Drugs Used to Treat Upper Respiratory Disease

Objectives

1 Describe the function of the respiratory system and discuss the common upper respiratory diseases.

2 Discuss the causes of allergic rhinitis and nasal congestion.

4 Define rhinitis medicamentosa, and describe the patient education needed to prevent it.

Key Terms

rhinitis ( ) (p. 472)

) (p. 472)

sinusitis ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

allergic rhinitis ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

antigen-antibody ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

histamine ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

rhinorrhea ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

decongestants ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

rhinitis medicamentosa ( ) (p. 473)

) (p. 473)

antihistamines ( ) (p. 474)

) (p. 474)

anti-inflammatory agents ( ) (p. 475)

) (p. 475)

Upper Respiratory Tract Anatomy and Physiology

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

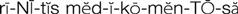

The respiratory system is a series of airways that start with the nose and mouth and end at the alveolar sacs within the lungs. The upper respiratory tract is composed of the nose and its turbinates, the sinuses, the nasopharynx, the pharynx, the tonsils, the eustachian tubes, and the larynx (Figure 30-1). The nose and its structures serve two functions: olfactory (i.e., smell) and respiratory. The olfactory region is located in the upper part of each nostril. It is an area of specialized tissue cells (i.e., olfactory cells) that contain microscopic hairs that react to odors in the air and then stimulate the olfactory cells. The olfactory cells in turn send signals to the brain, which processes the sensation that people perceive as a particular smell.

The respiratory function of the nose is to warm, humidify, and filter the air inhaled to prepare it for the lower respiratory airways. Both nasal passages have folds of skin called turbinates that significantly increase the surface area of the passages and contain massive numbers of blood vessels. The blood circulating through the membranes lining the turbinates warms and humidifies inhaled air. The inhaled air is also filtered of particulate matter. The hairs at the entrance to the nostrils remove large particles, and the turbinates and narrowness of the nasal passages cause turbulence of the airflow passing through with each inhalation. All of the surfaces of the nose are coated with a thin layer of mucus, which is secreted by goblet cells. Because of the turbulence of the airflow, particles are thrown against the walls of the nasal passages and become trapped in the mucosal secretions. The epithelial cells lining the posterior two thirds of the nasal passages contain cilia that sweep the particulate matter back toward the nasopharynx and pharynx. Once in the pharynx, the particulate matter is expectorated or swallowed. The warming, humidification, and filtration processes continue as the air passes into the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles.

The nasal structures are innervated by the autonomic nervous system. Cholinergic stimulation causes vasodilation of the blood vessels lining the nasal mucosa, and sympathetic (primarily alpha-adrenergic) stimulation causes vasoconstriction. The cholinergic fibers also innervate the secretory glands. When stimulated, they produce serous and mucous secretions within the nostrils.

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled cavities in the cranial bones on both sides and behind the nose. There are eight sinuses (four on each side). The purpose of the paranasal sinuses appears to be to act as resonating chambers for the voice and as a means of lightening the bones of the head. The sinuses are lined with the same mucous membranes and ciliated epithelia as those of the upper respiratory tract. The sinuses are connected to the nasal passages by ducts that drain into the nasal cavity from activity of the ciliated cells.

On either side of the oral pharynx is a pharyngeal tonsil, a collection of lymphoid tissue that is called the adenoids when enlarged. The tonsils are located in an area where mucus laden with particulate matter (e.g., virus particles, bacteria) accumulates from the ciliary action of cells in the nasopharynx above. The lymphoid tissue is rich in immunoglobulins, and is thought to play a role in the immunologic defense mechanisms of the upper airway.

Sneezing is a physiologic reflex used by the body to clear the nasal passages of foreign matter. The sneeze reflex is initiated by irritation of the nasal mucosa by foreign particulate matter. It is similar to the cough reflex, which clears the lower respiratory airways of secretions and foreign matter.

Common Upper Respiratory Diseases

Rhinitis is inflammation of the nasal mucous membranes. Signs and symptoms include sneezing, nasal discharge, and nasal congestion. Rhinitis is often subclassified as acute or chronic on the basis of the duration of the signs and symptoms. The most common causes of acute rhinitis are the common cold (viral infection), bacterial infection, presence of a foreign body, and drug-induced congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa). Common causes of chronic rhinitis are allergy, nonallergic perennial rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, and a deviated septum.

The common cold is actually a viral infection of the upper respiratory tissues. When considering the amount of time lost from school and work and the number of health care provider office visits that this condition causes annually, it is probably the single most expensive illness in the United States. Seasons in which viral infections reach near-epidemic proportions are midwinter, spring, and early fall (i.e., a few weeks after school starts). Six different virus families, including 120 to 200 subtypes, cause cold-like symptoms; the most common are the rhinoviruses and coronaviruses. Viruses are spread from person to person by direct contact and sneezing. The earliest symptoms of a cold are a clear, watery nasal discharge and sneezing. Nasal congestion from engorgement of the nasal blood vessels and swelling of nasal turbinates quickly follows. Over the next 48 hours, the discharge becomes cloudy and much more viscous. Other symptoms include coughing, a “scratchy” or mildly sore throat (pharyngitis), and hoarseness (laryngitis). Other symptoms that occur less frequently are headache, malaise, chills, and fever. A few patients may develop a fever up to 100° F (37.8° C). Symptoms should subside within 5 to 7 days.

Complications occasionally develop as a result of the challenge to the body’s immune system initiated by cold viruses. Complications can also arise from thick, tenacious mucus obstructing the sinus ducts or the Eustachian tubes to the middle ears. Bacteria are easily trapped behind these obstructions in the sinuses and ears, resulting in bacterial sinusitis or otitis media (infection of the middle ear). Viral infections are also a common cause of exacerbations of obstructive lung disease and of acute asthmatic attacks in susceptible individuals. If symptoms of the cold do not begin to resolve after several days or if symptoms become worse or additional symptoms appear (e.g., temperature higher than 100° F (37.8° C), earache), a health care provider should be consulted.

Allergic rhinitis is inflammation of the nasal mucosa as a result of an allergic reaction. Patients with allergic rhinitis have had previous exposure to one or more allergens (e.g., pollens, grasses, house dust mites) and have developed antibodies to those allergens. After this exposure, when the person inhales the allergen, an antigen-antibody reaction occurs, causing inflammation and swelling of the nasal passages. One of the major causes of symptoms associated with an allergy is the release of histamine during the antigen-antibody reaction.

Histamine is a compound derived from an amino acid called histidine that is stored in small granules in most body tissues. Its physiologic functions are not completely known, but it is released in response to allergic reactions and tissue damage caused by trauma or infection.

When histamine is released in the area of tissue damage or at the site of an antigen-antibody reaction (e.g., a pollen inhaled into the nose of a patient who is allergic to that specific pollen), it reacts with the histamine-1 (H1) receptors in the area, and the following reactions take place: (1) the arterioles and capillaries in the region dilate, allowing increased blood flow to the area that results in redness; (2) the capillaries become more permeable, resulting in the outward passage of fluid into the extracellular spaces, causing edema (this is manifested by congestion in the mucous membranes and turbinates of the patient’s nose); and (3) nasal, lacrimal, and bronchial secretions are released, resulting in a runny nose (rhinorrhea) and watery eyes (conjunctivitis) noted in patients with allergies. Patients with allergic rhinitis also complain of itching of the palate, ears, and eyes. Most patients with asthma have an allergic component to the disease that triggers acute asthma attacks.

When large amounts of histamine are released (e.g., during a severe allergic reaction), there is extensive arteriolar dilation. Blood pressure drops (hypotension), the skin becomes flushed and edematous, and severe itching (urticaria) develops. Constriction and spasm of the bronchial tubes make respiratory effort more difficult (dyspnea), and copious amounts of pulmonary and gastric secretions are released.

Allergies may be seasonal or perennial. Seasonal allergies occur when a particular allergen is abundant—tree pollen is prevalent from late March to early June; ragweed is abundant from early August until the first hard freeze in October; and grasses pollinate from the middle of May to the middle of July. Weather conditions (e.g., rainfall, humidity, temperature) affect the amount of pollen produced during a particular year but not the actual onset or termination of the specific allergen’s season. It is common for a person to be allergic to more than one allergen simultaneously, so seasonal allergies may overlap or may occur more than once per year. People who have allergies to multiple antigens (e.g., smoke, molds, animal dander, feathers, house dust mites, pollens) have varying degrees of symptoms all year round and are said to have perennial allergies. Allergy symptoms need to be treated, not only for symptomatic relief but also to prevent irreversible changes within the nose, such as thickening of the mucosal epithelium, loss of cilia, loss of smell, recurrent sinusitis and otitis media, growth of connective tissue, and development of nasal or sinus polyps that aggravate rhinitis and secondary infections.

Overuse of topical decongestants may lead to a rebound of nasal secretions known as rhinitis medicamentosa. This secondary congestion is thought to be caused by excessive vasoconstriction of the blood vessels and by direct irritation of the nasal membranes by the solution. When the vasoconstrictor effects wear off, the irritation causes excessive blood flow to the passages, causing swelling and engorgement to reappear; the nose feels stuffier and more congested than it did before treatment. Over the following few weeks, a vicious cycle develops, involving more frequent use of the topical decongestant to relieve nasal passage swelling and obstruction. Rhinitis medicamentosa may develop as early as 3 to 5 days after use of long-acting topical decongestants such as oxymetazoline and xylometazoline, but it usually does not develop until after 2 to 3 weeks of regular use of short-acting topical decongestants such as phenylephrine.

Treatment of Upper Respiratory Diseases

Common Cold

Treatment of the common cold is limited to relieving the symptoms associated with rhinitis and, if present, pharyngitis and laryngitis; reducing the risk of complications; and preventing the spread of viral infection to others. Decongestants are the most effective agent for relieving nasal congestion and rhinorrhea.

The use of antihistamines (H1-receptor antagonists) for symptomatic relief of cold symptoms has been controversial. Studies indicate that preschool-age children do not benefit from the use of antihistamines; however, older children, adolescents, and adults do receive some benefit.

Depending on whether fever, pharyngitis, or cough is present, patients may also benefit from the use of analgesics, antipyretics (see Chapter 20), expectorants, and antitussive agents (see Chapter 31). Laryngitis should be treated by resting the vocal cords as much as possible. Inhaling cool mist vapor several times daily to humidify the larynx may be beneficial, but putting medication into the inhaled vapor is of no value. Lozenges and gargles do nothing to relieve hoarseness, because they do not reach the larynx.

Allergic Rhinitis

The first steps in treating allergic rhinitis are to (1) identify the allergens—usually through skin testing—and (2) avoid exposure, if possible. Unfortunately, it often is not possible to eliminate exposure to many allergens without severe lifestyle restrictions. Medicines must then be used to block the allergic reaction or treat the symptoms. The pharmacologic agents typically used include antihistamines, decongestants, and intranasal corticosteroid anti-inflammatory agents. Saline nasal sprays can be effective in reducing nasal irritation between doses of other pharmacologic agents. If the patient is physically able, vigorous exercise for 15 to 30 minutes once or twice daily increases sympathetic output and induces vascular vasoconstriction.

Mild allergic rhinitis can be well treated by an oral second-generation antihistamine (e.g., loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine) or a nasal corticosteroid alone. Patients who have moderate to severe symptoms of allergic rhinitis with nasal congestion often require both an oral second-generation antihistamine and nasal corticosteroids. Immunotherapy may be required if symptoms are only partially controlled, if high doses of intranasal or oral corticosteroids are required, or if the allergic rhinitis is complicated by asthma or sinusitis.. Therapy should be started before the anticipated appearance of allergens and continue during the time of exposure.

Rhinitis Medicamentosa

The best treatment of rhinitis medicamentosa is prevention. Unfortunately, most patients are not aware of the condition until it becomes a problem. Following the directions for a daily dosage and limiting the duration of therapy to that described on the topical decongestant product are the best ways to avoid the condition.

Several treatment strategies have been successful in treating rhinitis medicamentosa. Regardless of the approach used, the patient must understand what caused the rebound congestion and why it is important to eliminate the problem. One strategy is to withdraw the topical decongestant completely at once. The patient is likely to be congested and uncomfortable for the next week, but use of a saline nasal spray can help moisturize irritated nasal tissues. Nasal steroid solutions can also be used, but they still take several days to reduce inflammation and congestion. Probably the most successful approach, although the longest to complete, is to have the patient work to clear one nostril at a time. Start by reducing the strength and frequency of the decongestant used in the left nostril, while continuing with the normal dosage in the right nostril. Saline or corticosteroid nasal spray can be used every other dose in the left nostril. Eventually, the saline can be used more frequently and the decongestant can be discontinued in the left nostril. Once the patient can breathe normally through the left nostril, the same approach can be started in the right nostril. Frequent follow up with the patient and reinforcement of progress made are important to the success of this treatment.

Drug Therapy for Upper Respiratory Diseases

Actions and Uses

Antihistamines, or H1-receptor antagonists, are the drugs of choice for treating allergic rhinitis. Because they are administered orally and thus distributed systemically, they also reduce the symptoms of nasal itching, sneezing, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, and conjunctival itching. However, antihistamines do not reduce nasal congestion.

Decongestants are alpha-adrenergic stimulants that cause vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa, which significantly reduces nasal congestion. When treating allergic rhinitis, decongestants are often administered in conjunction with antihistamines to reduce nasal congestion and counteract the sedation caused by many antihistamines.

Anti-inflammatory agents administered intranasally are used to treat nasal symptoms resulting from mild to moderate allergic rhinitis. In general, anti-inflammatory agents are not used to treat symptoms associated with a cold, because the symptoms start to resolve before the anti-inflammatory agents can become effective. The anti-inflammatory agents used to treat allergic rhinitis are corticosteroids and cromolyn sodium.

Nursing Implications for Upper Respiratory Diseases

Nursing Implications for Upper Respiratory Diseases

Nasal congestion, allergic rhinitis, and sinusitis are treated with prescription or OTC medicines. The roles of the nurse in the health care provider’s office are to perform the initial assessment of symptoms and then focus on teaching the proper techniques for self-administering and monitoring of the medication therapy. Always review the patient’s history for other diseases currently being treated (e.g., hypertension, glaucoma, asthma, prostatic hyperplasia) that may contraindicate the concurrent use of some upper respiratory medications used as OTC or prescribed treatments.

Assessment

Description of Symptoms

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree