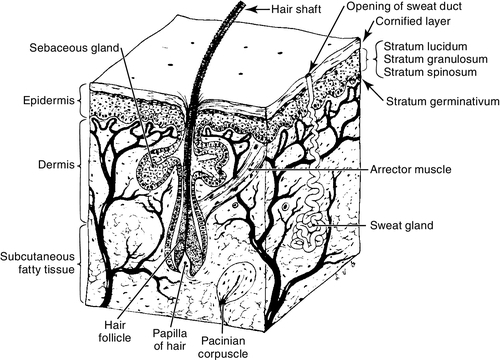

CHAPTER 36 1. Name three functions of the skin. 2. Describe two ways in which the skin of a newborn or preterm infant differs from that of an adult. 3. Identify three factors that affect the appearance of the neonate’s skin. 4. Identify two nursing interventions that provide protection for the preterm infant’s skin. 5. Recognize three common skin lesions that are normal variations in the newborn infant. Describe their appearance and treatment, if any. 6. Describe three common vascular lesions in the neonate, their appearance, and appropriate treatment. 7. Identify two syndromes associated with vascular lesions. 8. Evaluate two pigmented lesions occurring in the newborn infant and list implications associated with each. 9. Name two types of infectious skin lesions and select the appropriate treatment. Careful assessment of the skin is an important element of the neonatal physical examination. The appearance of the skin gives the nurse important clues regarding gestational age, nutritional status, function of organs such as the heart and liver, and the presence of cutaneous or systemic disease. It is important for the clinician to be familiar with normal variances in the skin of the newborn infant as well as those variances that signify disease. Proper care of the neonate’s skin can directly affect mortality and morbidity, especially in the preterm infant. The skin is the first line of defense against infection. Proper skin care can protect the integrity of the skin and prevent breakdown. A. Anatomy of the skin—three main layers (Fig. 36-1). b. Lower layers of epidermis: contain keratin-forming cells that create the outer layer of skin as well as melanocytes, which produce melanin, or pigment. Despite racial differences in pigmentation, the number of melanocytes in a given surface area of skin is the same (Paller and Mancini, 2011; Weston et al., 2007). 2. Dermis: directly under epidermis; 2 to 4 mm thick at birth. The dermis is composed of: b. Blood vessels and nerves that carry sensations of heat, touch, pain, and pressure from the skin to the brain and provide protection against injury, infections, or other invasions. c. Sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair shafts. 3. Subcutaneous layer: fatty tissue functions as insulation, protection of internal organs, and calorie storage. B. Functions of the skin. (2) Process of constant sloughing and replacement of stratum corneum prevents colonization of the skin surface by bacteria and other organisms. b. Chemical/bacterial. (1) Acidic surface of skin (pH 5 to 6) provides defense against bacteria and other microorganisms (Percival et al., 2012). (2) Production of melanin protects against damage from ultraviolet-light radiation. 2. Heat regulation. a. Production and evaporation of sweat. b. Dilation and constriction of blood vessels. c. Insulation of body by subcutaneous fat. 3. Sense perception: heat, touch, pain, and pressure. C. Differences in newborn/preterm skin. 1. Basic structure is same as that of the adult. The epidermis is nearly mature by 34 weeks of gestation (Dyer, 2013). Less mature neonates have less mature skin epidermis and dermis, and minimal subcutaneous fat. 2. Skin adaptation occurs rapidly during the first few weeks after birth. The full-term infant will achieve a stratum corneum that is structurally and functionally equivalent to the adult by approximately 2 weeks of age. The preterm infant will also experience accelerated skin maturity, although it may take as long as 4 to 8 weeks in the extremely preterm neonate (Dyer, 2013; Fluhr et al., 2011; Paller and Mancini, 2011). The acid mantle of the epidermis develops over 5 to 6 weeks, with the pH value decreasing from around 6.0 in the newborn to 5.1, which is comparable to adult levels (Fluhr et al., 2011). 3. The earlier the gestational age, the more thin and gelatinous is the skin, with fewer layers in the stratum corneum and a thinner dermis with fewer elastic fibers. Transepidermal water loss is inversely related to gestational age, and even at 4 weeks of age a 25-weeks-gestation infant has twice the transepidermal water loss as a term infant (Agren et al., 2006; Gilliam and Williams, 2008; Hammarlund and Sedin, 1979). Subcutaneous fat is accumulated predominantly during the third trimester. b. Brown fat, which is important for temperature regulation in the newborn infant, begins to differentiate during the seventh month of gestation (Loomis et al., 2008). 4. Immature skin is thinner and therefore more permeable. a. An infant, especially a preterm infant, quickly absorbs topically applied medications and chemicals (Blumer and Reed, 2011; Loomis et al., 2008, Paller and Mancini, 2011). b. Greater permeability allows for greater insensible water loss in the preterm infant. c. Higher surface area–body weight ratio also allows for greater absorption of chemicals and greater transepidermal water loss. 5. Fewer fibrils connect the dermis and epidermis, and they are more fragile in term and preterm skin than in the skin of an adult. The stratum corneum is thinner in the term and preterm infant. Risk of injury from tape, monitors, and handling is increased, especially in the preterm infant; this type of injury includes removal of the outermost layer of the dermis with removal of tape or electrodes (Ness et al., 2013; Sardesai et al., 2011). 6. Sweat glands are present at birth, but full adult functioning is not present until the second or third year of life. Although present in the preterm infant, sweat glands are immature and function poorly before 36 weeks of gestation (Gilliam and Williams, 2008). a. The newborn infant has limited ability to tolerate excessive heat. b. Vasodilation to increase heat loss can result in hypotension and dehydration caused by increased insensible water loss. 1. Initial bath with water and a mild soap. a. Plain water or mild soaps with a neutral pH should be used for bathing neonates (Lavender et al., 2013). b. Safety of bacteriostatic soaps has not been determined. These products may be too harsh for the neonate’s skin and may negatively affect normal skin colonization (Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses [AWHONN], 2007). c. As soon as the body temperature is stable (> 36.5° C [97.7° F]), it is advisable to bathe the healthy term infant to decrease the caregiver’s risk of exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Standard Precautions, including the use of gloves, should be adhered to when handling the infant who has not been bathed after delivery and during any invasive procedure in which the caregiver may be exposed to body fluids (Dyer, 2013). 2. Parents may prefer to give the first bath themselves. 3. Vernix caseosa contains fats and proteins that protect the skin from the amniotic fluid and bacteria in utero, and is thought to aid in skin maturation after birth. Vernix insulates the stratum corneum and should not be removed during the initial bath (Dyer, 2013; Visscher et al., 2011). 4. When possible, avoid puncturing the skin of babies with suspected maternal infections. 5. Routine use of emollients is not recommended in the term infant. Creams and emollients that contain perfumes are drying and may irritate the infant’s skin. Products that change the pH of the skin decrease the bacteriostatic properties. If cracking or fissures develop in the skin, a nonperfumed emollient such as white petrolatum may be used (AWHONN, 2007; Ness et al., 2013). B. Preterm infant. 1. Keep skin clean with water. Mild, nonalkaline soap may be used on soiled areas as needed; otherwise plain water is acceptable. Preterm infants should be bathed infrequently during the first 2 months of life to avoid excessive drying of the skin and to avoid overstimulation, stress, and fatigue (AWHONN, 2007). 2. Handle infant gently and minimally to avoid trauma. 3. Minimize use of tape and other adhesives as much as possible. Use care when removing tape to avoid stripping the epidermis (AWHONN, 2007; Sardesai et al., 2011). b. Gelled adhesives and pectin-based barriers are good alternatives to tape, as removal causes less trauma to the skin (Ness et al., 2013). c. Pectin or hydrocolloid layers applied before adhesives may protect the skin from damage when endotracheal tubes or catheters are secured (AWHONN, 2007). d. Benzoin and other adhesive bonding agents form a strong bond between the adhesive and the epidermis, increasing the risk of stripping the epidermis when the adhesive is removed. Use of these agents with preterm infants should be avoided. 4. Increased permeability of the skin allows absorption of some medications and products such as alcohol and povidone–iodine (Pinsker et al., 2013). When these substances are used for an invasive procedure, it is recommended that they be removed completely with water as soon as possible to prevent absorption or chemical burns. 5. The skin should be disinfected before any invasive procedure. Although chlorhexidine gluconate has been shown to be more effective than other agents in reducing skin colonization, it has not been approved for use in infants less than 2 months of age. Chlorhexidine gluconate is available in single-use applicators that contain 70% alcohol but may be drying to the neonate’s skin or cause burning or other injury (AWHONN, 2007; Garland et al., 2009; Stevens and Schulman, 2012). 6. Emollient creams that are free of preservatives and perfumes may be of benefit to the preterm infant as they decrease transepidermal water loss and skin breakdown when cracking, excessive dryness, or fissures are present (AWHONN, 2007; Lund and Kuller, 2007). Humidity at levels of 70% to 90% during the first week after birth reduces insensible water loss and evaporative heat loss in extremely low birth weight infants. Humidity should be gradually decreased to 50% after the first week. Transepidermal water loss in extremely low birth weight infants decreases after the first week after birth. Decreasing humidity to around 50% may improve skin barrier maturation (Agren et al., 2006). 7. Transparent adhesive dressings can be used over wounds and abrasions and to secure intravenous (IV) catheters and central lines (Lund and Kuller, 2007). C. Umbilical cord care. 1. Sterile cutting of cord at delivery, rapid drying of umbilical cord, and keeping cord clean is the most effective way to prevent umbilical infections. The use of antimicrobial creams or ointments has not been shown to be more effective in preventing infection than keeping the cord clean and dry (Ness et al., 2013). 2. Some studies have suggested that chlorhexidine may be of benefit in cord care, particularly in circumstances in which infection risk is increased, although cord separation time may be lengthened (Mullany et al., 2013). 3. Bathing does not increase the rate of omphalitis or cause a delay in cord separation. 4. It is normal for the cord to appear slightly mucky, with small amounts of cloudy, mucus-like material at the junction of the cord and abdominal skin. 5. Omphalitis is characterized by serosanguineous drainage, inflammation of the surrounding tissues, and a foul odor. Poor feeding, lethargy, and fever may also be associated. Suspected omphalitis should be treated immediately with IV antibiotics. A. Factors affecting the appearance of the skin. 2. Postnatal age. 3. Nutritional status and hydration. 4. Racial origin. 5. Type and amount of available light. 6. Hemoglobin and bilirubin levels. 7. Environmental temperatures. 8. Oxygenation status. B. Definitions used to describe skin lesions (Paller and Mancini, 2011; Weston et al., 2007). 2. Papule: a solid, elevated, palpable lesion, with distinct borders less than 1 cm in diameter. 3. Plaque: a solid, elevated, palpable lesion, with distinct borders, greater than 1 cm in size. 4. Nodule: a solid lesion, elevated with depth, up to 2 cm in size. 5. Tumor: a solid lesion, elevated with depth, greater than 2 cm in size. 6. Vesicle: an elevated lesion or blister filled with serous fluid and less than 1 cm in diameter. 7. Bulla: a fluid-filled lesion larger than 1 cm. 8. Pustule: a vesicle filled with cloudy or purulent fluid. 9. Petechiae: subepidermal hemorrhages, pinpoint in size. They do not blanch with pressure. 10. Ecchymosis: a large area of subepidermal hemorrhage. 11. Wheal: area of edema in the upper dermis, creating a palpable, slightly raised lesion. 12. Ulcer: erosion of skin with damage of the epidermis into the dermis. Will leave a scar after healing. A. Normal variations in newborn skin. a. Bluish mottling or marbling effect of the skin. b. Physiologic response to chilling caused by dilation of capillaries and venules. c. Disappears when infant is rewarmed. d. May be a sign of stress or overstimulation in newborn infant. e. Common in infants with trisomies 18 and 21. f. If condition persists in infants 6 months of age or older, it may be a symptom of hypothyroidism or a vascular abnormality such as cutis marmorata telangiectasia (Paller and Mancini, 2011). 2. Harlequin color change (Fig. 36-2). b. Caused by immaturity or temporary disturbance of the autonomic regulation of the cutaneous vessels. It is more common in preterm neonates. 3. Erythema toxicum (newborn rash) (Fig. 36-3). a. Small white or yellow pustules surrounded by an erythematous base (erythematous base is caused by histamine release) (Hussain et al., 2013; Lucky, 2008). b. Benign, found in up to 70% of newborn infants (Hussain et al., 2013). c. Seen in neonates and infants up to 3 months of age. d. Lesions come and go on various sites of face, trunk, and limbs, although they are never seen on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. e. Cause unknown, but condition may be exacerbated by handling or by chafing from linen. f. Differential diagnosis: may resemble a staphylococcal infection. Diagnosis can be confirmed by smear of aspirated pustule showing numerous eosinophils. g. No treatment is necessary. Lotions or creams may exacerbate condition.

Neonatal Dermatology

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE SKIN

CARE OF THE NEWBORN INFANT’S SKIN

ASSESSMENT OF THE NEWBORN INFANT’S SKIN

COMMON SKIN LESIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

36: Neonatal Dermatology

FIGURE 36-1 ■ Several layers and structures of human skin. (From Francis, C.C. and Martin, A.H.: Introduction to human anatomy [7th ed.]. St. Louis, 1975, Mosby.)

FIGURE 36-2 ■ Harlequin color change. (Courtesy Jane Deacon, RNC, M.S., NNP, The Children’s Hospital, Denver, Colo.)

FIGURE 36-3 ■ Erythema toxicum. (Courtesy Jacinto Hernandez, M.D., The Children’s Hospital, Denver, Colo.)