

preconception care (p. 61)

Valsalva’s maneuver (văl-SĂL-văz, p. 87)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

Preconception Care

Preconception care is health care and screening conducted before pregnancy occurs so that medical risk factors or lifestyle behaviors can be identified, managed, or changed before conception. The normalcy of pregnancy is greatly influenced by prepregnancy health. Most women who seek medical care as soon as they realize they may be pregnant are already at or past 8 weeks’ gestation, which may be too late for some interventions to be effective. Most birth defects occur between 2 and 8 weeks’ gestation. These missed opportunities include ensuring an adequate daily intake of folic acid, updating immunization status, ceasing smoking, treating current infections, and obtaining genetic counseling or testing. Prenatal data collection includes physical, psychological, and psychosocial factors that will affect the health of the mother and fetus. This includes exposure to hazardous materials in the workplace. Ideally, prenatal care starts before pregnancy occurs. Preconception care is best achieved when a pregnancy is planned.

Prenatal Care

Early and regular prenatal care dramatically reduces infant and maternal morbidity and mortality and offers a unique opportunity for nurses to influence the family’s health. Early detection of potential problems leads to prompt assessment and treatment, which greatly improves the pregnancy outcome. Pregnancy is a normal process, and the primary focus is education for self-care. Pregnancy affects the mother’s body and the family’s integrity; therefore, the entire family is included in the care plan (Figure 5-1). The major goals of prenatal care are listed in Box 5-1.

Collaborative Care

To collaborate is to work together with others. Collaborative care involves the patient and the nurse with other members of the health care team contributing to the care plan for the woman. The nurse, along with other multidisciplinary health team members, can tailor interventions to meet specific needs of the patient and family.

Cultural Competence

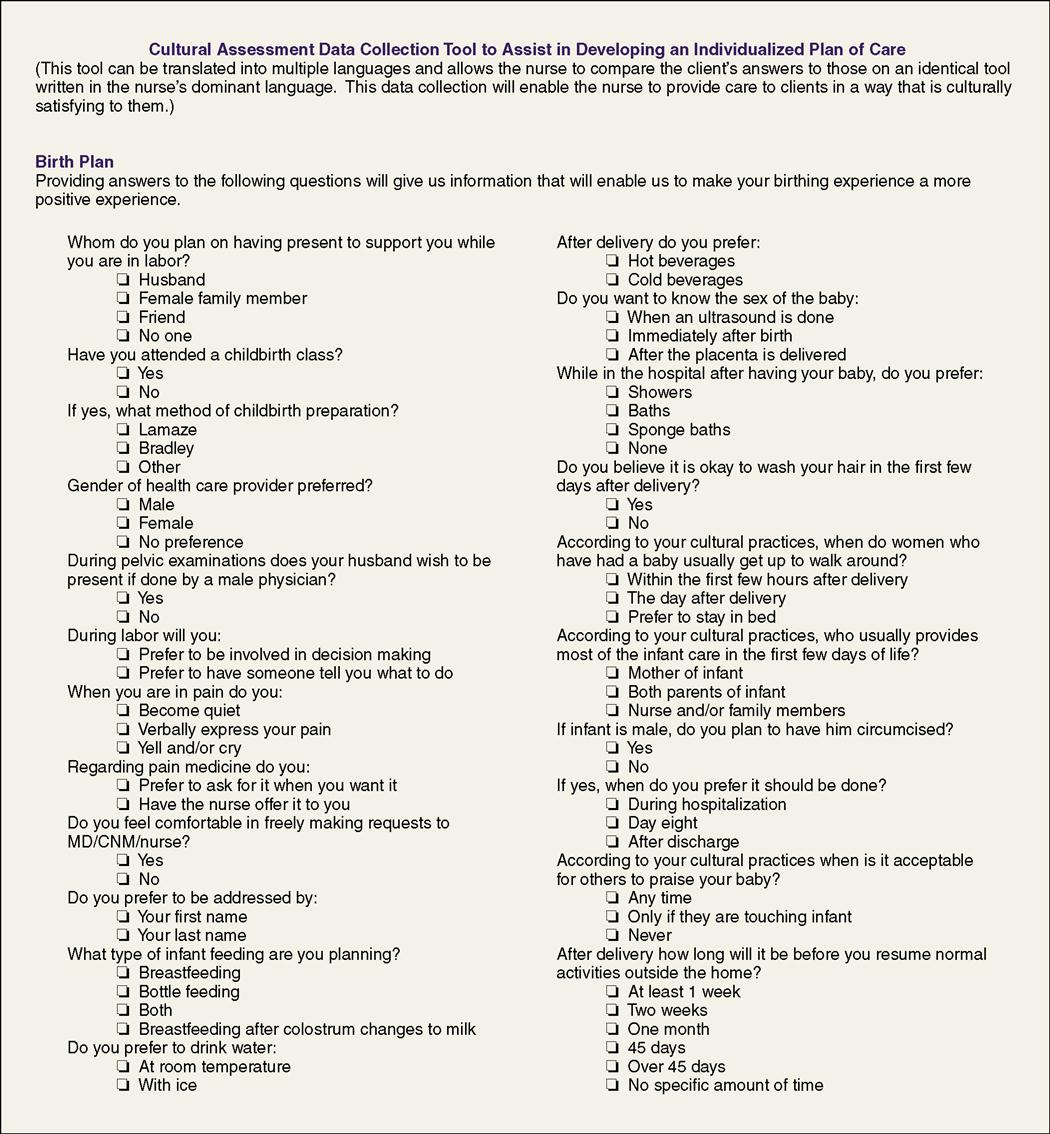

The woman’s lifestyle may include culturally unique beliefs and behaviors that must be considered in a care plan. The focus of education should stand out as a key part of prenatal care and patient-nurse communication. Cultural considerations are important in caring for a woman during her pregnancy. Some cultures view pregnancy and childbirth as normal conditions that do not require any special health care.

Cultural competence is the awareness of, acceptance of, and respect for beliefs, values, traditions, and practices that are different from one’s own. The ability to adapt health care so that it does not violate the culture or religion of the patient is the core of cultural competence. Achieving cultural competence is aided by knowledge, skills, and encounters with others of different cultures. The assumption that all people of one culture believe and behave the same way is cultural stereotyping and should be avoided. Individual differences should be identified and respected (Figure 5-2). For example, in some cultures, such as Orthodox Judaism, the husband may not view the newborn as it is delivered; only verbal encouragement is allowed. Many non-Western cultures expect the woman to have 40 days of rest after delivery. Chinese, African American, Hispanic, and Southeast Asian cultures usually avoid full washing of the body and hair until lochia has ceased. The “hot and cold” theory is observed by many cultures, and, because labor and delivery are considered a “cold” experience, it is balanced by “hot” conditions; therefore, ice water and air-conditioning are avoided. Cambodian women often discard colostrum. In the traditional Japanese culture, newborns are bathed twice a day, and the bathing is accompanied by loud noises to ward off evil spirits.

Prenatal Visits

The initial assessment interview can establish a trusting relationship between the nurse and the pregnant woman. It is a planned, purposeful communication that focuses on specific assessments. Observations include the woman’s subjective interpretations of her health status and the nurse’s objective examination. During the initial communication, the nurse observes the woman’s body language, such as her posture and facial expressions, as well as other physical and emotional signs.

Initial Health and Social History

A health history summary, including a thorough medical and obstetric history, is taken during the first prenatal visit to determine the present status of the woman’s health. First, the nurse obtains personal information, including age, marital status, education, and occupation. Second, the nurse takes the medical history of the woman and her family. The family history and partner’s history are important to identify certain health problems, such as heart disease and genetic disorders that could affect the outcome of pregnancy. The woman’s personal history, including her nutritional history, is important in assessing her present and past health. A cultural history that includes the use of self-medication, complementary or alternative medicine (CAM), alcohol use, or the use of recreational drugs is part of every pregnant woman’s initial health history because it may have an impact on fetal development. Third, the nurse obtains information about the woman’s obstetric history, including any previous pregnancies, birth weight of previous infants, length of previous labors, present attitude toward this pregnancy, date of last normal menstrual period (LNMP), and any problems that arose during a previous pregnancy, labor, birth, and postpartum period. This information can provide clues of what to expect during the present pregnancy.

Social history provides information about the woman’s and partner’s occupations, education, marital status, ethnic or cultural background, and socioeconomic status. Perception of this pregnancy, coping mechanisms, and family support are explored.

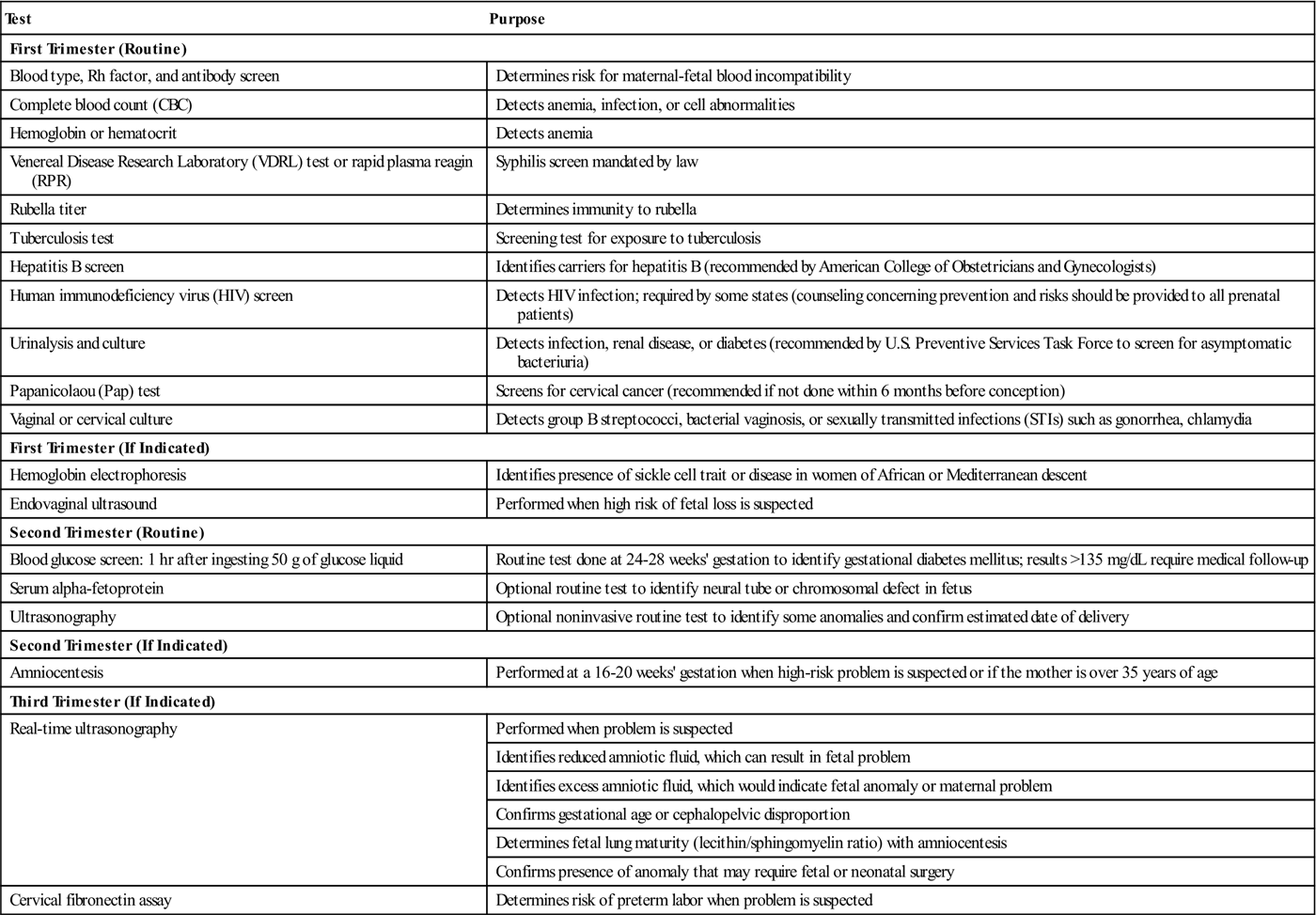

Physical Examination

In the physical examination, the physician or nurse-midwife examines all body systems. This includes a head-to-toe assessment. The patient’s weight and blood pressure are recorded, and microscopic urine examination is performed in the first visit. Baseline weight and blood pressure are important because a sudden change in either is significant. A sudden elevation in blood pressure or sudden excessive weight gain may be a symptom of gestational hypertension (see Chapter 13). The pregnancy examination includes a pelvic examination, which is performed to determine the status of the reproductive organs and the birth canal. Pelvic measurements may be taken to determine whether the pelvis will allow the passage of a fetus at delivery (see Chapter 2). Before the pelvic examination is conducted, the nurse should advise the woman to empty her bladder and to take deep breaths during the examination to lessen her discomfort. Routine laboratory tests are performed throughout the pregnancy (Table 5-1).

Table 5-1

| Test | Purpose |

| First Trimester (Routine) | |

| Blood type, Rh factor, and antibody screen | Determines risk for maternal-fetal blood incompatibility |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Detects anemia, infection, or cell abnormalities |

| Hemoglobin or hematocrit | Detects anemia |

| Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) | Syphilis screen mandated by law |

| Rubella titer | Determines immunity to rubella |

| Tuberculosis test | Screening test for exposure to tuberculosis |

| Hepatitis B screen | Identifies carriers for hepatitis B (recommended by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screen | Detects HIV infection; required by some states (counseling concerning prevention and risks should be provided to all prenatal patients) |

| Urinalysis and culture | Detects infection, renal disease, or diabetes (recommended by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria) |

| Papanicolaou (Pap) test | Screens for cervical cancer (recommended if not done within 6 months before conception) |

| Vaginal or cervical culture | Detects group B streptococci, bacterial vaginosis, or sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia |

| First Trimester (If Indicated) | |

| Hemoglobin electrophoresis | Identifies presence of sickle cell trait or disease in women of African or Mediterranean descent |

| Endovaginal ultrasound | Performed when high risk of fetal loss is suspected |

| Second Trimester (Routine) | |

| Blood glucose screen: 1 hr after ingesting 50 g of glucose liquid | Routine test done at 24-28 weeks’ gestation to identify gestational diabetes mellitus; results >135 mg/dL require medical follow-up |

| Serum alpha-fetoprotein | Optional routine test to identify neural tube or chromosomal defect in fetus |

| Ultrasonography | Optional noninvasive routine test to identify some anomalies and confirm estimated date of delivery |

| Second Trimester (If Indicated) | |

| Amniocentesis | Performed at a 16-20 weeks’ gestation when high-risk problem is suspected or if the mother is over 35 years of age |

| Third Trimester (If Indicated) | |

| Real-time ultrasonography | Performed when problem is suspected |

| Identifies reduced amniotic fluid, which can result in fetal problem | |

| Identifies excess amniotic fluid, which would indicate fetal anomaly or maternal problem | |

| Confirms gestational age or cephalopelvic disproportion | |

| Determines fetal lung maturity (lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio) with amniocentesis | |

| Confirms presence of anomaly that may require fetal or neonatal surgery | |

| Cervical fibronectin assay | Determines risk of preterm labor when problem is suspected |

Modified from Leifer, G. (2011). Introduction to maternity and pediatric nursing (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

Subsequent Visits

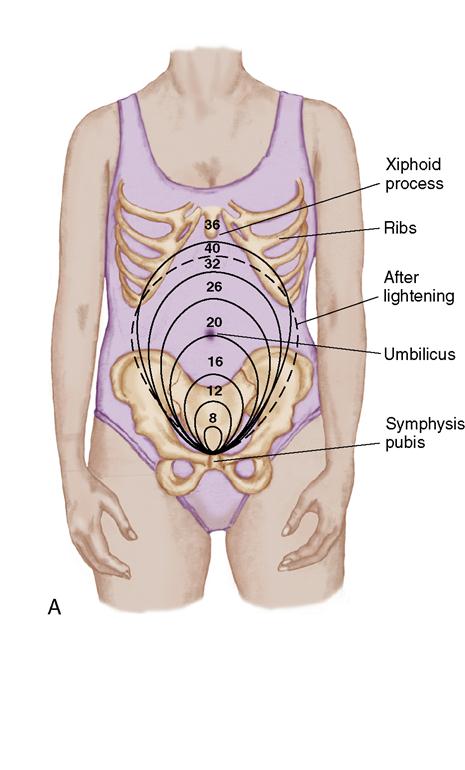

Prenatal visits are scheduled every month for 7 months, every 2 weeks during the eighth month, and every week during the last month if the pregnancy is uneventful (normal). The woman’s weight and blood pressure are recorded, and the urine is checked for protein, acetone, and glucose. These three assessments enable the early detection of hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus. In addition, the physician or midwife measures  the height of the fundus to see whether the pregnancy is progressing at the expected rate (Figure 5-3).

the height of the fundus to see whether the pregnancy is progressing at the expected rate (Figure 5-3).

The woman’s abdomen is palpated with Leopold’s maneuvers to assess the presentation and position of the fetus (see Chapter 7). These consist of four basic maneuvers: (1) determining what is in the fundus, either breech or head (the head is firm and round, whereas the breech feels softer); (2) determining the location of the fetal back (opposite from the extremities); (3) noting what part of the fetus is above the symphysis pubis, either head or breech; and (4) noting the position of the cephalic prominence.

Having determined the presentation and position of the fetus, the nurse then listens to the fetal heart rate. The fetal heart rate can be detected with a Doppler device or with a fetal stethoscope. Tenderness over the woman’s kidney area (costovertebral angle [CVA]) or tenderness in the calf of her leg (Homans’ sign) is assessed because, during pregnancy, a woman is at greater risk for renal infection and thrombophlebitis.

The woman is asked whether she has any discomforts. Sometimes, vague symptoms or subtle clues are the first indication of an impending complication. If the woman has complaints, nursing or medical measures are suggested to relieve them. Early in the subsequent visits, the type of delivery anticipated and how she intends to feed her baby should be discussed. Reassurance of the woman’s capacity to be a good mother is important.

Prenatal Fetal Assessment

High-risk pregnancies are those in which maternal and fetal outcomes are potentially not as good as in a normal pregnancy. The improved understanding of fetal disorders and extraordinary technical advances are changing the management of high-risk pregnancies. Newer diagnostic and therapeutic approaches are being used in the management of complex problems. High-risk pregnancy presents one of the most critical challenges in medical and nursing care. Emphasis must be placed on the safe birth of infants who can develop to their maximum potential (Box 5-2).

This section discusses a range of technologies and procedures designed to reduce risks to the woman and the fetus. These procedures include nursing responsibilities that must be carried out to provide safe care, reduce risks, and meet emotional needs. See Chapter 13 for detailed information concerning complications of pregnancy.

Diagnostic Techniques and Nursing Considerations

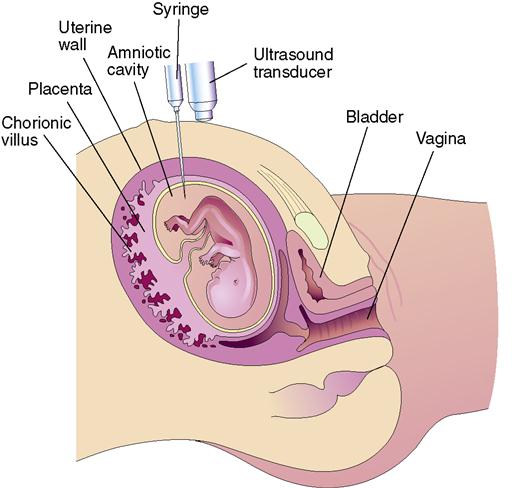

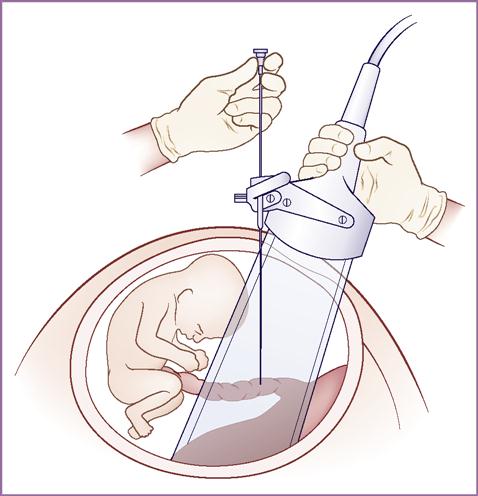

A variety of tests can be used to assess fetal well-being during pregnancy and are indicated when maternal high-risk factors are present (Table 5-2). These tests include diagnostic ultrasound, Doppler ultrasound blood flow, chorionic villi sampling, amniocentesis, percutaneous cord blood sampling, nonstress test (NST), contraction stress test (CST), biophysical profile (BPP), vibroacoustic stimulation test, and maternal assessment of fetal movements (Figures 5-4 to 5-6 on p. 69).

Table 5-2

Tests to Assess Fetal Well-Being

| Test and Description | Major Uses During Pregnancy |

| Ultrasound imaging: High-frequency waves are used to visualize internal organs or tissues within the body (e.g., fetus, placenta, or moving object such as a beating fetal heart); also called ultrasonography; a transvaginal probe or abdominal transducer is used. Abdominal ultrasound requires a full bladder for better visualization (have the woman drink 1-2 qt of water before the examination). Procedure is noninvasive, is painless, and lasts approximately 20 minutes. | Confirms the pregnancy Confirms gestational age Identifies site of implantation (uterine or ectopic) Verifies fetal viability or death Identifies multifetal pregnancy (e.g., twins) Rules out specific fetal abnormalities Evaluates vaginal bleeding and location of placenta Determines amniotic fluid volume Observes fetal movements (fetal heartbeat, breathing, activity, and body movements) Used to guide procedures such as amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling |

| Doppler ultrasound blood flow: Method of noninvasively studying blood flow in maternal and fetal circulations; a hand-held ultrasound device is used. Echo Doppler scan detects fetal heart activity at 6-10 weeks’ gestation. | Assesses maternal-fetal blood flow Detects fetal anemia in Rh isoimmunization May identify intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and placental insufficiency Color Doppler imaging views heart and blood vessel structure and can detect anomalies in vessels within the umbilical cord |

| Chorionic villus sampling: A first-trimester alternative to amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis of some conditions; small amount of the developing placenta (chorionic villi) is aspirated by syringe under the guidance of ultrasound and analyzed. Performed at 10-12 weeks’ gestation. | Recommended only for women at risk for giving birth to baby with a genetic chromosomal or metabolic abnormality (cannot be used to determine spina bifida or anencephaly) Results of chromosome studies available in 24-48 hours Risk of abortion higher than in amniocentesis; potential limb reduction defect in fetus Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) is given to Rh-negative women Can be done earlier in gestation |

| Amniocentesis: Performed to obtain amniotic fluid–containing fetal cells; under direct visualization of ultrasound, a thin needle is inserted through the abdominal and uterine walls to withdraw amniotic fluid into a syringe (with cast-off cells). Sufficient fluid must be present for the test to be done (15-17 weeks’ gestation and 12-14 weeks’ gestation for some disorders). | Early pregnancy Used to assess genetic disorders (e.g., Tay-Sachs disease) Tests for level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), which is also present in maternal blood High AFP levels found in neural tube defects such as spina bifida (open spine) or anencephaly (incomplete development of skull and brain) Low levels of AFP associated with chromosomal disorders or gestational trophoblastic disease Late pregnancy Assesses for severity of maternal-fetal blood incompatibility and fetal lung maturity; RhoGAM given to Rh-negative women Minimal risk for abortion in late pregnancy but higher in early pregnancy Safety concerns: risk of infection, pregnancy loss (although slight), and needle injuries to fetus or placenta |

| Tests for fetal lung maturity: Amniotic fluid obtained by amniocentesis is tested to indicate if fetal lungs are mature enough to adapt to extrauterine life. Lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio: a 2:1 ratio indicates fetal lung maturity (3:1 ratio is desirable for diabetic mother) Presence of phosphatidylglycerol (PG) Foam stability index (FSI, or “shake test”): if ring of bubbles persists for 15 minutes after shaking solution, test is termed positive and indicates surfactant is present and fetal lungs are mature. | Determines whether the fetus is likely to have respiratory distress in adapting to extrauterine life Sometimes used to determine whether the fetal lungs are mature enough before cesarean birth Also evaluates whether the fetus should be removed immediately or whether the lungs should be allowed to develop more in utero after the membranes have ruptured and gestation is <37 weeks (or date is questionable) Absence of PG associated with respiratory distress Blood or meconium in the amniotic fluid alters accuracy of results |

| Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (cordocentesis): Obtaining fetal blood sample from placental vessel or from the umbilical cord by guidance with ultrasound (see Figure 5-6). | Evaluates whether the fetus is anemic and needs a blood transfusion. Identifies Rh isoimmunization in the blood and chromosomal disorders and acid-base status of fetus |

| Nonstress test (NST): Assessment of fetal well-being by evaluating the fetal heart’s ability to accelerate (speed up) in association with fetal movement by using an electronic fetal monitor; accelerations occur either spontaneously or in association with fetal movement. An external electronic monitor is applied while the woman is in a semi-Fowler’s or left-lateral position; conduction gel is put on the abdomen; two belts are applied on the woman’s abdomen; one belt and a device to detect fetal heart rate (FHR) and the other belt detects fetal movement; the woman is given a button to press, which records the time she feels movement on the strip on which the FHR is recorded. The test is continued for up to 40 minutes, or until the criteria for reactivity are met; because almost all accelerations are accompanied by fetal movement, the movement need not be recorded for the test to be reactive. | With adequate accelerations of the FHR, confirms that the placenta is functioning properly and that the fetus is well oxygenated with autonomic functions Blurred response indicative of hypoxia, acidosis, drugs, or fetal sleep Nonreactive NST indicates the fetal heartbeat does not accelerate adequately and further assessment may be required A reactive NST indicates the fetal heartbeat accelerated adequately with fetal movement |

| Contraction stress test (CST): Evaluation of the FHR response to mild uterine contractions by using an electronic fetal monitor. Contractions are induced by intravenous oxytocin (Pitocin) infusion or by self-stimulation of the nipples, which causes the woman’s pituitary gland to release oxytocin; the woman must have at least three contractions of at least 40-seconds duration in a 10-minute period for interpretation of the CST test. | Same purposes as for the NST Negative CST indicates there were no late decelerations of the FHR with three uterine contractions in a 10-minute period Variable accelerations that occur with CST may indicate cord compression |

| Nipple stimulation: Done if inadequate contractions occur. Woman brushes her palm across nipple for 2-3 minutes, stopping when contraction begins; after 5-minute rest period, same process is repeated. To avoid hyperstimulation (uterine contractions lasting 90 seconds or more often than every 2 minutes), bilateral stimulation should not be done unless unilateral stimulation fails. | Stimulate contractions to result in FHR accelerations Intermittent nipple stimulation preferred to prevent hyperstimulation of the uterus |

| Biophysical profile (BPP): Method to evaluate the condition of the fetus that uses five observations: fetal breathing movements, gross fetal movements (movements of body), FHR variability and reactivity (the NST), and the volume of amniotic fluid (amniotic fluid index [AFI]). Some facilities omit the NST, and others assess only the NST or ultrasound and AFI. | Used after 26 weeks’ gestation to assess fetal oxygenation; as fetal hypoxia increases, FHR changes occur first, then decreased breathing movement (<1 breath in 30 minutes), gross body movements (<3 in 20 minutes), and finally loss of muscle tone (failure to open and close the hand) Results immediately available and allow for delay of induction if fetal well-being is confirmed |

| Vibroacoustic stimulation test (vibration and sound): Stimulation of fetus by artificial larynx device; used as an adjunct to the NST. The artificial larynx is applied to the woman’s abdomen over the fetal head, then is activated with a 2- to 3-second stimulus. | Used to clarify whether fetus was sleeping (or inactive) during previous NST Has reduced number of nonreactive NSTs as well as time and cost Fetal accelerations in response to stimulus indicate fetal health |

| Maternal assessment of fetal movement (kick counts): Simple but valuable method for monitoring fetus. It should be encouraged after 28 weeks’ gestation, with women setting aside a consistent time to do the “kick counts.” Mother should count the number of fetal movements for 30-60 minutes 2-3 times a day; other protocols may be used. | Recognizes that the presence of fetal movements is a reassuring sign of fetal health. Decreased fetal movements possibly caused by sleep Cessation of movements correlated with hypoxia and fetal death In the third trimester, woman counts and documents fetal movement for 30-60 minutes twice a day; <4 movements in 30 minutes on 2 consecutive days or <10 movements in 12-hour period should be reported to the health care provider NOTE: Maternal use of drugs may affect fetal activity. |

| Amniotic fluid index (AFI): This ultrasound scan measures the amniotic fluid pockets in all 4 quadrants surrounding the mother’s umbilical area and produces an AFI. A reading of 15-19 cm is considered normal; <5 cm is known as oligohydramnios (decreased amniotic fluid); >30 cm is hydramnios (excess amniotic fluid). | Identifies oligohydramnios, which is associated with growth restriction and fetal distress during labor because of kinking of the umbilical cord Identifies hydramnios, which is associated with fetal anomalies such as gastrointestinal obstruction or fetal hydrops |

| Alpha-fetoprotein test (AFP): Determines the level of this protein in the pregnant woman’s blood serum (MSAFP) or in a sample of amniotic fluid (AFAFP). Correct interpretation requires accurate gestational age. The test is usually performed at 16-18 weeks’ gestation. | High levels associated with open defects such as spina bifida Low levels associated with chromosomal anomalies or hydatidiform mole |

| Triple marker screening: Detects levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and unconjugated estriol. This is often done with AFP test. | May indicate trisomy 18 or 21 if estriol is low and hCG is high. May indicate trisomy 21 if Inhibin A is elevated |

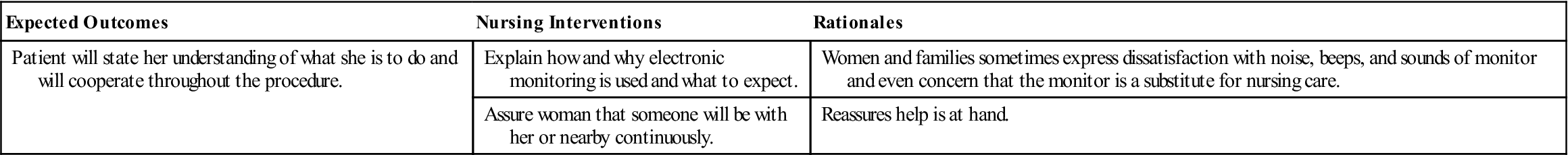

Nursing care during assessments of fetal health, especially with all of the new tests being performed, is important; the woman must understand the reason that specific tests are being performed. The nurse can provide an opportunity for the woman to ask questions regarding the procedure. Clarifying and interpreting test results should be carried out collaboratively by all health care providers involved in the procedures. However, the nurse is often the person who spends the most time with the woman (Nursing Care Plan 5-1 on p. 70).

Psychological Reactions to Diagnostic Testing

Few psychological studies have been performed regarding the impact of antepartum diagnostic testing and monitoring of the fetal heart rate during labor on women’s anxiety levels. However, health care providers have subjectively noticed that the need for testing produces fear. Ultrasound use during pregnancy has become almost routine, and many women expect it to be a part of prenatal care. Some women look forward to the ultrasound because it confirms the pregnancy with visualization of the fetus and the fetal heartbeat. They often learn the sex of the fetus at this time. These factors can have a positive effect on the woman and even promote psychological preparation for attachment to the fetus. Because other prenatal diagnostic testing can provoke anxiety and fear, it is important to allow time for the woman to ask questions and discuss her feelings. The nurse must be particularly sensitive to and respond to the emotional, informational, and comfort needs of the woman and her family. Fetal assessment during labor is discussed in Chapter 7.

Patient Teaching for Self-Care and Common Discomforts of Pregnancy

During the 9 months of pregnancy, women experience various types of discomforts, many of which are a result of normal physiologic changes that take place during pregnancy (discussed in Chapter 4). Nurses and other health care professionals often refer to these discomforts as minor, but the pregnant woman does not consider them minor. If discomforts are not anticipated or expected, they can make her feel anxious and worried. These discomforts can usually be relieved or prevented by simple measures (Table 5-3 on pp. 71–72). Teaching women about self-care is important (Figure 5-7 on p. 72).

Table 5-3

Self-Care for Common Discomforts of Pregnancy

| Discomfort | Influencing Factors | Self-Care Measures |

| First Trimester | ||

| Nausea with or without vomiting | Elevation in hormones, decrease in gastric motility, fatigue, emotional factors; usually does not last beyond 16 weeks if vomiting persists, may lead to hyperemesis gravidarum | Avoid an empty stomach. Eat dry crackers or toast ½ to 1 hour before rising in the morning. Eat small, frequent meals. Drink fluids between meals. Avoid greasy, odorous, spicy, or gas-forming foods. Increase vitamin B6. |

| Breast tenderness | Increased vascular supply and hypertrophy of breast tissue caused by estrogen and progesterone Results in tingling, fullness, and tenderness | Wear a supportive bra (to alleviate tingling and tenderness). Avoid soap to the nipples (to prevent cracking). |

| Urinary frequency | Pressure of growing uterus on bladder in both first and third trimesters Progesterone relaxes smooth muscles of bladder | Void when urge is felt (to prevent urinary stasis); increase fluid intake during day. Decrease fluid in late evening to lessen nocturia; limit caffeine. Practice Kegel exercises. |

| Vaginal discharge (leukorrhea) | Increased production of mucus by endocervical glands in response to elevated estrogen levels and increased blood supply to the pelvic area, causing white, viscid vaginal discharge | Bathe or shower daily. Wear cotton underwear. Avoid tight undergarments and pantyhose. Keep the perineal area clean and dry. Avoid douching and using tampons. Wipe the perineal area from front to back after toileting. Contact health care provider if there is a change in color, odor, or character of discharge. |

| Second and Third Trimesters | ||

| Heartburn (pyrosis) | Increased production of progesterone causing relaxation of esophageal sphincter Regurgitation or backflow of gastric contents into the esophagus causing burning sensation behind the sternum, burping, and sour tastes in mouth | Sit up for 30 minutes after eating a meal. Avoid gas-forming and greasy foods. Avoid overeating. Use low-sodium liquid antacids such as Gelusil or Maalox (liquid will coat lining better than tablets); avoid sodium bicarbonate and Alka Seltzer. |

| Constipation and flatulence (gas) | Increased levels of progesterone causing bowel sluggishness, with increased water absorption (results in hardened stool) Pressure of enlarging uterus on intestine Diet, lack of exercise, and decreased fluids | Increase fluid intake (a minimum of 8 glasses per day, not including carbonated or caffeinated beverages because of their diuretic effect), roughage in diet, and exercise. Exercise to stimulate peristalsis. |

| Iron supplements contributing to hardening of stools | Establish regular schedule for bowel movement. Do not take mineral oil or enemas. Consult health care provider about taking a stool softener (docusate). | |

| Hemorrhoids | Varicosities (distended veins) of rectum caused by vascular enlargement of pelvis, straining from constipation, and descent of fetal head into pelvis May disappear after birth, when pressure is relieved | Use anesthetic ointment, cool witch hazel pads, or rectal suppositories. May disappear after birth, when pressure is relieved Take sitz baths, increase fiber in diet, and have regular bowel habits to avoid constipation. |

| Backaches | Result of the spine’s adaptation to posture changes as the uterus enlarges Enlarging uterus altering center of gravity, resulting in lordosis (exaggeration of lumbosacral curve) and muscle strain | Maintain correct posture with head up and shoulders back; use good body mechanics. Avoid exaggerating lumbar curve. Squat rather than bending over when picking up objects (bend at knees, not waist). Wear low-heeled shoes to help maintain better posture. Do exercises such as tailor sitting (cross-legged), shoulder circling, and pelvic rocking. Rest; applying localized heat may help. |

| Round ligament pain | Abdominal ligaments stretched by enlarging uterus, causing pain in lower abdomen after sudden movements | Avoid jerky or quick movements. Use pillow support for abdomen. Use good body mechanics. |

| Leg cramps | Pressure of uterus on blood vessels that impairs circulation to legs, causing muscle strain and fatigue Imbalance in the calcium/phosphorus ratio | Dorsiflex foot and straighten leg with downward pressure on knee or stand with feet flat on floor when cramps occur (see Figure 5-7). Evaluate diet and calcium intake. |

| Headache | Emotional tension and fatigue Increased circulatory blood volume and heart rate causing dilation and distention of cerebral vessels | Obtain emotional support. Practice relaxation exercises. Eat regular meals. If headaches continue, report to caregiver (potential gestational hypertension). |

| Varicose veins | Relaxation of smooth muscle in walls of veins caused by elevated progesterone Pressure of enlarging uterus causing pressure on veins, resulting in development of varicosities in vulva, rectum, and legs | Avoid lengthy standing or sitting, constrictive clothing, and bearing down during bowel movements. Walk frequently. Rest with legs elevated. Wear support stockings; avoid tight knee-highs. Exercise (to stimulate venous return). Relieve hemorrhoid swelling with warm sitz baths, local application of astringent compresses, or analgesic ointment. |

| Edema of feet and ankles | Circulatory congestion of lower extremities | Elevate legs when sitting. Increase rest periods. Avoid constrictive clothing and prolonged standing or sitting. |

| Faintness and dizziness | Vasomotor instability or postural hypotension Standing for long periods with venous stasis in lower extremities | Avoid sudden changes in position, prolonged standing, and warm crowded areas. Move slowly from rest position. Avoid hypoglycemia by eating 4-5 small meals daily. Lie on left side when resting to avoid supine hypotensive syndrome (pressure of uterus on vena cava). If symptoms do not lessen, report to caregiver. |

| Fatigue | Hormonal changes in early pregnancy and periodic hypoglycemia as glucose is used by embryo for rapid growth More prominent in early months of pregnancy | Try to get 8-10 hours of sleep. Take naps during the day if possible. Use relaxation techniques, meditation, or change of scenery. |

| Dyspnea | Later in pregnancy, caused by uterus rising into abdomen and pressing on diaphragm | Sleep with several pillows under head. Use deep chest breathing before going to sleep. Use proper posture while sitting or standing. Avoid exertion. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Care Plan 5-1

Nursing Care Plan 5-1