Substance Abuse

Objectives

1 Differentiate among the key terms associated with substance abuse.

3 Cite the responsibilities of professionals who suspect substance abuse by a colleague.

4 Explain the primary long-term goals in the treatment of substance abuse.

5 Identify the withdrawal symptoms for major substances that are commonly abused.

Key Terms

substance abuse ( ) (p. 828)

) (p. 828)

impairment ( ) (p. 828)

) (p. 828)

dependence ( ) (p. 828)

) (p. 828)

addiction ( ) (p. 828)

) (p. 828)

illicit substance ( ) (p. 828)

) (p. 828)

intoxication ( ) (p. 836)

) (p. 836)

Definitions of Substance Abuse

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) defines substance-related disorders as those that arise from (1) the taking of a drug of abuse, (2) the adverse effects of a medication, and (3) toxin exposure. The DSM-IV-TR groups substances of abuse into 11 categories (Box 49-1). Many other medications taken for therapeutic purposes can induce substance-related disorders as an adverse effect, especially when large doses of the medications are taken (Box 49-2). Symptoms usually disappear when the dosage is lowered or the medication is stopped. Volatile substances are classified as inhalants if they are used for the purpose of becoming intoxicated, but are defined as toxins if exposure is accidental or part of intentional poisoning. Impairments in cognition or mood are the most common symptoms associated with toxic substances, although anxiety, hallucinations, delusions, or seizures also can occur. The symptoms usually disappear when exposure stops, but resolution of symptoms may take up to several months of treatment (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Substances of Abuse

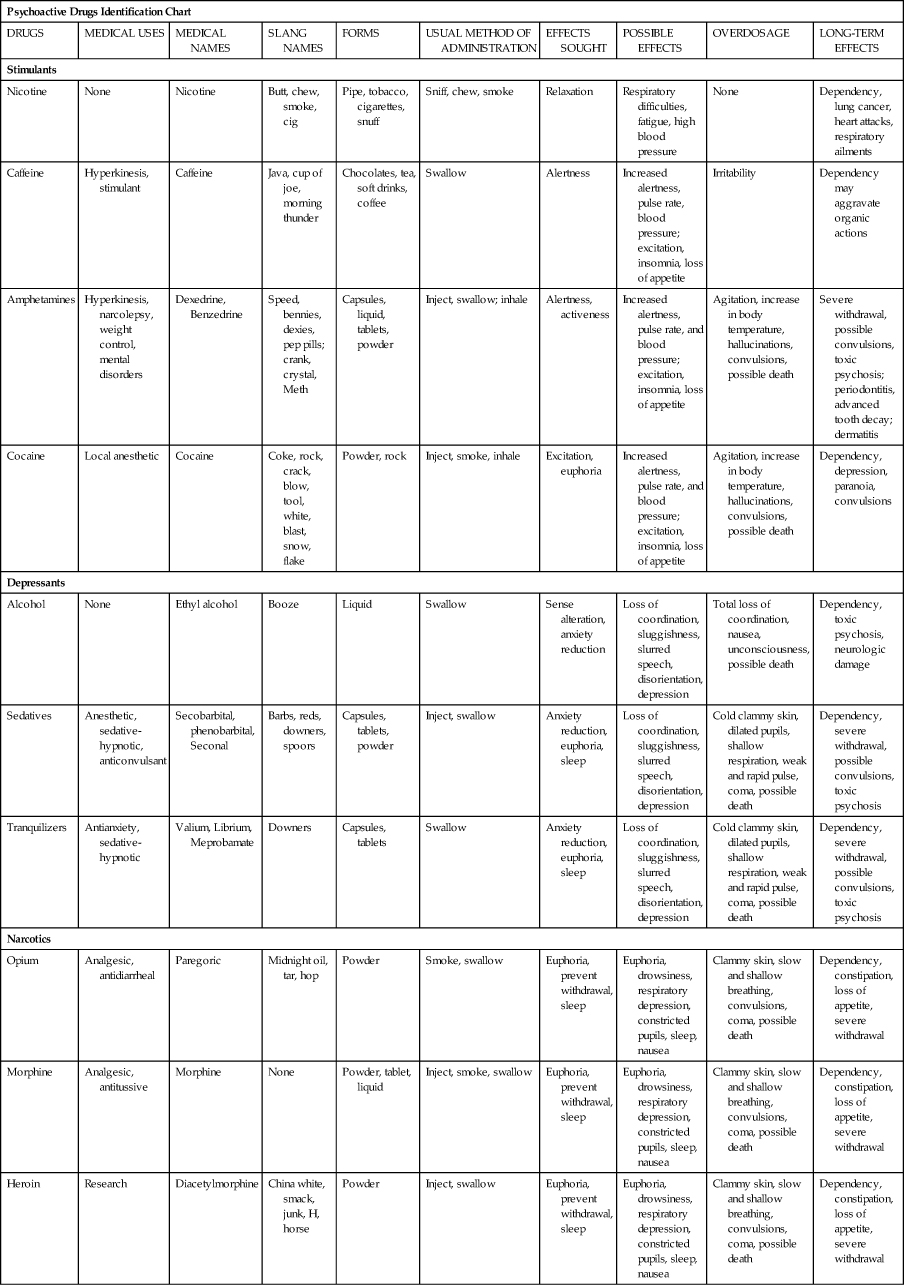

Substance abuse is defined as the periodic purposeful use of a substance that leads to clinically significant impairment. The impairment results in failure to fulfill major obligations at work, school, or home (e.g., absenteeism, poor work performance, neglect of responsibilities); places the person in physically hazardous situations (e.g., operating a vehicle or machinery when impaired); and creates legal problems (e.g., arrests for intoxication, disorderly conduct) or social problems that are aggravated by the substance (e.g., physical fights, spousal arguments). If substance abuse behavior is not stopped, substance abuse may lead to another more serious medical condition known as substance dependence (commonly known as addiction). Symptoms of addiction include overwhelming compulsive use, tolerance, and withdrawal on discontinuation. A phrase that characterizes chemical dependency is “using a substance to live and living to use.” The amount of drug exposure and the frequency of use necessary to develop dependence are unknown and highly individual, based on the pharmacology of the drug, emotional condition, heredity, and environmental factors. A term frequently associated with substance abuse is illicit substance—any chemical or mixture of chemicals that alters biologic function and is not required to maintain health. The term illicit substances applies primarily to illegal substances. Any chemical that can produce a pleasurable state of mind has potential for abuse. Commonly abused substances, their pharmacologic effects, their street names, and their potential long-term consequences are listed in Table 49-1.

Table 49-1

| Psychoactive Drugs Identification Chart | |||||||||

| DRUGS | MEDICAL USES | MEDICAL NAMES | SLANG NAMES | FORMS | USUAL METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION | EFFECTS SOUGHT | POSSIBLE EFFECTS | OVERDOSAGE | LONG-TERM EFFECTS |

| Stimulants | |||||||||

| Nicotine | None | Nicotine | Butt, chew, smoke, cig | Pipe, tobacco, cigarettes, snuff | Sniff, chew, smoke | Relaxation | Respiratory difficulties, fatigue, high blood pressure | None | Dependency, lung cancer, heart attacks, respiratory ailments |

| Caffeine | Hyperkinesis, stimulant | Caffeine | Java, cup of joe, morning thunder | Chocolates, tea, soft drinks, coffee | Swallow | Alertness | Increased alertness, pulse rate, blood pressure; excitation, insomnia, loss of appetite | Irritability | Dependency may aggravate organic actions |

| Amphetamines | Hyperkinesis, narcolepsy, weight control, mental disorders | Dexedrine, Benzedrine | Speed, bennies, dexies, pep pills; crank, crystal, Meth | Capsules, liquid, tablets, powder | Inject, swallow; inhale | Alertness, activeness | Increased alertness, pulse rate, and blood pressure; excitation, insomnia, loss of appetite | Agitation, increase in body temperature, hallucinations, convulsions, possible death | Severe withdrawal, possible convulsions, toxic psychosis; periodontitis, advanced tooth decay; dermatitis |

| Cocaine | Local anesthetic | Cocaine | Coke, rock, crack, blow, tool, white, blast, snow, flake | Powder, rock | Inject, smoke, inhale | Excitation, euphoria | Increased alertness, pulse rate, and blood pressure; excitation, insomnia, loss of appetite | Agitation, increase in body temperature, hallucinations, convulsions, possible death | Dependency, depression, paranoia, convulsions |

| Depressants | |||||||||

| Alcohol | None | Ethyl alcohol | Booze | Liquid | Swallow | Sense alteration, anxiety reduction | Loss of coordination, sluggishness, slurred speech, disorientation, depression | Total loss of coordination, nausea, unconsciousness, possible death | Dependency, toxic psychosis, neurologic damage |

| Sedatives | Anesthetic, sedative-hypnotic, anticonvulsant | Secobarbital, phenobarbital, Seconal | Barbs, reds, downers, spoors | Capsules, tablets, powder | Inject, swallow | Anxiety reduction, euphoria, sleep | Loss of coordination, sluggishness, slurred speech, disorientation, depression | Cold clammy skin, dilated pupils, shallow respiration, weak and rapid pulse, coma, possible death | Dependency, severe withdrawal, possible convulsions, toxic psychosis |

| Tranquilizers | Antianxiety, sedative-hypnotic | Valium, Librium, Meprobamate | Downers | Capsules, tablets | Swallow | Anxiety reduction, euphoria, sleep | Loss of coordination, sluggishness, slurred speech, disorientation, depression | Cold clammy skin, dilated pupils, shallow respiration, weak and rapid pulse, coma, possible death | Dependency, severe withdrawal, possible convulsions, toxic psychosis |

| Narcotics | |||||||||

| Opium | Analgesic, antidiarrheal | Paregoric | Midnight oil, tar, hop | Powder | Smoke, swallow | Euphoria, prevent withdrawal, sleep | Euphoria, drowsiness, respiratory depression, constricted pupils, sleep, nausea | Clammy skin, slow and shallow breathing, convulsions, coma, possible death | Dependency, constipation, loss of appetite, severe withdrawal |

| Morphine | Analgesic, antitussive | Morphine | None | Powder, tablet, liquid | Inject, smoke, swallow | Euphoria, prevent withdrawal, sleep | Euphoria, drowsiness, respiratory depression, constricted pupils, sleep, nausea | Clammy skin, slow and shallow breathing, convulsions, coma, possible death | Dependency, constipation, loss of appetite, severe withdrawal |

| Heroin | Research | Diacetylmorphine | China white, smack, junk, H, horse | Powder | Inject, swallow | Euphoria, prevent withdrawal, sleep | Euphoria, drowsiness, respiratory depression, constricted pupils, sleep, nausea | Clammy skin, slow and shallow breathing, convulsions, coma, possible death | Dependency, constipation, loss of appetite, severe withdrawal |

| Codeine | Analgesic, antitussive | Codeine, Empirin compound with codeine, Robitussin AC | None | Capsules, tablets, liquid | Inject, swallow | Euphoria, prevent withdrawal, sleep | Euphoria, drowsiness, respiratory depression, constricted pupils, sleep, nausea | Clammy skin, slow and shallow breathing, convulsions, coma, possible death | Dependency, constipation, loss of appetite, severe withdrawal |

| Cannabis | |||||||||

| THC | Research, cancer chemotherapy antinauseant | Tetrahydro-cannabinol | THC | Tablets, liquid | Swallow | Relaxation, euphoria, increased perception | Relaxed inhibitions, euphoria, increased appetite, distorted perceptions, disoriented behavior | Fatigue, paranoia, possible psychosis | Amotivational syndrome, respiratory difficulties, lung cancer, interference with physical and emotional development |

| Hashish | None | Tetrahydro-cannabinol | Hash | Solid resin | Smoke | Relaxation, euphoria, increased perception | Relaxed inhibitions, euphoria, increased appetite, distorted perceptions, disoriented behavior | Fatigue, paranoia, possible psychosis | Amotivational syndrome, respiratory difficulties, lung cancer, interference with physical and emotional development |

| Marijuana | Research | Tetrahydro-cannabinol | Pot, grass, doobie, ganja, dope, gold, herb, weed, reefer | Plant particles | Smoke, swallow | Relaxation, euphoria, increased perception | Relaxed inhibitions, euphoria, increased appetite, distorted perceptions, disoriented behavior | Fatigue, paranoia, possible psychosis | Amotivational syndrome, respiratory difficulties, lung cancer, interference with physical and emotional development |

| Hallucinogens | |||||||||

| PCP | None | Phencyclidine | Angel dust, zoot, peace pill, hog | Tablets, powder | Smoke, swallow | Distortion of sense, insight, exhilaration | Illusions and hallucinations, distorted perception of time and distance | Longer and more intense “trips” or episodes, psychosis, convulsions, possible death | May intensify existing psychosis, flashbacks, panic reactions |

| LSD | Research | Lysergic acid diethylamide | Acid, sugar | Capsules, tablets, liquid | Swallow | Distortion of sense, insight, exhilaration | Illusions and hallucinations, distorted perception of time and distance | Longer and more intense “trips” or episodes, psychosis, convulsions, possible death | May intensify existing psychosis, flashbacks, panic reactions |

| Organics | None | Mescaline, psilocybin | Mesc, mushroom | Crude preparations, tablets, powder | Swallow | Distortion of sense, insight, exhilaration | Illusions and hallucinations, distorted perception of time and distance | Longer and more intense “trips” or episodes, psychosis, convulsions, possible death | May intensify existing psychosis, flashbacks, panic reactions |

| Inhalants | |||||||||

| Aerosols and solvents | None | None | Glue, benzene, toluene, Freon | Solvents, aerosols | Inhale | Intoxication | Exhilaration, confusion, poor concentration | Heart failure, unconsciousness, asphyxiation, possible death | Impaired perception, coordination, and judgment; neurologic damage |

From the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention: Curriculum modules on alcohol and other drug problems for schools of social work, Rockville, MD, 1995, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention.

Substance abuse is a societal issue that plagues many cultures and all races throughout the world. In the United States, as many as one in four individuals meet the criteria for a substance use disorder at some time in their lives. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (formerly the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse), an estimated 22.1 million Americans (8.7% of the U.S. population) age 12 and older were classified in 2010 with dependence on, or abuse of, alcohol or illicit drugs. Of these, 2.9 million were classified with dependence on or abuse of both alcohol and illicit drugs, 4.2 million were dependent on or abused illicit drugs but not alcohol, and 15 million were dependent on or abused alcohol but not illicit drugs. The number of people with substance dependence or abuse increased from 14.5 million (6.5% of the U.S. population) in 2000 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

Theories on Why Substances are Abused

Even though substance abuse has been a condition of the human mind since prehistoric times and very extensively studied, there is no one theory that accounts for why individuals abuse chemicals. The major theories of substance abuse are classified as biologic, psychological, and sociocultural models (Taylor and Stuart, 2009). Belief in any particular theory influences assessment and treatment.

The biologic model hypothesizes that substance abuse is caused by a person’s genetic profile, making a predisposition to substance abuse a hereditary condition. Specific genes have been found that appear to be associated with alcoholism and possibly other types of substance abuse. It is thought that these genetic aberrations block feelings of well-being, resulting in anxiety, anger, low self-esteem, and other negative feelings, leaving a feeling of craving for a substance that will suppress the bad feelings. Genes may also play a role in the alteration of metabolic enzyme systems in the body that enhance or detract from pleasurable responses to chemical substances.

Many psychological theories have been studied that attempt to explain why people abuse chemicals. Psychoanalytic theories see alcoholics as fixated at the oral stage of development, thus seeking need satisfaction through oral behaviors such as drinking. Behavior or learning theories view addictive behaviors as overlearned maladaptive habits that can be examined and changed in the same way as other habits. Cognitive theories suggest that addiction is based on a distorted way of thinking about substance use. Family system theory emphasizes the pattern of relationships among family members through the generations as an explanation of substance abuse.

Substance abuse has been linked to several psychological traits (e.g., depression, anxiety, antisocial personality, dependent personality), but there is no particular evidence that these traits cause the substance abuse. It is quite possible that long-term substance abuse causes these traits. There also does not appear to be a specific type of addictive personality because there is a wide variety of personality types among those who become alcoholics. Unfortunately, after long-term substance abuse, personality patterns emerge from the effects of alcohol and/or drugs on previously normal psychological functions, combined with ineffective responses to these effects.

Sociocultural factors play a role in a person’s choice of whether or not to seek treatment, to use drugs, which drugs to use, and how much to use for treatment of substance abuse. Attitudes, values, norms, and sanctions differ according to nationality, religion, gender, family background, and social environment. Combinations of factors may make a person more susceptible to drug abuse and interfere with recovery. Assessment of these factors is necessary to understand the whole person.

Signs of Impairment

When signs of impairment start showing, it is usually not one sign alone but a cluster that raise questions of an impairment problem. The disease is usually first manifested in family life (e.g., domestic violence, separation, financial problems, problem behavior in children) and then in social life (e.g., overt public intoxication; isolation from friends, peers, church). Physical and mental changes may be manifested by excessive tiredness, multiple illnesses, frequent injuries or accidents, and emotional crises. Deterioration in physical status is an important sign, but occurs late in the disease. Flagrant evidence of impairment at the worksite is relatively rare and usually occurs after the disease is advanced. In many cases, the workplace is the source of the drug of choice, so the impaired person will strive to protect the source with appropriate behavior.

Screening for Alcohol and Substance Abuse

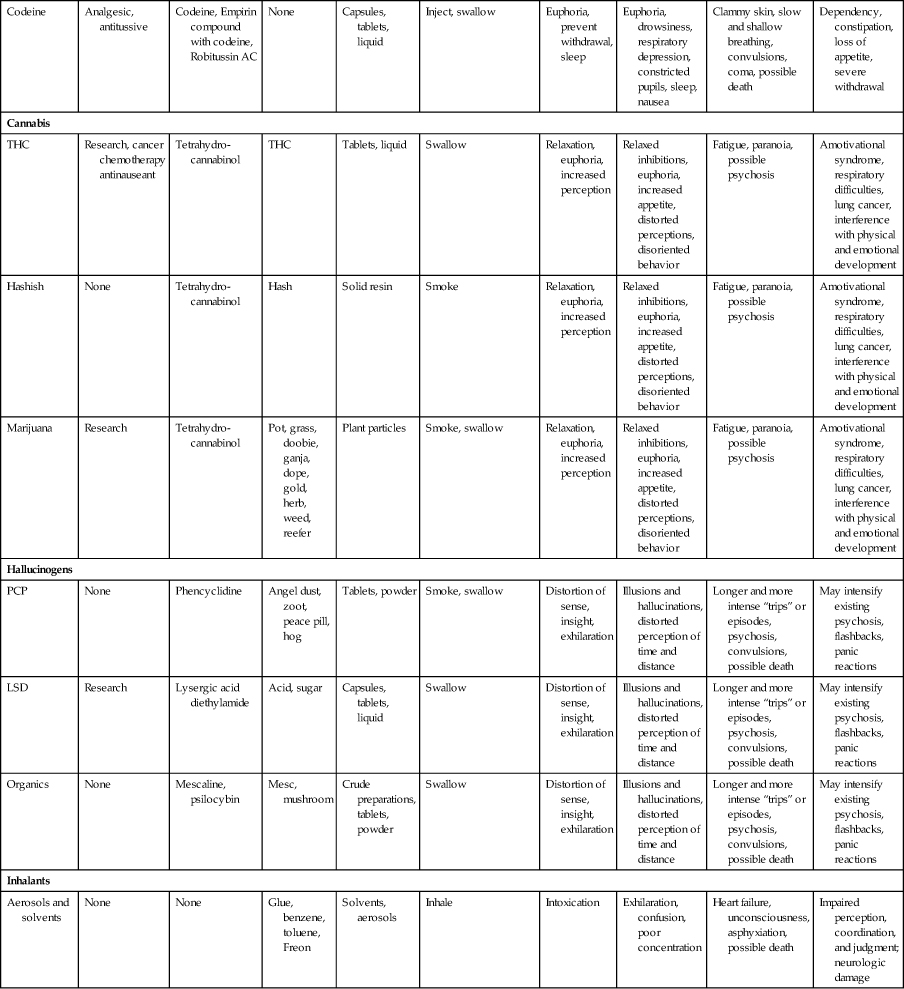

Because of the large number of health problems associated with alcohol and substance abuse, Healthy People 2020, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Medical Association, and the American Nurses Association support and encourage screening patients for alcohol and other substance abuse. Screening instruments for substance abuse can be divided into the following four categories: (1) comprehensive drug abuse screening and assessment; (2) brief drug abuse screening; (3) alcohol abuse screening; and (4) drug and alcohol abuse screening for use with adolescents (Table 49-2). All the screening instruments listed have been validated for accuracy for specific purposes (e.g., differentiating between early detection of excessive drinking versus alcoholism, the potential for substance abuse versus substance addiction). Another example of assessment for specific purposes is the Drug Abuse Screening Test, which can be used to differentiate among alcohol problems only, drug problems only, and both drug and alcohol problems. Some instruments are designed to be administered through an interview by a trained health professional, whereas others are designed for self-assessment by the patient using pencil and paper or computer entry. It is crucial that the proper assessment instrument be selected for use with a specific patient to attain meaningful results for an appropriate diagnosis. A disadvantage of some of the comprehensive screening instruments is the length of time required to administer the assessment and the availability of a qualified data interpreter. Many of the comprehensive instruments have been modified to be used as quick-screening instruments. A four-question assessment for alcohol abuse commonly used in the primary care setting because of its ease of administration is the CAGE questionnaire. CAGE (cut down, annoyed, guilty, and eye opener) is an acronym that provides the interviewer with a quick reminder of questions to be asked about the patient’s feelings toward his or her intake of substances (Ewing, 1984). A disadvantage of many of the instruments is that they were developed using adult male patients and have not been validated in special populations (e.g., women, older adults, and adolescents).

Table 49-2

Screening Instruments for Substance Abuse

| NAME OF INSTRUMENT | ACRONYM |

| Comprehensive Drug Abuse Screening and Assessment Instruments | |

| Addiction Severity Index | ASI |

| Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test | ASSIST |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test | AUDIT |

| Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module | CIDI-SAM |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test | DAST |

| Drug Use Screening Inventory | DUSI |

| Individual Assessment Profile | IAP |

| MacAndrew Scale | MAC |

| Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory | MCMI |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory | MMPI |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 | MMPI-2 |

| Brief Drug Abuse Screening Instruments | |

| CAGE–Adapted to Include Drugs | CAGE-AID |

| Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory | MCMI |

| Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory Drug Dependence Scale | MCMI-III |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 | MMPI-2 |

| Addiction Potential Scale | API |

| Addiction Acknowledgment Scale | AAS |

| Screening Instrument of Substance Abuse Potential | SISAP |

| Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test—Adapted to Include Drugs | SMAST-AID |

| Alcohol Abuse Screening Instruments | |

| CAGE | CAGE |

| Michigan Alcohol Screening Test | MAST |

| Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory | MCMI |

| Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory Alcohol Dependence Scale | MCMI-III |

| Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test | SMAST |

| Drug and Alcohol Screening Instruments For Adolescents | |

| Adolescent Alcohol Involvement Scale | AAIS |

| Adolescent Drug Abuse Diagnosis | ADAD |

| Adolescent Drinking Inventory | ADI |

| Adolescent Drug Involvement Scale | ADIS |

| Comprehensive Adolescent Severity Inventory | CASI |

| Drug and Alcohol Quick Screen | DAP |

| Home, Education/Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/Depression | HEADSS |

| Home, Education, Abuse, Drugs, Safety, Friends, Image, Recreation, Sexuality, and Threats | HEADS FIRST |

| Problem-Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers | POSIT |

Modified from McPherson TL, Hersch PK: Brief substance use screening instruments for primary care settings: A review, J Subst Abuse Treat 18:193-202, 2000.

Health Professionals and Substance Abuse

Although the prevalence of substance abuse among physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals is not precisely known, it is probably similar to that of the general population. There is thought to be more prescription drug use and less street drug use because of easier access to prescription drugs. It is a misperception that education somehow protects health misconception from addiction because “they know better.” An individual’s inability to manage stress brought on by intense patient care practice, managing more patients with the same resources, zero tolerance for making a mistake in association with the expectation of 100% perfection, and financial debt are thought to be major contributing factors to substance abuse among health professionals.

Health professionals are responsible for maintaining a code of ethics and standards of care, and the inappropriate use of substances puts these principles in jeopardy. Signs that raise suspicion of substance abuse include behavioral changes (e.g., wearing long-sleeved garments all the time, diminished alertness, lack of attention to hygiene, mood swings) and performance deterioration (e.g., requests for frequent schedule changes, errors in clinical judgment, excessive absenteeism, frank odor of alcohol on the breath and attempts to camouflage it with breath fresheners, frequent or long breaks, or deterioration in professional practice and patient care).

If a health professional suspects that a colleague is impaired, a confidential report should be made to an appropriate supervisor familiar with institutional policy. An investigation should be initiated; observation and documentation are crucial to building a record of repeat instances over time to support the suspicion of impairment. Because of faulty memory on the part of the impaired individual, examples of inappropriate actions need to be well documented over time. An accurate record can also be useful in helping the impaired individual recognize the problem and submit voluntarily to treatment.

When considering whether to report a colleague for suspected drug abuse, remember the following:

Legal Considerations of Substance Abuse and Dependence

All states have laws pertaining to the reporting of impairment of health care workers. Some require that suspected impairment be reported to the health professional’s licensure or disciplinary board. Other states allow referral to a professional society’s impairment committee, which then contracts with the impaired individual to participate in a recovery program. As long as the health professional continues to participate, the committee can refrain from notifying the licensure board.

The health professional who makes a conscious effort to be treated for an addictive disorder has a variety of legal protections that can be helpful to reestablishing a career. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which went into effect in 1992, defines a disabled person as one “with a physical or mental impairment seriously limiting one or more major life activities.” People dependent on drugs, but who are no longer using drugs illegally and are receiving treatment for chemical dependence or who have been rehabilitated successfully, are protected by the ADA from discrimination on the basis of past drug addiction. However, a substance abuser whose current use of chemicals impairs job performance or conduct may be disciplined, discharged, or denied employment to the extent that this person is not a “qualified individual with a disability.” An individual who is currently engaging in the illegal use of drugs is not an “individual with a disability” under the ADA. State and federal handicap laws also mandate that every employer, including health care institutions, ensure that each recovering chemically impaired individual who applies for employment or reinstatement be afforded the same protection received by anyone with a handicap.

Once a chemically dependent person has been through treatment, an ongoing monitoring program is routinely established to help ensure that the person is free of the abused substance. Urinalysis for drugs is the most common form of drug testing. The Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 encourages (but does not require) drug screening in an effort to provide drug-free workplaces. The Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act Amendments of 1989 extend this act to all educational institutions.

The Supreme Court has ruled that drug screening does not violate one’s constitutional right to privacy or represent unreasonable search. Drug screening may be required for employment and can be requested for cause (e.g., suspicious behavior; arrest; after an accident), or a random test can be requested as a part of a return-to-work agreement for people in recovery. A positive drug test means that the reported drug is present in the specimen. It does not establish that the person is dependent on the drug, and it does not, by itself, prove the drug was the cause of an impaired performance.

Educating Health Professionals About Substance Abuse

The curricula of health profession educational programs should ensure that all students have multiple opportunities during their development of professional attitudes and behaviors to consider and formulate values about self-medication and substance abuse consistent with professional and legal standards. Employers should make available drug abuse resources, such as information about employee assistance programs and policies, professional recovery assistance (e.g., recovery networks), and educational opportunities. Prevention of drug misuse, whether it is illegal or inappropriate use or drug abuse, is an important priority in the practice of every health profession.

Principles of Treatment for Substance Abuse

It is important to recognize that substance abuse and addiction are diseases as described in DSM-IV-TR and are treatable disorders. This focus is essential to successful treatment. The American Psychiatric Association lists long-term goals in treating substance abuse as follows:

• Reduction or abstinence in the use and effects of substances

• Reduction in the frequency and severity of relapse

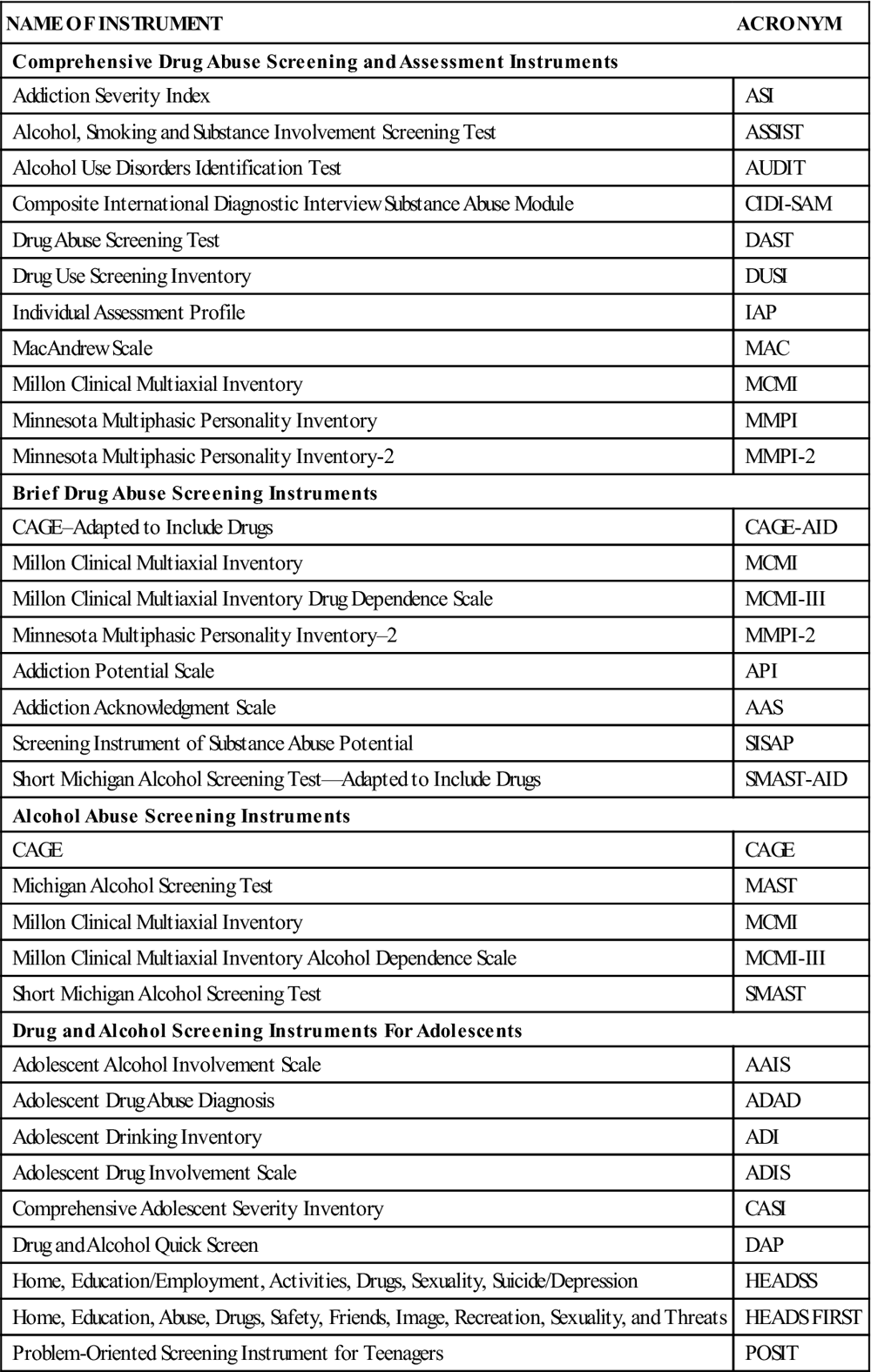

By the time a person seeks treatment for substance abuse or is ordered into a treatment program by the courts, the illness has become very complex, affecting almost every aspect of the person’s life. Treatment requires lifelong effort, with a combination of psychosocial support and sometimes pharmacologic treatment. Key factors associated with long-term recovery are negative consequences of substance use (e.g., deteriorating health, divorce, loss of job, problems with family and friends) and social and community support, particularly with participation by self-help organizations whose goals include total abstinence of substances being abused (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Women for Sobriety, Rational Recovery). The types of social support given by the 12-step programs (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous), such as 24-hour availability when cravings arise, networking, role modeling and advice on abstinence based on direct, personal experiences, appear to be primary characteristics for success in maintaining recovery (Figure 49-1).

Diagnostic criteria for assessment of substance abuse and related disorders are defined in the DSM-IV-TR. A combination of interviews, screening tools (see Table 49-2), information from colleagues, and laboratory tests will determine whether there is a single diagnosis of abuse of one or more substances or if there are multiple diagnoses. Other psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, psychosis, delirium, dementia) and medical conditions (e.g., anemia, cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, nutrition deficiencies, cardiomyopathy) may be induced by substance abuse. Based on the findings, priorities must be assigned. Immediate medical needs must be addressed first (e.g., thiamine deficiency, withdrawal and detoxification, safety). Detoxification programs are an important first step in substance abuse treatment. Detoxification initiates abstinence, reduces the severity of withdrawal symptoms, and retains the person in treatment to forestall relapse. During detoxification, behavioral interventions (e.g., contingency management, motivational enhancement, and cognitive therapies) can also be started.

Alcohol

In the United States, the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) reports that binge drinking, defined as five or more drinks on one or more occasions in the past month, is reported to have occurred in approximately 15% of the survey population from 1990 to 2010. Recent studies indicate that the frequency of binge drinking appears to be rising on college campuses. Chronic drinking—defined as two or more drinks per day or more than 60 drinks per month—is rising. The median in 1990 was 3.2% of the survey population, grew to 5.9% in 2002, and was reported as 5.0% in 2010 (CDC, 2010). A common characteristic of alcohol abusers is denial of a problem. Individuals who abuse alcohol may continue to consume alcohol despite the knowledge that continued consumption poses a significant social and health hazard to themselves.

Research over the past 25 years indicates that with acute ingestion of alcohol, the central nervous system (CNS) depressant effects of alcohol come from release of the major inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and suppression of the major excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, a by-product of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. With long-term chronic ingestion, the reverse occurs: tolerance to alcohol leads to reduced GABAergic activity and higher levels of NMDA activity. There are also inconsistent effects on the serotonin, dopamine, and opioid receptors of the CNS that may also account for some of the acute and chronic effects of alcohol ingestion. Stimulation of opioid and dopamine receptors appears to be related to the alcohol “high,” or the rewarding aspects of drinking alcohol.

Intoxication

Alcohol abuse, or more appropriately ethanol abuse, is commonly called alcohol intoxication. Intoxication is defined as the ingestion of ethanol to the point of clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychological changes (e.g., inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, mood lability, impaired judgment, impaired social or occupational functioning). These changes are accompanied by evidence of slurred speech, incoordination, unsteady gait, nystagmus, impairment in attention or memory, or stupor or coma (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Withdrawal

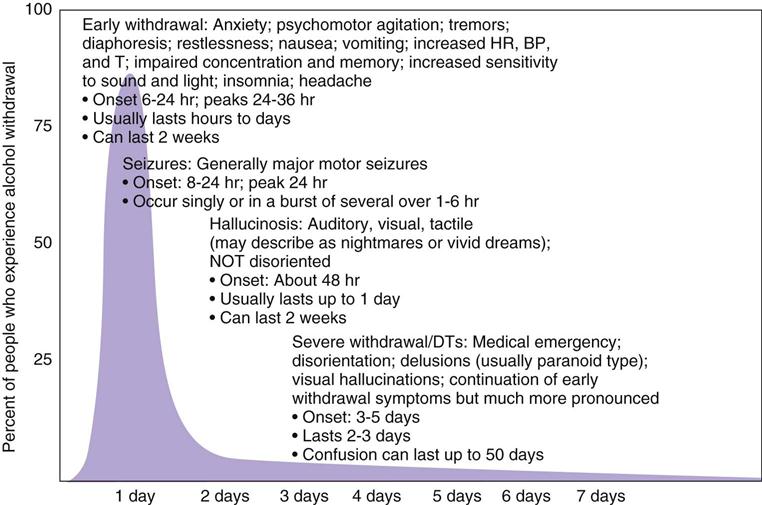

When alcohol is ingested in quantities leading to intoxication, symptoms of overindulgence (e.g., “hangover,” queasy stomach, headache) are common over the next several hours because of direct toxic effects on body cells. If a person frequently drinks to intoxication over long periods (i.e., months to years), a physical dependence (i.e., addiction) develops and a decrease in the blood alcohol level over 4 to 12 hours may cause symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Development of withdrawal symptoms and craving often induces the person to continue to abuse alcohol. (See Figure 49-2 for symptoms and a time sequence of alcohol withdrawal.) The person may no longer get much effect from the alcohol other than its ability to prevent withdrawal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree